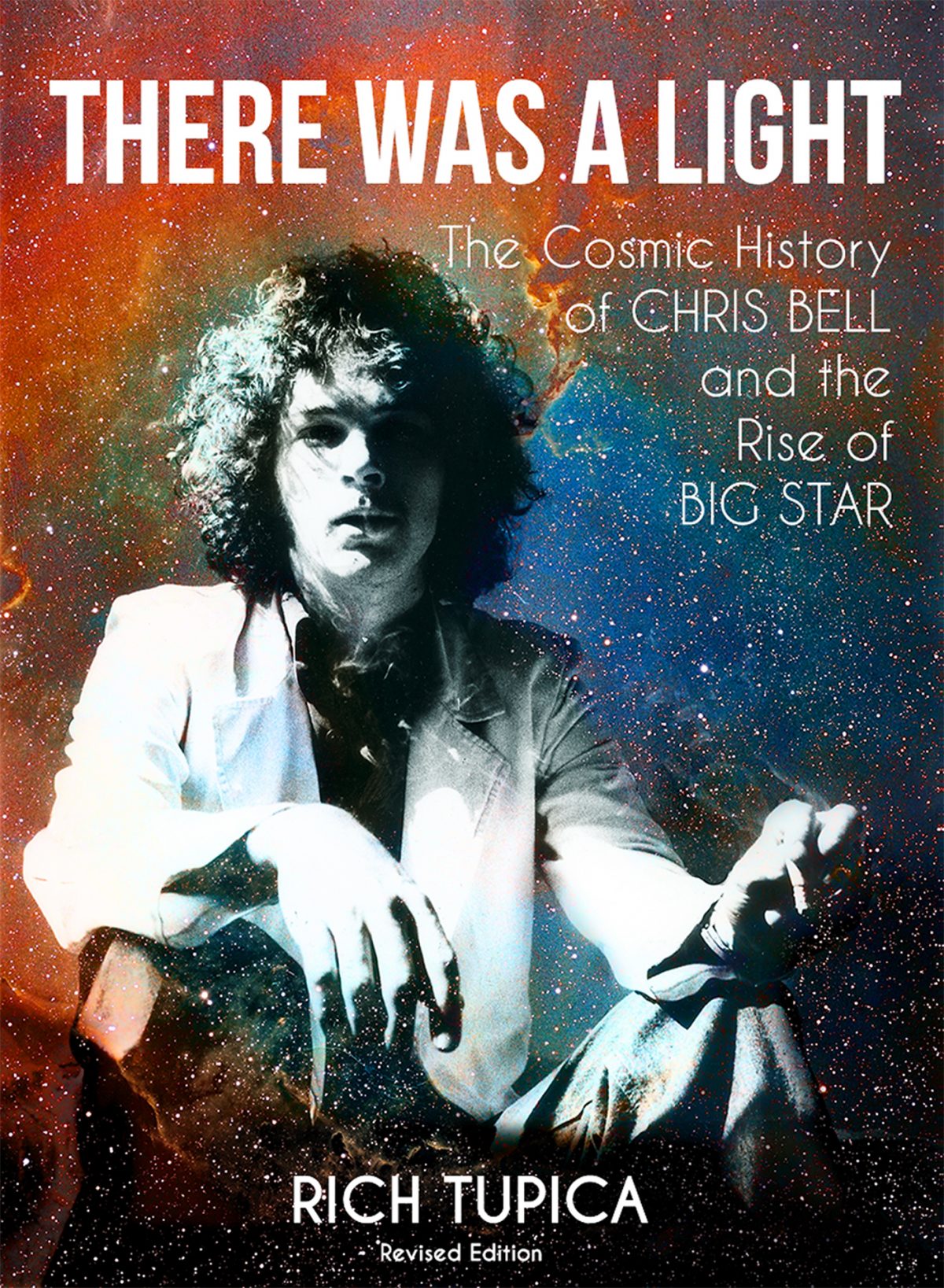

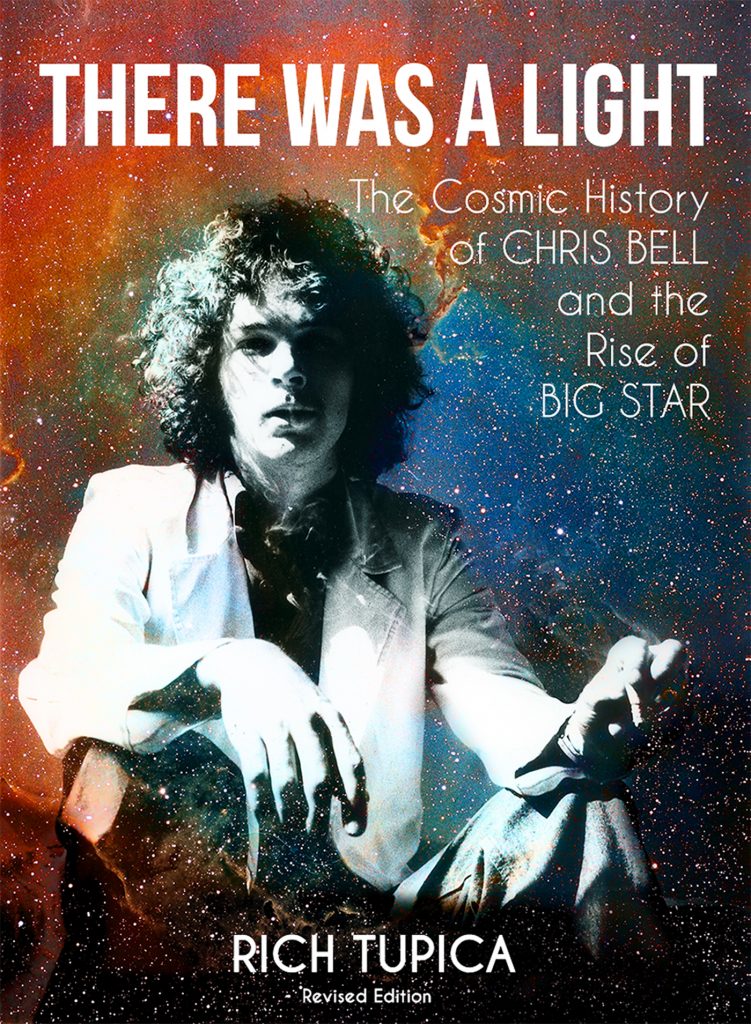

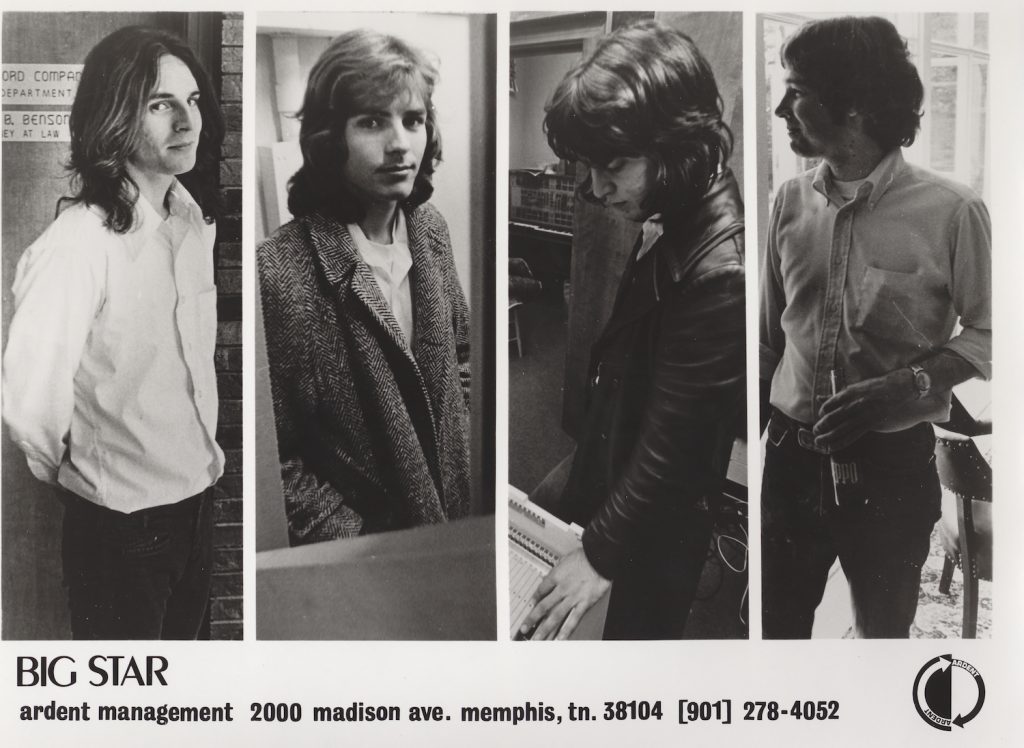

The following excerpt is from There Was A Light: The Cosmic History Of Chris Bell & The Rise Of Big Star (HoZac Books), a new oral history by Rich Tupica detailing the short life of Chris Bell, including the time he spent fronting Big Star with Alex Chilton, who’d just left his successful gig as the Box Tops’ lead vocalist.

This chapter details the days leading up to the production of Big Star’s #1 Record, the iconic power-pop band’s landmark 1972 debut LP released via Ardent/Stax. Recorded at Ardent Studios, in the band’s hometown of Memphis, the pristine record would be one of two releases Bell, the band’s founder, saw in his lifetime—the other being his signature solo single, “I Am The Cosmos” b/w “You & Your Sister,” a limited-edition 45 rpm released by Car Records just months before his fatal 1978 car wreck.

This era recounts Big Star’s genesis, when the band was still completely unknown and had never played a show, but had a batch of Bell/Chilton originals they were itching to lay down.

CHAPTER EIGHT: #1 SONGS—#1 TRACKING: 1971

As Big Star attempted to take-off, mainstream rock ’n’ roll had shifted gears. In April 1970, the Beatles broke up. Three months later Jimi Hendrix died and then Janis Joplin joined him soon after. By the summer of ’71, Jim Morrison was buried in Paris.

The radio had turned to the heavier sounds of Deep Purple and Alice Cooper. On the other side of the dial were pop hits by Three Dog Night and the Bee Gees. Still, Chris and his mates stuck to their Tennessee-tinged Brit-rock roots despite the changing trends—but it wasn’t just the radio waves shifting around the band of Memphians.

Robert Gordon—Memphis-based journalist, author, filmmaker: The wound from Dr. King’s assassination was still fresh in the early ’70s. A lot of downtown Memphis had been boarded up and never repaired, Beale Street especially. In a way, that was a time when downtown was shutting down and things were moving out east. There was white flight. Polyester was beginning to be an issue, but cotton was still king and kept the economy pretty strong. Nowadays it’s FedEx that keeps the economy strong here.

But in 1971 the local job market wasn’t much of a concern for the unwaged Big Star boys—all of whom lived with their parents during the production of their forthcoming debut.

Andy Hummel—bassist, Icewater, Rock City, Big Star: We were still getting money from our parents to survive on. It’s not like we had jobs or anything. You couldn’t be at Ardent all night and then school all day and still be gainfully employed anywhere. Alex had already made enough money that his parents put it in some sort of trust fund. He went out and bought his own car.

David Bell—brother, manager in mid-’70s: Alex wasn’t in school anywhere, but Chris and Andy were both at Southwestern at Memphis. They were university students. Music is what they were doing in all their spare time. I don’t know if Chris had a degree in mind or anything, maybe philosophy.

Jody Stephens—drummer, Icewater, Rock City, Big Star, Those Pretty Wrongs: Like the rest of the guys, I was living with my parents [at 4685 Leatherwood Avenue]. I moved out for a little while, but we weren’t making any money playing in a band. The only way you could pull that off was to live at home.

Andy Hummel: What was going on in our lives at the time was very different for all four of us and was going to create conflict. We were all coming from different directions. I was immersed in going to college. I was doing music on the side in the late evenings. Chris was still trying to go to college, he was just going part-time. He was burning the candle at both ends. Jody was going to college at Memphis State. Alex, on the other hand, was pretty much set that he was going to be a professional musician.

With much of their free time dedicated to learning Chris and Alex’s songs, the band amped up its rehearsal schedule.

Alex Chilton—singer/songwriter, guitarist, Box Tops, Big Star, Panther Burns, solo: We practiced together about three or four times a week for about three months [before recording started].

Andy Hummel: Around the time we started rehearsing, Ardent had a separate building that was going to be a studio but never was, so they let us use the building to rehearse in. We rehearsed at Alex’s parents’ house, too. We had the whole band set-up in their music room. They had a grand piano and Oriental carpet in there and we would sit in there and play. Alex’s dad was a jazz musician and he did the same thing in there.

Terry Manning—Ardent Studios producer, musician, Icewater, Rock City: I totally enjoyed hearing Big Star develop. It didn’t start out as, “This is an album called #1 Record by a group called Big Star.” A couple of tracks came from the so-called Rock City sessions, the so-called Icewater sessions, and then when Alex came in, his style and input was added to Chris’.

Steve Rhea—classmate, friend, musician, Christmas Future, Icewater: They actually didn’t pull any songs from Icewater, but they pulled “My Life Is Right” from his collaboration with Eubanks and used it on #1 Record, along with some other songs Chris had done [with Rock City].

Jody Stephens: Alex was definitely the missing piece in the band, as far as providing original songs. When he joined, the quality of songs jumped. I figured Alex would bring in a lot of experience to the stage and presence. I knew he had a great voice. Of course, the first time I heard him sing I knew it was going to be the perfect relationship.

Steve Rhea: Alex shows up and becomes the catalyst. Here’s the guy with years of road experience and a voice. When you can put writing, good musicianship and a voice together, then things begin to happen.

Chris Bell: Most of [the songs on #1 Record], except for, say, four songs, had accumulated over the past two years. “Try Again” and “My Life Is Right” I had recorded before Big Star. I had done the tracks with Jody and Tom Eubanks, who wrote half of “My Life Is Right.” I did “Try Again” all by myself, I guess. They were pretty much recorded and ready to go. Alex overdubbed a harmony on both of those songs, a little bit of acoustic work for both, and a little slide guitar on “Try Again.”

Alex Chilton: Chris and I would have some writing sessions every now and then. He came to my parents’ house and had this song that later become “Feel” … It’s mostly his tune and I just added one little line on top of his musical structure and that’s pretty much the way it went. I would turn up with something I had, and he would make a change or two or give me a line or two or three.

I feel like I’m dying

I’m never gonna live again

You just ain’t been trying

It’s getting very near the end

—Chris Bell, “Feel”

Chris Bell—singer/songwriter, guitarist, the Jynx, Christmas Future, Icewater, Rock City, Big Star, solo, engineer: I would suggest a few things and changes to Alex’s and he would similarly add to mine, but really the songwriting was a separate thing.

Steve Rhea: Chris had a tremendous influence on what Alex was doing guitar-wise, but Alex was always the better songwriter of the two and had all those years of playing in front of a live audience—that came across.

Andy Hummel: We played [the songs] together to learn them and develop the bass, drum and other parts. The songs were tweaked a bit during this process but for the most part they were a done deal when they were brought into the studio. I don’t know a whole lot about Chris’ writing technique at this point other than he was a guitarist first and foremost.

Ric Menck—fan, drummer, musician, Matthew Sweet, Velvet Crush: On #1 Record Chris and Alex’s songwriting meshes together beautifully. It’s difficult to discern where one leaves off and the other begins. The real difference is with the lyrics. Chris’ words are so damn melancholy.

Alex Chilton: I learned to write all these confused, nonsensical lyrics from Chris and Andy.

Jody Stephens: I was never a part of the songwriting process for the first record. Songs would come in and I don’t remember witnessing much collaboration, but I’m sure they kind of worked through things. With #1 Record, there was thought that went behind the guitar parts for Alex and Chris—they aren’t standard strumming parts. They were particular about guitar sounds complementing each other, not being the same but adding some sort of dimension.

Andy Hummel: My perception of those days, these days, is that Chris and Alex were musical geniuses.

While Andy is only credited as a songwriter on one #1 Record track, “The India Song,” his John Entwistle-inspired basslines seamlessly melded with the original compositions. The Bell/Chilton artistic alliance also motivated Jody, whose signature fills and drumbeats further shaped the Big Star sound. An Ardent Records press release talked up his percussive contributions:

“Jody is tall … and reminiscent of an English Teddy Boy. He plays drums with Big Star—not speedy Keith Moon stuff, but more tastefully simple things … Jody never takes drum solos or hides himself behind useless banks of cymbals and skins. While most Memphis drummers were trying to emulate Three Dog funk, Jody developed his own simple, driving beat providing a perfect basis for Big Star’s music.”

Jody Stephens: What I loved about the band was that I thought the songs were incredible. I didn’t write them—I’m not bragging. It just blew me away. I was a huge Beatles freak and I thought, “If I could ever find a band with great songs like that, I would be the luckiest person in the world.” Suddenly, here I am in this band and these amazing songs are coming out. It makes the drumming easy … I can remember the first time we did [“The Ballad Of El Goodo”]. Alex probably played through it once and I had the part the first time through on drums. It sounds corny, but it was a spiritual experience, because the part was just there as if I had heard it all before. A lot of songs were like that.

Years ago, my heart was set to live, oh

But I’ve been trying hard against unbelievable odds

It gets so hard in times like now to hold on

The guns they wait to be stuck by

At my side is God

—Alex Chilton, “Ballad Of El Goodo”

Alex Chilton: I just sort of did what the original concept of their band was. I tried to present things that were compatible with the concept they already had in place. When I say “they,” I guess I’m really referring to Chris. I just tried to get with Chris’ stylistic approach as well as I could.

Drew DeNicola—film director, Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me: It was Chris’ band that Alex joined. Chris was very conscious about who was going to be in the band and what the songs were going to be. It was a concept band he came up with in his dreams.

Alex Chilton: They were oriented toward mid-’60s British Invasion music. The way I saw it, the group was sort of designed to play that kind of music, which left out a lot of things I liked and liked to do. Being a member of a group, you abide by the rules of the group or you quit. For me, there was a lot of jazz music and a lot of black music that I love—those two categories were pretty much left out of Big Star.

The band was not Alex’s absolute vision, but these sessions produced “In The Street,” one of his best-known and most profitable compositions, thanks to its use as the TV theme for That ’70s Show, which aired from 1998 to 2006.

Alex Chilton: “In The Street” is another example of one of the best songs I’ve ever written.

Andy Hummel: Most of the songs [on #1 Record] were sung by the person who wrote it, except “In The Street,” which was completely written by Alex but sung by Chris.

Alex Chilton: That was all mine. I guess there’s a melody part that Chris sort of did. The way I had put it together, the melody is a little different than what he eventually sang. What he sang was better.

Hanging out, down the street

The same old thing we did last week

Not a thing to do

But talk to you

Steal your car, and bring it down

Pick me up, we’ll drive around

Wish we had a joint so bad

—Alex Chilton, “In The Street”

Steve Rhea: Andy has described the vocals on “In The Street” as this high, Robert Plant-type sound. When they recorded “In The Street” he capoed up on, like, the fifth fret. Alex, when he played it live later on, had no capo at all. It was a completely different key because he couldn’t sing that high—but Chris was going for the rafters. “Try Again” was more like the Chris speaking voice. It wasn’t a great voice, but it was real. That’s what people appreciate about Chris, you can feel all the pain, conflicts.

Andy Hummel: Chris liked having someone like Alex who could sing that well. I always felt that was something Chris struggled with a lot. It got better as the years went along. Alex had a wonderful, resonate singing voice you can cast in many ways. Even then, at that early age, he was amazing with it. You just didn’t hear Alex hit notes that weren’t on, and Chris appreciated that. On the other hand, Chris was a superb guitar player.

Chris’ powerful guitar riffs no doubt add the high-octane rock to Big Star’s debut, but it’s Alex’s nostalgic teenage-love ballad, “Thirteen,” that’s been covered numerous times over the years by the likes of Garbage, Albert Hammond Jr., the late Elliott Smith, and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs.

Won’t you let me walk you home from school

Won’t you let me meet you at the pool

Maybe Friday I can

Get tickets for the dance

And I’ll take you

—Alex Chilton, “Thirteen”

Carole Ruleman Manning—friend, photographer, Ardent Studios art designer: I like “Thirteen.” I don’t think it was written about anyone in particular. I knew some of the girls Alex dated around that age, including me, and I don’t think any of them got walked home from school.

Alex Chilton: On looking back at that album, I realized something about my own personal development. I had quit the Box Tops, so here I was travelling across the country surrounded by all these businessmen and older influences. I had left my own peer group completely, and in a way I never really advanced past that. What I was writing about on Big Star albums was just going back and trying to catch myself up. I was 21 at the time, but I was writing like I was sixteen or seventeen.

Andria Lisle—Memphis-based journalist: Memphis shows through lyrically in songs like “Thirteen” and “In The Street.” They paint an excellent picture of teenage life in the provincial South.

Alex Chilton: I remember making up a solo in the studio for “Thirteen” in about fifteen minutes, which is a wild bit of playing. But I was a crummy songwriter, or adept at most. Although, my dad, who was a jazz pianist, taught me a lot about musical theory when I was growing up.

Matthew Sweet—fan, singer/songwriter, musician: A thing that’s very influential to me as a songwriter was the personal nature of Big Star’s lyrics. They were personal in a “my feelings” and “me and you” way. On #1 Record they have a great understanding of sadness and innocence. There’s also this feeling of hope and capability in the record. There’s a sense of spirituality. There is a sense of hope and purpose.

Alex Chilton: If you’re writing anything decent, it’s in you, it’s your spirit coming out. If it’s not an expression of how a person genuinely feels, then it’s generally not a good song done with any conviction.

While Alex arrived with songs he wholly wrote, the credits on “My Life Is Right” had some red tape. As the album’s production wore on, Chris reached out to his friend and co-writer with a request.

Tom Eubanks—friend, vocalist, bassist, guitarist, songwriter, Rock City: Big Star’s version of “My Life Is Right” on #1 Record is the exact recording from Rock City sessions. Alex or Chris just added a few acoustic-guitar runs, which I thought emasculated the tune. I am playing bass on “My Life Is Right” on Big Star’s #1 Record. Terry Manning is playing piano. Chris, Terry and I are still on background vocals. The Rock City album was cut on an eight-track machine and there were some mix-downs that made it impossible to undo the tune, plus Chris and Alex did not care to re-record it. Listen to Terry’s piano on the Rock City version and the Big Star version—it’s the same track remixed for Big Star.

One morning while they were working on #1 Record, Chris calls and says, “We want to use ‘My Life Is Right’ on the Big Star record and we would like to show Alex as the co-writer.” He asked me if they could not list my name as a co-writer. It didn’t make me mad that Chris asked me to do this. It kind of hurt my feelings, but I understood why he asked. Chris, as I did, had an infatuation with the Beatles. Did you ever see a Beatles song where John Lennon co-wrote with somebody other than Paul? He wanted it to look like a Beatles record listing “Bell-Chilton,” with the odd song written by Hummel. It wasn’t a mean-spirited thing by Chris—it was about appearances.

Alex Chilton: It was Chris’ idea that we share credit on the tunes, although they were all written pretty much independently.

Tom Eubanks: I told Chris, “No, if you don’t want my name on the record, don’t use the song.” He said, “Well, you’ll get all the money.” I told him, “That’s not the reason I do it. And remember, you didn’t have the beginnings of the song. I did. There wouldn’t be ‘My Life Is Right’ without me.” I would not agree to that, so it’s credited as “Bell-Eubanks.”

Alex Chilton: Certainly, [Chris and I] idolized the Beatles and would have loved to do something as great as what they were doing. Our collaboration, in a way, was kind of like Lennon and McCartney, in that one or the other wrote those songs and the other one maybe threw in the smallest something, if anything at all—although we shared credit for all of them. We worked well together as musicians and both of us were serious about what we were doing … We had a lot of people in our immediate environment telling us how lame we were, but I didn’t care about that. We were doing what we enjoyed.

Jody Stephens: It was out of fashion at the time. It was a pretty raw approach to performing. Even the first record, the performances weren’t slick performances. It was a little out of keeping with the other things that were in the market at the time. We weren’t sophisticated players. Musically or stylistically, we were out of step with what was going on.

Drew DeNicola: Alex said he stopped listening to new music in 1971. He said rock ’n’ roll died for him with Led Zeppelin, which is ironic because Chris loved Led Zeppelin.

Andy Hummel: To me, Led Zeppelin was an obvious influence on Chris, especially Jimmy Page. You just have to listen to the right Led Zeppelin. Whenever I listen to Big Star that Chris played on, the Jimmy Page influence was just huge. People always think of Page as the first heavy-metal guitar player and loud electric riffs, but Page’s acoustic playing is without equal—that’s the kind of sound I’m talking about.

Bob Mehr—Memphis-based journalist, author, Trouble Boys: The True Story Of The Replacements: It’s interesting that Chris loved Led Zeppelin and could peel off Jimmy Page licks. That and he listened to studio playback at epically loud, eardrum-shattering levels. That he could be bossy and demanding when it came to his music. Sometimes, because of the sensitive nature of some of his songs, and the beautifully hurt quality to his voice, we think of Chris as this fragile, timid figure. But Chris Bell’s music wasn’t twee at all, and as a personality, when it came to his art, he was anything but shy or retiring. Chris had a commanding, boisterous side to his personality, something that existed alongside the searching, uncertain part of him as well.

Adam Hill—engineer, producer, Big Star archivist: The Beatles were the pivot point, but Big Star was listening to the Move, the Kinks, the Who, and Clapton. They had a subscription to NME. I was surprised none of them talked about Badfinger, I guess they were more contemporaries than descendants. They name-checked Todd Rundgren more than Badfinger.

Jody Stephens: We loved Badfinger. Procol Harum, I love. I don’t know if it’s reflected on anything, but their drummer B.J. Wilson was awesome. [Stax session drummer] Al Jackson was a big one for me—listen to “My Life Is Right” and then “Try A Little Tenderness.”

Along with Big Star, the Raspberries became known as a pioneering power-pop band, though Chris said his band was far from an Eric Carmen mimic.

Chris Bell: We never attempted to sound like the Raspberries. They were alright, but Big Star were always more original. I’ve loved English rock since “I Want To Hold Your Hand,” “I Can’t Explain,” and “Night Of Fear.” The Yardbirds and Roy Wood were major inspirations. Alex is more into Brian Wilson and early Todd Rundgren, the music was a blend of two channels.

Alex Chilton: I was very into Todd Rundgren when we cut that first album. I was also still listening to a lot of bluegrass and getting into bizarre things.

Andy Hummel: I loved the Carpenters and Chris did, too. He thought they were neat.

Jody Stephens: Chris added a real pop aspect to the band.

Tom Eubanks: I never heard Chris mention the Byrds. To me, with Big Star, the Byrds were an influence with Alex’s voice. If you listen to some of #1 Record it almost sounds like he’s doing Roger McGuinn.

Alex Chilton: The Byrds’ [influence] came more from me, as I was learning some country-guitar styles at that time and was listening to a lot of Gram Parsons and Flying Burrito Brothers. You transpose a country acoustic-guitar style to electric and you’ve got the Byrds.

The Byrds and Burrito Brothers may have provided stimulus, but the Big Star boys brought their personal spins into the mix, especially lyrically.

Steve Rhea: The subject matter of “El Goodo” didn’t sound brand spanking new to me because it was all flowing from our general discussion about the Vietnam War, being drafted, the fact that we didn’t want to go, and ways to get out of it. Alex put great chords to it. He gave it a Roger McGuinn-style vocal with Chris’ high harmony soaring in over that. It was a knockout sound.

Drew DeNicola: On #1 Record there are no novelty songs that are not directly related to their lives, aside from Andy’s “India Song.” It’s sort of like how the Beatles have “Taxman” or “Paperback Writer.” I don’t even think there’s a song telling a story about someone else, it’s pretty much always first-person.

After four months of rehearsals, the band started tracking at Ardent Studios, which—for the time being—was still at its National Street location. Concurrently, a brand-new building for Ardent Studios was under construction on Madison Avenue.

Chris Bell: We worked on it for about a year, aside from what I had done before we started. We started in the summer, around August of 1971.

Andy Hummel: We got our own, full-blown private reel of tape. We had just been using scraps up until then … Having access to a recording studio at that age was just like heaven. We loved it. We went into the studio whenever we could.

Terry Manning: #1 Record was a highly-crafted record over a long period. It wasn’t just jumping in the studio and throwing it together. There were many overdubs, many changes.

Alex Chilton: I learned about working in a recording studio. Before that, I had been in a recording studio and sung a lot, but I never really had my hands on all the controls or the making of the sounds in the studio.

Andy Hummel: When we first started, we just had the eight-track recorder. Somewhere in there, Fry got his first sixteen-track. We had the old console, but he replaced that with a new Spectra Sonics console.

John Fry—Ardent Studios founder, engineer, producer, Big Star: We thought we had a lot with a four-track in 1966, but by early 1967 it was eight-track, and by 1970, it was sixteen-track. It changed rapidly.

Chris Bell: We started rehearsals and started doing some tracks. I asked John Fry if he would like to engineer for us and he agreed.

John Fry: I was there for a good deal of the first record. I would usually cut the basic tracks. They would set up as a four-piece band and cut the basic rhythm track. They would normally do most of the overdubs on their own, unless something was a little complicated, then I would do it. I would do all the final mixes.

Jody Stephens: Once we began working together, I was intimidated by [Fry’s] dead seriousness. Ardent existed because of him. He was the provider, the reason we were able to be creative. Alex and Chris had a vision, which we were able to pursue without reins or over-the-shoulder guidance. Maybe we could have done the same thing at another studio, but Fry’s behind-the-board skills were sonically unique. He made Big Star sparkle.

Andy Hummel: What things John Fry didn’t personally take care of, Chris was very competent to fill in the gaps.

Alex Chilton: We felt like we could do it ourselves. We didn’t want anyone else to mess it up.

Andy Hummel: Chris was in charge. I would pretty well credit him with recording and producing that LP. Of course, he had a lot of artistic help from Alex, but Chris was the technical brains behind it. He was the only one of us at that time who knew how to record. I engineered a little of the later #1 Record stuff, but Chris was the main force.