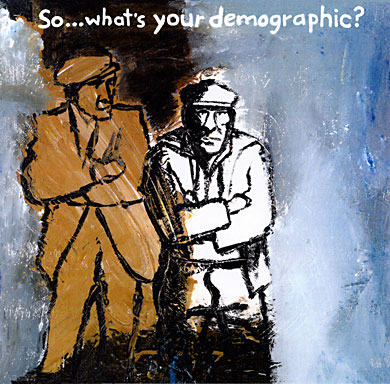

Every Saturday, we’ll be posting a new illustration by David Lester. The Mecca Normal guitarist is visually documenting people, places and events from his band’s 25-year run, with text by vocalist Jean Smith.

Every Saturday, we’ll be posting a new illustration by David Lester. The Mecca Normal guitarist is visually documenting people, places and events from his band’s 25-year run, with text by vocalist Jean Smith.

Winter, 2007. I am on my way to work, catching the 7 a.m. bus to West Vancouver, Canada’s wealthiest neighborhood. It is dark and cold out. I walk past a guy under a bunch of blankets sleeping on the sidewalk. A skinny guy holding a black cross asks me for money.

“No, sorry,” I say and walk part way down the block to wait for my bus. I look back and the guy is shivering, talking sweetly to himself, twisting the cross delicately in his long fingers. He has long dirty hair and a grey sweat suit on, no coat. He regards the item in his hands in such a way that it seems like it isn’t a cross to him. He’s twirling it, inspecting it. I look down and see one shoeless foot twitching in a thin black sock. I decide to go and talk to him. I walk toward him even though something in me is saying, “Don’t, don’t talk, don’t get involved.”

“Do you know where your other shoe is?” I ask.

“Oh,” he says, looking down. “No, I don’t know where it is.”

“I was hoping it was right around here somewhere,” I say.

He looks around, but there is no shoe. I sit down on an empty bench, and he sits beside me.

“Are people being generous with their spare change this morning?” I ask.

“No.”

“Where did you sleep last night?”

“In a doorway.”

“Isn’t there a shelter or some place you can go to?”

“Where?” he asks excitedly, as if I can help him.

“I don’t know. Downtown Eastside?”

He says nothing and twirls the black metal thing.

“Is that a cross? Like, a religious cross?”

“I don’t know,” he says. “I just found it. What is it?”

“Some people might think it’s a cross. It might work to your advantage.”

“How do you mean?” he asks, holding it up to see it at arm’s length.

“Well, I don’t believe in god, but maybe some religious people will give you money if you’re holding that.”

“Really?”

“Maybe,” I say, starting to feel like do-gooder lady giving the guy advice. “How long have you been living on the street?”

“Six years.”

“Wow. How old are you?”

“Twenty-six,” he says and then, turning cheerfully to me, he asks, “How old are you?”

“Forty-eight.”

“Wow, you could be my mother. Do you have any sons?”

“No, I don’t have any kids. I’m a musician. I never wanted to have kids.”

“I could be your son,” he says hopefully. He extends his hand. “My name is Dennis.”

We shake and I think about his hand—when was it last washed, where has it been, what diseases does he have? I put my hand back in my pocket thinking, “Must wash hand when I get to work.”

“Do you play music?” I ask.

“Sometimes I play the piano. There’s a piano store in the next block. We could go there—you can sit in my lap, and I can play piano.”

“Not the worst idea, but they won’t be open and I have to go to work.” I open my packsack. “Let see if I have any change.” I find $2.60 and give it to him.

“Thanks,” he says.

“You’re a very charming guy Dennis and you have a wonderful smile,” I say, hoping to make him feel good, wondering if that might help him at all. “Can you get some food around here?” I ask.

“I might go to the safe-injection site.”

“They have food there?”

“Yes.”

“Do you have a plan for how to survive the winter?”

“I may go back to Winnipeg.”

“Winnipeg?” I say, thinking Winnipeg is about 12,000 times colder than here. I look past Dennis, down the dark street to see if my bus is coming. “Do you have friends there, a place to stay?”

“Not really. I might get some food, get high a couple more times and commit suicide,” he says, hands busy with the cross. “It’s too cold on this planet and I’m hungry all the time.”

“I hope you don’t kill yourself, Dennis. I hope something good happens to you soon,” I say, thinking about my warm clothes: the pink flowery Chinese sweater, down vest, rain jacket. I think about giving him the pink sweater, but he’d probably get the snot beat out of him if he went around wearing it. I need the down vest. I like my rain jacket. My bus pulls in. I stand up. Dennis stands up. “Will you take me for coffee?” he asks.

“I can’t,” I say. “I have to go to work.”

He takes a few dainty hopping steps towards me, saying, “Will you help me get on the bus to warm up?”

“It goes to Horseshoe Bay. You don’t want to go to Horseshoe Bay,” I say, moving to the bus stop. He really shouldn’t go to Horseshoe Bay. I don’t think I could recommend he go into West Vancouver with one shoe, matted hair and a filthy grey sweat-suit.

“Where’s that? Where’s Horseshoe Bay,” he asks, following after me.

“It’s where the ferries are,” I say, wondering if he thinks I mean fairies. “You can catch a city bus on Howe Street,” I say, pointing in the opposite direction. Pointing away from me, moving away from him, catching my bus, going to work in West Vancouver, Canada’s wealthiest neighborhood.

Dennis, shivering, one shoe, thinking about suicide because it’s too cold on this planet and he’s hungry all the time, goes back to the corner where I first saw him. The bus pulls out and moves past him.

I look out the window and cry without making a sound. I have cried on the bus before, for one reason or another, usually self-pity. It is starting to get light. I love to look out the window on the way through Stanley Park, but this morning the trees loom most sorrowfully. Dark and lonely silhouettes.