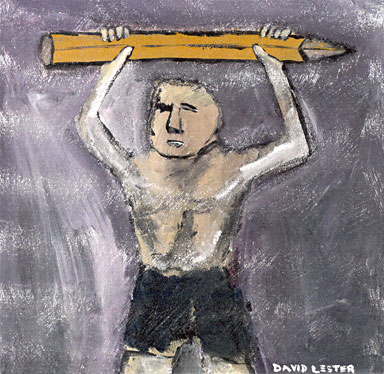

Every Saturday, we’ll be posting a new illustration by David Lester. The Mecca Normal guitarist is visually documenting people, places and events from his band’s 25-year run, with text by vocalist Jean Smith.

Every Saturday, we’ll be posting a new illustration by David Lester. The Mecca Normal guitarist is visually documenting people, places and events from his band’s 25-year run, with text by vocalist Jean Smith.

On the weekend, I went across town to Zulu Records to see political singer/ songwriter Billy Bragg. A free, rainy afternoon in-store. The place was packed.

Dave found out about Billy Bragg in 1985 reading the U.K.’s NME. We had been doing Mecca Normal for a year or so, unaware that Bragg was doing a voice-and-abrasive-guitar thing with political lyrics—this was unusual in those days, between the wars, and for many years Mecca Normal was compared to Billy Bragg in reviews and articles.

In 1986, just after we released our first LP, we went to play in Montreal. We did an interview at CBC Radio (Canada’s national radio network), where we heard that Billy Bragg was part of the Red Wedge in the U.K.: socialist musicians on tour to encourage people to vote for the Labour Party in the U.K.’s 1987 elections, in order to oust the Conservative Party from power. We were inspired by this idea—musicians and poets working together based on similar political beliefs. We formed the Black Wedge that night, there in the basement of the CBC, and toured the U.S., Canada and the U.K. in the following years to illuminate our underground and anti-authoritarian ideas.

At the record store, 51-year-old Billy looked and sounded great—he did about a half dozen songs and turned the chorus of his most famous single, “A New England,” into a sing-along. “I don’t want to change the world/I’m not looking for a new England/I’m just looking for another girl.” From my vantage point, beyond Bragg, several young women sang with delight, but I wondered if the protagonist’s perspective—the guy in the song—was perhaps lost on them, when, in this era, the idea of being able to change the world has been relegated to unrealistic, while the concept of participating in a re-structuring of society has been set aside for immediate comforts. “I don’t want to change the world/I’m not looking for a new England/I’m living with my folks, looking for a cell-phone plan.”

If it’s possible to detect the difference between lower case and capital letters in aural communication, I got the impression people were singing “I’m not looking for New England”: the region north of New York state or the white clam chowder as opposed to the Manhattan red. A place on a map and a bowl of soup are easy, tactile associations; a new England is a more complex prospect to grapple with. Please pass the Rand McNally’s and the Tabasco.

Or maybe it’s that thing that happens when the sound of a song becomes synonymous with its purpose. Lyrics turn into agreeable noises to be chanted without connecting them to the words—their actual, undeniable and important meaning. Seems to me that the song’s purpose was to foist an average youth, circa 1983, into our awareness, to expose a vignette of apathy within the human condition—not to celebrate the guy’s decision to opt out in favor of finding a new girlfriend.

I guess the young women were enthralled in the moment, part of this rendition and probably their views click with Bragg’s, so I’ll focus on my experience, which definitely included a wave of nostalgia, not for the days of overtly political songs, but simply for those days, that time—the thrill of seeing Billy Bragg at the Town Pump in 1986 or so, feeling hopeful and encouraged, part of something.

I didn’t sing along at the record store, but I noticed that I was one hell of a lot closer to the I-can’t-change-the-world-clam-chowder interpretation than I felt comfortable with. My conclusion is that we need new political songs to add to the ones that may become diluted by becoming popular. The friendlification factor has a way of putting intention and meaning on the back burner.

In an article online, Bragg explains the song “I Keep The Faith” from his 2008 album, Mr. Love And Justice: “In it I talk about the faith I have in the ability of the audience to change the world,” says Bragg. “I recognize that my role is to inspire them. But really, the important thing is what happens when I step down from the stage—empowering the audience to make progressive change in the world. We all feel cynicism from time to time. But when you encourage people to overcome that, telling them you have faith in their ability, it’s a powerful message.”