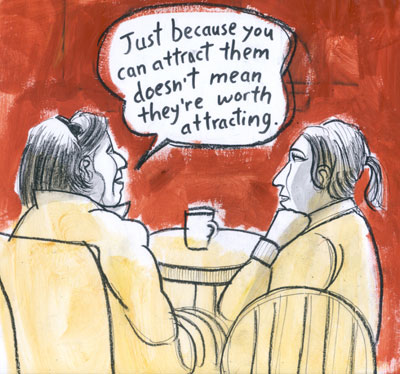

Every Saturday, we’ll be posting a new illustration by David Lester. The Mecca Normal guitarist is visually documenting people, places and events from his band’s 28-year run, with text by vocalist Jean Smith.

Every Saturday, we’ll be posting a new illustration by David Lester. The Mecca Normal guitarist is visually documenting people, places and events from his band’s 28-year run, with text by vocalist Jean Smith.

Nadine flipped the book open to a portrait so loose, she had to double-check that it was Diebenkorn. The head and part of the torso, more Matisse than what Diebenkorn typically conveyed to Nadine. The blue-gray smear of background, the ground, raw board, no attention to hiding what it was. Paint on board. A quick expression of anatomy. A human head. The body, adroit, a shape to make the gray worthy, the pinky-orange dropped into the blue of the gray. It was more about the gray than the face, the head or god forbid, anything going on in the head. The weird gray eyes, like holes bored straight through the head to see the gray behind. A slab of odd nose and—whereas her mother had told Nadine that the most important line in a portrait was between the lips, because the expression was there—the mouth on this head was pronounced by laying down two strokes of paint, very nearly the same color, allowing the expression to be where those two tones met. There was no other line. The nose was a bright protrusion, made very nearly vulgar by bringing the shadow from around the face, the contour field that gradually increases upward to form the nose, in this case on the right side of the head, this shadow was simply brought around and used to cut away nostrils. Indelicately, but most appropriately, since it was the gray of the shadow—on the face and behind the head—that breathed life into the painting as a whole, for Nadine.

The blue-gray of smoke before smoking was going to kill you. The gray-blue of the background, selected to push the orange out. The body that never quite seemed to be content within Diebenkorn’s energetic landscapes, roomscapes. His authoritative aerial sensibility mapping out what had become of us. All cut up and disseminated across the land. The cul de sacs and infrastructural nuances—roads, tabletops, windows, Knife In A Glass—that he constructed roundly, rendering what was hard and ungainly, to obfuscation. Steel wool taken to the image-maker’s lens. A vanishing luminosity, fractured into a well-scoured blur, of what was to quickly crumble into a ghettoized stench, but before it started rotting from within, Diebenkorn obscured it for us, so that it would hurt a little less when the world would, farther along, go all dark and cold. He painted new with a foretelling that this would be the last round of new that we could celebrate, that this new would be coming back around, soon enough, as a legacy that couldn’t be taken back.