William Parker puts it too plainly to misunderstand, so let’s first give him the floor: “If you haven’t heard the music of Pat Thomas, get hip to it quick.”

It’s not like Thomas is a newcomer. Born in Oxford, England in 1960, he’s been recording for decades, applying his keyboard expertise primarily within the expanded realm of jazz and improvised music. He’s performed with Derek Bailey, Hamid Drake and John Butcher, to name just a few; in England and Europe, Thomas is a reliable presence at jazz clubs and festivals. In the past decade, his profile has elevated beyond that scene, particularly due to his membership in أحمد [Ahmed].

That quartet’s treatments of the music of American bass/oud player Ahmed Abdul-Malik combine ecstatic performances with an astute reassessment of the Islamic undercurrents that have flown through jazz for a century. If you want to spend time pondering what’s wrong in the world, you could note that Thomas did not play a concert in the U.S. until this year. On the other hand, you could just follow Mr. Parker’s nudge and get with what’s right. Hikmah is an easy onramp onto the path to hipness.

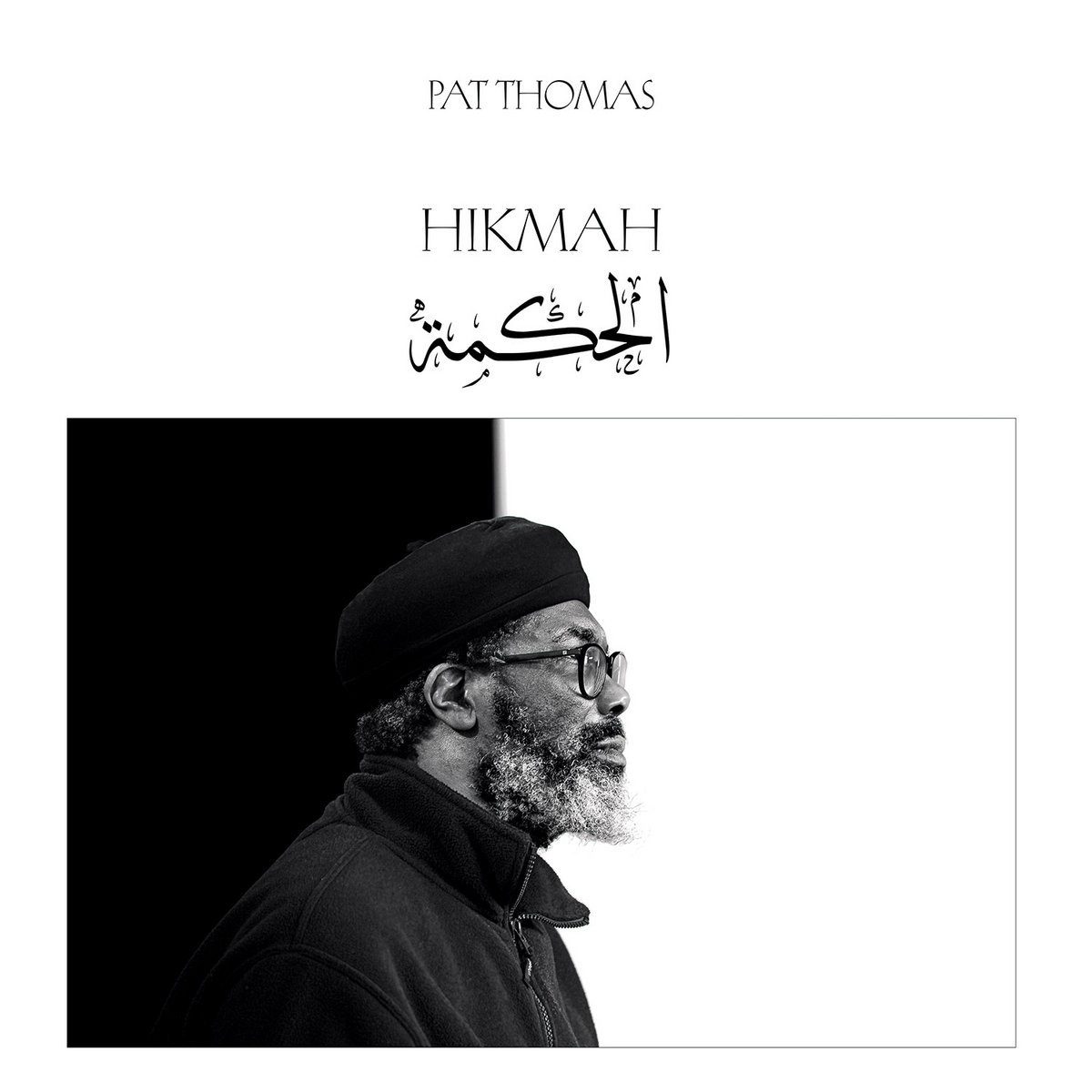

The album, whose name translates from Arabic as “wisdom,” is by no means Thomas’s first solo effort. It’s his sixth unaccompanied piano recording, and if you start counting his digital-only electronic efforts, math might fail you. But Hikmah is his first solo piano album to be released by an American label, and it’s a doozy. Well-recorded and beautifully packaged, it’s a perfect way to get acquainted. Each of its eight tracks is a manageably dimensioned but densely packed articulation of the instrument’s capacity to project a personal vision packed with history and potential when it’s played by the right pair of hands. Among them, you can hear elements of stride piano and Thelonious Monk, inside piano manipulation and rigorously articulated inner logic, pure sound exploration and precise, high-velocity articulation that evidences Thomas’ study of the instrument’s application across idioms.

Most of the pieces are dedications, but they aren’t stylistic homages. Rather, Thomas honors those who have gone deep by going equally deep in his own way. For example, the progression of calorie-rich chords and gently emphatic gestures that comprises “For Toumani Diabaté” has no obvious similarity to Diabaté’s kora playing, but follow the piece and you’ll pick up a vibe of unsentimental reverence and a deep curiosity as to how the music unfolded the way it did. While the combination of resonant low tones, woody reports and sheets of string scrape on “For McCoy Tyner” sounds nothing like the legendary pianist’s music, it likewise takes you on a trip that’ll make you feel like something’s changed, at least for as long as you listen. And who can’t use a bit of transformation these days? [Tao Forms]

—Bill Meyer