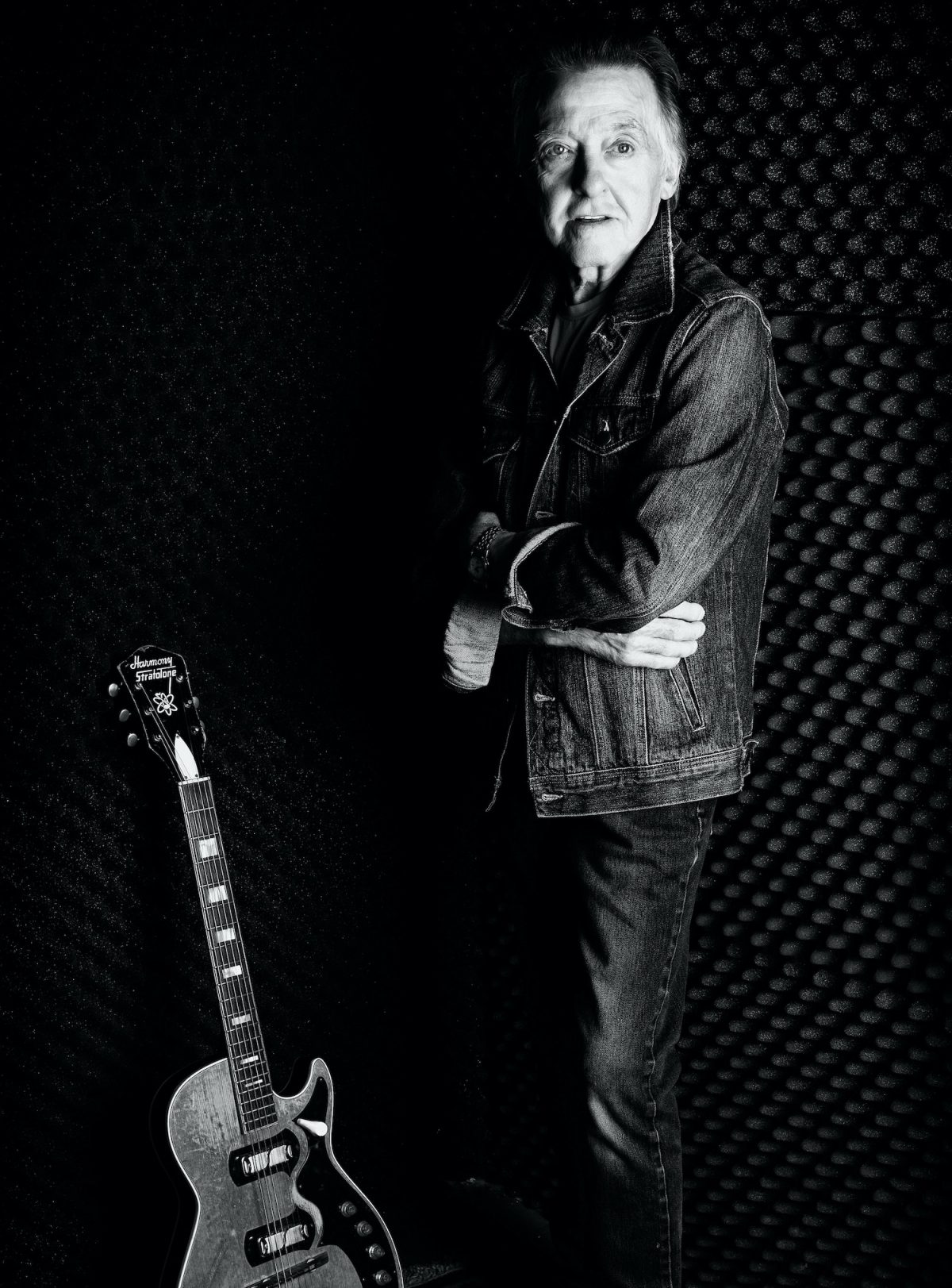

Joey Molland is the last one standing in Badfinger, a band whose horrific hard-luck story is one of rock’s great tragedies. Releasing a string of brilliant albums and singles in the early ’70s, the quartet had the support of the Beatles and their Apple label and seemed to be finding some commercial traction until the wheels came off internally. After the group was financially gutted by its manager, Molland weathered the suicides of bandleader Pete Ham and, later, bassist Tom Evans. Original drummer Mike Gibbons died in 2005.

While Ham may have been the marquee talent in Badfinger, Molland’s songwriting contributions filled out the group’s finest album, 1971’s Straight Up, and its excellent follow-up, 1974’s Wish You Were Here. Following the death of Ham in 1975, Molland stuck it out with Badfinger until 1982, when he left to pursue a solo career. Playing in various groups and as Joey Molland’s Badfinger since 1983, he most recently survived a spandexed water-gun-wielding Todd Rundgren on a Beatles’ White Album tribute tour that also included Christopher Cross, Chicago’s Jason Scheff and the Monkees’ Micky Dolenz.

Molland has just releases his fifth solo album, Be True To Yourself (Omnivore), and it features contributions from Dolenz, Scheff, Julian Lennon and Steve Holley (Wings). It’s produced with some serious backbone by journeyman Mark Hudson, who co-wrote much of the material.

MAGNET recently caught up with Molland at his home in Minneapolis. Though he’s been living in the United States for decades now, Molland’s Liverpool accent is as pronounced as ever. The same goes for his glass-half-full outlook on life.

How long have you been living in Minneapolis?

Since 1983. My first wife, Kathie—I should say my only wife, and the mother of my two children—was from here. She passed away in 2009. We came back here to raise up the children, and I’ve been here ever since.

What was it like touring with the likes of Todd Rundgren and Christopher Cross for the White Album tribute?

Well, we had the Beatles music to play around with, so it was easy to make it work. Everybody was having fun with the songs, and we could all do the job—once we got through that first couple of days, where it was a bit rough. None of us had really ever played any of the songs before. The White Album isn’t one of the most played records. The different ways the performers did the songs was really fun to watch. Micky Dolenz’s version of “I’m So Tired” was just fantastic, and Todd brought the energy every day—and, of course, I know Todd from the old days. (Rundgren produced much of Straight Up.) We were actually going to go out again this year and do some of the Abbey Road record, but it looks like we’re going to do that next year, if circumstances permit.

Your relationship with Mark Hudson has turned quite productive.

I first met him at a Beatles festival. He’s been a major recording artist and TV star all these years. He did a great job on this record, though I don’t know if it will sell. I don’t even know how to sell a record these days. I was thinking I’d try to personally push it to FM radio. [Laughs]

How did you connect Julian Lennon?

We’re not really good friends or anything, but I met him a few times. He’s a real sweetheart, and he was just a regular working guy, learning his parts and taking direction from Mark. I hope that someday we can become good friends, but he lives in Europe and I live in Minnesota, so it’s not like we’ll see each other at the store.

What about the songs on this album? When were they written?

I sent Mark like 40 songs. Some had been written yesterday, some had been written years ago. For many years, I had the melody and the chord sequence for “Be True To Yourself.” I recorded it on another album called Return To Memphis. Mark picked the others he really liked, and he said to me, “Where are the choruses?” I don’t think of songs like that. I write the song as the idea comes to me. Mark contributed a chorus to any song that he felt needed it—and he did a bloody great job of it.

We last spoke in 2000, when Badfinger biography Without You was released. You were fairly diplomatic about the book’s account at the time. Looking back, were you happy with the way it came out?

Yes and no. I know (author) Dan Matovina meant well, and he wanted to tell the story. But I don’t think he got it quite right. He made a lot of assumptions about what the band was like. But he loved Badfinger, and he obviously loved Pete Ham. Matovina asked me to contribute, but I wouldn’t. I didn’t really think he was qualified to write a book about any band. I felt a little bit demeaned by the book, actually. It was like I was responsible for all this bad stuff that happened. The book made my wife cry. She was crying about the way the story was told. We were all close friends. We all lived in the same house. Of course we had fights.

Is there still room for a more definitive Badfinger biography?

It’s certainly an interesting story. I lot of good stuff happened for us. Back in the ’90s, we were actually talking to [Murray Silver], who’d co-written the Jerry Lee Lewis book Great Balls Of Fire. He told us at the time that there wasn’t much interest in the band.

How did you keep plugging away and keep such a positive attitude after the deaths of you bandmates?

The experience of Badfinger and all the money troubles—that was a pretty normal thing for bands in those days. We didn’t know much of anything about the world, and it was still a fantastic feat to come to America. We had a great time, we made some money, and we took what we needed. We didn’t need a lot of money. Then it all got sour—1974 was really when it all came to a head, when we couldn’t get any money to buy things like tape recorders, even though we were making a lot of money. We got letters from Apple about how much money they’d paid to the managers, and like a bunch of fools, we thought the money was going into the bank. But (Badfinger manager Stan) Polley went totally mad and spent it all—not like some of it or most of it, all of it. Pete loved Polley. We wanted to leave Polley. Pete wouldn’t do it, and he actually left the band because of it.

So it must have been the ultimate betrayal when Ham finally figured it out.

The band broke up, and a few months later, Pete found out that we were right. He called Polley to get some money for his wife, who was having their child, and he couldn’t get anything. It was a nightmare. I was really shocked that he [killed himself]. And I was really angry about it. It was madness. But overall, I have really good memories of being in Badfinger. I put myself into the band 100 percent, and I really worked hard.

What was the state of Badfinger during the making of Wish You Were Here?

We’d just finished a tour, and the band was feeling good. Polley showed up at Caribou Ranch, and it was just blatant what was going on. Pete was having an affair, and that wasn’t sitting well with anybody. So it wasn’t the easiest thing. Still, we made the record, and some of the songs are really good. Chris Thomas did a fabulous job on the production side. I lot of people think it’s our best album. We had a great time going to the Rocky Mountains to make a record. We ate well, we had a couple of beers, and away we went.

—Hobart Rowland