In 2006, Quentin Stoltzfus was forced to retire Mazarin, the dreamy, strummy Philadelphia-based project he debuted in 1999, due to threats from a litigious Long Island classic-rock band of the same name. If not for that, the new Light Heat album would be a Mazarin album, and could have come out years ago. The catalyst for Light Heat’s debut came from Stoltzfus’ friends and former tourmates the Walkmen. That band, minus singer Hamilton Leithauser, backs Stoltzfus on the LP, although Light Heat itself, like Mazarin, is essentially Stoltzfus and whomever he plays with. Stoltzfus will be guest editing magnetmagazine.com all week. Read our new feature on Light Heat.

In 2006, Quentin Stoltzfus was forced to retire Mazarin, the dreamy, strummy Philadelphia-based project he debuted in 1999, due to threats from a litigious Long Island classic-rock band of the same name. If not for that, the new Light Heat album would be a Mazarin album, and could have come out years ago. The catalyst for Light Heat’s debut came from Stoltzfus’ friends and former tourmates the Walkmen. That band, minus singer Hamilton Leithauser, backs Stoltzfus on the LP, although Light Heat itself, like Mazarin, is essentially Stoltzfus and whomever he plays with. Stoltzfus will be guest editing magnetmagazine.com all week. Read our new feature on Light Heat.

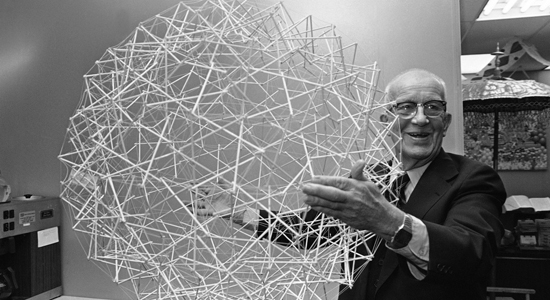

Stoltzfus: I first encountered the work of Buckminster Fuller on the Martian landscape of East Texas when I was four years old. My parents relocated our family there, along with both of my mother’s sisters and their families to start a church with a dubiously sleazy-yet-charismatic evangelical minister. He’d also recruited other families from various locales. Another story altogether, but we’re talking about Bucky Fuller here. Within months of living there, the group purchased some land in a remote area and began erecting a cluster of geodesic domes. Why they chose the structure is still a mystery to me. They certainly did not seem the type to be devotees of an esoteric academic futurist. Regardless of what became of the “church,” this cluster of domes made a lasting impression on my concept of design, and beyond that, my way of thinking about the world. I knew nothing of the man who had patented these uniquely modern structures back in 1954, let alone his design principles, his philosophy or his world-view. Throughout my teens and early 20s, I heard the his name passed around, but didn’t get around to really researching him until I came upon his essay “Revolution In Wombland,” the forward to the experimental film book Expanded Cinema. That led me to his Dymaxion designs, which completely re-thought staid concepts of transportation, living, and even how we conceptualize our view of the planet. I reached out to my friend Chris Taylor from Texas Tech’s Land Arts program for his thoughts on Bucky. He opened with a quote from Bucky’s book I Seem To Be A Verb:

“Not until I was four years old, in 1899, was it discovered that my cross-eyedness was caused by my being abnormally farsighted. Lenses fully corrected my vision. Despite my new ability to apprehend details my childhood’s spontaneous dependence only upon big patterns has persisted.”

Chris goes on to explain how this Bucky quote particularly informs his process.

“For me it’s a keen introduction to what I try to do with the Land Arts program—to expose people to the vast complexities of lived experience that is enmeshed within landscapes. Often I refer to the program as examining the intersection of geomorphology (the shape of the planet) and human construction (the shape of people’s efforts). Another big Bucky touchstone for me is his idea of the one world island in a one-world ocean within the dymaxion. Many fixate on the geodesic aspect of this map—making the sphere of triangle—and while that’s cool, the geometric clarity it offers is a second order benefit to putting all people on the same deserted island.”

This sums up perfectly the man’s true legacy: a pattern of thinking designed to re-envision the present.

Learn more about Land Arts here.

Video after the jump.