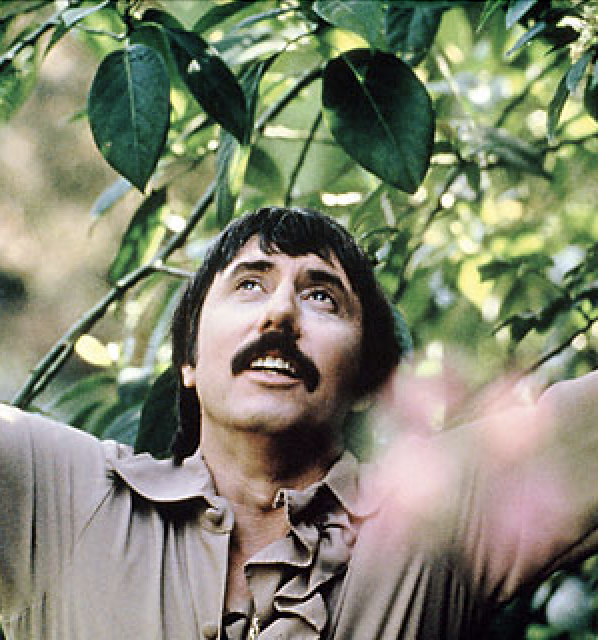

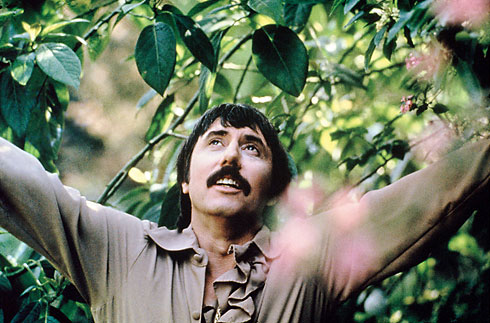

For half a century, Lee Hazlewood has been skillfully subverting the pop-music world. As a producer, songwriter and musical guru, he’s given birth to a wide-ranging and remarkable body of work. He’s one of the few figures who can lay claim to status as both a popular hitmaker and a cult icon.

In the ’50s, Hazlewood’s studio inventions gave an otherworldly quality to early rock ’n’ roll; in the ’60s, he played Svengali to a young Nancy Sinatra, penetrating the charts with some of the oddest and most affecting productions ever. After releasing a string of moody MOR albums as a solo artist, Hazlewood faded from sight, moving to Sweden in the ’70s. Following two decades of self-imposed professional exile, he re-emerged in the mid-’90s at the insistence of a new generation of fans: celebrities and musicians—such as Nick Cave, Courtney Love and Sonic Youth’s Steve Shelley—who clamored to hear him again.

A professional renaissance followed, including a steady stream of reissues, tribute discs and tours. The last couple years have found Hazlewood in poor health, battling cancer and various complications. Still, he’s managed to complete what he calls his final album, Cake Or Death (Ever). Taking its title from an Eddie Izzard stand-up bit, the album features a batch of newly penned Hazlewood compositions and revamped versions of some catalog classics. Recorded in Stockholm, Paris, Nashville, Phoenix and Los Angeles, Cake Or Death is a mixture of high camp, low comedy and genuinely moving moments, such as album-closing valediction “T.O.M. (The Old Man).”

Speaking to MAGNET, the 77-year-old Hazlewood considered his latest LP and looked back on his career and a life well lived.

How are you feeling these days?

Fifty-fifty. Some days are good, some days are bad. But I’ve had more good days than bad days lately.

You spent a good while in the studio working on Cake Or Death. Did you enjoy it? Because it always seemed like you didn’t care to be in the studio much anymore.

Well, I hate the studio. I’ve spent so much time in studios, my god. In the old days, I used to say I spent so much time in the studio producing that my children called me “Uncle Daddy”; it almost was like that. That’s about when I started taking my long two- or three-year vacations from the business. So, yeah, there was a lot of pain doing this album stuck in a studio. I’d rather be out somewhere having Scotch or something. And now I can’t even drink Scotch! [Laughs]

Your longtime friend Al Casey, who was one of the contributors on this record, recently passed away.

Yeah, we worked together since Al was 16, and I don’t think anybody—including Al—knew how great he was. He played with everybody: Sinatra, Elvis, the Beach Boys, you name it. He recorded with half the people in the world, and it impressed him not at all.

When you started out in the late ’50s in Phoenix, you were working in some pretty crude studios.

The first hit I had was “The Fool” [sung by] Sanford Clark. It was the third thing I’d ever done and the first top-10 record I ever had. Once we had “The Fool” and got some money, we built the studio out, and what we had been using for the studio became the bathroom. The place where I cut “The Fool” later became a men’s toilet. That’ll give you an idea of how crude the place we were working in was. [Laughs]

But at the same time, it seemed like there was more room for invention and creativity in those days, because things were so primitive.

Well, you see, in the late ’50s, the major labels didn’t know anything. They had A&R men who were as old as I am now. Meanwhile, we were just kids in there trying everything we could and making what we liked. We were getting better results than what the majors were coming up with.

Your first couple solo albums, (1963’s) Trouble Is A Lonesome Town and (1965’s) The N.S.V.I.P.’s, were narratives about odd, small-town folks with names like Emery Zickafuce Brown, Sleepy Giloreeth and Windfield Bloodsaw. That was all based on your experiences growing up in Mannford, Okla., right?

I grew up there the first few years, then I’d go up and visit my aunt and my grandfather who had a ranch just outside of town. I enjoyed those people, but I knew they were strange even when I was six or seven years old. Their names were odd, and so were the people. I liked them, but they were not like the other people I’d met in larger cities. I based a lot of those early songs on them, but some of the stories I left out. They were so strange that no one would believe them. I mean, who would believe that in a town of 365 people, two guys went off to World War I and one came back with his left foot gone and one came back with his right foot gone and once a year they’d get on a bus and ride into Tulsa and buy a pair of shoes? [Laughs] This town was just loaded with characters like that. Shakespeare never had characters that good.

Cake Or Death has a few older songs that you revisit, but a lot of it is new stuff.

I wrote about 40 songs for it and threw a bunch away. Speaking of Al Casey again real quick: Whenever people used to ask him, “What do you think about Lee and his songs?” Al would say, “He’s an OK songwriter. The best songs he ever wrote, he threw in the wastepaper basket.” I’m not sure that he wasn’t right.

You do a new version of “These Boots Are Made For Walkin’” on the album.

Well, the version on this record uses my original melody for it. When I wrote it back in ’63, it only had two verses to it. It was kinda my little party song. My friends down in Texas—especially lady friends of mine—would always say, “How come you don’t write a love song?” So I said, “Well, I’m gonna write a love song.” When I wrote “Boots,” all the ladies got mad. In that part of Texas, the word “messin’” means “fucking,” it means nothing else other than that. [Laughs] Later, we gave it a little melody change for Nancy, and she just completely fell in love with it. But I told her she couldn’t do this song and explained why. She said, “I’m from New Jersey, I’ve never heard of messin’.” I called around some of my disc-jockey friends to see if they thought it was too risqué, and they said no. So then I wrote a third verse for it, she cut the song, and it became a big hit. But it needed Nancy rather than me to become a hit. Whenever I sang it at home in Texas, it got me in trouble with the ladies.

There’s a great male/female duet on Cake Or Death: a cover of Dave Loggins’ 1974 FM hit “Please Come To Boston.”

I did it with Ann Kristin Hedmark, who’s a great jazz singer from Sweden. I’ve got no business singing with her. Somebody asked her, “Why do you sing with Lee?” And she goes, “Because I think Lee is funny.” That’s probably as good a reason as any to sing with me.

Cake Or Death is your first album of largely new material in years. Why so long?

Once I got “rediscovered,” as they say, back in ’95 or so, I started working here and there just sitting on a stage being as dumb as I could be and telling little stories and singing my songs, mostly in Europe. People seemed to like that, and I spent a lot of time playing those kinds of shows and had a lot of fun. And it paid well; that helps, too. But it kept me from writing all that much, until the last couple years.

As far as your comeback goes, it really caught you by surprise, didn’t it?

I started hearing about musicians who really liked my music: Beck and folks like that. I’m talking about people three generations away from me. But I think musicians have always liked me. One time I was doing a show—probably for a couple thousand people—and I asked, “Is anybody in this place in a band or a musician?” Well, about 95 percent of the people’s hands went up.

The younger audiences have been coming to hear you do the obscure songs, not the hits, right?

Right. During another show, I did a really obscure song, and they loved it to pieces. I said, “Where in the hell did you people hear this song?” And I pointed at this guy down front, and he said, “Oh, my grandma had the record.” I said, “Well, from now on, it’s grandma P.R. for me.” I guess my records did just lie around, and the kids—or the grandkids—eventually listened to them and liked them. That was the biggest surprise of all. I wrote those songs for me; they weren’t necessarily meant to make money or have any lasting value. But it does make for a nice catalog. I’ve got something like “Boots,” which is a multi-million-dollar song that’s had a life of its own. Then I’ve got all the hits in the middle—“Houston” and stuff like that—and then there are about 80, 90, 100 obscure songs that the kids love. Somewhere in there is not a bad living.

So, after 50 years and dozens of solo records, you’re billing this as your last album ever. Or is it just your last album for a while?

Well, it may be a long, long while. Maybe for eternity. Who in the hell knows? [Laughs]

—Bob Mehr

Hazlewood passed away Aug. 4, 2007.