Almost 50 years after Lou Reed unleashed white-noise opus Metal Machine Music, people are still debating whether it’s brilliant art or simply the worst album ever made. We revisit Mitch Myers’ classic feature on one of the rock era’s most polarizing records.

In the past few decades, Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music has been scrupulously analyzed by scores of pop-culture vultures who have delighted in picking apart what may be the most infamous rock ‘n’ roll swindle of all time. Almost everything seems to have been already said about Metal Machine Music. From serious analyses to not-so-serious prose, the facts, myths, quotes, lies, half-truths, accusations and discussions devoted to this radical piece of work have amounted to a huge pile of rubbish.

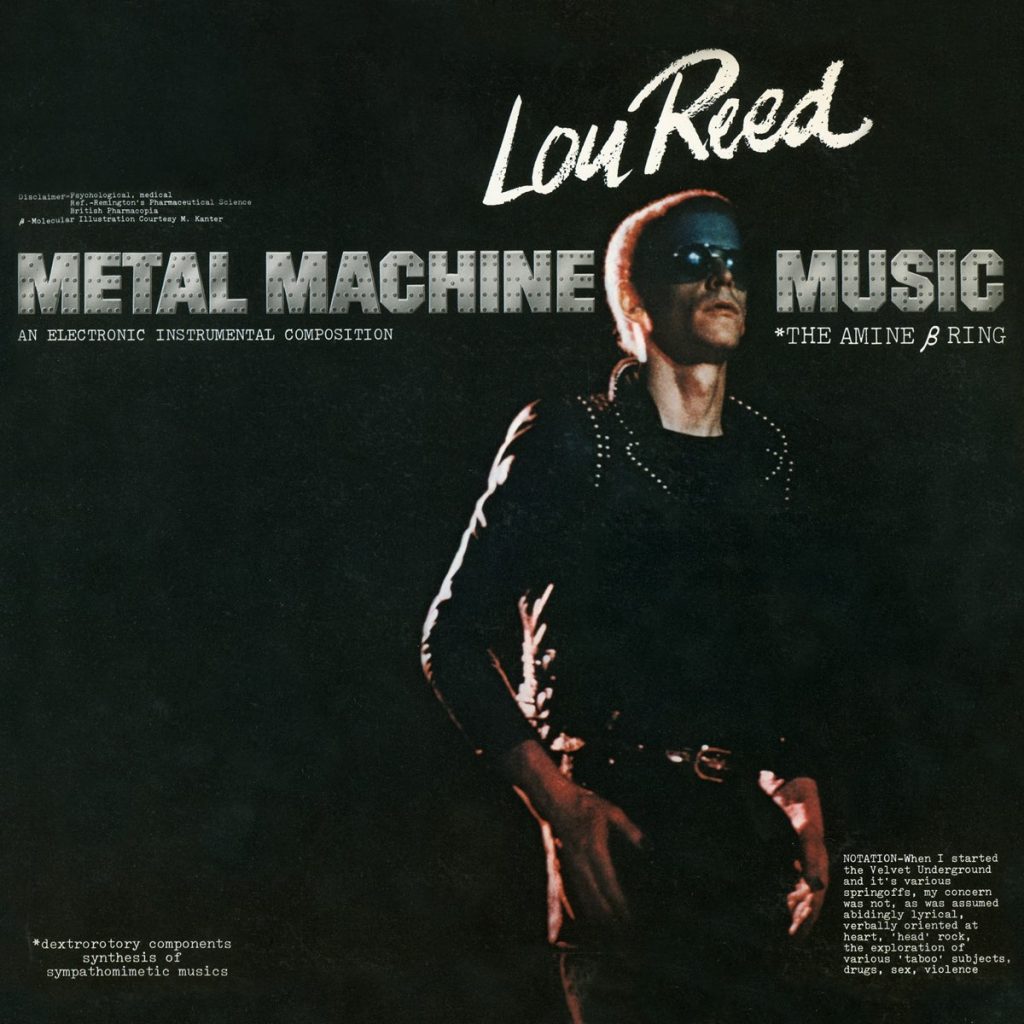

Consider these disparate bits: 1975’s Metal Machine Music was Reed’s seventh solo release after leaving the Velvet Underground. It was also his first double LP, which affirmed RCA Records’ faith in the marketability of its most notorious recording artist. Recorded in Reed’s Long Island studio near Pilgrim State Hospital, his magnum opus was formed without conventional instrumentation. Rather than using standard musical instruments or the human voice, Reed chose to stack multiple combinations of reverberating electronic sound, creating a vast, industrial howl. Derived from a process of manipulating aural frequencies and distorting both the intensity and pitch, Reed’s mechanized drones and harmonic buildups released shifting waves of pulsing white noise and emitted squeals of pure feedback into two separate, but equal, stereo channels.

On the album’s back cover—above an incorrect chemical diagram of an amphetamine concoction—a specifications list included such things as ring modulators, tremolo units, high-filter microphones and Jimi Hendrix’s Arbitor distortion box. “No Synthesizers No Arp No Instruments?” the list concluded, “No Panning No Phasing No.” In many ways, that last, lone “No” betrayed the true underpinning of Metal Machine Music’s original concept.

Representing a diametric shift away from his then-popular musical identity as the androgynous rock ‘n’ roll poet laureate of Manhattan’s mean streets, Reed’s oppositional soundscape couldn’t have been anticipated, even as an extension of the feedback/noise/distortion found within groundbreaking Velvet Underground songs like “Sister Ray.” This new music, Reed contended, was “the perfect soundtrack to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.” He also claimed to have inserted tiny snippets of classical music into the mix and that many of the frequencies were dangerous, and even illegal, to put on a record. While today’s generation of ambient/environmental/electro-acoustic drone mavens were still learning to crawl, Reed had already employed the studio as an instrument, resulting in an imposing soundtrack of electronic doom.

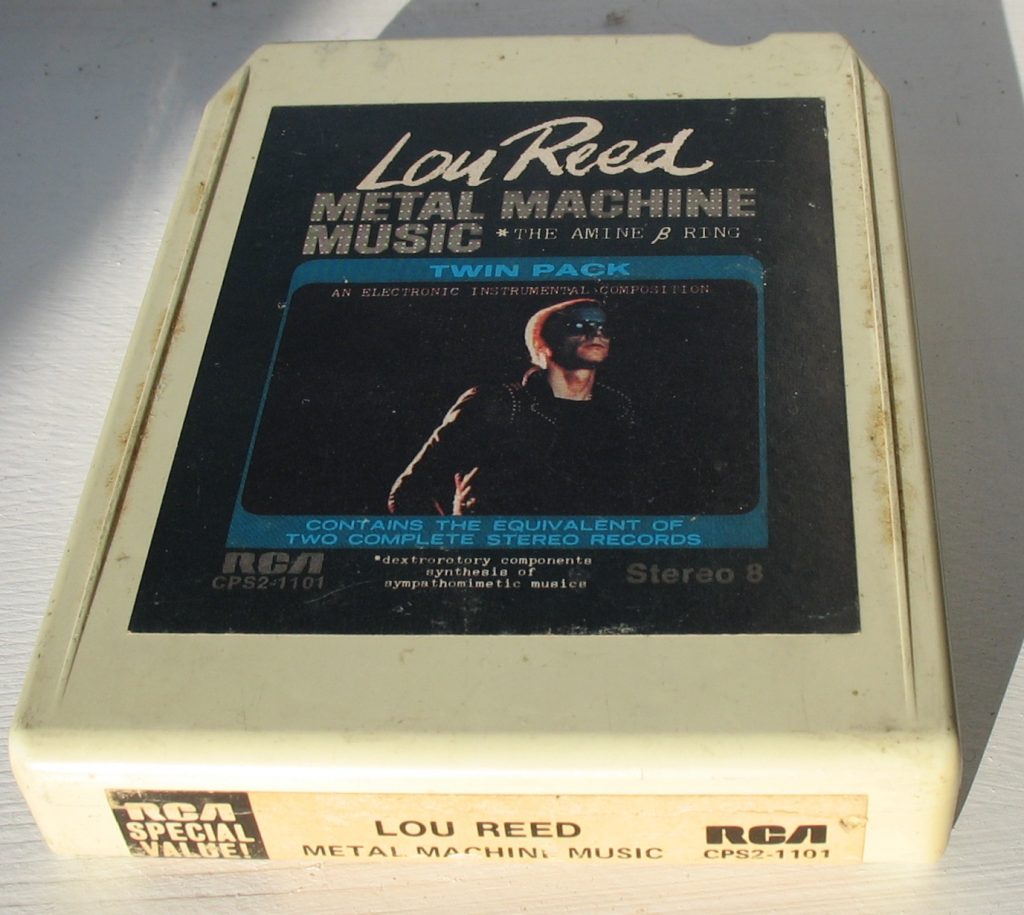

In interviews, Reed compared his unusual effort to those by avant-garde composers La Monte Young (whose name he misspelled on the back cover) and Iannis Xenakis. Although his VU bandmate John Cale worked extensively with Young and Tony Conrad in their Dream Syndicate prior to and during his involvement in the Velvet Underground, Reed never really associated with the heady bunch of Manhattan drone-art-conceptualists during the Syndicate’s speed-inspired marathons of minimal music making. Still, Reed claimed he had been working on Metal Machine Music for six years and began discussing the esoteric sound maze in several major music magazines. While this was a huge artistic gamble for Reed, RCA backed him to the hilt by issuing the recording on both stereo and quadraphonic vinyl as well as eight-track tape.

Of course, none of these efforts prevented the release from becoming a complete commercial disaster. While Metal Machine Music was reputed to have initially sold 100,000 copies, it was also reportedly the most returned album in RCA’s history. In a frantic effort at damage control, RCA pulled Metal Machine Music from store shelves and rerouted it straight into the cutout bins. Looking to stem additional loss, RCA canceled the album’s release in England altogether. Since then, Metal Machine Music (subtitled An Electronic Instrumental Composition: The Amine ß Ring) has become one of the most sought after eight-tracks of all time, right up there with vintage sound oddities like Yoko Ono’s Fly.

It shouldn’t be forgotten that late rock critic Lester Bangs waxed poetically, prolifically and prophetically on MMM. In his classic Creem article “The Greatest Album Ever Made” (later immortalized in posthumous collection Psychotic Reactions And Carburetor Dung), Bangs provided 17 lively reasons why MMM was superior to his second choice, Kiss’ Alive!. Bangs and Reed jousted brutally when discussing MMM, most of which was dramatically documented in another brilliant essay, “How To Succeed In Torture Without Really Trying.” Yet Rolling Stone voted MMM the worst album of the year. Billboard said simply, “Recommended Cuts: None.” MMM was totally panned by most critics, although Robert Christgau was merciful in his Consumer Guide, giving it an almost-respectable C+ grade. In The Trouser Press Record Guide, Ira Robbins described “the truly deviant Metal Machine Music” as “four sides of unlistenable noise (a description, not a value judgment) that angered and disappointed all but the most devout Reed fans.”

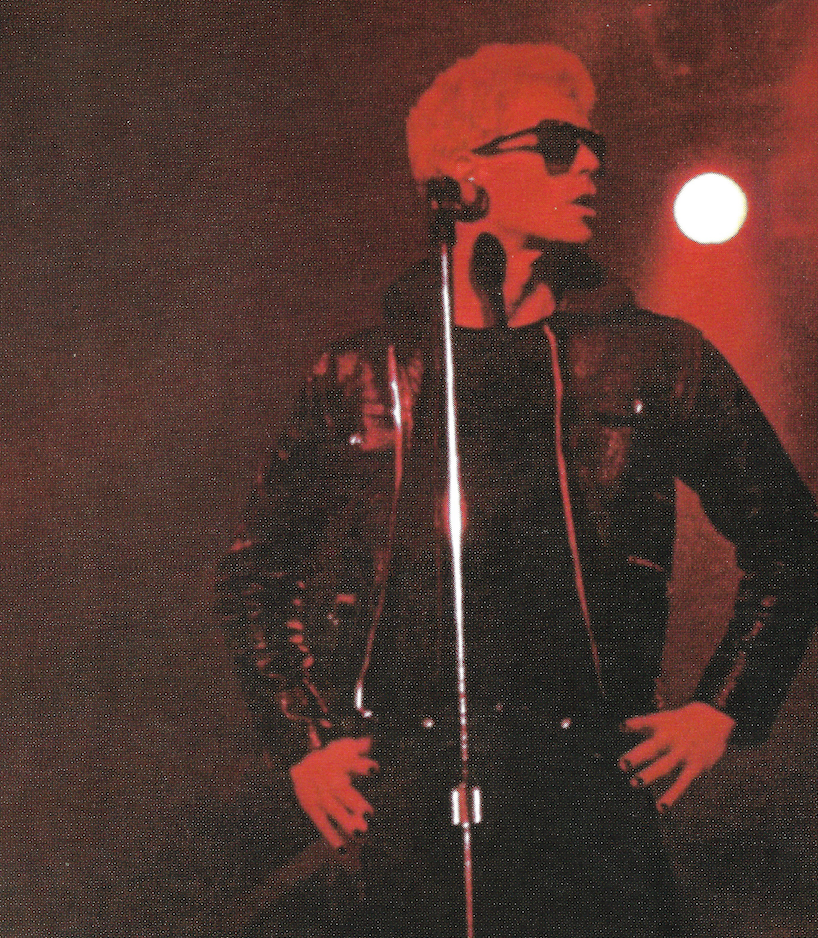

Often characterized as a scam that simultaneously enacted revenge on Reed’s manager, fulfilled a commitment for product to RCA and eliminated a growing congregation of less-than-sophisticated admirers, MMM was guilty of deceptive packaging. The album cover featured a leather-clad Reed wearing sunglasses, hair peroxide blond and looking every bit the decadent glamhead. Indeed, this image was similar to the punk icon who first captured the imagination of America’s record-buying youth with “Walk On The Wild Side” and then went in for the kill via the twin-guitar pyrotechnics of live album Rock ‘N’ Roll Animal.

Imagine teenagers all over the country rushing home with their brand-new Lou Reed album, only to conclude that something had gone terribly wrong with their stereo systems or, worse yet, Reed had ripped them off with a bunch of irreverent noise. John Holmstrom, the former editor of Punk who interviewed Reed for the visionary fanzine’s first issue in 1976, described the album’s monumental impact this way: “Metal Machine Music is one of the greatest records of all time. It kicked off the whole punk movement. I mean, it nearly destroyed Lou’s entire career. How much more punk can you get than that?”

So, Metal Machine Music: a grand punk statement, an electronic composition of indecipherable depth or both? Whatever the case, it was one of the most controversial pop-music products of the 20th century. But when looking at the album as art, you’re also inclined to contemplate the artist. Prior to the release of MMM, Reed had gone through a divorce, was in a state of near exhaustion, was cohabiting with a drag queen and had been hit in the face with a brick while performing in Europe. Reed also created the album during a period in his life when he was heavy into doing drugs, especially shooting speed. With references to amphetamines, pharmaceutical handbooks and apocryphal comments like “those for whom the needle is no more than a toothbrush” littering his bitterly rambling album notes, Reed flagrantly trashed the boundaries of both professional and personal decorum.

Rumored, and then denied, to have been a candidate for release on RCA’s classical-music imprint Red Seal, Metal Machine Music was immediately and forever stuck between rock music and a hard place. There were even faint apologies made by the artist for not having a proper disclaimer on the cover, which were angrily rescinded the next time he spoke to the press. With Reed’s uncompromising electronic maelstrom spread across four sides of vinyl and each untitled side listed as exactly 16:01 in length (this, too, proved to be untrue), Metal Machine Music was unlike any other record ever released by a “rock” personality.

While the record itself has been long out of print, Metal Machine Music somehow managed to find new life on CD in Germany and the U.K. Like the celebrated eight-track format, a compact disc allows you to hear Reed’s sonic montage from beginning to end, all without making consecutive decisions to forge ahead with sides two, three and four.

When I began this investigation, I encountered one unanticipated snag that brought my research to a virtual standstill: I kept listening to Metal Machine Music. The more I heard it, the more I liked it, and this concerned me greatly. My desire to hear conventional music diminished, and my friends all stopped visiting. I was feeling down about the whole thing until I bumped into Steve Albini at the Empty Bottle club in Chicago. After explaining my obsession with MMM to him, Albini kindly consented to discuss the record.

“When I lived in Montana in 1977, a friend of mine told me about this weird Lou Reed album that everybody hated but he thought was pretty cool,” says Albini. “He played it for me, and I thought it was just totally captivating, really amazing. The thing that we both appreciated about it was that within the noise, there are these little fluttery beautiful tiny melodic bits, which are probably part of the generative systems that were put together to make all the sounds. Those sounds may not have been orchestrated or intentional in any way, but were there and no less interesting.

“People refer to that record as though it were completely chaotic noise. I have a lot of records that are completely chaotic noise, and that is a total misunderstanding of this record. Whatever Lou Reed’s motive for making it, it’s still a really outstanding non-harmonic piece of music. There were clearly choices made about how much density and which sounds in particular would get layered on top of each other. I don’t hear Metal Machine Music as a feedback-and-improv record; I hear it as a pure sound sculpture. I really enjoy listening to it. It’s not that weird. It’s only weird given that it came out in 1975 and was presented as a pop-music record.”

This is exactly what I was looking for. Someone articulate and knowledgeable who thinks Metal Machine Music is cool and fun to listen to. Perhaps Bangs did know what he was talking about when it came to Metal Machine Music. Reed himself said, “In time, it will prove itself.” Reed also said he laughed himself silly after presenting it as a serious piece of music to the honchos at RCA.

I really don’t know what to believe, but I do know a good controversy when I hear one. Play it again, Sam.

MORE MUSINGS ON METAL MACHINE MUSIC

Bill Bentley (industry stalwart)

“That’s what it sounds like when you’re trying to go to sleep and you can’t. I was very close with a guy who was quite partial to Methedrine for a period there—that was his favorite record. I don’t think Lou did it as a joke.”

Glenn Branca

“I think Metal Machine Music is one of the great classics of late-20th century music. Certainly, if Lou Reed had decided to pursue a career as a serious composer, he would probably be one of the best composers in the world today.”

Penn Jillette (Penn & Teller)

“Teller says, ‘______________’”

Kramer (Bongwater, producer)

“In high school, I worked in the record department of a large department store. I had the opportunity to steal anything I wanted. I took everything I possibly could out the back door. I liked just about everything with the exception of Metal Machine Music. I thought it was shit stacked higher than the band he used to be in, the Velvet Underground. Cut to 10 years later: I now understand those awful-sounding records I used to hate, from the Velvets all the way to MMM. Pure white noise, pure cacophony, pure chaos. I understood, I had respect, but I didn’t really like it. Cut to the present: I now own all Velvets’ recordings on both LP and CD. I still have not found a way to start my day with Metal Machine Music. I still listen unconditionally. I do not think of how the recordings were made or how they were released or who signed them—I only wonder why.”

Jon Langford (Mekons, Waco Brothers)

“I thought it was a great bash against the record company, the critics and his fans as well as an exploration into that kind of music. It’s Lou Reed’s easy-listening album and much less whiney than the rest of his work. Probably my favorite.”

Bob Neuwirth

“The reason I respect Lou Reed is because he never writes about anything he doesn’t have intimate knowledge of. So I’m sure Metal Machine Music was exactly what he was hearing in his head at the time or something very close to it or a Lou-ization of what he was hearing and that’s what makes him authentic. I don’t think artists make insincere efforts.”

Jim O’Rourke (Sonic Youth, Gastr Del Sol, producer)

“I first bought it on eight-track at a Walgreens drugstore along with the Jethro Tull album Songs From The Wood. When I listened to it, I thought for sure that the eight-track was playing backward. It was definitely the first noisy album I ever bought. Later on, I checked a vinyl copy out of the library and read the liner notes with his reference to La Monte Young. I even recorded it onto tape and slowed it down to hear what he was doing with feedback. When I listen to it now, I find it to be quite soothing.”

Robert Quine (Lou Reed, Richard Hell, Matthew Sweet, Tom Waits)

“My friend Lester Bangs was a major fan of it. As a gesture, it’s absolutely 100 percent. It’s 150 percent. It’s 200 percent. It’s great as a gesture, a fuck you, giving the middle finger to the record industry, his fans—just don’t ask me to listen to it. If you want real intelligent improvisation, go back and listen to ‘Sister Ray.’ I spent about a half an hour listening to it, and I think that’s more time that he put into it. My humble opinion is that it’s a total shuck, there’s nothing happening there, it’s a bunch of fucking noise. He did nothing; it’s garbage. As a gesture, it’s magnificent. It took a lot of courage to do it.”

Lee Ranaldo (Sonic Youth)

“I love the thing, and it is a crucial record, both conceptually and in the history of ‘70s rock. A major label put this out! Did Lou have that much clout? We used a loop of it as the background bed of a song off Bad Moon Rising (‘Society Is A Hole’). I’ve always wondered exactly how the sounds were created, not that it matters.”

Sylvia Reed (Lou Reed’s ex-wife)

“I first heard it at a party Lester Bangs gave where he drunkenly swore at everyone that it was the greatest album ever created. He drove everyone out of his apartment by putting it on right then and there. I had just met Lou and was head over heels in love with him and so I went and got my own copy. I intended to listen to it straight through. In spite of my affection, I could only make it through the first three sides before giving up. I still respect it as a great piece of concept art.”

Paul Schütze

“I bought MMM as a teenager the week it came out. At the time I was a devoted krautrock and electric-jazz fan and not remotely interested in American rock music. I had never heard a Velvet Underground album. The relentless single-mindedness and clarity of this most minimal piece excited me in the same way that Outside The Dream Syndicate by Tony Conrad & Faust had a few years before. Rock had become more and more about timbre and less about melody and rhythm. MMM is pure sound. Rock reduced to its essence.”

David Thomas (Pere Ubu, Rocket From The Tombs)

“I remember Peter Laughner liked this record a lot, but I was never sure if it was for the noise or the attitude. I listened to one side and didn’t see the point. It would be interesting to return to it all these years later, I suppose. My opinions should always be considered in light of my basic dogma: Music without vocals is utterly pointless.”

Paul Williams (Crawdaddy, author)

“With MMM, Lou definitely made one of these most memorable and effective conceptual-art statements in rock recording since the Beatles and before, um, Laurie Anderson.”

Steve Wynn (Dream Syndicate, Baseball Project)

“I like side three the most.”

And finally …

Lou Reed

“Metal Machine Music. That was my supreme act. If I left a legacy, that would be it. Like, that was my feelings about the whole music industry and everything connected with it. Because I loved that fucking thing. I don’t give a fuck what they say or what they do, I like that.”