Even if he sold the world (or its products) on TV commercials and fell some distance with disappointing jungle/industrial albums of late, remember that Ziggy went down so he (or she) could rise again. With the new Heathen, David Bowie is more the scary monster and less the super creep. By A.D. Amorosi

If post-September 11 New York City is such a go-go, it doesn’t seem so “Jean Genie” giddy at present. Instead, Manhattan seems positively shell-shocked. This shiny, apocalyptic setting is apropos in which to meet David Bowie and deal with Heathen, his finest album in 22 years. Not since Scary Monsters has Bowie’s innate paranoia reflected itself on communal living, embittered politics and embattled daily existence. Heathen is the sound of a 55-year-old man at the very top of his game—as astonishing as Barry Bonds bashing around the bases or Warren Beatty in Bulworth intoning all the right epithets with ribald grace.

“He’s deeper, more focused and happier—but serious,” says Tony Visconti, who’s produced some of Bowie’s best work: 1970’s The Man Who Sold The World, 1975’s Young Americans and Scary Monsters, as well as his so-called Berlin trilogy of 1977-79 albums featuring Brian Eno as collaborator (Low, Lodger and Heroes). After two decades apart, Bowie phoned Visconti out of the blue to come in and work on Heathen.

Upon my arrival at the Soho Grand Hotel, Corrine “Coco” Schwab (Bowie’s longtime personal assistant) seems interested in how long I’ve been aware of Bowie in a real way. Was I a kid? Was I someone who only knew Bowie from Let’s Dance? No, I was a Bowie Kid who grew into an objective, sometimes pissed-off critic. I stayed a fan through it all, with several odd haircuts, a nagging Gitanes habit and brief Bowie interviews strewn across years to prove it. I stayed interested, though sometimes disappointed and appalled at the results of his work. And now it was time to turn and face the strange.

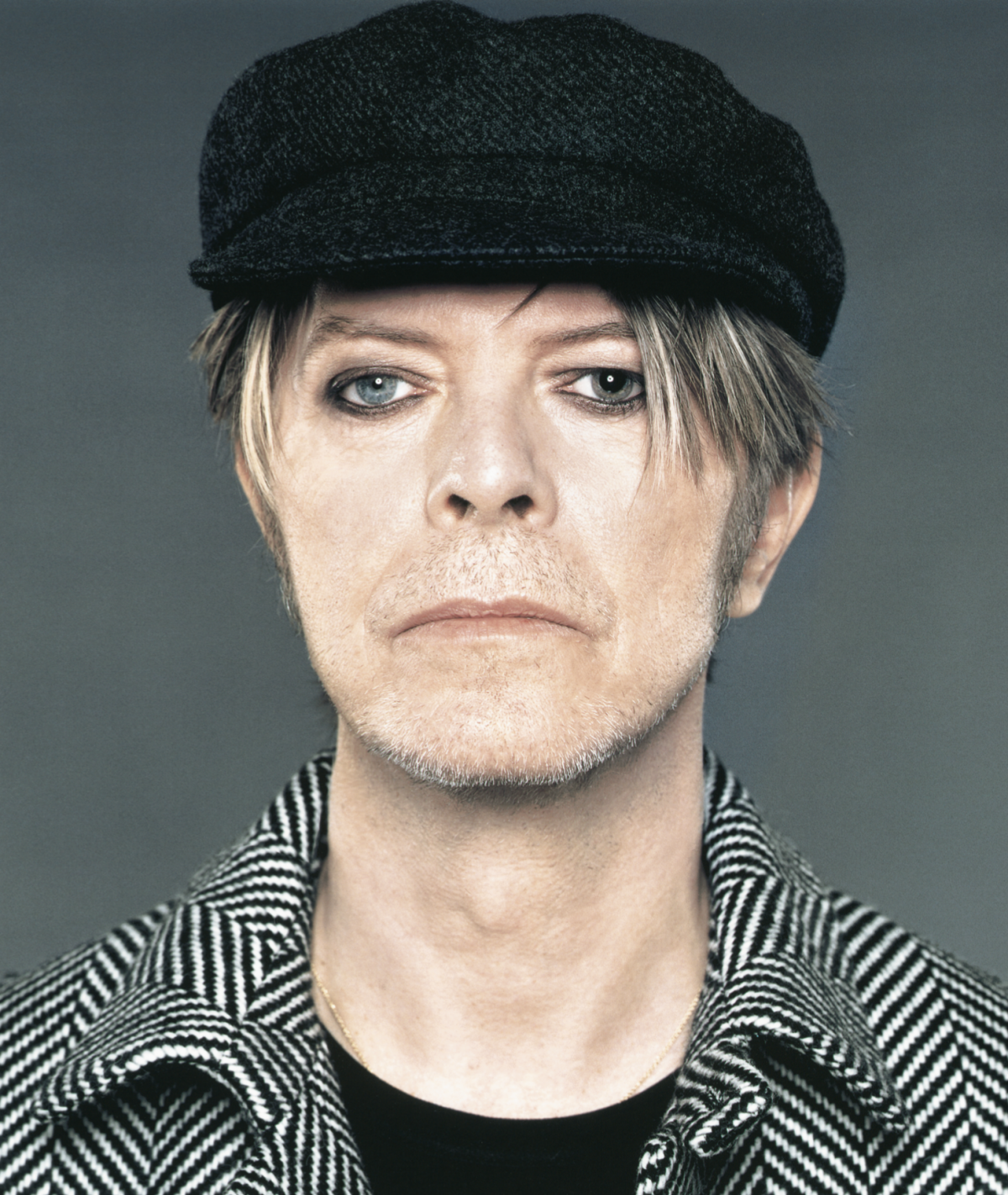

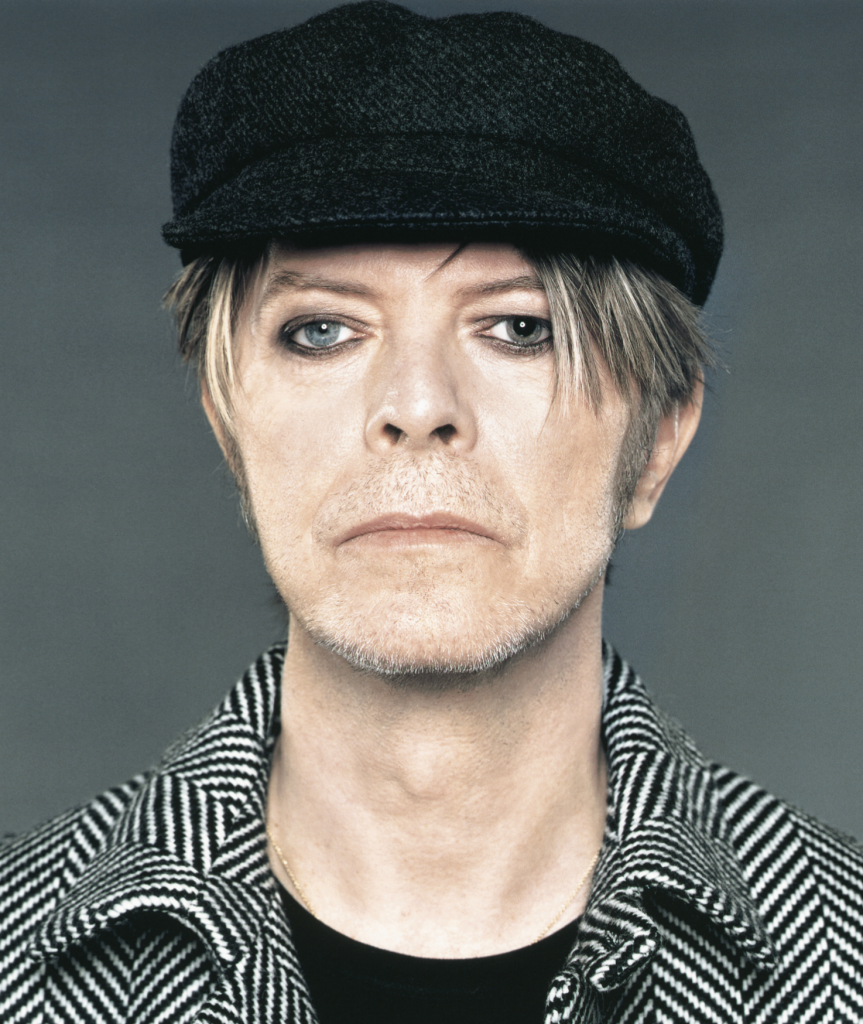

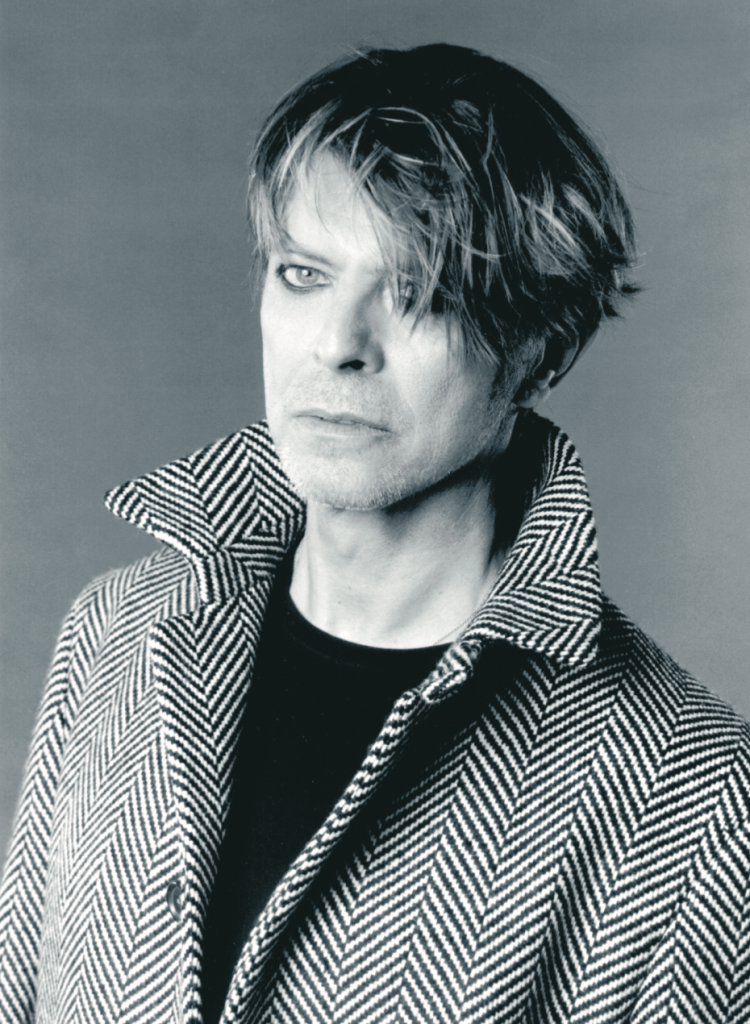

“You must’ve been a child, my god,” Bowie says after hearing bits of my chat with Schwab. Dressed in a brown corduroy shirt and khakis, Bowie is very up and about. After offering each other Listerine strips, he raves about the addictive properties of the wafer-thin blue blast. “When will I feel the effects?” he laughs, remarking on the drug-like quality of its packaging.

Bowie is mentally calm and physically restless. He sips his coffee. Runs his fingers through his scruffy blonded-brownish hair. Covers his face with his hands and rubs his eyes a lot. Pulls at his socks, which sag down to his boat sneakers.

•••

MAGNET: The last time I spoke to you (in 1997), you were painting Minotaurs. Great big ones.

Bowie: I’ve gotten away from the visual arts since last we may have met. It seems I’ve transferred that energy—my Minotaur needs, so to speak—into what’s become Heathen. Still, that which is Heathen is almost a continuum.

Truth, romance and fear, which have driven a lot of your work, are the keys to Heathen. “Sunday” and “Heathen” bookend the record with the same frightened vibe, much like Scary Monsters. Where are you in terms of your own psyche now?

These feelings or lyrics come from a very individual source. I think this is one of my more intimate albums. It’s not written from some diffident, objective stand. I mean, I was really subjective about it all. I wanted to deal with a lot of big things in a small way and didn’t want to get too grand about any of it. Rock postulations about world overviews are usually very embarrassing. I can’t do them. It’s not something I’m good at. [Laughs] I’m good at low-level anxiety and nagging fear. Things we can’t quite put our fingers on, but when you hear them from my mouth, you know what I mean. I nail that edginess that keeps us up at night. I understand it very well. And though maybe I can’t articulate it, I can manifest it into musical form.

If you can make big issues small, when do the great questions start getting littler?

Both “Heathen” and “Sunday” are templated by Four Last Songs by Richard Strauss. He was 82 when he wrote them, and they’re so moving. Those were in the back of my mind: how to address big questions when you’re, hopefully, not at the end of one’s life but rather when you’re approaching an area where the bigger questions are fewer and fewer. Before I’m very much older, I assume, there should only be one or two big questions left of any importance.

Do you think these bigger themes made you want to seek comfort in someone like Tony Visconti, with whom you’ve made your most disquieting records?

We’ve actually stayed really good friends over the last few years. When we first started talking about working together again, I said I would be immediately committed, but only if I had the right weight of songs, material with real gravitas. I knew there’d be obstacles if we were to try to return to what we’d done before. He agreed wholeheartedly. It wasn’t about recreating the old times. I value the stuff we have done too much to cheapen it.

On tracks like “A Better Future” and “Sunday,” you make amazing claims of a god—almost extorting to the point of Nietszchean equality.

I think something like “A Better Future” comes about while looking at my child. Or your child. Those demands come immediately to mind in the incredibly anxious times we’re living in. I can’t think of a time quite so troubling. The only time I can remember where the air was so fraught with danger was the missile crisis during the Kennedy period. Overwhelmingly scary. Remembering that as a kid, it struck me in that even my parents wondered whether everyone would get out of this alive. It’s a bad climate now. But it was almost as bad when I was writing this stuff at the beginning of last year.

There were certainly large signs—imminent dissatisfaction—indicating some doomsday scenario.

Exactly. It’s not something that’s suddenly come upon us. It’s manifested itself in so many ways for so very long. That low-level anxiety has been with us forever. I remember writing about such on “Loving The Alien” in 1984. Actually, there was a British attaché connected to the Middle East who I read had said, “If I have to hear any more of this Palestinian hatred of the Israelis, I will go mad.” This same attaché several days later told the press, “I’ve just been lectured on two full hours on Zionism in the citadel. It was enough to make me want to go Islam.” That was 1937. Unbelievable, right? That’s why I write with such demand. I mean, what is the gag, God? What is our breaking point? The teasing is too much.

•••

“Even his joy seems serious,” says Visconti of Bowie. “There’s a spiritual theme that runs through his work and essays his personal relationship to God—or whomever he believes a god to be—that’s quite singular. Years ago, he was very easily swayed to drop something, very easily distracted. This time, he never came down from the mountain.”

Visconti and Bowie worked on Heathen last year at Allaire Studios in rural Shokan, N.Y., a quarter-mile above sea level. “Recording Heathen was like being on Mount Olympus,” reflects Visconti. “David took very few phone calls in the months we worked on it. For four months, we lived together completely, just like we did during Heroes or Low. Our conversations, whether reading stories to each other from the newspaper or discussing sonic equations, flowed from dining room to studio.”

Unlike Bowie’s coke-fueled past (look at your Creem magazines between 1974 and 1976, kids), there were no crutches holding up Heathen. “I don’t like or want any cookie-cutter scenarios or artists in my production life—nor do I want to hear about slick record-company bullshit,” says Visconti, who also produced hits for Marc Bolan’s T.Rex (his first big discovery). In the annals of glam rock, the Bowie/Bolan rivalry is legendary: It caused Visconti to temporarily split from Bowie prior to 1972’s The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, glam’s defining album.

With its intimate mix of glitchcore noise and subtle electronics, Heathen is decidedly un-slick. It’s unhampered by the jungle and industrial sounds that earmarked 1995’s Outside and 1997’s Earthling, respectively; it lacks the overproduced quality of Bowie’s ‘80s output. Here, he’s fearful and pissed off, confused and cocksure. “The songs (on Heathen) weren’t personal—they’re observations,” says Visconti. “But they felt relevant to me, relevant to their times. Like all his best albums do.”

MAGNET: You started writing this stuff in February of last year—songs and melodies that had a sense of direction. All on your own. Without laying blame or pointing a finger …

Bowie: Ah, but you will.

Was losing (longtime guitarist) Reeves Gabrels as a collaborator important for you in creating this renewed weight within your songs?

Not at all. I believe he had an awful lot of problems he presumably wanted to deal with, along with reasons of his own as to why he did not wish to be in New York. I can’t say more than that. I did adore writing with him, but you know, I’m a really good writer. I don’t need to write with anyone else … The last thing I need is someone to write with. Practitioners at interesting sound—that I need. That’s what Reeves is best at: implicating guitar into most unique places in unique ways much the same way as his idol, David Torn, who plays a great deal on Heathen. I think Reeves peaked at Earthling.

Heathen is a more subtle work. Maybe Torn was best for this material.

Best man for the best job, yes. I always know going in what I want from a project—what I want it to be or sound like. I’m very accurate about what the weight, sound and scope should be. I choose my musicians per project. That’s been problematic for me always. Musicians get upset by the fact that, even if they’re touring with me regularly, they might not be on a given record. I’m like an architect. If you’re building a structure with a lot of aluminum, you don’t go to a bronzemaker for the fitting. I don’t go to a bronzecaster when I need a bricklayer. The sound I was after was an ethereal quality. When I figured that out, I got who I needed. I don’t want to bully six people into sounding like six other people.

Musicians more than likely find you to be disloyal or unfaithful—the cold Bowie so often referred to.

It may just be that I’m not close enough to being a rock ‘n’ roll animal. It doesn’t mean if we’re working together that I’m your bosom buddy or that we’ve cemented an ongoing relationship. [Laughs]

So much for our dinner date. There’s a restorative quality to Heathen, a homemade feel. The closest thing I can compare it to is reading about Jackson Pollock at work in the Hamptons.

Oh, absolutely there is that. And there’s my playing. Diamond Dogs comes close—only sonically—because there’s a lot of my playing on that. And Low, too. A lot of the keyboard (on Heathen) is me: the chamberlain and mellotron stuff. There’s a large piece of me—as limited as my musical talents that appear on this album may be—that just has that naive, crusty, homemade quality. Pete Townshend said that upon coming in and hearing what we’d done that he thought it had a cheap, raw, homemade mystical quality like Ed Wood meets Franz Kafka. And I thought, “Yeah?” Then I thought, “Yeah.”

As unfinished as Heathen sounds in the end, there’s still an epic melodicism that hasn’t been part of your sound since—I can’t say when, really.

Maybe that’s because I applied myself to the writing process. I wanted structure, because these were songs about things. More narrative. Martin Amis’ recent collection of short stories talked about Anthony Burgess, who in one of his books put forth the notion that there are A novelists and B novelists: A is drawn to character, narrative and action; B is more interested in the juxtaposition of ideas, wordplay and theory with narrative as secondary, something to throw the idea across. That how I deal with my albums: as As or Bs. Sometimes, I know I’m going in because of ideas, and the songs are secondary—something to throw ideas over. Low is B. Outside is B, mostly; there’s a lot of A in that, too. I mean, what have we brought ourselves to in art in order to deal with corpses and Minotaurs and paganism? But Heathen was about songs. It’s a very A thing. Anything else was to shore up the weight and musculature of the song itself.

I’ve read what you wrote for Mick Rock’s photo book Moonage Daydream, which is a lot of words: 15,000. I’ve read the stuff you’ve written on Jeff Koons, too. You’re quite an essayist in that you maintain an intellectual standpoint, even when there’s the appreciation of a fan in you.

Thanks. I’m really inadequate. Trite, even. I feel dwarfed by the likes of Ian McEwan. His work is so circular and so resolved. So many writers walk away from their own endings. They don’t know how to conclude or to bring a thing to a satisfying ending. Even a strange, modern-ended conclusion should satisfy that need for finality.

Moby (Bowie’s touring partner for this summer’s Area2 festival), Dave Grohl (who plays guitar on Heathen) and Air (which remixed Heathen’s “A Better Future”): What do you mean to them after so much time? Don’t you think, to a certain extent with Moby and Air, there’s so much the Bowie copyist in their work?

Well, Moby’s a true mate of mine. He did the finest remix of one of my songs, “Dead Man Walking.” Friends ever since. And now he lives literally two streets down from me. [Laughs] Air—well, they’re so influenced by what I’ve done in the past …

That they owe you money?

Ha, yeah. You know what? They’re the first people to acknowledge such. [Laughs] Unlike some of my contemporaries, though, I wouldn’t have put them on my album. [Suddenly serious] I was very careful that the album was intrinsically what I needed to do for me without distraction. Too many people work this thing where they get all these other artists to litter their records. They’re doing themselves a disservice. For me, it wound up as just Townshend and Grohl. Townshend, you must remember, is a very old friend and certainly not one guy you’d consider a trendy name. Besides, he practically e-mailed his solo to me. And Grohl—it’s just one song. He was right for just that one song.

At age 55, what’s your opinion of your own relevance?

I’m more worried about the relevancy of popular music, period. I’m deeply worried about the disillusion of it. I’m not sure it’s a currency that matters much anymore. I hate having to say that because I’m in it. I’ve devoted my life to it. I’ve written it before, and I will write it to the very end. But it’s kind of like Gutenberg’s Bible. Now that printing is so available, it doesn’t really have the weight it did when only the priests owned the words.

I couldn’t agree more. Blame MTV. Blame the internet. Blame the E! Network. Too much available info. Nothing secret. Nothing sacred.

Back then, there—it, pop—was hope. It was manna from heaven. It was something very special indeed. Pop music—my music—especially in the age of the Internet, has and will continue to hold a different place than it used to. And that, sadly, equals only a choice accommodation for one’s lifestyle. It’s no longer the word from above or the battle cry for revolution. I don’t think it will ever do that again. Maybe, of course, black music can still do that. But rap and hip hop seems so in a rush to commodify itself, to create its own economy, that it may miss the boat.

But whether you’re selling to kids or to adults …

Yeah, yeah, yeah. [Disgusted] I don’t. I don’t have to sell to them.

•••

At age 10, I made the acquaintance of the first and most famous of Bowie’s self-made characters, the one with the orange hairdo. Ziggy Stardust rolled into town in 1972 and immediately became an icon of sexuality, fashion and music. Ziggy—an electric-guitar-surfing androgyne with a death fixation and really dodgy jumpsuits— would become (despite being influenced by Lou Reed and Iggy Pop) the inspiration for all alien sex boys and girls (including Reed and Pop, whose records Bowie produced) that followed: punk, new wave, fashion, film, gay/bi-centricity and beyond. The beyond—and you have to try to think back that far—meant you could be whatever you imagined: for a minute, for a year. Anything and everything was permissible. Liberation. Lifestyle. Life. Style. This waify, mascara-wearing Brit created genuine social change. And face it: Neither the pen of Dylan nor the swagger of Jagger really ever did that. Bowie may believe his work was always more personal than political, but he turned people around in ways that mere words or pouty lips never could.

Bowie isn’t celebrating the 30th anniversary of Ziggy Stardust as he had originally planned (with a boxed set and live performances; there is, however, a remastered edition of the album, with a second CD of familiar outtakes and rarities). Maybe it’s because he left his contract with Virgin Records in a huff late last year. Maybe it’s because Velvet Goldmine did it badly and Hedwig & The Angry Inch did it better. Maybe it’s because Bowie killed Ziggy off on film (in D.A. Pennebaker’s 1973 documentary Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars), and that’s that.

•••

MAGNET: What do you make of Ziggy Stardust and the fact that 30 years on, people still often weigh your work—as well as their own lives or aesthetic— according to it?

Bowie: [Almost dismissively] I have incredibly fond feelings for that project and that particular time. [Pause] Maybe I just can’t get excited about it right now—despite it being 30 years—because it’s only time that somehow makes it bigger in people’s minds. Maybe

You’re the only one not celebrating. Ziggy meant something to people in the early ‘70s disillusioned with the colorlessness of rock and the blandness of youth.

It is incredible that Ziggy’s even remembered at all—and with such love from a lot of people. It certainly helped put forward the idea of being able to create your own way of dealing with the world or your own world, period. That you didn’t have to fall within the confines of what was laid out for you. If you wanted to—outside of the usual forum of politics—you could be quite radical in the way you approached your own life, your sexuality, mode of dress. The idea of self-invention or reinvention, whatever, hadn’t ever really been postulated by anybody before. It wasn’t something on the table at all. In that way, he was very important.

How would you explain Heathen to fans of the Bowie continuum? Of Ziggy? Or people who began to dig you with Young Americans? Who jumped onto the Bowie at Let’s Dance or Low?

That’s funny, because that’s the full circle of you. You know me. You’ve grown with me for 30 years. So you know that I obviously wouldn’t ever try to explain. It’s the same adage I’ve used before, and it still sounds as pompous: I have to write for myself. I have to write something that I can then record and put on and listen to and say, “That’s the best that I can possibly do at this particular time of my life.” Then I put it out. It has to be that. I can’t address other people’s concerns or figure why I write.

So it’s important for you to maintain a secret life to the record.

I think the isolation of how and where we recorded gives Heathen that secret inner life. And light. It was about getting up in Woodstock-area light—it’s very high—on top of a mountain, 6 a.m., before anyone else got down to the studio and writing that way. It’s Pollock land. The height was a perfect counterpart to the feel of the lyrics.

But surely you know Heathen isn’t a daily journal or diary that no one reads. And that even the best intentions …

Well, I do want to communicate. I do try. I don’t want to be the guy that no one is meant to understand what he does. I think several of my albums really communicate their ideas very well. And that for me is a successful opportunity. I think that Heathen is one of the more successful at doing that particular job. And it’s also a delightful sound. Its sound. It sounds … musical. [Repeats that under his breath]