While sitting at his home in Gainesville, Fla., David Gordon apprehensively chats about his forthcoming FUNKILLER record. Talking about his own music is not Gordon’s strong suit, though he comes alive when his earnest sound is likened to the late Daniel Johnston.

“I actually have an original piece of his,” he says. “It says, ‘You can go crazy too, but don’t ever come back.’ It’s a beautiful thing.”

For those not living near Gordon in Florida, in some nearby Spanish-moss-covered town, you’ve likely never heard his lush, poetic music. He’s only released one album, 2005’s On Cemetery Road, and since then, he’s rarely played live. Instead, he’s been slowly chipping away at his upcoming Tropical Depression.

The 10-track album spirals freely, never clutching to a specific genre. From harmonious, airy ballads that’d make Brian Wilson smile to trippy, Flaming Lips dream pop, Tropical Depression delivers a classic listen-on-headphones experience. “Rattlesnake Freight Train” even delves into an ethereal Joe Meek/“Telstar” arena that quickly dissolves into some Cramps-tripping-on-acid rock ‘n’ roll. Somehow, Gordon’s music is still seamless and obviously cut from the same sonic cloth.

While Tropical Depression won’t be out until the fall, lead single “Divided Highway” was recently debuted by LaunchLeft, a Los Angeles label/podcast operated by his bandmate, Rain Phoenix. Rounding out the lineup is another Gainesville resident, David Lebleu of the Mercury Program.

MAGNET conversed with Gordon about his life as a reclusive songwriter, but also about some of his favorite albums by other artists:

You’ve only gigged a few times over the past 15 years. What keeps you away from the stage?

I don’t really think of myself as a performer of sorts. I’m more of a writer/artist and also kind of introverted. I don’t want to share until I have all of my creative stuff ready to go. It takes me time. Most people probably thought I just didn’t make music anymore. It’s true, I haven’t been playing many shows, but I’ve been talking to Rain Phoenix at LaunchLeft about it the whole time. She was in my corner and was encouraging.

I know Rain—and the entire Phoenix family—have strong roots in Gainesville, but how did you meet?

I was doing my thing with Dave LeBleu, and he was making music with Rain. She was singing on some of his stuff. One day, she saw me play and then came to The Top, the restaurant I run, and we talked. She decided she was going to do harmonies. I was looking for someone who could take the edge off my voice and also create another dimension of sound. I was thinking about her anyway, and then she showed up.

Rain sings on the new album, adding a beautiful layer to the equation.

She flew in so she could sing on the whole record. FUNKILLER is kind of billed as this one-man band thing, but I’d rather talk about the other players. They are all pivotal. I couldn’t have sung with any other siren than Rain. But her sister Liberty sings with me, too. Both of them keep me going. They are kind of like a spark. We are connected somehow, cosmically. Really, their whole family is out there fighting for people. They run the River Phoenix Center For Peacebuilding here in Gainesville. They’re just setting the examples.

Well, the album sounds great. How was that process?

Yeah, that’s what I’ve been doing with my life secretly for 13 years. My previous one, Cemetery Road, was very stark. I played on my mother’s guitar. I wanted to do a kind of litmus test. It’s me and Dave Lebleu, who’s still my drummer. But Tropical Depression is a different thing; it’s the opposite of that. I played more piano and accordion, making something I imagined would be more musically complicated. I’ve got my beard hairs crossed that someone is going to give a damn once it’s released. I don’t know what will happen, but I’m putting myself out there for the first time, really, being vulnerable.

It seems like your lyrics take time to write. Is that something you dedicate a lot of time to?

My process is such a strange one. I studied creative writing in school, and I care about syntax, lexicon and the power of using words uniquely. I care about that so much. I’ve always strived to be a great writer, really. If a word or inflection feels not natural, I can’t let it stand. Same for a musical note or bridge. I’m my own harshest technical editor. I’m very specific about my words and really care about the music being unique. But music is in my blood a bit; I do it kind of intuitively—kind of Daniel Johnston-esque. Even in his music, you can hear all of these things that he hears vicariously, like the Smile sessions or the Beatles. I am a fan of Daniel Johnston, and I do, in a way, see myself in that vein. I do kind of struggle with my mind a bit, though not like him. I am highly functional in a lot of ways. As for my music, I am not classically trained or anything. In the words of Bill Withers, “I’m no virtuoso.”

Do you dig the Beatles as much as Daniel did?

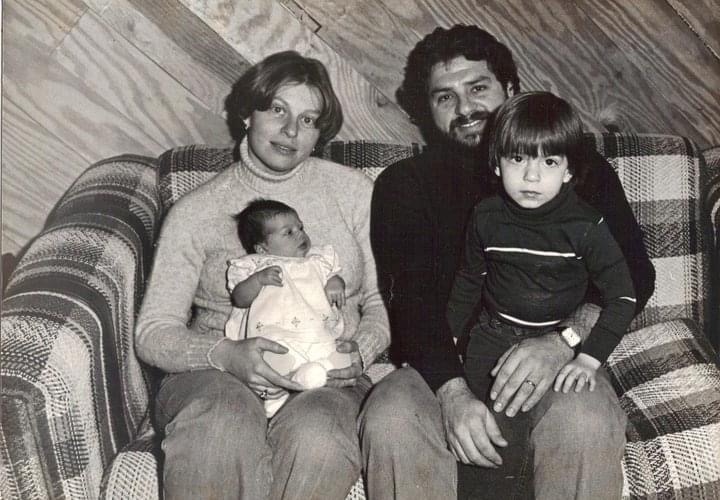

To be honest, at one point in my family’s life, my dad worked for Yoko Ono as a bodyguard. I’ve never told anyone or talked about this publicly. He worked for her, and I grew up wearing Sean Lennon’s hand-me-downs. The Beatles had an effect on my life, personally and meaningfully.

So, you were kind of born into the music world, huh?

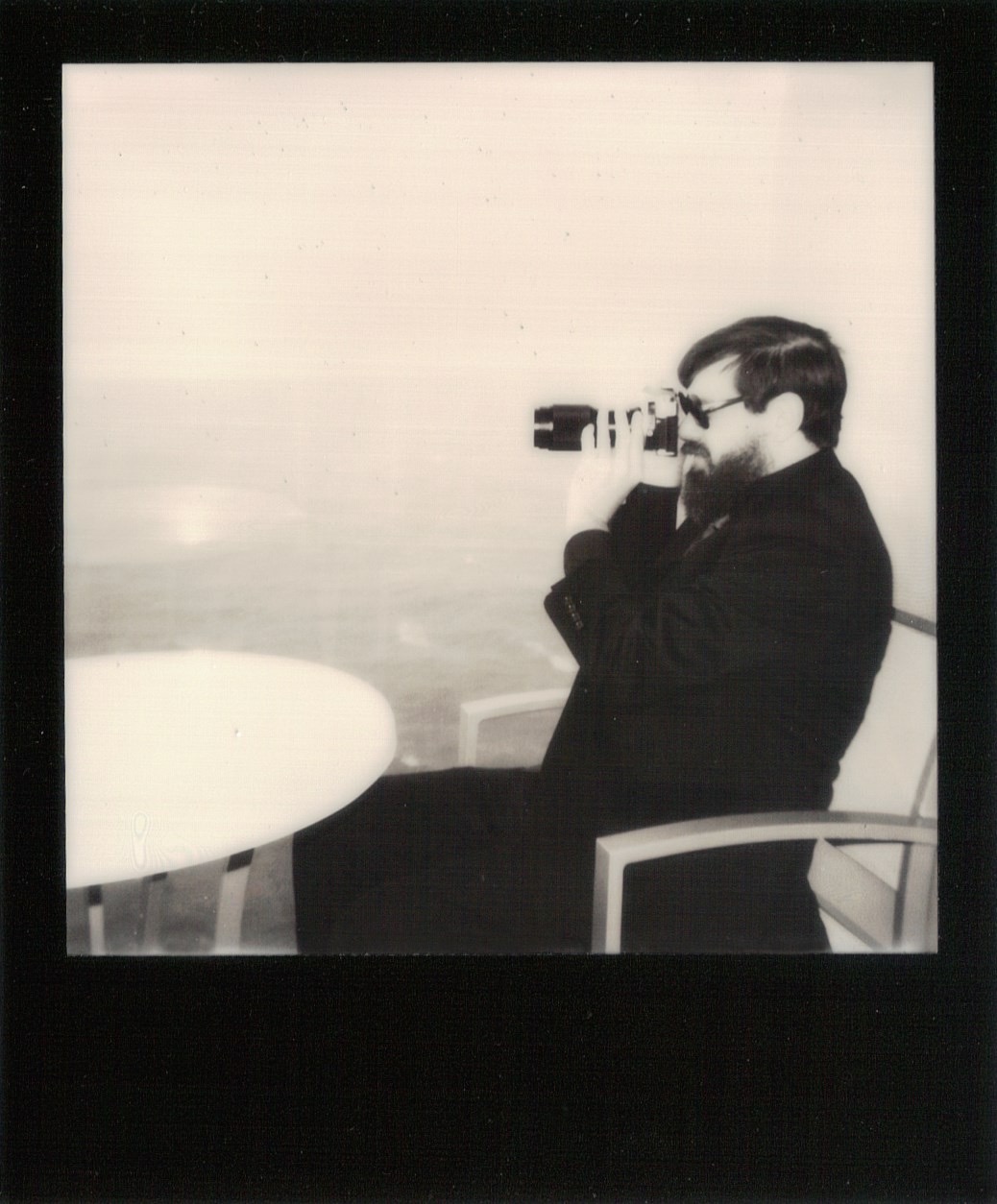

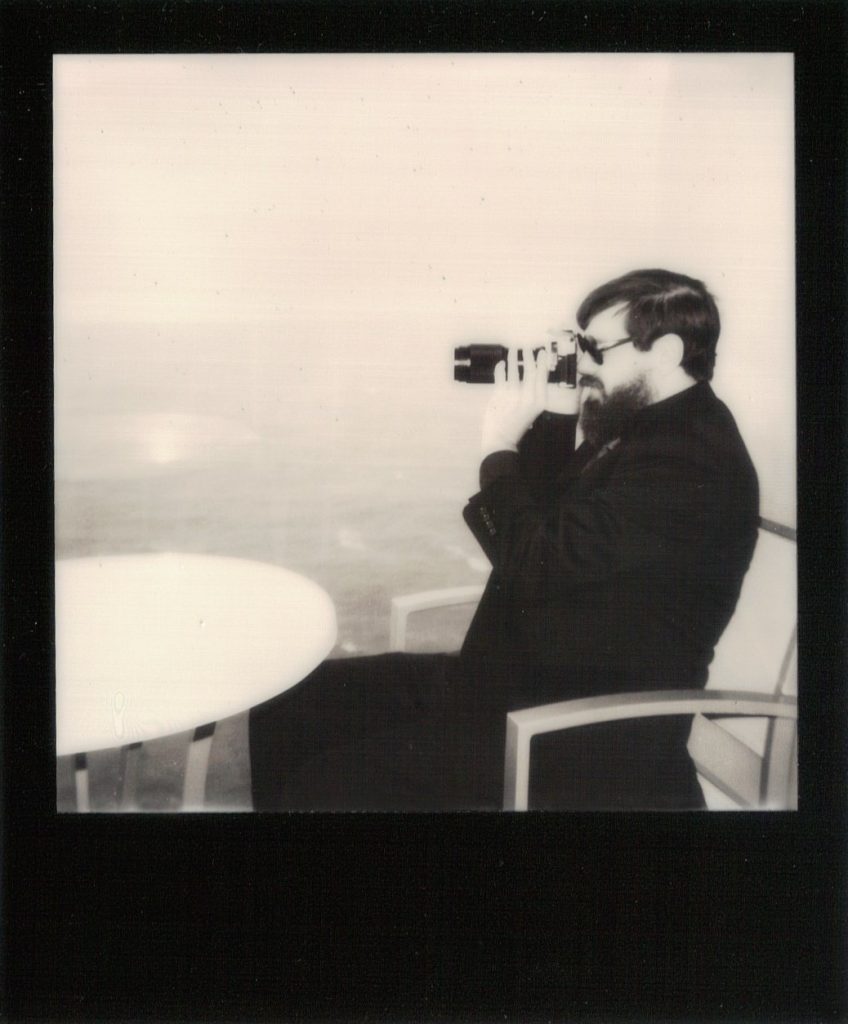

I wasn’t really in their world, but I was juxtaposed to it. Yoko was very generous to my dad, who didn’t really care about music. He was a cop in New York, a war veteran. I’m rebelling against him eternally. My mom was a musician in the city, a Greenwich Village musician. I had this dichotomy of my dad and mom. My mom was a photographer, too. She went to Pratt in New York. I am also a photographer. That’s where I probably got it from. They gave me my dad’s Vietnam camera. It’s a Minolta SRT-102 with a telephoto lens. That’s the one I still use today along with the Polaroid from my childhood. As always, I prefer the original. I have my special instruments.

So your father worked for Yoko as a bodyguard?

He was actually Sean’s bodyguard after John was shot. They would talk about it all the time, and I would get things from Yoko. So, the Beatles—and especially Sean and Yoko—were always a glow to me. I love Yoko as an artist and everything she does, but I am partial to one of her records, Feeling The Space. I hold it so dear. People don’t know about it, but it’s so lovely. John plays on a lot of it. It’s got the Plastic Ono Band. It’s known, in some circles, as the first feminist record. The cover has her head on a pyramid. It’s super-timeless looking.

Yoko was such a pioneer of experimental music. Does it go in that direction?

The strange thing about this record is it doesn’t have that. It honestly sounds like a lost, early Blonde Redhead record. It’s definitely something that got lost at the time, but it’s such a beautiful thing.

I’ve been digging back into Willie Thrasher and his Spirit Child LP. The reissue on Light in the Attic Records is amazing.

I’ll check that out. I’m a big fan of Light In The Attic and a huge lover of Rodriguez and Searching For Sugarman. I love the Jim Sullivan stuff. Honestly, I’d love to talk about anyone’s music but my own.

Well, we’re accomplishing that, but it all connects. Everything you hear and love tends to seep into your own music, but you’re good at melding them all. It’s hard to pinpoint what era you’re most inspired by.

Well, that’s good. I wanted to make the record that way, so it’s music to my ears. I wanted to go for something spanning. I always err on the side of mystery. I like a good persona. I love the band Clinic—they are one of my favorites. I’ve always had an affinity for the antihero: the person who is into the art, not the showmanship. That likely feeds into my not wanting to play live—or play the same songs around town all the time.

Staying home allows more time for songwriting. It worked for Brian Wilson, right?

Exactly. And I lived in Athens, Ga., for a while, where Jeff Mangum (Neutral Milk Hotel) does his own thing. He wrote something so incredible, and then he disappeared. I guarantee he’s been working on something this whole time.

Going on the road can drain some people. These days, at least you can play on the internet, I guess.

It’s true. The world has definitely changed, especially with this whole pandemic. There’s a lot of “live from the living room,” which is fine by me. I never really travel very well. I’m kind of neurotic. I kind of struggle outside of my comfort zone. I’d rather be here with my pianos and cats. [Laughs]

It’s been so long since your last album. Why now?

I’ve worked on this for 13 years. I’m very uncompromising. I only want to play with the players I want. Everything has to be special, so it takes a long time. But I recorded in the summer of 2018. I went up to this place called Montrose Recording in Richmond, Va. It’s a really beautiful studio. It has the Sparklehorse soundboard. They have a Flickinger console. It’s pretty rare. I am all analog. I like my antiquities, so I loved it.

So it was the board that drew you to Montrose Recording?

I was allured by the soundboard, and I kind of waited for a serendipitous window to open before I booked time. I wanted to find that perfect place to record in an uncompressing way. My friend and closest collaborator, Brent Delventhal, does this band called Warren Hixson in Richmond. He owns two restaurants up there. We’re both restaurant people at heart. My parents owned a restaurant, and I run The Top in Gainesville, so we have that in common. The food/music thing is a tale as old as time. It’s like I Like Killing Flies—you’re just kind of born into it. Music is this balancing thing for a lot of restaurant people. You have to have the outlet while also being the humble servant.

So you and Brent were almost destined to work on this together?

We have always wanted to make this record. He does all of the guitar work and kind of produced it, in a way. He guided me. He put me in a comfortable place, musically. We created a little world where I felt like I was at my house.

After the recordings were done, what came next?

After that, it was working on the art uncompromisingly. My friend is this artist, Amy Grantham. She’s so wonderful. She’s one of my oldest friends. She made a documentary, Lily, about her fight with breast cancer. She has become this famous collage artist and does these surrealist paintings. She also ended up marrying Graham Nash, coincidentally. But I wanted her aesthetic. Like me, she has a lot of water themes. I was looking for that Islands In The Stream, Hemmingway feel. I knew it had to be her. I choose my characters very carefully, and I can’t see it any other way. Like how I waited so I could get Rain on the record. It all had to happen in an exact way, in an exact time and place. I got all of my stars together, and they aligned.

—Rich Tupica