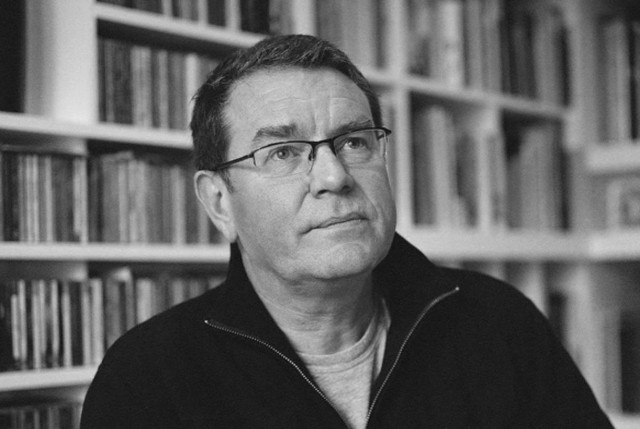

Cheryl Gelover and Tom Murray of Tulipomania remember their collaborator and friend Vaughan Oliver, the legendary 4AD Records graphic designer who died December 29

The dark-yet-cathartic images contrasted and simultaneously married with the sophisticated typography struck a chord with us, and their visual power always related to and enhanced the amazing music they enclosed. A sense of being connected with a world of music and art we had no geographical relationship to was afforded us.

We are so grateful for the opportunity to have worked with Vaughan Oliver. Chance and the randomness of life somehow allowed it to happen. Why Vaughan fostered and supported our music and filmmaking is mysterious. Luck and timing somehow aligned.

He had nothing, obviously, to gain by working with us, and yet it happened.

Mingled with a deepening sense of sadness at the loss of the immensely talented Vaughan Oliver and of his passing at the far too young age of 62 is an equally deepening sense of our good fortune at having been able to begin to know and appreciate him. We benefitted from the experience of having artwork created for us, and then were supported and complimented on our own visual art and finally were allowed to create alongside Vaughan and under his direction. We don’t know if any others have had both experiences, but we may be somewhat unique in having been both clients and collaborators on visual projects.

It would be easy simply to say we were thrilled to have known Vaughan as a gifted visual artist who had the rare ability to enhance the experience of music with distinctive, evocative imagery. What is wrenching is the sense of having lost so much more in the person of Vaughan Oliver. Vaughan’s mordantly witty response to life’s twists, turns and outright roadblocks was at first a surprise to us, then a constant delight. After experiencing numerous setbacks and difficulties while working together on projects—we struggle to remember the specific issues in most cases while it is easy to recall Vaughan’s humor, energy and wit. He embraced challenge and created solutions.

In 2012, we were thrilled when Vaughan responded enthusiastically to an animated music video we made for one of our songs. His encouragement and support were inspiring. He was equally enthusiastic about other animated videos we felt emboldened to send his way, and he was also openly honest in his less than enthusiastic response to one project we hadn’t entirely maintained control of. The theme of aesthetic vision and control was often a topic of our conversations.

So began a dialogue between us—marked by candor, openness and complete trust and admiration for Vaughan’s aesthetic judgment on our part—and to our delight, a growing feeling that we may be able to work together on moving imagery.

In a thrilling moment, Vaughan agreed to create artwork for an album and the singles we were finishing and planned to release. In other thrilling moments, we batted around ideas for how to collaborate on moving imagery for as-yet-unknown projects.

All the while, life’s little roadblocks popped up along the way.

We sent a bank transfer in what we believed to be a sign of good faith for creation of the album artwork, from what we believed was our perfectly reputable American bank to what he believed to be his perfectly reputable British bank. Funds refused to cross continents. (An international financial incident created by an attempt to transfer funds for an album titled This Gilded Age?)

Phone calls, emails, physical visits to the banks on both sides of the Atlantic could not rectify the situation. Vaughan’s response: “Blimey. I’ve never had so much dialogue with a band pre CREATIVITY!”

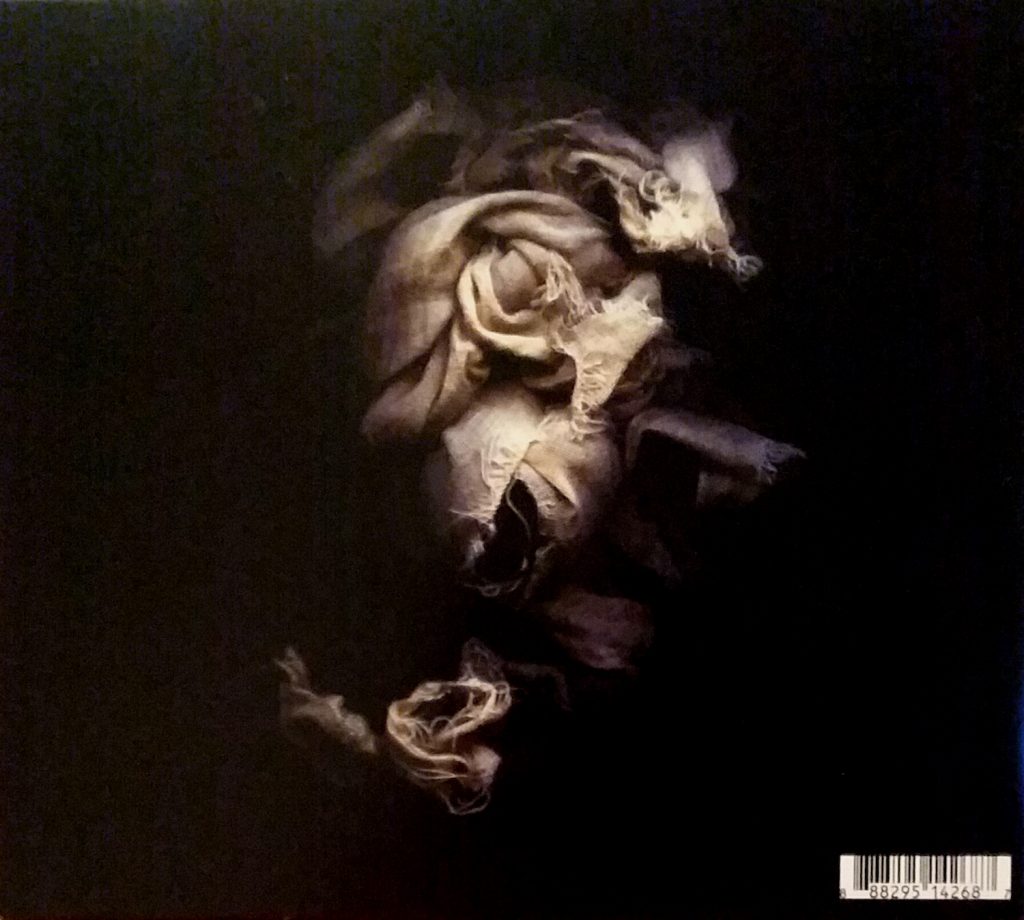

When we finally moved on to the creativity, Vaughan told us not every artist would have accepted his concept: a completely textless album cover. The beautifully photographed imagery by Tim Lee was to stand alone, with text only on the spine. We loved the idea. Vaughan was to have complete aesthetic control.

Unfortunately, the printer intervened. The albums were printed with the addition of a large black and white bar code directly on the cover. Vaughan’s response was a string of really funny expletives—if either of us remembered well enough to quote them we would. We did not accept the print job.

The covers were printed three more times before the project was finished. The wrong template was used, placement of images weren’t correct, etc. Vaughan’s response, after laughter, was to request that we send samples of each ill-printed cover, so that he could use them as examples for his students. He often talked with us about his students and his love of teaching.

Our lesson: Do not accept less than what you have intended to create. We gained so much more than a beautifully designed album, poster and singles.

Vaughan first met with us in person in London, and we talked for hours in a little pub near Greenwich, where he was teaching. Meeting in person changed things.

You never know if you will hit it off with someone you have mostly interacted with by text and phone. We became much closer after laughing together in person with suitcases piled around us—we had been so excited to meet him that we had come directly from Heathrow. We talked more about working together, and we made arrangements to meet for dinner with him and his partner Lee.

We learned about Lee’s efforts to house Vaughan’s artwork, including sketches and the camera-ready art used to create albums in a physical archive as well as an online archive and printed publication. Vaughan Oliver: Archive, was created, and a second printing is now available from United Editions.

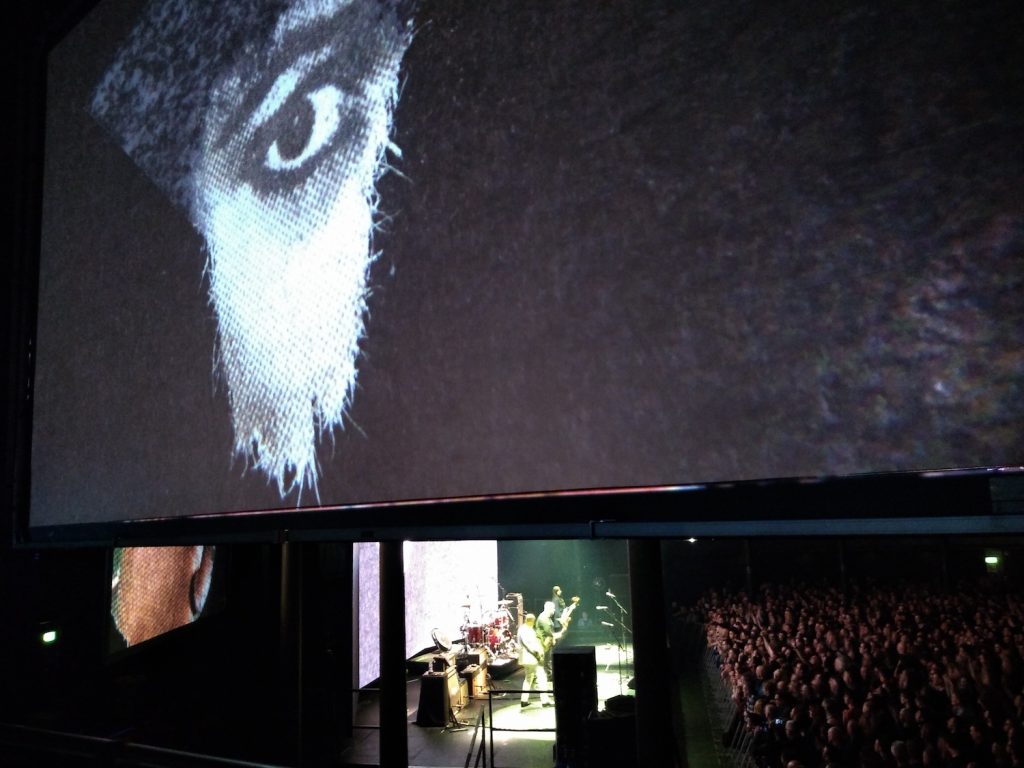

We opened our copy in late October 2018, just before leaving for England to join Vaughan in London for Pixies shows that included animation we contributed under Vaughan’s direction for background projection at the 30th anniversary multi-city performance series of Come On Pilgrim/Surfer Rosa opening at the Roundhouse.

We were completely unprepared—and yet thrilled—to see that Vaughan had included his artwork for our album and single on pages 170 and 171 of the printed archive edition.

In London, before the Pixies show Vaughan treated us to dinner at manna, explaining that it was one of the city’s oldest vegetarian restaurants. His son came along and let us in on a little secret: Rarely did Vaughan spend time searching for restaurants online, but he had carefully searched for a nice place he knew we would like.

We discussed how we were pleased with how our animation process worked well with the original artwork for Come On Pilgrim/Surfer Rosa. We created more than an hour of animation for the concert series and Vaughan directed some additional video by some of his students, typical of his concern to provide opportunities for his most talented students. Unfortunately, we hadn’t been able to realize an overall aesthetic control for the shows’ visuals, and so Vaughan’s original concept was not to be.

We worked under Vaughan’s direction for months creating the animation, but hadn’t fully considered the means to realize Vaughan’s overall vision for the visual experience. What we finally saw on multiple screens was good enough—but fell short of what Vaughan envisioned. The nature of the live aspect of the presentation of our yearlong planning and months of animation effort only allowed for limited revision and rework. The show must go on.

In an email following the show, Vaughan wrote he appreciated our “plain talk” about the aesthetic issues, but he concluded by noting that we had all enjoyed ourselves, and bonded over the experience. We had. After having completed a project that required extended rework and would have required more overall directorial control to fully realize, we had, in fact, enjoyed the process and learned from the experience.

Vaughan was unfortunately too ill to attend the second and closing evening of Pixies’ London performance. We had met one of Vaughan’s sons on the first evening. Lee and Vaughan’s other son attended the final performance of the London run with us. We were so happy to see Lee again and meet his son, but we were sad not to see the closing performance with Vaughan and we worried about his health. We later learned about the extent of Vaughan’s serious medical condition. We had several interactions by email over the past year, but we had not talked with him since. A major regret.

When Vaughan wrote in response to our birthday greeting this past September 12 that he was “in great spirits” and was “easing his way back into work,” we were looking forward to more discussions on ironing out aesthetic details on future projects. We are heartbroken now. The process of working with others is all there really is. The artifacts, beautifully realized or fraught with compromise, are the results of the process. We loved Vaughan’s work when we did not know him at all. We are thrilled to have had the chance to get to know him and feel lucky to have ever had the chance to work with him in any capacity. He made everything about the process feel like a success. Obviously, he knew what he was doing.

Vaughan was so passionate about art and music that his critiques throughout the process were enormously entertaining. He seemed to burn so hot—we wondered if he would survive his trip home after we were together. If we had one last chance, saying thanks in person would be what we would wish for. And we would have asked to take a photo together.

Surely the University Of The Creative Arts Epsom—the design school where Vaughan had a visiting professorship, and the location housing the archive—could use donations in Vaughan’s honor to ensure the future of their efforts.

It would be wonderful to be able to see a major retrospective exhibition of Vaughan’s work. For now, Vaughan’s lively, messy, willing-to-work-it-out spirit, as well as his fully honed artistic vision, is honored at United Editions.

Love to you, Vaughan!

Thanks for introducing us to Lee, Beckett and Callum.

Our thoughts are with you all.

For everything, we are very grateful.

—Cheryl and Tom

Read Vaughan in MAGNET on his Pixies album art:

A 1990 interview with Vaughan: