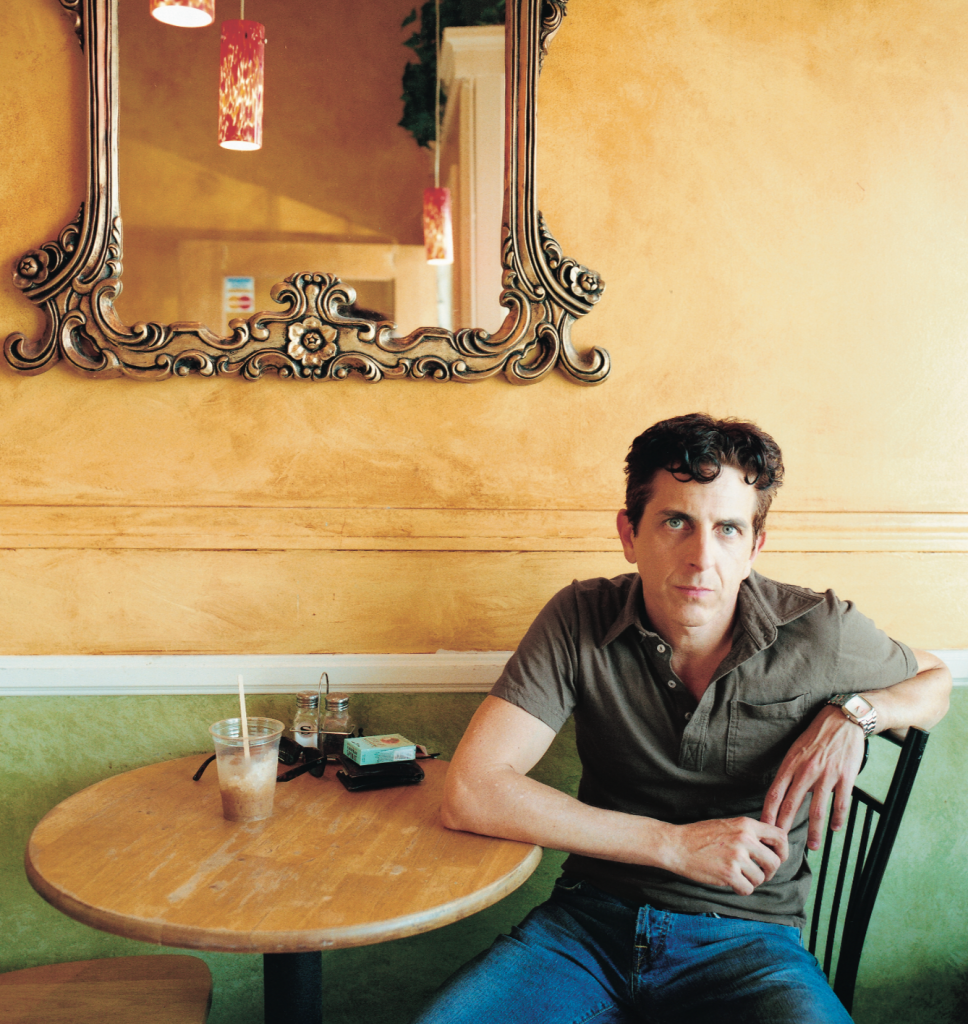

Michael Penn tells the rest of the story

In his dress shirt and rumpled vintage suit, Southern California songwriter Michael Penn emerges from his dimly lit hotel suite like Humphrey Bogart materializing in the Casablanca mist. Come in, he beckons, but be warned: Once you enter Penn’s erudite world—which currently revolves around the year 1947 and all the watershed events that occurred therein—you might as well have arrived on some spooky old movie set. Or maybe you’ve time-traveled back to the year when the transistor was invented, television programs were first beamed across the country, and the post-war generation watched the emergence of the C.I.A., the Nazi-friendly Project Paperclip, the National Security Act and the red-scare witch hunt.

Does all of this history make it into Penn’s latest album, Mr. Hollywood, Jr. 1947?

“Not exactly,” he sighs, sinking into a comfy couch. Delivered with the trademark pneumatic waft of his 1989 hit “No Myth,” these chiming, retro-themed processionals don’t so much re-create the doom and gloom of the past as tiptoe across it.

Sitting in the dark, Penn—47 years old himself—can tell you how conspiracy theories functioned in 1947, in ancient times (he’s an obsessive collector of all things Knights Templar) and in the modern neo-conservative era. During the Cold War, his father, the late director Leo Penn, was a victim of the McCarthy blacklist. His younger brother, actor Sean, has become something of an investigative reporter of late, visiting Iraq, Iran and Hurricane Katrina-crippled New Orleans in an effort to uncover Bush-regime wrongdoings. But Michael would rather focus on ’47.

“I just find it really interesting, because there are so many things now coming to fruition that had their seeds back then,” he says. “I have a fairly Orwellian view of history and the current state we’re in.”

One obvious conspiracy is that corporations are running the music business. Penn issued Mr. Hollywood on Mimeograph, his self-owned, spinART-distributed imprint. Along with his wife, Aimee Mann, he runs a composers’-rights organization called United Musicians. While there used to be roughly 200 different record labels, growls Penn, “now there are only four (major labels). And their m.o., their whole structure, is to basically use music as a delivery system for fashion. They’ve devalued music in the culture so much that I can understand why a kid doesn’t have a real ethical problem with stealing it.”

Even though Mann released her own thematic song cycle in 2005 (The Forgotten Arm, which revolves around the tale of a boxer), the couple’s music remains largely isolated. “We’re both loners when we work,” says Penn. “Aimee has an office in one part of the house, I have an office in another part of the house, and those are our writing rooms. Occasionally, if she has a question about a line or some piece she’s working on, she’ll throw it my way, and I’ll do the same. But that’s very rarely.” He and Mann still test their material at L.A.’s Largo club, where Penn maintains a monthly residency.

The Penns’ greatest familial trait, however, is sheer pitbull aggression. Sure, Sean can drop in on pre-war Iraq and declare the country to be WMD-free. But that’s nothing compared to Michael’s recent quest, which started with the purchase of a flea-market painting for $50. It depicts a young boy, sporting a sash that reads ‘Mr. Hollywood Jr. 1947.’ What a striking coincidence, Penn recalls thinking. All of his recent compositions revolved around that same year. “So I brought the painting home, hung it on the wall above my piano and immediately said, ‘I have my new album cover. My album cover and my album title,’” says Penn. “Hey, you buy a painting at a swap meet, it’s kinda fair game to use it.”

Not so fast. “I just couldn’t feel good about it in this case,” he says. “The artist’s name was legible: Raymond Lark.”

The months-long search began in earnest. Penn initially researched Lark online and discovered he was an African-American artist whose work can sell for between $250,000 and $6 million. “I thought I had a real Antiques Roadshow moment,” sighs Penn, who still hasn’t ascertained the value of the painting.

Penn delayed the release of his album while he pursued the elusive Lark. Emails weren’t answered, phone calls went unreturned. Art critics and college professors couldn’t help him. Desperate for Lark’s cover-art authorization, Penn finally tracked down an Utah gallery where Lark had exhibited during the 2002 Winter Olympics. “I actually talked to a human being there,” says Penn. “This guy tells me, ‘Oh, Raymond Lark died last week.’”

Undaunted, Penn sought Lark’s next of kin via the probate office, coroner and mortuary. But Lark’s estate was in such disarray, a family approval for the use of the painting was out of the question. Penn pieced together a collage work instead.

“I only wish I’d filmed it,” says Penn. “I think it would’ve made a great story, just trying to track this guy down. Who knows? Maybe I’ll write the story myself.”

—Tom Lanham; photo by Pamela Littky