“I’m just fine,” says Roky Erickson in response to the standard polite inquiry. This is anything but mundane stuff for the former singer of the 13th Floor Elevators, the drug-addled Texas combo credited with being the world’s first psychedelic rock band.

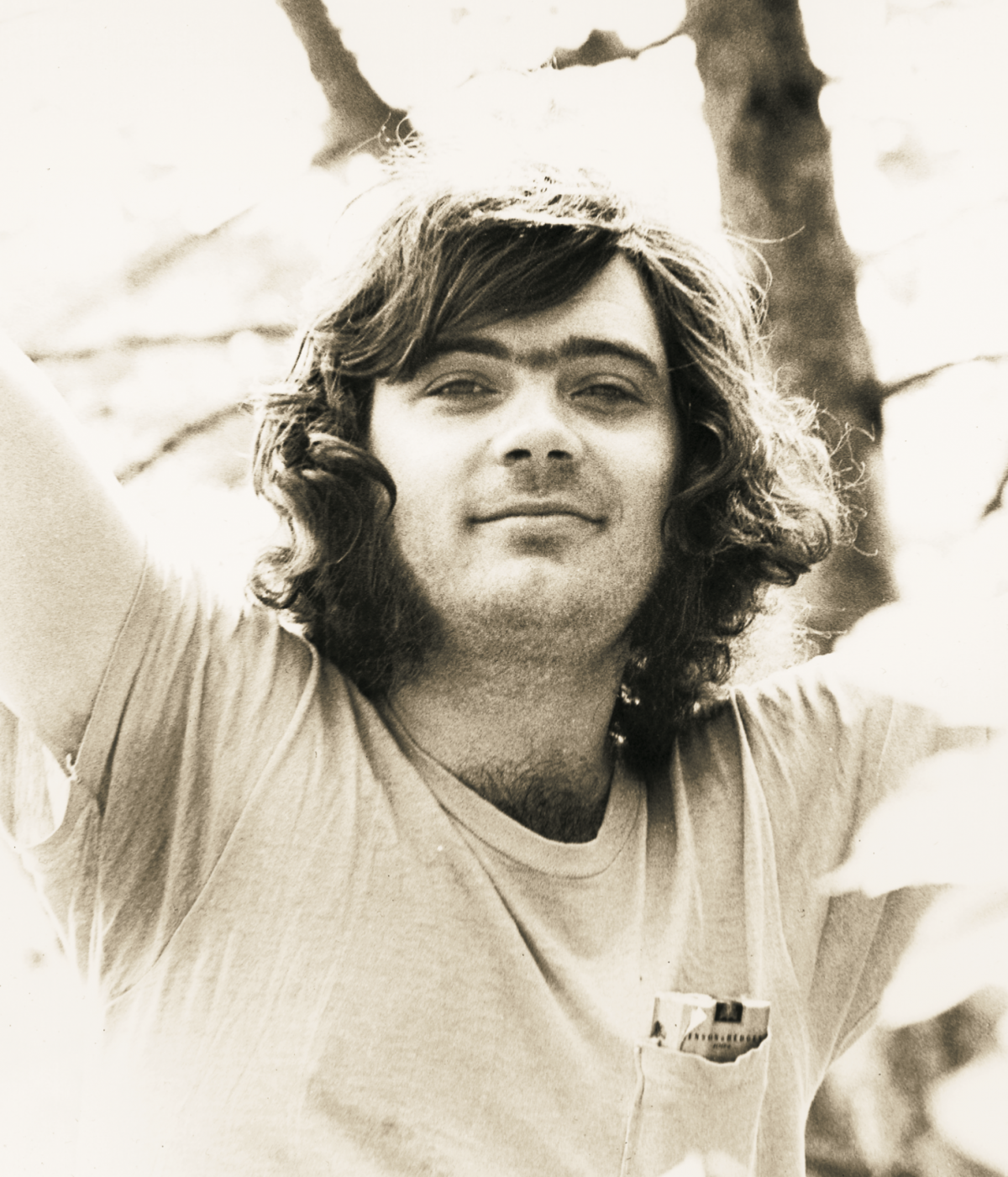

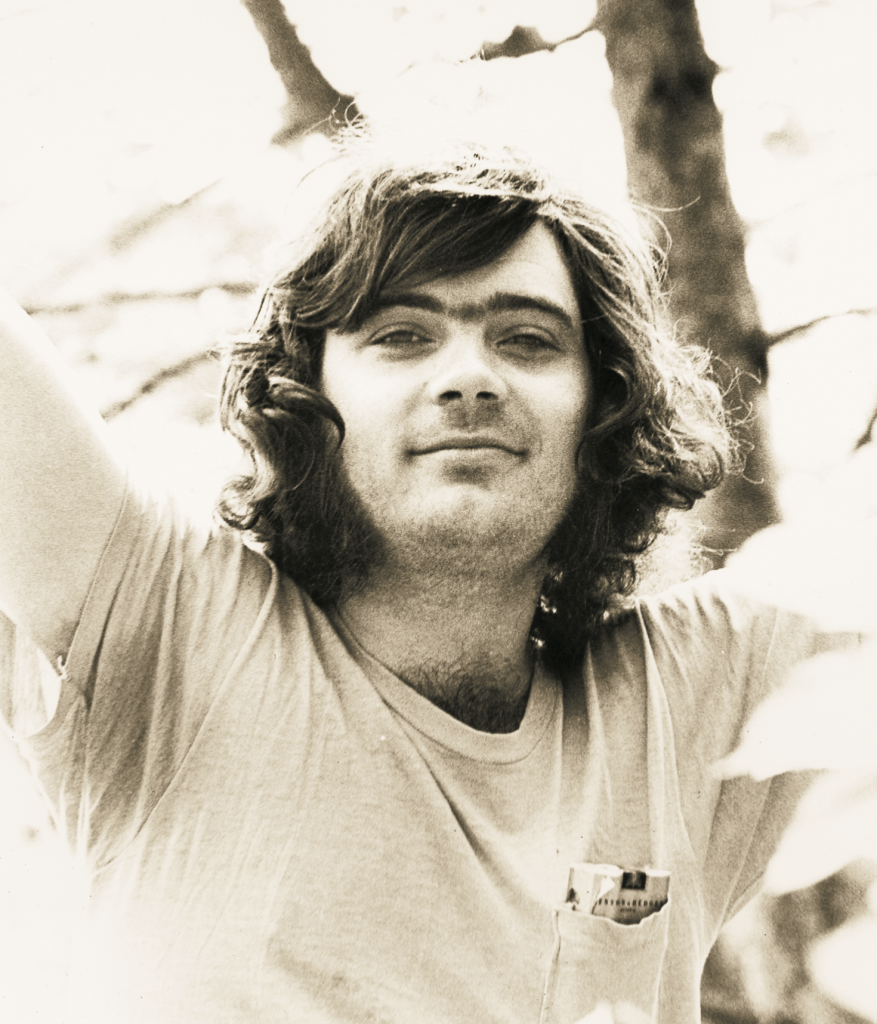

The 56-year-old Erickson, institutionalized decades ago as a paranoid schizophrenic, is back on his feet again, taking medication for his mental illness and sporting an expensive set of handmade false teeth to replace the ones that had been rotting for years. He’s also shaved off his scraggly beard, trimmed his unruly hair and recently acquired a driver’s license. “I went and passed the test the first time off,” he says proudly.

The heartwarming rehabilitation of this music legend is mainly due to the intervention of Sumner Erickson, court-appointed legal guardian of his older brother and first-chair tuba player of the Pittsburgh Symphony. “It was amazing, every little step Roky took,” says the 41-year-old Sumner, who moved his brother to Pittsburgh in 2001 to begin the 13-month reclamation project. “He’d come to the dining table, and as soon as he’d finish his food, he’d leave. Then one day, he just sat there with me and talked while I finished my meal. He’s a deeply feeling man, and I think he was embarrassed by his appearance. This is somebody who didn’t want to be touched, and now he enjoys signing autographs for fans. He saw my therapist 120 times in one year. He’s healthy and he’s happy, and it’s glorious to watch. Meet him now and you wouldn’t think that this guy must have suffered.”

Sumner relishes his childhood days when Roky would teach him how to play songs like “Secret Agent Man” on a kids’ guitar. “The Elevators rehearsed in our living room once,” he says, “and I was lying on the floor in front of one of the amps, soaking it all up. I remember Roky coming over one day, wearing these far-out, green-and-purple striped pants, and he had a little tiny pair for me.”

Named Roger Kynard Erickson after his father, Roky (pronounced “Rocky”), whose nickname is the combination of the first two letters of his first and middle names, got the bug to sing at an early age. “I listened to the radio a lot at night with the lights out,” he says. “There was this DJ named Lavada Durst who’d play rock ‘n’ roll and blues. I remember singing along to Little Richard.”

In 1965, Roky was asked by Tommy Hall and Stacy Sutherland to join a band they were assembling called the 13th Floor Elevators. “I was playing at the Jade Room in Austin with a group called the Spades,” says Roky. “They’d been listening to me sing and asked if it was possible for me to leave the Spades and come sing with them. So I told ‘em, ‘Sure I could.’” Hall’s lead role on the electric jug intrigued Roky. “Tommy was a fan of the Jim Kweskin Jug Band,” he says. “He thought it’d be a good idea if the jug played a main part.” The Elevators scored a regional hit the following summer with “You’re Gonna Miss Me,” a textbook blend of psych and garage, and parlayed the single’s success into a West Coast tour.

The apocalyptic wail of the 13th Floor Elevators—with Roky’s banshee-like vocals, Sutherland on guitar, Ronnie Leatherman on bass, John Ike Walton on drums and Hall’s throbbing electric jug (the band’s mind-altering X-factor)—was immediately embraced by San Francisco’s blossoming psychedelic community. The Elevators shared Fillmore Auditorium and Avalon Ballroom stages with Big Brother & The Holding Company (featuring Texas expat Janis Joplin), Quicksilver Messenger Service and the Great Society (Grace Slick’s pre-Jefferson Airplane band). “They always had a light show at those places, like a lava lamp spread all over the walls,” says Roky of the three glorious months the band spent at S.F.’s hippie palaces in late 1966.

“Our first night in town, we played Winterland,” chuckles Leatherman. “This dealer named Angel gave us a pound of Acapulco gold and 35 hits of Owsley’s acid. He said, ‘Welcome to San Francisco.’”

Rumors of the band’s drug excesses are well-founded. “We did every show on acid,” says Leatherman, “and all the recordings on acid, too.” Even Dick Clark was touched by the Elevators’ lysergic reputation. “When they shot our segment of (syndicated TV show) Where The Action Is next to Dick’s swimming pool in Beverly Hills,” says Leatherman, “we brought along this Texas soda pop called Iron Brew. It came in a green bottle without any label. We gave one to Dick, and he looked at it like, ‘How much acid does this have in it?’ I don’t think he tried it.”

According to Leatherman, there were no signs of Roky’s impending mental breakdown in California. “He and I were just 18, the youngest guys in the band,” he says. “And we got along real well. It was great going into restaurants with Roky because he always had a good comeback, flirting with the waitresses.”

It wasn’t until the Elevators returned to Austin that things began to unravel. The first major sign of trouble for Roky came when the Elevators, then with two LPs under their belt (1966’s The Psychedelic Sounds Of The 13th Floor Elevators and 1967’s Easter Everywhere), were scheduled to play San Antonio’s Hemisphere Arena in early ‘68. “It was a big deal, and all the family came down,” says Sumner. “Roky came out onstage, and he couldn’t continue. They told me he’d had a nervous breakdown, but I remember thinking, ‘Why can’t my brother do this show?’”

Later that year, after being convicted for possession of marijuana, Roky was committed to Rusk State Hospital, a former prison. “He had a big habit before he went to Rusk,” says Sumner, “and he had a big habit after he got out: speed, acid, and I think that he mainlined.”

Only seven at the time, Sumner himself would need therapy decades later to shake the effects of his brother’s three-year incarceration at Rusk, where they gave Roky Thorazine and administered electro-shock therapy. “Going into that place was very unpleasant,” says Sumner. “It was maximum security, with guards up in the towers— worse than jail because of the people who were in there. I remember a picture of a man holding the mic for Roky while he was playing guitar, and the guy was in there for matricide.”

Roky continued to write songs after his release from Rusk (at least 300 of them, by Sumner’s count), some wonderfully melodic, others darkly disturbing. “Starry Eyes” is a gorgeous melody with a Buddy Holly lilt to it. “Yeah, Buddy Holly was a big influence on me,” says Roky. “I just like the way he sings, real soft and easy. It’s kinda angelic, I guess you could say.” “I Am,” a song Sumner won’t listen to (“I am in Satan’s all-perfect love”), is a horse of a different color. “Roky became a preacher in Rusk,” says Sumner, “so maybe he thought, ‘Where did that get me? Why not go the other way?’ I have lyric sheets where Roky’s scratched out ‘God’ and written ‘Lucifer’ instead.”

Exciting new material was put to tape in 1979—produced by ex-Creedence Clearwater Revival bassist Stu Cook and released in 1980 as Roky Erickson And The Aliens—and was the cream of Roky’s post-Elevators crop. “I Walked With A Zombie,” “Night Of The Vampire” and “Creature With The Atom Brain,” with San Francisco combo the Aliens serving as his backing band, were ghoulishly rocking enough to appeal to punk crowds. Obsessed with trashy monster films, Roky would keep them running night and day on his TV in his Austin apartment years later. “I’ve always liked horror movies,” he says. “I used to go to the Capitol Theater in downtown Austin every weekend because they’d always have horror movies like The War Of The Worlds playing there.”

When Roky returned to Austin in late 1979 and signed up local new-wave group the Explosives for a two-year tour of duty as his backing band, he seemed perfectly normal. “In the earliest days,” says former Explosives drummer/vocalist Freddie Krc, “rehearsing in my garage, Roky was lucid, playing great guitar and singing great. No sign of any mental problems … Roky has an offbeat sense of humor. He looked at me once and said, ‘Fred, I know you think I’m a pretty terrible guy, but I’ve got the heart of a young boy. I keep it in a jar under my bed.’ We played a place called Skip Willy’s in San Antonio, and the owner told him he’d been a big fan for years. Roky looked him right in the eye and said, ‘I’m gonna see you die tonight, brother.’ And it scared the guy to death. If he’d only known that was a line from (1955 movie) Creature With The Atom Brain, everything would have been OK.”

By the second year of Roky’s alliance with the Explosives, things began to sour. “The bigger and better the gigs got, the worse his schizophrenia would take hold,” says Krc. “We were opening for the Psychedelic Furs and not putting our best foot forward. It was a combination of Roky not taking his meds and everybody around him giving him drugs. He couldn’t concentrate.”

When Roky insisted on assuming the lead-guitar role, the end was near. “He was a great rhythm-guitar player,” says Krc, “but when he played lead, the song would go on and on and on, rather than ending with a bang. It was like grabbing the reins of a runaway horse.” According to Krc, Roky would complain, “You guys don’t see my vision.” When the Explosives put their foot down about his guitar work, he countered with, “All I see is blood.” The band members decided they’d had enough. “We said, ‘OK, we’ve heard all that,’” says Krc.

Solo albums appeared sporadically from Roky during the ‘80s and early ‘90s, many of them live sets rehashing material from Roky Erickson And The Aliens. He finally re-emerged after years of inactivity, playing the Austin Music Awards show in 1993 to critical acclaim. Openers II, a book of his song lyrics, was published in 1995. Roky attempted a book signing at the Iron Works, an Austin barbecue joint, but soon ducked out, complaining of a headache after signing “ROK” in just a few copies.

The amazing transformation of Roky Erickson and his return to Austin delights Krc. “He’d turned into this person who walked around with his arms locked together, chain-smoking, not wanting to talk to anyone,” he says. “But now it’s obvious he feels safe and comfortable. We did an Elevators tribute show recently, and girls would come up and ask Roky to dance, stuff you’d never imagine he’d do. He’s everybody’s hero in Texas.”

Sumner thinks Roky will play music again when the time is right. “We dropped into a friend’s studio last summer, and Roky sat down at the piano and played a bunch of Del Shannon songs,” he says. “I videotaped him on guitar later that evening, and he seemed like he was just testing the guitar, playing some harmonics. Then he played a gorgeous rendition of ‘Can’t Help Falling In Love.’ When I watched the tape later, I realized the stuff that seemed like tinkering was really a very sophisticated introduction to the song. Roky’s a genius. If music is just like riding a bike—something you never forget how to do—then Roky is Lance Armstrong.”

—Jud Cost