Each week, we take a look at some obscure or overlooked entries in the catalogs of music’s big names. MAGNET’s Bryan Bierman focuses on an album that, for whatever reason, slipped through the cracks in favor of its more popular siblings. Whether it’s new to you or just needs a revisit, we’ll highlight the Hidden Gems that reveal the bigger picture of our favorite artists.

On Dec. 26, 1967, the Beatles’ new film Magical Mystery Tour premiered on BBC television; the next day, almost every newspaper in Britain ravaged it. The Biggest Band In The World had its first real taste of critical failure; of course, they were being a bit harsh. The consensus was that the movie was an unfocused, psychedelic mess—which it most certainly was—but that only added to its goofy charm. No matter what the critics thought of the film itself, its music was undeniably great, and the accompanying soundtrack (an EP in U.K., an LP in the U.S.) fared much better. Many thought the Beatles should get out of the movie business and stick to music. George Harrison was already at work, doing both.

Earlier that year, a budding young director named Joe Massot had hoped to talk to Harrison about composing the soundtrack to his debut film, Wonderwall. The plot centered around Oscar Collins, a middle-aged scientist played by Jack MacGowran (who had previously starred with John Lennon in How I Won The War) and his obsession with his young next door neighbor, hippie supermodel Penny Lane, played by future Serge Gainsbourg protégé Jane Birkin. It was a metaphor for a changing Britain: The stuffy, bowler-hatted era was being ushered out, in favor of the new, swinging psychedelic scene, which the Beatles had helped to create.

And like Britain, the Beatles were in a state of change themselves. On Aug. 27, 1967, while in Wales learning about Transcendental Meditation, the band received word that Brian Epstein, their manager and the glue that held them all together, had died of an accidental overdose. In just the year prior, they had: become bigger than Jesus, quit touring, changed the world with Sgt. Pepper, experimented with drugs, got married, had kids, etc. It was their most important period, when they went from pop stars to artists; from children to men. Now, for the first time, they were on their own.

The Beatles used their newfound independence by constantly trying new things, which for them, was simultaneously exciting and nerve-wrecking. So when Massot finally asked Harrison to compose the soundtrack, he was reluctant to accept, as he had never scored a film. But after the director assured Harrison, promising to use whatever music that was submitted, he signed on.

Harrison had become increasingly interested in Hinduism and Indian classical music, which he began to blend into his work with the Beatles, beginning with his groundbreaking use of the sitar on 1965’s “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown).” He had traveled to Srinagar, India, in ’66 to study with sitar master Ravi Shankar, beginning a friendship that would last until the end of his life. It was also the height of the Beatles’ psychedelic years, where experiments with drug use and new technology created all new sounds and structures. These two seemingly opposite musical, and spiritual, backgrounds were at the forefront of Harrison’s mind during this period, and for the Wonderwall soundtrack, he would use these elements to sonically replicate the movie’s own culture clash.

The recording of the album enhanced this idea. Sessions for the LP were done in two different stages and worlds; the psychedelic rock and Western elements were recorded that December in England, while the Indian pieces were recorded the next month in Bombay. Instead of playing the music himself, Harrison wrote, arranged and produced the soundtrack, although he is on a few tunes. The bulk of the music in the English sessions was performed by old friends, and fellow Liverpudlians, the Remo Four. The group knew the Beatles ever since their Cavern Club days, even sharing Epstein as their manager.

These sessions produced the zanier parts of the soundtrack: the Roy Rogers Western-like “Cowboy Music,” the rollicking ’20s piano jazz of “Drilling A Home,” and “Party Seacombe,” which is strikingly similar to “Flying” from the Magical Mystery Tour soundtrack. It also produced one of the album’s highlights, the monstrous “Ski-Ing.” Featuring Ringo Starr on drums and Eric Clapton on guitar (both using pseudonyms), the less-than-two-minute jam is a masterpiece of psych rock—one giant riff repeated over and over, ever-panning left and right, while sitars, cymbals and backward loops stack themselves among the madness. Clapton really shines here, his heavy guitar work ranking among the best that he would ever produce, with or without Cream.

After the England sessions wrapped up, and the U.K. had thoroughly lambasted the premiere of Magical Mystery Tour, Harrison flew to Bombay on January 7, to begin recording the rest of the score. He gathered up some of India’s best musicians including Aashish Khan, master of the sarod. Harrison later said that he used the recording as a “beginner’s guide” to better understand Indian classical music, and try his hand at writing ragas. Although Harrison is the sole credited songwriter, the influence of the musicians cannot be understated. Featuring instruments such as the pakhavaj, tar-shehnai, and santoor, these sounds were still alien to Western listeners, only just beginning to transfix its culture, and they perfectly suited the movie’s themes. With all the tracks recorded, Harrison returned to England (although he, along with the rest of the Beatles, would soon return for their infamous stay with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi).

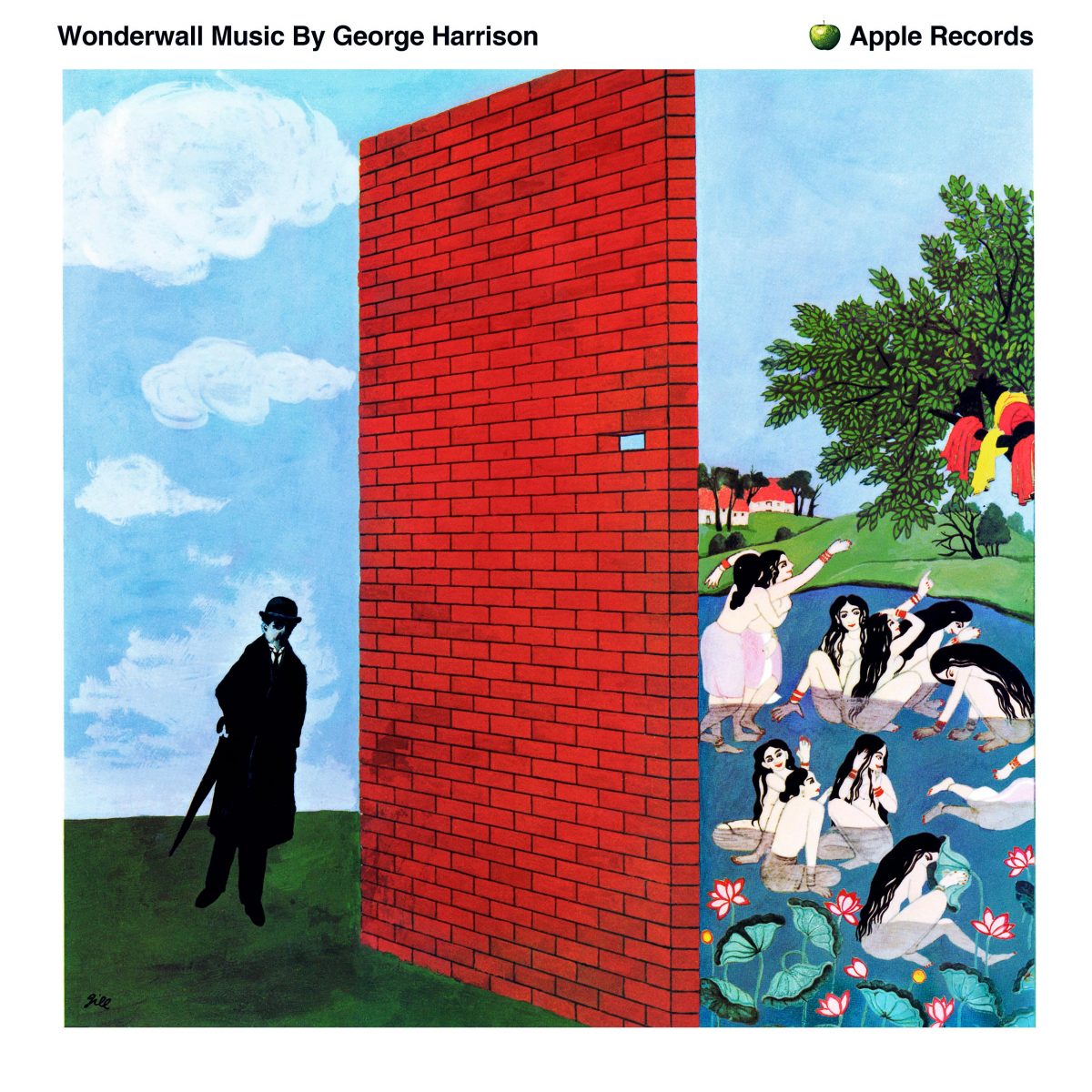

Harrison submitted his score to Massot, who was delighted, and on May 17, 1968, Wonderwall premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. The film was a head-rush of flower-power pop art and surreal dream sequences, though an entertaining portrayal of ‘60s Swinging London. That November, Wonderwall Music, was released in the U.K., the first LP on the Beatles’ Apple Records. The soundtrack was released before the film’s British premiere, ostensibly to drum up interest, but the album did not chart and thanks to mixed reviews and a poor distribution deal, the trippy art film was quickly forgotten. Curiously, Wonderwall Music reached number 49 on the U.S. charts months later, even though the film didn’t see a stateside release.

At a time when rock ‘n’ roll was changing on a daily basis, the Beatles were at the front, leading everyone into strange, uncharted depths. But with Wonderwall Music, Harrison began to venture on his own, creating fresh and unique sounds (follow-up Electronic Sounds is even more avant-garde). Now long out of print, the album has become an obscure piece of Beatles trivia instead of what it is: a fascinating experiment from one of popular music’s most interesting figures.