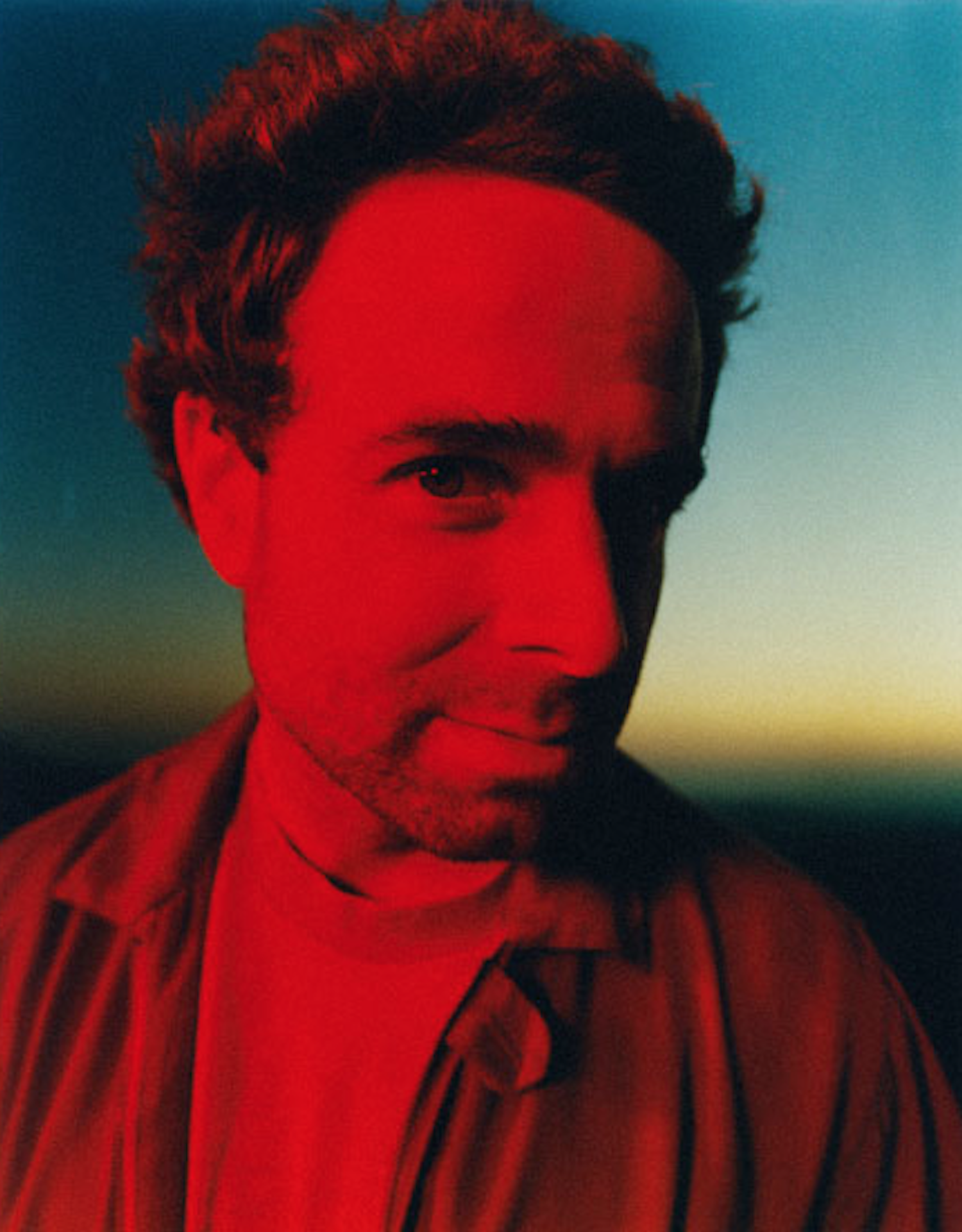

Dawes has been nothing if not consistent, releasing an album every two years (or less) since its 2009 debut. And with the rare exception, the quartet has been consistently excellent, evolving quite organically from the frumpy, earnest Band-inspired heartland rock of its early efforts into a more varied and sharply honed vehicle for bandleader Taylor Goldsmith’s increasingly empathetic outlook on life and vastly matured narrative sensibility. At this point, if he ain’t the next Jackson Browne, then he’s a remarkably skilled imposter.

It’s been a fairly busy few years for Goldsmith. He married actress/singer Mandy Moore in late 2018, and his band signed a deal with Rounder. Almost like clockwork, Dawes’ new album, Good Luck With Whatever, arrived 27 months after Passwords, which, like its 2016 predecessor, We’re All Gonna Die, ratcheted upped the studio tinkering to obsessive levels. Working this time with white-hot Nashville producer Dave Cobb, Dawes splits the difference between the relentless sheen of We’re All Gonna Die and the live-to-tape feel of 2015’s All Your Favorite Bands (Dawes’ highest charting album to date). It’s a winning compromise, largely thanks to some of Goldsmith’s most pointed personal observations and potent storytelling.

MAGNET chatted with Goldsmith about married life, new beginnings, tolerating imperfection and the allure of Joni Mitchell at her jazziest.

How’s married life treating you? You’d think a pandemic provides the ultimate test for a new marriage.

Despite the circumstances, we’ve gone out of our way to enjoy it. Mandy and I love hanging out with each other, so it’s been great. We’re probably not going to have time like this again, where it’s just the two of us hanging out, until we’re old retired people.

Good Luck With Whatever is out, so what now? Obviously touring is out for the foreseeable future.

We’re going right back into the studio, though I’m not sure that’s the best business model. We love this new album, but at the same time, what else can we do? We can write songs, and we can record. Our choice is to either do nothing or do that.

You released the last four albums on your own label. How did the deal with Rounder come about?

Our philosophy at HUB was as a few cooks in the kitchen as possible. But then, after a few albums, we’re were like, “What if we do the opposite?” Meanwhile, our lawyer, John Strohm, stopped being a lawyer and became head of Rounder. It felt so serendipitous—that the guy who’s had a longer-standing relationship than anyone else with the band is the guy who’s the head of our new label.

It seems everyone is seeking out the services of Dave Cobb these days. What was it like working with him?

He forces the whole experience to move at the fastest pace possible—and that sounds uncomfortable, which it is. I think that’s why he’s so effective. We’d sit down on the couch and play him a song, and we’d do these little adjustments. Then we’d cut it live—all four of us, with me singing the lead vocal. Typically after the second or third time, he’d say, “Great, that was it. Let’s go back to the couch and do the next song.” He makes it so an artist can’t overthink.

Do you feel like you’ve gotten any pushback from fans on the more commercial direction of the previous two albums?

For us, each album is a reaction to the one before it. But I’m never really sure what that means until it’s done. We didn’t think We’re All Gonna Die was that radical when we were recording it. Some people loved it, and some people didn’t. Then some people told us Passwords was lush and rich but really mellow. And I was like, “I didn’t realize that, but I guess you’re right.” With our last two records, we really enjoyed building tracks. With this one, we wanted to minimize that. It’s fun being in a quartet, and we wanted to emphasize that.

“St. Augustine At Night” and “Didn’t Fix Me” seem to represent the opposite poles on this album—the narrative storytelling versus the more confessional stuff. What’s the story behind the first one?

I have relatives who live in St. Augustine, Fla., and every time we go on tour, I visit. We go fishing and have a fish fry. We hang out at the local bars, and everybody knows everyone else. I’ve never lived anywhere but L.A., so there’s a romance to that. I like the idea of finding solace in a hometown. Wherever you come from, no one else can interrupt that relationship—even if you never go back.

“Didn’t Fix Me” feels personal, and yet its sentiments are universal.

Some of it’s fabricated. I wasn’t nominated for an award. I didn’t read a book about a spy in Germany. But the concept was very true to me. I’m probably the happiest guy I know, but we all find ways to suffer. And when anybody gets wind of that, they suggest this easy-fix cure-all based on their own experience. The way I’ve behaved as a songwriter isn’t too different from the way I’ve behaved in dinner conversations throughout my life. If you had dinner with me at 24, I might talk about myself a lot—and I’d share a lot of private information that was probably a little indiscreet. When you’re younger, it’s easier to mistake good songwriting for airing your dirty laundry. Now, I want to look at things from a different perspective—whether it’s “St. Augustine At Night” or ”Between The Zero And The One”—or recognize when I don’t need to have an opinion—like “None Of My Business” or “Good Luck With Whatever.”

You vocals have really evolved over the last several years. It’s most obvious on this album and Passwords.

Right at the end of our Nothing Is Wrong tour, I blew my voice out in a serious way, and I couldn’t get it back for months. When we toured Stories Don’t End, I had to relearn to sing so I could do it every night. People sometimes say, “You don’t sing ‘When My Time Comes’ like you used to.” And my response is, “I’m sorry, but this is the only way I can sing that hard and high at this point.” Even some songs from the last album … “Feed The Fire” is a fucking bitch.

What comes to mind when you go back and listen to your debut?

I was sort of waking up in the middle of that record as a lyricist. I realized lyrics were fun, and I wanted to do better. I wrote “Love Is All I Am,” “That Western Skyline” and “When My Time Comes” last. I wrote as a singer first on North Hills. Now I write as a lyricist first.

A real turning point seems to be Stories Don’t End.

It came from having my whole world blown open by Joni Mitchell. I was always a fan, but before writing Stories Don’t End, I became a nerd about every album. Court And Spark, The Hissing Of Summer Lawns, Hejira, Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter—those records where she just seems possessed. She just goes and goes and goes, and you never want her to stop. It’s almost like Dylan, but way more musical. She’s directly responsible for “From A Window Seat”—just me trying to come up with the first line and letting the song be what it is, whatever happens. “Just Beneath The Surface” and “Most People” also have lyrics that I feel pretty great about, which isn’t common for me. She showed me that even more is possible.

—Hobart Rowland