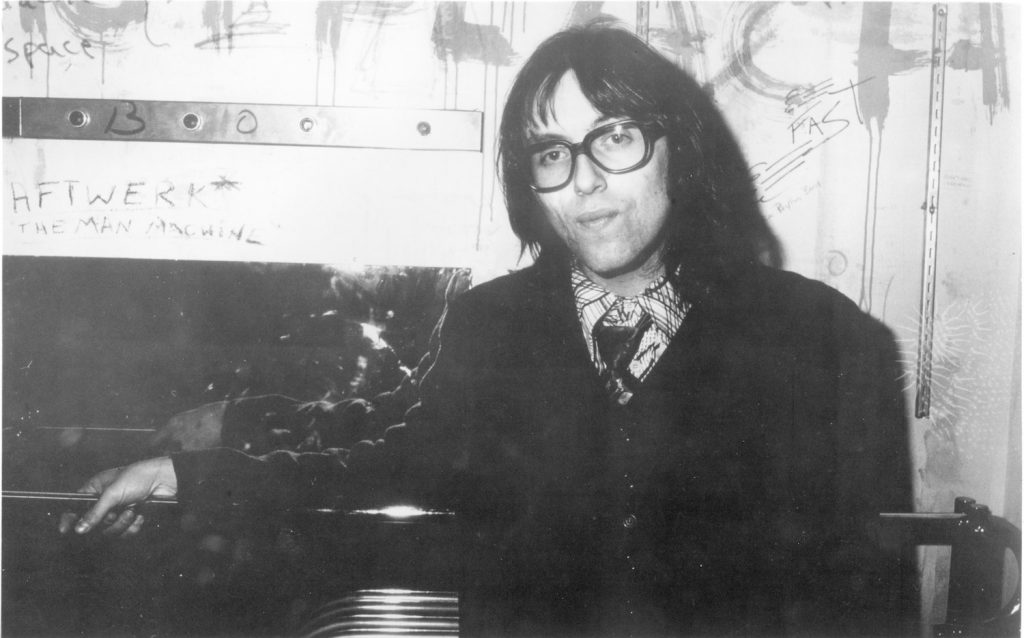

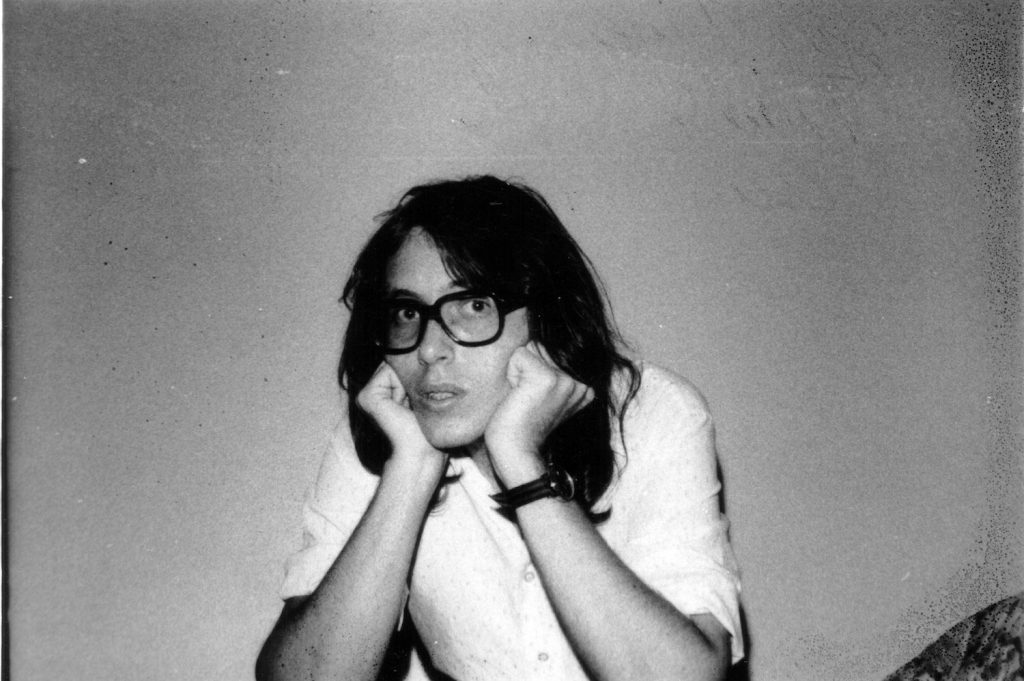

If Big Star was one of rock history’s great oversights, it’s a bit easier to understand the plight of one of their Memphis contemporaries. In 1976, Van Duren was playing with Big Star’s Chris Bell and Jody Stephens in a band called the Baker Street Regulars. Two years later, he hired Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham and released Are You Serious?, his promising solo debut. A compelling balance of sincere ballads and angular power pop, the album prompted glowing comparisons to the likes of Todd Rundgren and Paul McCartney.

What momentum Duren had achieved with his stellar debut was snuffed out when a second album was abandoned in an awkward split with his record company. In the ensuing decades, he continued to work as a musician in his hometown. And while Duren seemed resigned to his fate as a talented Memphis curiosity, a pair of overseas fans had other ideas. Somehow, Wade Jackson and Greg Carey came across Duren’s music in Australia. Suitably enthralled, they made him the subject of a 2018 documentary called Waiting: The Van Duren Story. Omnivore released the film’s soundtrack and is now set to reissue re-mastered versions of Are You Serious? and its follow-up, Idiot Optimism.

Forty years later, Van Duren has regained some of that lost momentum—and he couldn’t be happier, as MAGNET discovered in a recent interview.

What was the process of reissuing these two albums, and what was involved on your end?

We had to bake the master tapes, so I took them to Ardent Studios in Memphis and gave them to Adam Hill, who worked on all the Big Star and Chris Bell reissues. He’s an archivist and knows that process. Then they transferred everything to digital in 2017. I had a relationship with Omnivore, and I put them in touch with the documentary filmmakers, and that’s how the soundtrack ended up on Omnivore. I asked Omnivore if they’d be interested in the reissues, and the immediately said yes. They weren’t really presented in an ideal fashion all these years. Now they are.

What role did the documentary play in all of this?

In a nutshell, Trod Nossel, the studio where I recorded those albums in the late ’70s, owned the rights to the music. One of the goals of the Australian guys who made the film was to get the rights back. So they found an attorney, and we came up with a cash offer that was really ridiculously low, and they went for it. The attorney went to the studio to get them to sign off on the agreement and hand them a cashier’s check—and, lo and behold, they came out with the original tapes. The studio’s policy was to record over sessions with the next project that comes along, so imagine my shock when my attorney texted me a photo of the tapes in the back seat of his car. It was pretty emotional.

What was your mindset when you recorded your debut?

Basically, I felt it was my last shot. I bought a one-way ticket to LaGuardia and I commuted from where I was staying in Greenwich Village to Wallingford, Conn., where the studio was. I spent about two months making the album (for Big Sound Records), and then went back home to Memphis and waited until the damn thing finally came out in March of the next year. I toured all over the Northeast for about five months and had some success. We sold several thousand records—for an unknown independent label, that surprised everyone. We also got airplay on over 100 FM stations around the country. Then the tour wrapped up, and the label said they wanted a second album. I was ecstatic about that.

But things were a little different for the follow-up.

Most of it was written through the course of the recording process, which stretched out 16 months. Along the way, everybody at Trod Nossel, aside from myself and one other person, converted to Scientology. That atmosphere made it a frigging nightmare. But I was determined to get it finished. We got it mixed in January of 1980, and then I got the hell out of there. The label had come up with this new concept that the artist would go to the bank and take out a personal loan to put out the record, so I walked. I stayed up in that part of the country another year playing live and just being completely floored and depressed that the record would never see the light of day.

How do you move on from something like that?

It was really devastating. I’d put all my eggs in that particular basket, and I was really proud of it. I knew what I had with Idiot Optimism, but I new I couldn’t take that on myself because I didn’t have the rights. Just to survive, my band morphed into a cover band, and we were struggling pretty seriously. In 1981, I picked up and moved back home and started over again. I put together a band called Good Question, and we played in Memphis for 17 years. Then, in 1999, I had a stroke when I was 46 and lost my right side. I’d just finished an album with (onetime Chris Bell collaborator) Tommy Hoehn. He had hepatitis C and I’d had a stroke, so talk about a pair. As we were both recovering, we did a second album. Then I did two solo albums before I hooked up with (singer/songwriter) Vicki Loveland, and we have new music coming out soon. I kept going forward as best I could.

The documentary addresses your audition for the post-Chris Bell version of Big Star that didn’t work out. What was the full extent of your connection to the band?

When I was 16, leading a band here in Memphis, we took on a female lead singer. Her name was Beverly (Baxter Ross), and we became good friends. One night, we were finishing a rehearsal, and she needed a lift over to a college in town. Her boyfriend was playing in this band doing a sorority gig or something. We got there around midnight, and they were just wrapping up their last song, Free’s “The Stealer”—and I’m a huge Free fan. Her boyfriend was the drummer, and it was Jody Stephens. The other two guys were Andy Hummel and Chris Bell. This is before they got together with Alex (Chilton). Jody and I connected, and when the Big Star records came out, they completely blew me away. Sonically, they were so wonderful—and that was also John Fry at Ardent, of course. When Big Star was falling apart in ’74, Jody and I decided to start writing together. In ’75, we did some demos at Ardent. All the while, Chris was in and out the country working on his solo stuff. Eventually, the three of us decided to put together a band. We played live for the first half of 1976—and, once again, here you are in Memphis and you can’t make a living. So Chris went one way, Jody went back to school, and I moved forward with my stuff.

Do you still keep in touch with Jody?

Absolutely. I see him every month or two; we’re good friends. He’s a good man and absolutely one of the greatest drummers that ever was. Over the years, he just keeps playing hard and harder and harder. I don’t know how he does it. I think he has a painting in the closet that’s aging, like Dorian Gray. He hasn’t changed a bit—except his sideburns are a little gray.

—Hobart Rowland