Even though the two bands actually sound very little alike, Radiohead has overlapped to no small degree with Talking Heads over the years. Aside from being named for a latter-day Talking Heads song, Radiohead is a group similarly fronted by a self-admittedly socially uncomfortable singer, has had the benefit of true artistic partnership with something of a musical auteur (Nigel Godrich, where the Heads had Brian Eno for multiple albums), whose rhythm section is its secret weapon and has moved beyond its self-conscious, art-school origins to embrace a broader array of musical styles as it evolved. In short: Frontman Thom Yorke has learned to dance and, in the process, has taught the Radiohead elephant how to more fully inhabit its body musical.

That we are having a discussion about a Radiohead live performance at all in 2025 represents a somewhat unexpected turn of events. Since we last saw Radiohead’s five members together in Philadelphia—Aug. 1, 2018, playing a singalong version of “Karma Police” before quietly stalking offstage—the band hasn’t created a single note of new music together, hasn’t played a live gig and hasn’t much been in each other’s company as a full assemblage in seven years.

Their conspicuous apart-ness ginned up plenty of “Radiohead’s dead” speculation among its energetically devoted faithful and, instead, triggered the release of various solo albums from its members (Yorke, guitarist Ed O’Brien, drummer Philip Selway), motion-picture soundtracks (two from Yorke, four from guitar alchemist/multi-instrumentalist Jonny Greenwood), several side projects (Yorke has released three albums as the Smile in partnership with Greenwood, as well as a recent electronic LP with Mark Pritchard) and joining of other people’s bands (Jonny’s bassist brother Colin Greenwood has been involved with Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds for several years, while Selway has supported British indie act Lanterns On The Lake; then there’s Jonny’s “controversial” partnership with Israeli musician Dudu Tassa). Yorke has also been engaged in other projects: art shows of his original works, curating an exhibition at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum with artist and longtime Radiohead collaborator Stanley Donwood, a stage production of Hamlet loosely connected to Radiohead’s 2003 album Hail To The Thief.

In short: The quintet has been busy doing everything but Radiohead for quite some time. So when eagle-eyed fans spotted the group making a low-key filing for a new LLP earlier in the year—historically, a tell-tale sign of stirrings of band activity—the theorizing began anew. Was a new album afoot? Was some kind of tour in the offing? Was this finally the end for what no less an authority than the late David Bowie described as “the best band around,” a pop group whose experimental leanings and avant-garde genre-bending have profoundly altered popular music over the course of its 40-year tenure since its members first met one another back in their Oxford school days?

So, here we are. Gathered as an excited throng in the graffiti-covered environs of one of Europe’s most artistic, and infamous, capitals. And you would be forgiven for wondering if Radiohead “in the round” was prime prog-period Yes from the look of the band’s stage set, packed liked sardines in a tin box with a vintage/analog kit. A seemingly chain-mail-curtained circular stage sitting in the middle of Berlin’s Uber Arena floor, a space whose relative simplicity is belied by high-resolution digital-image boards draped over every side. The better to both shield the band from its fans, briefly, and to beam large close-up images of them on its sides throughout the show.

This deceptively minimalist approach serves two purposes: to give tonight’s sold-out house of 17,000-plus unfettered visibility to every member of the group throughout the course of the 130-minute show, but also to replicate the close quarters of a rehearsal space. For a band that hasn’t played together in eight years, there must be no small comfort in being able to see each member and look for visual cues inasmuch as the group has learned to listen for them over the years.

What this means in practice is that Yorke is free to roam about as he threads his way through the evening’s setlist, which is drawn from every album Radiohead has released since 1995 breakthrough The Bends. (No “Creep” or Pablo Honey deep cuts, alas.) The group met in London earlier this year to rehearse and feel its way forward together; in the course of this spade-work, Yorke put forward a list of 65 songs covering Radioheads’s vast history that the band then frantically worked to relearn. No Oasis-like “same set, different venue” approach for this contrary lot.

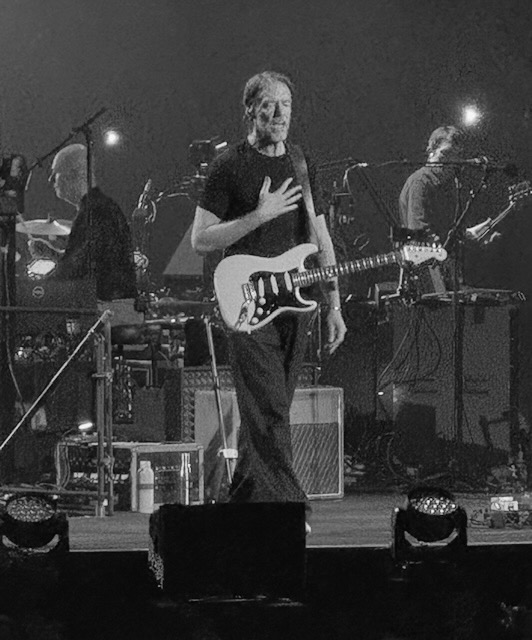

And so the show begins with the familiar interstellar overdrive of The Bends opener “Planet Telex” (played from behind the circular curtain as if it were Pink Floyd’s metaphorical wall) followed by Thief’s “2 + 2 = 5” and frenetic “Sit Down Stand Up,” gathering momentum and confidence. By the time Radiohead makes its way through the morose “Lucky” and “The Gloaming” and then sounds shot-out-of-a-cannon for rhythm-heavy In Rainbows tune “15 Step” and the title track to the band’s era-defining Kid A, it’s clear that Yorke and Jonny’s tenure in the Smile has loosened Radiohead up considerably. There’s a telepathic empathy between the players and some extemporaneous bits and bobs that make their way to the surface of what previously felt chilly, precise and architectural on record. Yorke’s snake-like dancing feels damn near joyous, as if he’s almost having fun re-exploring the contours of the band’s considerable body of work.

What’s noticeable to me is just how much jazz there is in Radiohead’s music now; Yorke is basically spending his evening tunneling through what previously felt like a nearly endless supply of ennui, existential dread and societal AI slop to locate the soul at the heart of In Rainbows tracks such as “Videotape” and “Nude,” both of which take on a gospel-like tinge in this setting that had totally escaped my attention previously. The band has brought along an extra percussionist for this excursion (Chris Vatalaro, who replaces longtime touring member Clive Deamer), which adds a layer of swing to the group’s more reflexive propensity to sting.

This is part of the joy of watching Radiohead rediscover its work years down the line from its initial creation. There’s a triumphant, energetic quality to “Weird Fishes/Arpeggi” and “Idioteque” (the crowd clapping madly along to Yorke’s cardio-warrior dance moves) that probably wasn’t possible when the band was first unveiling these weirdly icy creations on audiences who were likely stunned to find their heroes rejecting their rockist adulation. The set reaches something of an emotional peak as Yorke sits at his Fender Rhodes for Kid A’s “Everything In Its Right Place,” the song’s almost-church-like keys given a kick in the ass via Selway’s drumming, which infuses the track with an almost Stevie Wonder-esque funk edge.

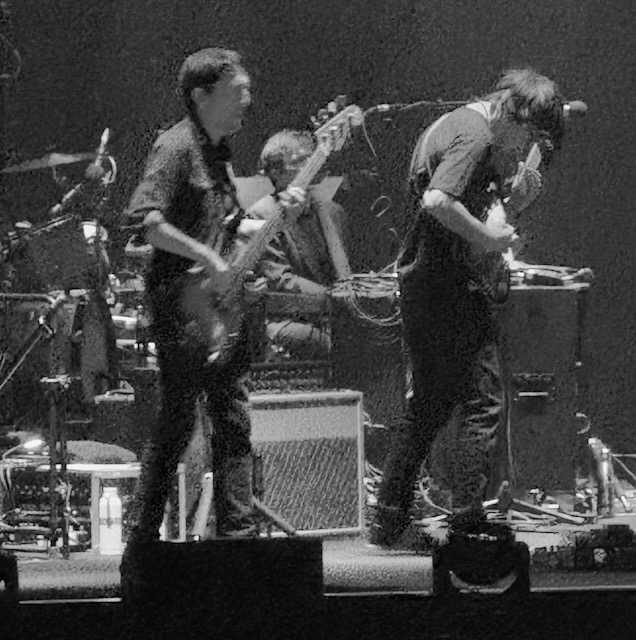

One extraordinary peripheral development is Jonny’s odd-jobs orientation throughout the evening’s set. He’s the muso of the band and a man of multiple duties, working overtime on a variety of guitars, analog keyboards, hand-held effects and even drums, such as the snare stabs he adds to King Of Limbs opener “Bloom,” giving the song a flight-of-stairs-falling-down-a-flight-of-stairs quality.

At this point in the show, the band quickly and efficiently transitions to more EDM-influenced tracks such as “Ful Stop” (whose motorik beat must remind German fans of Krautrock bands Yorke clearly admires, Kraftwerk, Neu! and Can among them). Radiohead could just as easily fall apart at any minute as muster the supreme command of space and silence required to pull off the delicate “Daydreaming” or the polymetered “Let Down,” one of the band’s most beautiful compositions. Jonny plays his twinkling guitar overlay in 5/4 time while the rest of the band adheres to a 4/4 beat, giving it an ever-so-slightly aurally blurry, out-of-focus feel.

That tonight’s concert is attended by as many 18-25 year olds as 50-something contemporaries of the band—and that “Let Down,” thanks to a viral run on TikTok, re-entered the Billboard charts in August, 28 years after it originally appeared on the now-legendary OK Computer—gives a sense of its cross-generational appeal. (The members of Radiohead have children who have reached this age gate, which undoubtedly helps keep the band grounded enough to understand this phenomenon). When Yorke brandishes his red Gibson SG guitar for the frantic “Bodysnatchers,” we begin to recognize the instrument as a tell: He’s ready to rock out.

After a brief intermission, the evening’s encore—starting with the elegiac “Fake Plastic Trees” (which spurs a mass singalong and spontaneous iPhone-generated light show among the crowd), transitioning to the flamenco-adjacent, Thom/Jonny guitar duel of “Jigsaw Falling Into Place” and a funky rendering of “The National Anthem” that comes across as a dance party whereas the recorded version was almost an atonal bleat—brings back the Talking Heads comparisons once again. When the Heads expanded their original quartet in live settings, it turned their chilly, occasionally precious and emotionally disconnected modern-life-is-rubbish observations into celebratory rituals. “National Anthem” is pretty clearly Radiohead’s “Once In A Lifetime,” a release-the-beast moment in the set that finds the band enjoying each other’s company and careening toward the “fuck art, let’s dance” territory its fascination with beats has always implied.

“Paranoid Android” splits the heretofore unseen difference between Pink Floyd’s fear of modern society and Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” (a two-things-can-be-true moment in multiple movements), while Yorke’s turn at the piano for “You And Whose Army?” makes clear that the encore is where his “I may not exactly be rock’s foremost misanthrope, but I play a convincing one on TV” character has been fully unleashed for the crowd’s viewing and listening pleasure. Our joy at hearing old favorites such as the oh-so-’90s “Just” and the gorgeous finale, “No Surprises” (the first time since 2006 the band has closed a set with this epic OK Computer tale of a many-splendored dystopia colored by horrifying banalities and all of those who wish it away through a variety of means, spiritual or chemical as they may be), may completely overwhelm that Yorke appears to be having a laugh at everyone’s expense by proving that jaundiced view of humanity and its suspect instincts go all the way back to the very beginnings of the band. The darkness was always present; it’s just been cloaked in prog and then beat stylings, a coiled, lurking presence literally hidden in plain sight, even during the height of the band’s flirtation with MTV and all the industry’s trappings before thinking better of it more than 25 years ago.

Tonight represented my 10th Radiohead show over the years; I’ve seen the band at clubs, theaters, outdoor festivals, stadiums—literally every venue imaginable for music that has often been far more difficult and inaccessible than a fanbase of the group’s scale would suggest. I feel like I’ve grown up with Radiohead, have experienced its various eras and embrace of/retreat from the mainstream, can relate to the assorted musical cul-de-sacs it’s explored, rejected, then re-evaluated since forming in the late 1980s.

Yorke, O’Brien, Selway and the Greenwoods are generational talents and continue to plow a determinedly unique and independent musical furrow, far above the heads of the majority of their musical peers. And I’ll keep showing up, anywhere in the world they may appear, whenever two or more of them are assembled in this name.

Maybe gravity doesn’t always win.

—Corey duBrowa