Here’s an exclusive excerpt of the current MAGNET cover story.

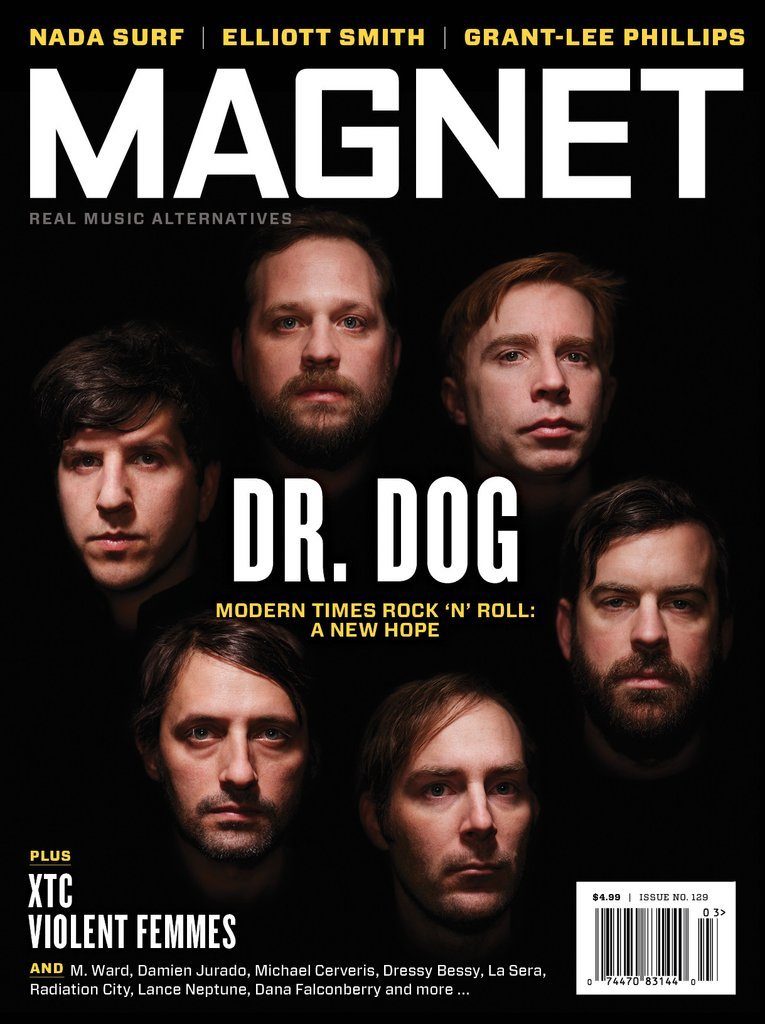

After 15 years and eight records, Dr. Dog is finally ready to release its first album. Sort of. It’s easier if we explain. MAGNET spends three days sunk to the hips in The Psychedelic Swamp with the hardest-working psychedelic indie folk pop rock American band in show business. Story by Eric Waggoner, cover photo by Gene Smirnov

Eric Slick, the 29-year-old drummer for Dr. Dog since 2010, has, by rough count and estimation, played with approximately one-quarter of all musicians currently alive and residing on earth. An early alum of Philadelphia’s fabled Paul Green School of Rock Music, Slick was the institution’s very first all-star drummer. With his sister Julie on bass, he was tapped to form the Adrian Belew Power Trio when Belew guested at the School in 2006, and was knocked out by the prodigious talent of the Slick siblings.

Throughout a young life spent seated behind a drum kit more or less continuously, Slick has played—and continues to play—with an astounding roster of musicians, including Nels Cline, Marc Ribot, Ween, premier Frank Zappa alumni group Project/Object and former members of Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band. Which is why it’s not only surprising, but contextually bizarre, that Slick cannot for the life of him recall the melody to Captain & Tennille’s “Muskrat Love.”

It’s creeping up on 1 a.m. Today’s studio run-through was a bear, and everyone’s a little jangled. Maybe Slick’s just punchy from the three days of rehearsals. So the rest of Dr. Dog starts helping.

“Come on, you know that one,” says guitarist Frank McElroy. ”It’s the one that’s got the sounds of muskrats getting it on.” Slick shakes his head, brow furrowed in a vain attempt to call it up.

“No, you know it,” presses bassist and singer/ songwriter Toby Leaman, clearly goofing as he goes into a squint-eyed, head-bobbing, Steven Tyler-style stadium-rawk stage-scream: “Aw, musk-rat luhh-huuuve! It’s drivin’ me crayyyzayyyyyy!” Guitarist and singer/songwriter Scott McMicken cracks up, as do McElroy and percussion/electronics gunslinger Dimitri Manos. Keyboard/multi-instrumentalist Zach Miller, a man not much given to boisterous vocalization, smiles contentedly.

Everyone’s gathered in the kitchen sitting area of Dr. Dog’s rented warehouse space. On the small four-top table is a tiny speaker set, through which music plays constantly when the band’s not rehearsing. Manos plugs his phone in and hunts for “Muskrat Love.” (“The Captain & Tennille one. Not the America one,” McElroy advises.) And when Tennille’s honeyed voice starts singing about Muskrat Susie and Muskrat Sam out in Muskrat Land, doin’ the jitterbug and nibblin’ on bacon and chewin’ on cheese, Slick gets such a look of guileless joy on his face, you’d think he’d been handed a kitten.

To be fair to Slick, “Muskrat Love” came up in the first place because he absolutely refused to believe so few of his bandmates could remember Maria Muldaur’s 1974 hit “Midnight At The Oasis,” not even after he helpfully sang parts of it. So, now we’re way down a soft-rock rabbit hole at something-or-other ’til one in the morning, scrolling through old AM rock numbers on Manos’ phone, listening to Muldaur tell us she’ll be our belly dancer, and we can be her sheikh.

The room is immediately smitten. ”This was a middle-of-the-road hit?” asks Manos, repeating Slick’s description of Muldaur’s single with a pleased smile.

Leaman cuts himself off in the middle of a sentence and points at the speakers: “Wait. Did she just say, ‘Send your camel to bed’?”

The talk turns to improbable hits, weird cuts, the strange deep crooked grooves in the history of American pop music. But then Manos lays down the trump card, cueing up a song he’s been marginally obsessed with for a while: “She’s As Beautiful As A Foot,” from Blue Öyster Cult’s 1972 debut album.

As soon as the song’s sinister half-step melodic descent and sneering vocals kick in, that’s the ballgame. Everyone around the sitting area loses it, tired and loopy and yawn-laughing like fools at this bizarre slice of hard-rock surrealism (“Didn’t believe it when he bit into her face/It tasted just like a fallen arch”).

It’s too much. Leaman can’t stop cackling. McElroy’s eyes crinkle up, and he tilts his head back happily. When the song finishes, McMicken goes to a small upright piano and starts fumbling around with the chord progression, quickly switching out BÖC’s surreal lyrics for the lyrics to Bob Seger’s “Old Time Rock And Roll,” a combination that is somehow even more hilarious than the original.

For the next few days, “She’s As Beautiful As A Foot” will come up again and again in the course of conversation: How did that song even happen? Someone had to write it. Someone had to bring it to the band and say, “OK, ah, here’s one … ” Blue Öyster Cult had to record multiple takes. Then overdubs. Then it had to be mastered and sequenced for the album. How in god’s name did that goofball thing make it through every single one of those potential checkpoints?

Dr. Dog will finally shake its collective head, and give up wondering. Why puzzle over it? Jesus, rock ‘n’ roll can sure be weird. Bands make all sorts of odd choices. Who the hell can say?

Adjacent to the sitting area, propped up to dry, are the gear cases for the upcoming support tour for Dr. Dog’s new(ish) album The Psychedelic Swamp. McMicken’s spent two days painting all the cases flat black, then cutting strips of blue gaffing tape and laying these over the black cases in a wide grid pattern. The stage design they’ve settled on for the tour, he says, is “sort of Tron meets Knight Rider. Like 1980s video-game graphics. But we fucked it up, like we didn’t really know how the design programming worked.”

Tomorrow they’ll start laying down tape on the huge black stage backdrop to match the gear cases and the keyboard rigs. Their tour manager, to be honest, isn’t wild about the idea. He suspects the backdrop’s going to be too fragile to unroll and roll back up every night without sustaining damage. But they’re committed to it.

As Kurt Vonnegut, another homegrown American weirdo, once said in a different context: And so it goes. Tron meets Knight Rider it is. Who the hell can say?

From the kitchen-area window of the rented warehouse eight miles out of Philadelphia where Dr. Dog has spent the last two years building its studio, you can see a short, steep blacktop road leading up and along a row of modest houses—a sign that the warehouse, a silversmith concern built in the 1920s, was here long before the nearby suburb’s family homes had sprawled out to meet it. Last night brought a cold snap. Sipping coffee, Manos says that when the blacktop is iced over, you can look out the window and watch as cars turn onto the road and brake-tap, brake-tap their tippytoe way down and past the building.

Mt. Slippery, as the band has christened its new home base, feels like nothing so much as the world’s largest hunting cabin, or the elaborate clubhouse a 10-year-old boy would build if he had modest subsidiary label funding. There’s not a thread of insulation in the entire 5,000 square feet of the joint. The whole space, which was completely open before the band started sectioning off recording rooms and bunk areas, is heated by huge metal forced-air blowers hung from the ceiling and aimed at strategic areas. Still, it’s comfortable and welcoming. A cheap plastic chaise lounge and potted elephant-ear plants sit, as if to magic-spell away the winter chill, at the far end of the sitting area.

Everywhere, there’s something to stare at. A typed set list from Brian Wilson’s show last June at World Café (where Dr. Dog is set to perform within a couple of weeks); one wall given over to a Jasper Johns-style American flag mural made entirely of playing cards; an original Dock Ellis baseball card tacked to that same wall; an ornate four-bulb lamp whose base is a statuette of a young girl in flowing robes. And all over the place are Dr. Dog pennants, stitching samplers, ink sketches, tour detritus, props from album covers.

“When we rented the space,” says McMicken with a half-troublemaker grin, “the guy we rented it from said, ‘You can do anything you want with it.’ And we were like, ‘Anything? You’re sure about that?”

Dr. Dog always wanted studio space. The first time anyone ever gave them any investable amount of money for making music, in fact, the very first thing they did was go in on an existing studio in Kensington, in North Philadelphia, that they renamed Meth Beach.

“It was a pretty rough neighborhood,” says McMicken. ”Not much around the studio. Maybe you’d go out and have a cigarette or something, but then you’d come back inside.”

Mt. Slippery, by contrast, backs up against a hillside whose bare trees this cold morning are dusted in a light snow. It’s still a modest, nofrills section of town, far more industrial than residential. But Dr. Dog is a band that seems not to need much in the way of amenities. The work this week is fueled by Maxwell House in the morning, Miller Lite and Yuengling in the evening, cigarettes for the smokers, homemade Cajun rice, meatball subs from Wawa, and music, music, music all day.

Speaking of music. The band is in rehearsals for the support tour for The Psychedelic Swamp, which is Dr. Dog’s very first album, sort of. Except the first version of The Psychedelic Swamp, recorded on four-track when McMicken and Leaman were only 19 years old, was never released officially, so this is the first official release, kind of; except the new album consists of all new recordings, except for some samples from the old version; and there are songs that are brand new to this record, and …

Deep breath. Starting over.

OK: The 2001 version of The Psychedelic Swamp, assembled when McMicken and Leaman were in their late teens, is something of a Great Lost Dr. Dog album. Self-released and heavily bootlegged in the years since the band first made it semi-public, the 2001 Swamp is a concept album, of sorts. It’s a tape purported to have been assembled by a man called Phrases, who finds his life unbearable and kills himself, only to end up in a slimy afterlife dimension that’s even more unbearable than the one he suicided himself out of.

The organizing conceit is that The Psychedelic Swamp is a mix tape made by Phrases and sent back to Dr. Dog, here in the land of the living, as evidence of a complicated paranoiac plot against humanity, largely accomplished through the dulling effects of mass marketing and media. The tape is a combination of faux-radio broadcasts from the Swamp, narrative songs, ambient noise, cut-and-splice samples from other sources (including a horse-race bugle call and excerpts from other classic “lost” pop records), and occasional character voices, both spoken and sung.

“I couldn’t understand it the first time I heard it,” says Miller, who joined Dr. Dog the summer after the tape was assembled. ”Later, I could hear that there were songs in there, but I couldn’t hear that the first few times. I don’t think I heard the story in it at all.”

“It’s a huge sound collage,” says Slick, “like an hour-long version of the Mothers Of Invention’s ‘The Chrome-Plated Megaphone Of Destiny.’ Toby told me that with enough drugs, it would make sense.”

“It’s virtually unlistenable,” says Leaman now, “except to us and a few close friends.”

“And proudly so,” adds McMicken, when I tell him the next day about Leaman’s assessment. ”We understood that all along. That was our way of justifying the ridiculousness of a lot of it. Conceptually, the fact that we understood it, but not many other people would, made sense. The idea was that this thing, this artifact, had come from another universe, with a whole other rationale necessary to make sense of it. And part two, the follow-up, translating it for the masses, was always part of the plan, too, right out of the box. The plan was always to return to it later at some point and make it more accessible.”

Leaman’s characterization of the original recording as utterly incomprehensible might be a little ungenerous, at least for a certain listener’s head space. The 2001 version of The Psychedelic Swamp was made, as he points out, when he and McMicken and original Dr. Dog member Doug O’Donnell were just learning their way around a four-track. A lot of what happens on the record is the result of that curve, experiments with delay, mucking around with tape speed and pedals and overdubs.

“There’s a lot of fat on it,” says Leaman; but what the 2001 Swamp lacks in restraint and structural cohesion, it tends to make up for in sheer unhinged determination to explore every possible permutation of a novice band’s wild creativity. Like Ween’s earliest four-track tapes—or like the Residents’ The Warner Bros. Album, with which it actually shares a lot of sonic affinity—much of the bizarro-world charm of the original Swamp lies in the technical limitation of it, the sense that there’s an aesthetic driving it, even if the final product sounds like a field recording of Martian dancehall music.

Odd as it was, the members of Dr. Dog always had a soft spot for that tape. And they loved the idea of keeping Swamp a lost record until they could figure out what to do with it, which they always planned to do. Then this year, the Swamp got a kick in the tapes, so to speak, when Philadelphia’s venerable Pig Iron Theatre Company received a grant to work with non-theater artists to mount a stage show in 2015. Pig Iron reached out to Dr. Dog, some of whose members had worked with the company on other projects.

“That sped up the process,” says Manos, “but only by a little. Going back to the Swamp was already on the table. We’d been working on a lot of new music, and for about a year and a half, the Swamp talk was building. We were already having a conversation about what we were going to do as a follow-up to (2013’s) B-Room, in what order—do we do this album of new music next, or is it time to revisit the old project? And Pig Iron came out to the studio and we talked about collaborating. And we said, ‘Well, er … here’s this project that already has a narrative behind it.’”

Dr. Dog and Pig Iron undertook to mount a joint multimedia theatrical project inspired by the 2001 record. Staged during a four-night residency at the September 2015 Fringe Festival, SWAMP IS ON incorporated video, live character performance and related live music, and an evening-closing concert by Dr. Dog. ”In the face of government interference,” the press release promised, “scientists and cryptographers will gather at Union Transfer, a former railway junction turned music venue, vowing ‘to agitate the cosmic order and commune in real time with the sights and sounds of another dimension.’”

And a glorious mess it was. ”We had people handing out flyers as people came in the doors,” says Slick with plain satisfaction, “‘Swamp Truthers’ who were going on and on about ‘The Swamp is real! The government’s involved!’ We had crust-punks playing deconstructed versions of the album’s songs on acoustic guitar outside the building.”

In no sense a staged version of the original album, SWAMP IS ON was rather an extrapolative performance that lived in the same narrative universe, proceeding from the assumption that Phrases’ tape—everything about Phrases’ tape—was real. Live onstage, Dr. Dog attempted to translate the music for the audience.

“It forced us to put the songs through different kinds of permutations,” says Leaman, “rather than trying to recapture some long ago sound.” An album featuring new arrangements of Swamp’s songs, and a reimagining of its twisted soundscape, was the logical last step. Part of what made the new Swamp feel new, says McMicken, was that even in its first permutation, The Psychedelic Swamp wasn’t an attempt to narrate an experience directly in song. The tape itself, the messy collage of sounds and speech and melodies, was meant to be a transcript of an experience—less a collection of songs than an aural snapshot of an awful landscape that one poor dead man was trying to get out into the world, with Dr. Dog’s help.

“The spirit of it was the part that was never lost,” says McMicken. ”It stayed in our conversation regularly enough that we all kept it in mind, but more on the level of an intangible quality, not a final document. There wasn’t a lot of reverence, even at the time, for what was actually hitting the tape. We were writing more traditional songs, too, even while we were putting Swamp together back then. There’s plenty of stuff we have on tape from that time that would feel too invested in to revisit this many years later. But The Swamp didn’t.

“One of the biggest curiosities for us was whether that intangible quality could be captured again. As absurd as the project could be, it still felt grounded in something tangible and real. I remember working on stuff over at Doug’s house, and then going over to 7-Eleven to get a snack, and going out into the world and feeling like nothing had really changed—the concepts we were trying to talk about, advertising and media, were mirrored by everything the world had to offer. We were trying to maintain a playfulness and irreverence. But it was also about being tuned into your environment socially and politically. The songs were very malleable, very free and flexible. I was most curious about whether that quality, that feel of being open and letting a creative dialogue happen, was going to re-emerge now.”