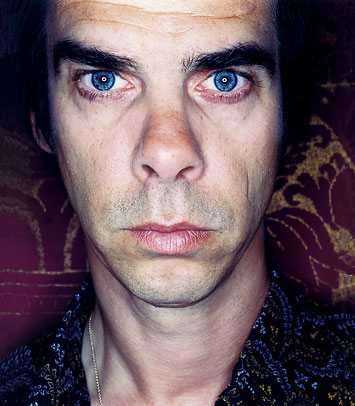

Dating back to his days fronting Australian post-punk legends the Birthday Party, Nick Cave has always told it like it is. In the wake of their 1984 implosion, Cave has pumped out more than a dozen studio albums, a live set, a triple-disc rarities collection and, most recently, a CD/DVD package (concert/video set The Abattoir Blues Tour) with trusty band the Bad Seeds, essaying temptation, redemption and everything in between. The London-based Cave even ventured into screenwriting, penning the script for last year’s acclaimed Western The Proposition. But it’s the struggle to rise above the ugliness of modern life that preoccupies Cave on the debut from Grinderman, which finds him surrounded by Bad Seeds Warren Ellis, Martyn P. Casey and Jim Sclavunos. Grinderman’s self-titled album (on Anti-) is as noisy and raw as anything Cave has done, with provocative songs such as “No Pussy Blues,” “Love Bomb” and “Electric Alice” demonstrating he’s lost none of his lyrical or musical edge. The always stylish Cave, who turns 50 in September, greets MAGNET in a New York City hotel suite overlooking the former World Trade Center site. His once-jet-black hair is now graying and thin, but it’s still combed high atop his head. Over several cups of English Breakfast tea and three hand-rolled cigarettes, Cave discusses the inspiration for his newest project, the joys of rocking out on guitar and the horror of his kids taking an interest in his music.

What’s the key distinction between the Grinderman record and a Bad Seeds record? You could have put the new album out under your own name.

I could have put it out under my own name, although it wouldn’t have felt accurate. I put things out under my own name if I’ve written all the songs. To me, that’s what this whole thing is about: me writing songs. The Bad Seeds are the guys who play my songs. But with Grinderman, the songs were written together. It wouldn’t have seemed accurate to call it a Nick Cave record.

Were these songs written in the studio?

Well, the way we did this record was, I had a notebook like this [grabs a notebook off the floor] with a few titles, but no songs or anything like that. We went into the studio for five days, basically with nothing. We sat together for five days straight and played. We jammed, getting there reasonably early and going half the night. We recorded 50 hours or something of music that we then had to troll through and find stuff we felt defined or came close to our idea about what Grinderman should be. These became springboards for me to go and write lyrics. Some of the lyrics were pretty much there from ad-libbing the stuff. “No Pussy Blues” is pretty much like that. Some I worked a lot on. A lot of thought went into these lyrics. I’m really proud of these lyrics, even though some of them are very simple. I just think they sit together as a group of songs really well, lyrically. A lot of thought went into what we wanted the Grinderman sound to be.

To your ears, what’s the Grinderman sound?

I guess it’s something that’s raw, immediate, catchy and short. Short is very important. The songs are really short, and the album is really short (36 minutes).

Grinderman finds you playing guitar for the first time in ages. Was that fun?

Fuck, yeah. Absolutely. It was like, “Hey ma, I’m playing the guitar!”

Is it a coincidence the Grinderman LP follows (2004 double-disc) Abattoir Blues/The Lyre Of Orpheus?

No. It’s not a coincidence. I like the Abattoir Blues record a lot, but the Grinderman record is its exact opposite in a way.

I think every guy feels the “No Pussy Blues” at one time or another. It’s a simple idea, but one you don’t always share with another person.

I know what you mean. We put it up on MySpace, which was the first time we’ve ever done anything like that, and there was this fucking blizzard of male voices coming back saying, “Tell me about it.” Men, and women as well, were responding to that song in a very personal way.

Just because you’re using that word doesn’t mean women don’t feel that way, too.

Yeah. But I just couldn’t bring myself to write a song called “No Dick Blues.” Maybe on the next record.

The subject matter of that song symbolizes the Grinderman album as a whole. The music matches what’s coming through in the lyrics.

There’s a dark element to the lyrics, and the music as well, but for me, the thing about this music is that it’s incredibly uplifting. I find myself actually playing it, which I never do with Bad Seeds stuff. Not that I’m not proud of the Bad Seeds stuff. I just feel totally responsible for it. With Grinderman, I feel I’m in some role other than the frontman. There’s a shared responsibility for this record, so I can look at it a little more objectively. We had a really good time making this record, and it feels like that to me.

Besides the five days of recording, how much more time did you spend on Grinderman?

It took six or seven days to record. But that’s not unique. We always record quickly with the Bad Seeds. We made Abattoir Blues in 10 days. We try to record three songs a day. It’s not like we set ourselves a short time to do it; we just did it in the amount of time we needed to do it. Since (2003’s) Nocturama, we’ve been playing just straight live with very little overdubs. The overdubs take up all the time. Nick Launay is the producer, and he’s fucking fast. He’s just able to record you how you sound, which is all we want.

Were you involved in putting together (2005 collection) B-Sides & Rarities?

No, no. That was (Bad Seeds member) Mick Harvey’s pet project. He put an enormous amount of work into hunting down all those different recordings. That’s a great record. That was something that arrived on my doorstep pretty much complete. I couldn’t even remember doing some of those songs. A lot of the stuff we record, we never play it back. I was in awe of Mick. Maybe he just didn’t totally blow his brains out in the ‘80s and the ‘90s to be able to remember everything. From my point of view, it’s probably the most enjoyable Bad Seeds record.

There’s been such a rash of rock reunions in the past few years; everybody from the Pixies to Dinosaur Jr to Crowded House. Have you been offered any money to do Birthday Party stuff?

No. Nobody has mentioned it, and we would never do that. I mean, (bassist) Tracy Pew is dead, and he was the engine. As far as I’m concerned, he was what the Birthday Party was all about. I’d never have any interest in doing that. Something like Crowded House, you could be 158 and play a concert, and it would still be much the same. But the Birthday Party came out of a particular time. We were young. It’s young man’s stuff.

It seems like it took quite a while to bring The Proposition to the big screen.

Well, John Hillcoat, the director, had been trying to do this Australian Western for 12 years. I’ve known him for years. He showed me a script, and I told him it wasn’t any good. Out of complete frustration with the whole exercise, he said, “Why don’t you write it?” So I did. I wrote it very quickly, and it got funded immediately. They took it to the U.K. Film Council, which gave them half the money. For the next two years, I sat and watched this unbelievably difficult process of trying to get a film off the ground. You’ve got the actors, then suddenly you don’t have the actors. You’ve got the money, then you don’t have the money. John, to his credit, stuck in there and managed to get the whole thing made. Then, my next involvement was working with the actors on location in Winton (in Queensland, Central Australia) for a week before they started shooting. That was one of the best times I’ve ever had. I had written a pile of words and forgotten about it. But then you saw these great actors (including Guy Pearce, Ray Winstone, Emily Watson and John Hurt) saying these words and making some sense out of them. It was really exciting.

You have two teenagers. Are they getting to the point where they can appreciate your music? Do they listen to it?

Well, they’re both very different kids. One lives in London, one lives in Australia. One I have a lot to do with; the one in Australia, I don’t see that much. Luke, who lives in London, really likes the Grinderman record. But, you know, they don’t sit around playing my music. I’d be deeply disturbed if they did.

—Jonathan Cohen