The making of Pete Yorn’s musicforthemorningafter

By Hobart Rowland

musicforthemorningafter couldn’t have been foisted on listeners at a less-opportune time. In March 2001, the music industry was smarting from the dotcom bust, and things would only get worse. Among the top-selling artists that year: Michael Jackson, NSYNC, J.Lo, Shaggy and Staind. Meanwhile, critics were beside themselves over the Strokes’ debut, the White Stripes’ third effort, Jay-Z’s monumental The Blueprint and Radiohead’s overrated Amnesiac.

Could a guy with suburban-Jersey roots, a Smiths fetish, a communications degree from Syracuse University and a last name that falls toward the end of the alphabet really stand a chance—even with Columbia Records’ backing? The answer was “yes and no.”

musicforthemorningafter did go gold, and it’s nearing platinum status 16 years later. But the lasting impact of Yorn’s remarkable debut was the precedent it set for others of his ilk. Simply put, it was a singer/songwriter album that didn’t sound like a singer/songwriter album: vast when you’d expect insular, hard-rocking and blunt when delicate and sensitive would’ve been the easy out, and so impeccably crafted and well executed that it could’ve only been the result of a group effort.

Yorn and collaborator R. Walt Vincent were operating in the best sort of creative vacuum—one governed by their own crazy ideas and brilliant mistakes, its boundaries dictated only by the amount of wine and pot consumed and the limitations of their ’80s vinyl collections. And it certainly helped that they weren’t on the clock. “We were not a priority at the label,” says Vincent.

It also didn’t hurt that Yorn—aside from having a shitload of great songs—had two older siblings with serious clout in the entertainment industry watching his back. Kevin, the oldest, is a high-powered attorney for superstars such as Matthew McConaughey and Scarlett Johansson. Middle brother Rick has established himself as a formidable Hollywood producer, manager and talent agent (think Leonardo DiCaprio). “I had this classic Slingerland five-piece drum set, and I gave Pete a couple of drum lessons when he was maybe six or seven years old,” recalls Rick, who’s six years Pete’s senior. “I came home one day, and I hear someone going off on my drums in the basement. I figured it was a friend. I go down there, and it’s my little brother—and he’s just killin’ it. Then he got piano lessons, and later he learned guitar and bass. We knew he had a special gift.”

The way Rick sees it, raw talent and a single-minded persistence combined to keep Pete out of law school. After college, he found his way to Los Angeles, setting in motion much of the narrative that follows.

Pete Yorn: I started writing when I was 13 or 14—just shitty songs. I was trying to sound like the Cure or something.

Rick Yorn: All through college at Syracuse, Pete kept sending me songs, and there were so many gems. To this day, I’m always the one that Pete plays a new song for. Together, we share a love of music. For many shows early on, I was his drummer.

Pete Yorn: I wrote a lot at Syracuse. A big catalyst was the cold weather. I just stayed in and smoked weed, and sometimes I’d write three songs a day. It was a lot of quantity back then. I had these crazy long-distance bills because I was always calling L.A. so Rick could check out my new tunes.

Rick Yorn: I remember that moment his junior year when my dad was still pushing law school, and I kept hearing these songs, and they were incredible.

Pete Yorn: When I graduated from ’Cuse, I moved out to L.A. with this über-confidence. I was a kid. I had no idea how the music business worked. But I was lucky. I had places to crash; I could sleep on my brother’s couch.

Rick Yorn: I remember telling mom and dad that their son was a fucking genius and they should just let him go.

Pete Yorn: From ’96 to ’98, I was playing out in L.A., trying to get things figured out. I had a band called Million, but nobody knew who the fuck we were; I think we played out twice under that name. Maybe two and a half years in, I played this show at the Roxy, and some guy from MCA offered me a deal. But it was really shitty, and I was advised not to do it.

Rick Yorn: Two key things that happened were his residencies at the Viper Room and Largo. He started getting a following.

Pete Yorn: I made a record with Don Fleming (producer for Sonic Youth and Teenage Fanclub) that was gonna be my debut record. We banged it out in maybe a week and a half in May of 1998. I was really into layering, and I’d play everything myself. I’d start with the drums and just keep building until I had the track. I was also into reverb and compression, and everything was super blown out. I was getting into Guided By Voices at the time.

Don Fleming: Pete sent me some demos before he was signed, and I was impressed with his songwriting and his style. I always found more substance to artists who can explore a darker side, and I felt Pete was really writing some great material.

Rick Yorn: The Fleming record was brilliant—really lo-fi. They made it in New York over some strip joint. It was very drug-infused … a lot of weed being smoked.

Pete Yorn: Fleming was so cool and laid-back. I re-created a lot of the demos I was doing in my bedroom, only in a studio in New York City. I was super excited about it, but it’s very “of the time” soundwise. When the 20th anniversary comes next year, I might be ready to put it out.

Fleming: I hope the full record that we made will see the light of day.

Rick Yorn: Pete had this idea to title it thenightbefore, and he owns it, so we’re thinking about doing something with it. Anyhow, Virgin stepped up and wanted the record. But they loved the first half of it, and they wanted to work on the other half, which was Pete’s favorite half.

Pete Yorn: I drank a whole bottle of white wine before I went to this lunch with these guys, and I was such a cocky little shit. “Simonize” and a lot of songs I just loved were on the second half. I didn’t understand how they couldn’t get that.

Rick Yorn: He was basically just like, “Fuck you, I’m not changing anything.”

Pete Yorn: Pretty soon after I got back from New York and was still figuring out how to get the Fleming record out, I met Walt during a smoke break at a Sloan concert at the Troubadour in West Hollywood. He said he had this digital rig and a little guest house in Van Nuys. I thought digital recording was so nerdy and not cool at the time, but I realized pretty quickly that it wasn’t so much the car but the driver.

R. Walt Vincent: The songs with just him on acoustic guitar had this alt-country feel, but I wanted to do something different with it. I wanted to try all the fun shit you could do with Pro Tools.

Pete Yorn: I had some basic tracks that I’d laid down in my basement, and I got the files to Walt. We opened “Just Another Girl,” and he laid down these beautiful, big-sounding horns and some strings. I was inspired by that, and I did some ’60s-influenced overdubs. I remember driving home listening to the song on CD and thinking, “Holy shit.” I went back a week later, and we built out another song … and then another.

Vincent: I was listening to Garbage and New Order around that time, and Pete was a big New Order fan. The Smiths were huge for both of us, so there’s a lot of that in Pete’s thing.

Pete Yorn: Growing up, I was into Britpop and other bands from England, but I was also getting into Neil Young, Led Zeppelin and the Stones. musicforthemorningafter is a blend of that. When we were making it, I was really into Teenage Fanclub; I was really into Wilco and Son Volt. I could’ve made a straight alt-country album.

Vincent: We’d get the basic track down, and then just really fuck around. We sort of fell in love with the randomness. We’d goof off, then one of us would get serious, and the other would say, “Dude, what are you talking about—that’s the shit.” A lot of the ideas came from us not trying to be cool. It was like, “Rather than fight over an idea, let’s do another idea.”

Pete Yorn: We had a really good groove going, but it was laid back. By June of 1999, we had early versions of “Just Another Girl,” “Life On A Chain,” “Lose You,” “Sense,” “Black” … I remember I just laid down the drums to “Black” and went off that. Walt brings this extra emotional weight with these melodies I wouldn’t normally hear in my head.

Vincent: What got me about Pete was this sensitivity. What really moved me in his songs was what I called “the tug.” That sort of became my go-to word—looking for that brokenhearted, emotional thing. It’s something that’s deep inside Pete, and I wanted to get that out. He’d been used to lumberjack singing onstage with a drum kit behind him. But I was like, “Dude, sing quietly; get right next to the microphone.” I’d adjust his headphone mix so his voice was super loud, and he had no choice but to sing softer if he wanted to hear the track. That brought out a lot of the tug of Pete’s voice, which is why I think people really connect with the record.

Pete Yorn: Working with Walt was such a new process that I was writing songs in the studio on the fly. I was going through a breakup with a longtime girlfriend at the time, and “Lose You” came out of that. Unconsciously, a lot of stuff was pouring out of me.

Vincent: Some people at the label didn’t think I existed at all; they thought Pete made up my name so they wouldn’t think he was doing it all by himself—like he was trying to create this mythical producer so they wouldn’t fuck with him.

Pete Yorn: At some point, we finally got a meeting with Columbia Records. I go to see (Columbia president) Donnie Ienner in his office with my guitar, and Donnie’s smoking a cigarette. He’s like, “Play me something.” I play “Murray,” and he goes, “That’s pretty cool; what else you got?” I play “Just Another Girl,” and he’s like, “We’ll let you know. Thanks for coming in.” And that was it. I didn’t hear anything for weeks, and then Donnie’s top A&R guy, Will Botwin, comes out to L.A. to check me out. As fate would have it, I was just over at (producer) Tony Berg’s house, who lived nearby. He showed me this chord on the guitar, and I went home and wrote “Life On A Chain.” Will comes to see me and asks if I have anything new. I play him “Life On A Chain,” and he goes, “All right, let’s do this.”

Vincent: If you listen to “Life On A Chain,” it will swing and not swing at the same time. When I came up with the bass line, we were both busting up, because it had this “go, greased lightning” feel. Then I dug up a sample of some record noise, and I was like, “Now it sounds like the song starts in the ’40s and makes a jump into the 21st century.”

Pete Yorn: I’d been working with some unknown dude in a home studio in the Valley, but I was really confident in the music we were making. I had no illusions that working with a big producer was gonna do anything.

Vincent: The label was pretty hands-off. We made the entire record in a 17-by-18-foot room, so no one wanted to come hang out. There were two chairs; one of us was either sitting on the floor or an amp. There was no AC, and you had to go into my house to go to the bathroom. It was not a comfortable place to hang out if you weren’t involved in the process, and there was really nothing to see but the back of my head and a computer screen. It wasn’t about the pinball machines or the fruit bowl. We were just fired up about making music.

Pete Yorn: I did meet with other producers. I met with Butch Vig, and the scheduling didn’t work out. But he was an early champion of the stuff we were creating. And then we get to Brad Wood, the guy who produced (Liz Phair’s) Exile In Guyville. He had a great track record with debut records. We sent him our stuff, and he called back pretty quickly and was super excited. He said, “Man, I love what you guys are doing—I don’t want to fuck it up. I just want to help you finish whatever you’re doing.”

Vincent: There was some pressure to toughen our shit up—“Closet” was a good example. It was like, “Dude, we’ve got to have a rock song we can get on alternative radio.” I didn’t do “menacing,” and Brad had a lot of experience with that.

Pete Yorn: It had been just me and Walt in the zone for so long—two of us in this little garage. We’d work for 16 hours straight before we even took a breath. Then Brad comes in, and he’s a little bit of a chatty guy. Finally, I said, “Brad, no more talk. Let’s just get into it.”

Brad Wood: When they hired me, I was adamant about continuing to work with Walt. The stuff that I liked the most from Pete was the stuff that was done with him. I remember telling Pete over the phone, “Whoever this R. Walt guy is, I want to fit in with that.”

Pete Yorn: Brad had this great ear for hearing where there was a hole in the production, or it needed just a little extra thing to keep it interesting throughout. If you listen to “On Your Side” on headphones, you’ll hear this Wurlitzer piano countermelody, and when the song fades out, there’s a high, Peter Hook-style bass line that he pulled out of me. For the kick drum on “Strange Condition”—that big, roomy sound—Brad brought in this giant Slingerland marching drum. He’d come up with these really cool extra parts, and he mixed the record, as well.

Vincent: Technically, Brad has amazing ears, and he just totally schooled me on what to listen for.

Wood: I was producing, for sure, but it felt a bit more like executive producing, where I was overseeing the big picture. My concern, right away, was not having things sound too dated too soon. A lot of that was alleviated by focusing on who Pete really loved as a songwriter. Springsteen figured huge, so I was adamant about songs like “Murray” being on there, and that we had a big, bold drum sound that was almost like a stadium sound, because that’s what we were shooting for. That’s what he aspires to, and some of his sentiments are epic.

Pete Yorn: Walt moved to Culver City, and I was so worried that we’d lose the magic from the Van Nuys place that I took a little plastic water bottle, spun it around in a circle and collected air from the Van Nuys room. When I went to the Culver City garage for the first time, I squeezed it in there. We worked with Brad in Culver City through the fall of 1999, and then we took a break for Christmas. I got back to Walt’s after the new year, and out of nowhere I recorded “Sleep Better” and “EZ.” “Simonize” is the one song from the Fleming sessions that made it on the album.

Vincent: It was Brad’s idea to transfer everything to tape to give it this saturated analog feel. When I first listened to the transfers, I thought the guitars just sounded so warm and beautiful.

Pete Yorn: We were mixing the recording at the Record Plant, and I wasn’t getting that feeling; it wasn’t right. I remember we really got into it with Brad. Then something clicked, and he started nailing it.

Vincent: Brad knew that the way to finish it was to dump all the shit onto tape and mix it off the tape, because that’s going to glue it all together.

Pete Yorn: We were mixing musicforthemorningafter, and I got the call from Pete Farrelly, who wanted to use “Strange Condition” (in the 2000 Farrelly Brothers film Me, Myself & Irene). Then he was like, “You wanna score it, too?” I was focused on finishing the record, but I had to do it. Walt helped me, and we did this sort of homespun thing. musicforthemorningafter was done and turned in a good year before it came out. People heard “Strange Condition” in the Farrelly Brothers movie, but they couldn’t get it anywhere.

Wood: We had a ton of time and a ton of songs. It was really obvious that “Life On A Chain” should be first, because it sounds like a needle drop. One of my favorite songs didn’t make the cut (“Knew Enough To Know Nothing At All,” which is included on the 10th-anniversary reissue). I was heartsick about it.

Pete Yorn: The whole singer/songwriter thing wasn’t happening, and people kept telling me I should have a band name. They sent it out to the press to get a gauge, and the response was just so overwhelmingly enthusiastic that it really pushed the label to get it out there.

Rick Yorn: Columbia loved the record, but they didn’t really know what they had.

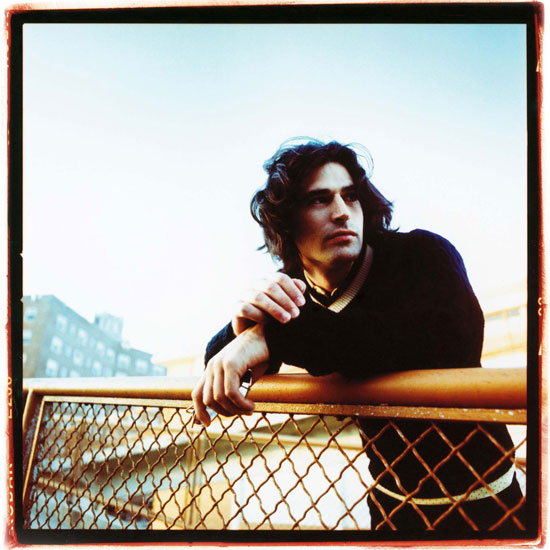

Pete Yorn: The cover photo was actually taken on a whim in a back alley in Hollywood probably in 1998 or early ’99. I was actually walking to a gig. I just thought it had a strong vibe. Months later, after I’d signed to Columbia and it came time to make the packaging for the album, I was stuck on that photo. We did other shoots to try and beat it—even with (high-profile photographer) Danny Clinch in Asbury Park, N.J. But nothing ever came close for me. So, yeah, the cover shot was taken on a crappy disposable camera by an old friend who’s not even a photographer. Just one of those things, I guess.

Rick Yorn: “Life On A Chain” was the first single, and “Strange Condition” was the second, and they were both one and two on the record. But there were so many other great songs that never got worked.

Vincent: For better or worse, the album was really hard to categorize and hard to promote in an industry that was so segmented. Part of the beauty of musicforthemorningafter is that we were just making songs. We weren’t trying to be anything.

Pete Yorn: I didn’t know who was gonna like the record, but I knew I liked it, and it felt really fresh to me—a little mysterious, too. I didn’t understand it all, but in a good way—like a girl you don’t know too well because you just met, so she seems even more interesting. Somehow, over time, the songs have kept their mystery to me.