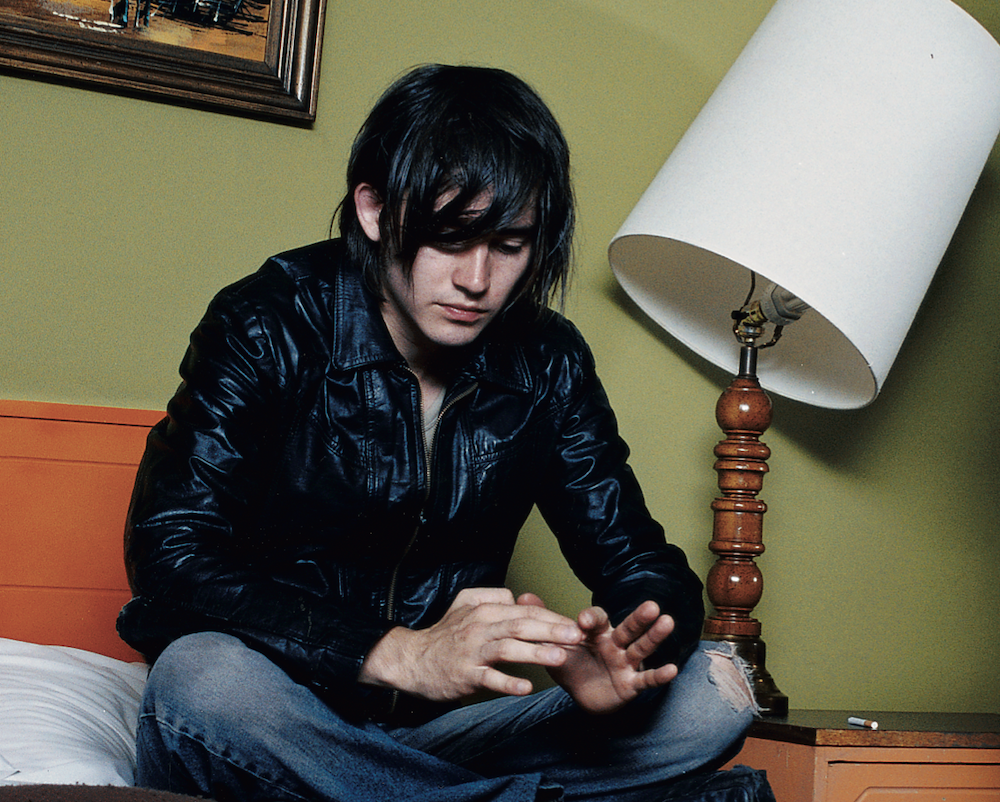

Do not disturb: MAGNET glimpses the inner circle of Black Rebel Motorcycle Club as the band of outsiders takes on the world, one city at a time. By Bob Mehr. Photos by Christian Lantry.

Rotting whale carcass has a foul, distinctive odor.

Even small bits of decaying cartilage and tissue can emit a stench uglier than the strongest human stomach can bear.

So when the gnawed, damaged corpse of a 40-foot, 20,000-pound whale washed up on the shore of San Francisco’s Ocean Beach in July, the smell was overwhelming. Even so, scores of people some wearing surgical masks, others holding rags to their faces came to see the beast. They marveled at the near-biblical proportions of this once-proud behemoth. Many said a prayer.

Eco-friendly California quickly adopted the whale as a family member. It was given a name Obee and mourned by throngs of heartsick onlookers. For three days, camera crews and news reporters descended on that stretch of surf, grimly wringing their hands and offering requiem. Obee, it was announced, would be buried in the sand during a formal ceremony on the morning of July 22.

But the night before the whale could be given its last rites, someone came to Ocean Beach armed with a jagged knife and carved a series of letters across the width of its body. When dawn broke and the horrified masses glimpsed the mutilation, they were shocked.

Who would do such a thing? How could they desecrate one of god’s creatures? And what, they wondered angrily, does “B.R.M.C.” stand for?

When Black Rebel Motorcycle Club bassist Robert Turner hears this story a day later—in the middle of soundcheck at a club not far from the scene of the crime—he stops and grabs the sides of his head, as if to steady himself. “I think,” he says, only half-jokingly, “that I need to go lie down.“

It’s an undeniably bizarre climax to four extraordinary days spent with B.R.M.C.—an endless blur of press, performance and promotion. By the time the band reaches San Francisco—under increasingly surreal circumstances—it feels like we’ve gone all the way through the looking glass. But perhaps, as Lewis Carroll wrote in his Alice adventures, we should begin at the beginning.

Portland, July 21, 7:27 p.m.

Airport security has a hard-on for Robert Turner.

Maybe it’s his lanky frame, coiled mop of hair or matte-black uniform. Whatever the reason, something about Turner screams “random bag check.“ It’s gotten so bad that Turner has taken to hiding his hair under a white Titleist golf hat. He insists this ruse is generally foolproof, but today he forgot his headpiece at home, and the staff at LAX gives him a full shakedown.

Consequently, Black Rebel Motorcycle Club misses its flight to Oregon, and the last rays of evening sunshine are filtering through the windows of Portland venue Berbati’s Pan when the band finally arrives.

This is B.R.M.C.’s first American tour in more than a year. It’ll likely be its last playing small clubs. The band’s sophomore album, Take Them On, On Your Own (Virgin), will be out in a month, and there are a few more West Coast dates before heading back to Europe, where it will storm the main stage at Leeds and headline Reading with Blur, Metallica and System Of A Down.

B.R.M.C.’s six-man crew is hurriedly setting up for the night’s show. This includes Turner’s father, Michael Been, currently hunched over the soundboard with a flashlight between his teeth, trying to dial in tones, as guitarist Peter Hayes flits about the stage restlessly. The airport delay has screwed up an already tight schedule. Doors open in 15 minutes, which means the band will have to barrel through soundcheck commando style. Turner sheds his green army coat, grabs his bass and turns only to find drummer Nick Jago AWOL.

“Where’s Nick?“ he shouts.

B.R.M.C.’s road manager announces the drummer has chosen this particularly critical moment to go out and get a massage. Even the usually stone-faced Been has to laugh. A fearsome talent with a wild-eyed, barely hinged manner, Jago is also a certified flake.

The first time the members of B.R.M.C. played together was 1998. Jago showed up at San Francisco’s Cocodrie club to see Hayes and Turner perform with an art-noise outfit called the Wave (fronted by current Stratford 4 singer Chris Streng). “Let’s say Nick had more than one drink that night, and he ended up coming onstage and shaking the maracas,“ recalls Turner.

“At the end of the song, he smashes a maraca into the cymbal and it explodes, spilling this massive cloud of white powder everywhere. Then he just kinda straggled off. It was a weird moment.“

Things would get weirder still that night. Amid a blizzard of illicit substances, the partying ended with Jago trying to jump out of Hayes’ van as they sped across the Bay Bridge. “We were ready to kill him before that, anyway,“ says Turner. “He’d said enough things and done enough things that were out of line. I just remember sitting in the van seeing Pete holding on to the back of his pants, trying to keep him from jumping out with one hand while trying to drive with the other. After that, we swore we’d never speak to Nick again.“

A month later, they asked Jago to join their new band.

Nick Jago: Monkey Man

Back in Portland, Jago finally appears and B.R.M.C. bangs through soundcheck. As the crowd filters in, the band cools off upstairs in the club’s fan-filled green room. Jago is walking around chomping on a banana, reminiscing about bad early-’80s television.

“D’you remember Manimal?“ he asks in his drowsy

British accent. “Where the guy morphs into all these different creatures? I used to love that show. Got me thinking, if we were animals, I’d be a monkey, Peter would be a wolf, and I think Robert would be … a bat.“ At this, Jago laughs hard, arching a set of thick, dark eyebrows that hint at his exotic heritage. Born in Iran to a Peruvian mother and English father, Jago lived in Argentina, Venezuela and Peru before settling in Devon, a sleepy seaside county in the U.K. (It’s this somewhat convoluted immigration history that’s caused Jago’s much-publicized visa problems. “The whole thing looked really bad to the FBI,“ he says.)

Jago grew up in a musical family his mother and brother played guitar but he never pursued an instrument himself, enrolling instead at Winchester School of Art with the intention of becoming a painter. By 1996, Jago’s parents were getting divorced, with his mother and siblings leaving England for California. Increasingly unsatisfied at Winchester and prone to fits of rule-breaking behavior, he was eventually kicked out.

“I always say I left art school ’cause I decided I wanted to play music,“ he says. “But the real reason that I left was that I went nuts. I think it was a bipolar episode. A manic-depressive episode. It only happened once, but it was really, really intense. There were absolutely no drugs involved. I had six weeks straight of feeling high as a kite. And then a six-week period of feeling really low. I guess I just came to a point in my life where I felt like if I wanted to make things happen, I just needed to go out and do it.“

Jago left England and settled in the Bay Area. The next two years were a fairly bleak existence. “I couldn’t find a niche anywhere,“ he says. “I was really fucking depressed, just working odd jobs. Dead-end jobs in San Francisco.“

He eventually discovered a clique of music-obsessed misfits drawn to the Mod Lang record store in Berkeley and the weekly Popscene night at 330 Ritch Street. His passion for Britpop and the Creation Records catalog began to flower, and he inherited his first drum kit (a beat-up Vistalite set he still uses) from a neighbor.

Among the few people who answered the “musicians wanted” ad Jago placed in a local paper was a withdrawn bass player named Robert Turner. Nothing came of the afternoon they spent playing together, but the two subsequently began taking notice of one another in clubs and record stores around town. Soon after meeting Turner, Jago heard talk of a strange, six-string wunderkind while hanging out in an East Bay coffeehouse. “They said, ‘There’s this weird kid, but he plays really good guitar, and he works at this gas station,’” says Jago. “One night, we were going into San Francisco to party, and I ran into this guy at the gas station. We just exchanged glances.”

Months later, at the Wave’s show at the Cocodrie, Jago was shocked to find Turner onstage playing with the same sullen gas-station attendant, Peter Hayes. Despite the fireworks upon their initial meeting, Turner and Hayes invited Jago over on Halloween night in 1998. The trio—which christened itself the Elements—ended up jamming for seven hours straight in Turner’s living room. “It clicked,” says Jago with mild understatement. “We definitely clicked.”

Portland, July 21, 10:23 p.m.

The 500-plus packed into the club surge close when the lights go down. As Turner knocks back a Red Bull and hurls the can into a corner, a shaky Hayes continues chain smoking. Jago whispers something in their ears as B.R.M.C. strides down a flight of stairs to the stage.

They come out fists flailing with a fine-honed version of “Spread Your Love.” After that, it’s onto the shock imagery of “Six Barrel Shotgun.” They say little between songs, play most of the new record and encore with a ferocious version of “Whatever Happened To My Rock ‘N’ Roll (Punk Song)” that nearly strips the paint off the walls.

After the show, Turner and Jago head off with their girlfriends. Hayes—currently in the midst of some romantic turmoil—is left to find a drink alone. A sour-faced barmaid tells him it’s past last call, so he sulks off to the band’s bus to grab a beer. Hayes is drinking in the alley behind the club when a police car screeches to a halt in front of him. A cop emerges in attack mode brandishing a shotgun. He’s soon joined by a second officer, also locked and loaded. Frozen for a moment, Hayes soon realizes they’re not after him but what turns out to be some madman waving a gun down the street.

Wary of being caught in the crossfire, Hayes retires to the bus. Improbably, this marks the second time in two days B.R.M.C. has found itself in the middle of a potential shootout. Twenty-four hours earlier, stuck in traffic in L.A., the band witnessed a pistol-pulling road-rage incident.

“We’re always in the thick of things,” mutters Hayes bleakly, crushing out a cigarette. “I think we attract it.”

Seattle, July 22, 1:33 p.m.

“I don’t know why we’re here,” mumbles Robert Turner as a Virgin Records employee shepherds B.R.M.C. through the sterile two-story headquarters of DMX, a satellite-music service for retail outlets like Abercrombie & Fitch and Pottery Barn. “We always end up doing more damage than good.”

Turner and Jago leave their record-company handler outside and enter a cramped office with a DMX cameraman and producer. There’s tension in the air, and small talk is strained. Turner and Jago keep their sunglasses on. What the band thought was going to be an interview turns out to be a session cutting station identifications for DMX’s various in-store networks.

“Um, we’re Black Rebel Motorcycle Club and … you’re watching, uh, Skechers TV.”

Their delivery grows increasingly pained, as Turner and Jago become aware they’ve been duped into the setup.

“Hi … we’re B.R.M.C. and … you’re watching, um … Spin … TV.”

They manage to get through about five spots before a visibly uncomfortable Jago stops.

“What’s all this for again?”

The producer tries to explain something about multi-formats, cross-promotion and how a ton of 15- to 24-year-old girls are gonna see them. None of it registers with Jago, who stares back blankly.

“C’mon, Nick, you know someday you’re gonna want to impress a 15- to 24-year-old girl,” jokes the slightly more cooperative Turner.

“It just feels like we’re doing advertisements,” says Jago tersely.

The DMX staffers—accustomed to having visiting musicians cheerfully jump through such promotional hoops—are stunned. B.R.M.C. relents, agreeing to go through with the originally promised Q&A session, but it’s a strained five minutes of boilerplate chatter. The cameraman tries to lighten the mood by suggesting they answer a series of “fun” questions put together by DMX’s marketing department. “They’re not gonna want to answer any of these,” says the dejected producer. He takes a deep breath and reads one aloud: “OK, if people were blue jeans, you would be … ”

Turner and Jago brush past the nervous Virgin rep, who tries to keep up as they practically sprint out the front door.

L.A. Story

Encouraged by the success of the Brian Jonestown Massacre—another S.F. combo that relocated to Los Angeles—the Elements migrated south in 1999. The response in L.A. was swift and dramatic: Within months, the band—now calling itself Black Rebel Motorcycle Club—and its self-recorded, self-produced 13-track demo became the hottest thing in Hollywood.

Initially leaning toward an indie deal, the band was soon fending off multi-nationals and celebrity CEOs, dining at Rick Rubin’s mansion and fielding offers from Noel Gallagher’s label, Big Brother Records. The more they resisted, it seemed, the harder people came after them. Unlike most bands eager for promises of stardom, hefty advances or extravagant budgets, B.R.M.C.’s single sticking point was simple: complete creative control—from recording to album covers to videos. In the end, the band took less money in exchange for such guarantees, signing with Virgin.

“If I had any reservations early on about signing them, it simply had to do with the fact that they were not temperamentally well-suited to be on a major label,” says former Virgin A&R head Tony Berg, now president of the ARTISTdirect label. “It had to do with their sensibility and their privacy. ‘Distrust’ is too strong a word, but they created a cocoon for themselves that’s nearly impenetrable.”

Berg knows whereof he speaks when it comes to “difficult” artists. He began his career apprenticing with legendary wildman composer Jack Nitzsche before going on to work with a collection of iconoclastic talents from Aimee Mann and John Lydon to the Replacements (“very similar to B.R.M.C.,” says Berg of the latter).

The making of B.R.M.C.’s self-titled debut turned into a torturous affair. It was, observes Berg, “one of the strangest processes I’ve ever been involved in.” Black Rebel Motorcycle Club ended up being a mishmash of tracks, cobbling seven songs from B.R.M.C.’s demo sessions together with six others cut after signing to Virgin. Released in April 2001—significantly, before the major-label bows from the Strokes and White Stripes—B.R.M.C.’s incendiary debut may well be regarded as the first shot fired in the “Rock Is Back” revolution.

“The trick about the first record was we were given creative control in the contract, signed for that [very reason], but it just seemed to be some words written down on a piece of paper filed away somewhere,” says Turner. “We got a head start, making part of the record on our own. Got a lot of it done without any questions. But somewhere along the line with A&R … their faith and trust all started waning.”

If the rise was meteoric, the band suddenly found itself cramming all its dues-paying into a series of pitched battles with Virgin. “It got ugly and was difficult,” says Turner, “and I felt a lot of the album was wasted energy on fighting and trying to keep the dogs at bay.”

Says Berg, “Our conversations and stalemates had more to do with the fact that they just didn’t want another opinion.“

“We were figuring things out in our own time,“ says Hayes. “It’s like, ‘Why jump into perfection just because you can, with someone who already knows what he’s doing?’ It’s not all that interesting. There’s no journey for the band that way.”

Spend enough time with B.R.M.C. and you’ll understand the paramount importance of this “journey.” They are—to steal from one of their songs—in love with something that they can’t see: a distant, abstract dream about themselves, their music and what both might become.

Like all dreams, this one fiercely resists verbalization which may explain why voicing promo platitudes in an unfamiliar room is especially galling. By the same token, trying to articulate their ephemeral visions to anyone outside the group is an effort hindered by a solid language barrier.

“We don’t use words well to explain what we want,” admits Hayes. “That’s why we can’t work with a producer or other people in that sense: Because the words we use with each other don’t apply to other people. They don’t understand.”

Robert Turner: True Faith

Outside DMX, an exasperated Turner sits on the curb and cradles his head as if it’s about to explode. “Well,” he says somewhat ruefully, “I don’t think they’ll be having us back anytime soon.” Turner understands better than most the peculiar vagaries of the music business. His father, Michael Been, is a rock lifer, most notably with spiritual big-‘80s outfit the Call, while his mother is a Lutheran pastor—a strange parental combination by anyone’s standards.

Robert Levon Been (his middle name is in honor of Band drummer Levon Helm, while Turner is a stage moniker purloined from Mick Jagger’s character in Performance) was born in Santa Cruz, but grew up in the East Bay. His earliest memory is watching the labels of his dad’s records revolve on the turntable: the Clash, Smiths and, particularly, Joy Division. “I loved them at, like, age three or four,” says Turner. “They had these great, childlike melodies behind this dark wall. Maybe if I’d known what Ian Curtis was singing about, it might’ve freaked me out.”

Turner’s boyhood fascination with music quickly turned to adolescent resentment, the result of having a father on the road for the majority of his young life. “I missed most of his growing up,” says Michael Been, B.R.M.C.’s soundman and valued consigliere. “I was with him until he was five, then I went on the road for 11 years. He would come out on tour during vacations and stuff. But he would always have to go back. That was tough.”

The Call was revered by fellow musicians— counting Bob Dylan, Bono and Peter Gabriel as fans—but had a history of hard luck with labels and crippling legal battles with management. Viewed through the prism of his father’s decidedly difficult experiences, Turner’s take on rock ‘n’ roll wasn’t that of a glamorous, inviting lifestyle. “I saw it as a job—and a really hard job, at that,” he says. “And I didn’t want to have anything to do with it. ‘Cause I saw what it did to him. It was a trying, difficult life. And I didn’t really understand what music could be; I didn’t hear it in the same way. For lack of a better word, I rebelled against it.”

This rebel stance would soften when a teenaged Turner heard Ride’s “Leave Them All Behind” for the first time. “That turned my head completely around,” he says of the seminal shoegazers. “It was like having new eyes and new ears.” The revelation of Ride would open doors to the Pixies, Stone Roses, Verve and further back to the Rolling Stones, Velvet Underground and Neil Young. Spurred by these discoveries, Turner picked up a bass in junior high. His father’s only advice was, “Don’t take any lessons.”

Like Jago, Turner’s teenage ennui was worsened by his parents’ divorce, and he later experienced an eerily similar manic-depressive episode. Further aggravating his alienation were the years he spent at Acalanes High, where Turner felt disconnected from the wealthy and well-adjusted student body. One day between classes, Turner spied another self-styled loner, Peter Hayes, walking around with a guitar on his back.

“There was this girl I was into,” says Turner, “and I saw Peter trying to teach her how to play guitar. I thought he was hitting on her, and I was like, ‘Fuck him!’ So I tried interrupting. I don’t know what happened to the girl. She ended up fading away, but me and Pete stuck together.”

Hayes’ schoolyard-troubadour persona was no pose; he was already a professional musician. “Sort of,” laughs Turner. “He had a gig at this bar. It was just him and his effects pedals and electric guitar. This weird folk/psychedelic thing. It was terrible, but at the same time, there was something in it that was fucking great.”

Hayes’ knowledge of music was a strictly classical education: Hendrix, Floyd, Dylan and old folk and country. Turner introduced him to his beloved post-punk and English bands, and the two began writing and recording a series of what Turner calls “fake Joy Division and New Order songs.”

An angsty reprobate with a rough past, Hayes was living out of his van by age 16, forced or kicked out of every place he’d called home, however temporarily. He would eventually move into Turner’s house, and the two would form a fraternal, intensely loyal allegiance—Damon and Pythias reborn as rock ‘n’ rollers—that neither of them can fully articulate. Like Turner, Hayes was a self-taught musician, resistant to formal structure and suspicious of the established way of doing anything. Together, they discovered strange tunings and developed a sound unique to their pairing. Shy and reticent, they didn’t venture onstage for years—“We weren’t ready,” says Turner—until forming the Wave.

Seattle, July 22, 10:31 p.m.

“Onleeee youuu! We came to see onleee youuuu!” Between the music blaring from the speakers and the chatter of the patrons, it’s damn near impossible to hear anything at Seattle’s Graceland bar. And so the two young Japanese girls talking to Robert Turner have to strain to tell him they’ve flown all the way from Tokyo—some 5,000 mile—to see B.R.M.C. play. They’re forced to repeat themselves several times. It’s not their broken English; it’s more that Turner can’t seem to comprehend they’ve traveled so far just to watch the band. Between late 2000 and early 2002, B.R.M.C. criss-crossed the U.S. six times, playing in excess of 300 shows. “Each time we went back,” says Turner, “the crowds would multiply.” Despite dogged roadwork and the steady critical acclaim that helped push the debut album past expectation in foreign territories, B.R.M.C.’s relationship with its record label was turning increasingly sour by early 2002. This was largely due to Virgin’s inability to capitalize on the overseas momentum here at home. “We wanted so badly to do well [in America]—we were trying so hard, but no one was helping us,” says Turner. “At the same time, we were one of the bands that was supposedly [spearheading] this new movement.”

Ultimately, B.R.M.C.’s dissatisfaction would result in a split with A&R man Berg, who left the label in February of last year. Two months later, sweeping personnel changes ushered in the administration of new Virgin head Matt Serletic, delivering the band a relatively clean slate within the company. But B.R.M.C.’s conflicts with the label were not without consequence. As a parting shot, Turner suggests the outgoing Virgin regime exacted some small measure of revenge by not manufacturing enough copies of the album to satisfy retail demand in the States. “There weren’t any records to sell for a long time,” says Turner. “Just recently are they starting to filter back in stores. That really hurt.”

Of more pressing concern was the Bush administration’s toughened post-9/11 immigration policy, which meant Jago—whose U.S. visa status had been murky at best—would have to return to England indefinitely. (The band ended up playing a handful of dates with Verve drummer Pete Salisbury sitting in.)

In a show of solidarity, Hayes and Turner decamped to Britain late last year, joining Jago there to record their second album. Their extended visit in the U.K. coincided with their ascent as bonafide superstars in that country—appearing on magazine covers, opening stadium gigs for Oasis—as album sales passed platinum status. This success finally reverberated back to these shores, with the videos for “Whatever Happened To” and “Love Burns” getting mainstream exposure via MTV.

Work on B.R.M.C.’s sophomore album commenced late last year at Mayfair Studios in London. The band spent eight days there recording rhythm tracks before taking the tapes to The Fortress, a tiny, $35-a-day rental room where the album was completed in splendid isolation. Given the band’s demanding tour schedule, it’s no surprise the bulk of Take Them On, On Your Own was written on the road—sometimes at soundcheck, more often during actual performances. Opening track “Stop” (“We don’t like you, we just want to try you”) was improvised live in London, born out of the bass coda to “Fail-Safe” (from last year’s Screaming Gun EP). Similarly, “Heart + Soul” was pieced together from a series of onstage explorations of “Salvation.”

Take Them On is a brutal and invigorating assault, its railing guitars and propulsive rhythms leaping from the speakers. More significantly, the group’s strengthened sound has been partnered with combative lyrical imagery. As B.R.M.C. willingly admits, its debut was childlike, almost elementary in its themes, littered with cardinal questions (“Whatever happened to my rock ‘n’ roll?”) and strewn with religious imagery (“Jesus, when you coming back?”).

“Those are simple questions—of religion and faith—but they’re usually the first thing to be lost and forgotten,” says Turner. “The first album was universal in that way—we were trying to be embraced or embrace people. We weren’t ready for anything more. It didn’t really instigate or point fingers. With the new album, it was time to draw a line in the sand and not be afraid of what it means to put your neck out.”

Many of the new songs (“Stop,” “Six Barrel Shotgun,” “Generation”) read like poison-pen letters to B.R.M.C.’s latecoming, MTV-fed followers, while others are piercing personal laments (“Shade Of Blue,” “Rise Or Fall”) or anti-imperialist rantings (“U.S. Government”). For a band like B.R.M.C. to turn to an audience of twentysomething contemporaries and spit something as direct as “I don’t feel at home in this generation” or metaphorically loaded as “I’d kill you all, but I need you so” is a calculated risk. Hayes had his own doubts about the songs during their public unveiling at a London show last December. Says Turner, “He said, ‘I don’t know if I can do this. I don’t know if I can say that [stuff] and look people in the eye.’”

These concerns have been erased by the time the band reaches Seattle’s Graceland. Under a battery of white-trained light, Hayes delivers the new material with an unreal fervor, while Jago loses all restraint lashing his drums. B.R.M.C.’s shared psychosis—all the pent-up alienation, confusion and suspicion—seems to come out in its music’s violent throttle. The set crescendos as Turner jumps into the crowd. A bright-blue spotlight catches the corona of his hair as he bangs away at his bass. “I’d kill you all, but I need you soooooooo.”

But what does it mean, all this sound and fury?

“Well, it means you really better believe what you’re saying,” says Turner. “Because that may be all you’re gonna have if it’s not understood.”

Peter Hayes: Complicated Situation

Sweat falls from a tendril of Peter Hayes’ hair as he bends down and begins reciting a stream of poetry: “Four and six have come and gone five times before this scene/And upon the lips of everyone a curse they’ve never dreamed.”

It’s 2 a.m., and Gracleand is almost empty as B.R.M.C.’s crew packs up the gear and the few remaining patrons are ushered out. Gripping his Jack Daniel’s neat and feeling no pain, Hayes steps in close again: “‘The young must be our sacrifice,’ they say with crippled grins/The eyes of youth must lose their way and stumble here within.” They’re lyrics to a new song, a Dylanesque fever dream Hayes has written called “Complicated Situation.” The title could serve as the perfect description of its author as well.

Among the members of B.R.M.C., Hayes is both the easiest to hang out with and the hardest to talk to. Much like Turner, when Hayes speaks, his words are separated by long … pregnant … pauses. (“I know what goes on in Peter’s head when he’s not saying anything,” says Turner. “That’s the real fucking story.”) Hayes isn’t into navel-gazing tedium; he doesn’t like analyzing the band, hates talking about himself. “Masturbation of the mind,” he calls it, but once you get him to let down his formidable guard, he’s among the most intriguing figures you’re likely to meet. Even those with whom his relationships have been rocky, like Tony Berg, will tell you: “Peter is this incredibly lovely, poetic soul—when he’s not suspicious of you.”

Perhaps it’s the haunted eyes or the street-urchin manner, but it’s tempting to view Hayes’ life as a redemptive Dickensian tale. Hayes’ birthplace, Martinez, Calif., is less than 30 minutes from the heart of San Francisco—but like the cliché goes, it might as well be a million miles away. Martinez is a harsh patchwork of manufacturing plants, refineries and industrial smokestacks. Although Hayes moved from there before he was old enough to walk, it’s clear that a part of that smoldering, dirty burg has never really left him.

Hayes’ father was a Brooklyn-bred tough with dreams of leaving city life behind for good. He uprooted his young family and moved to Minnesota— “Bob Dylan country,” as Hayes proudly puts it—to work on a 190-acre farm outside of New York Mills, near Brainerd.

“I cut wood for the winters, bailed hay, fed sheep, cows, the whole deal,” says Hayes, a bit of North Country drawl still present in his voice. In the morning, Hayes would walk down a half-mile driveway to catch a school bus. It was on these long rides to the city that he learned a crucial lesson about how the world was divided: farmers and townies, poor and rich, us versus them. Hayes has never really stopped thinking in these terms.

By the time he hit his teens, the bank had foreclosed on the family farm and Hayes returned to the Bay Area to live with his mother and grandfather. As he puts it, “One day, I just got bored and decided to pick up my mom’s acoustic guitar.” Hayes developed his playing style—a DIY collision of mutant blues and effects-laden lysergic trickery—spending hours alone in his room lifting licks from a stack of well-worn vinyl: Hendrix’s Smash Hits, Pink Floyd’s Ummagumma, the Stones’ Big Hits.

Age 16 is where the story gets a little fuzzy. There were struggles at home, problems at school and scrapes with the law. Hayes says he’d rather not get into details out of respect for his family—which is probably true, though you get the feeling he doesn’t wish to unsettle the ghosts of his past, either.

“He was having a hard time, living in his van,” says Turner. “I ended up offering for him to stay at my house because he didn’t have anywhere to go. And he accepted, but only to live in the driveway. He wouldn’t live in the house. He would park in the driveway and use the bathroom. That was the furthest he’d come. Because everywhere he’d been to stay he’d gotten kicked out of eventually—he was hot-headed then—and didn’t want to have that happen again.”

Hayes finally did move into the house, but only briefly. Right after high school, he loaded back out, traveling the country in his van and drifting in solitude for a time before returning to Northern California to work a series of manual-labor jobs. But eventually—inevitably—he came back to Turner, and to rock ‘n’ roll. “I don’t know who I’d be if I wasn’t in this band,” says Hayes. “I might be a mechanic who completely hates music. Maybe I would’ve turned into that guy.”

Such blue-collar fatalism is something of a pose. In reality, Hayes is an artist in the best, truest and most worn-out sense of the word. Although he claims to own only a few records and admits to having read even fewer books, he’s written enough himself—stories, poems, songs—to fill a small library. Talk to Hayes long enough and he’s given to conspiratorial diatribes—about the government, the church and the music industry. Even the success of B.R.M.C. hasn’t diminished his tendency toward an all-encompassing paranoia. “It’s the most contagious disease there is,” laughs Turner. “I was fine until I met Pete. That’s the truth. He’s getting better and I’m getting worse, but he’s still in the lead if you ask me.”

But that’s not the full story, either. Maybe the real Peter Hayes, the one most seldom glimpsed, is actually a kind of utopian philosopher. “Everyone says look out for number one,” he says. “Don’t trust anybody. Worry about yourself. All that shit. But I’d like to see if there’s another way you can do it, another way to live—in a community way. Through art, through magazines, through all those mediums.”

“It’ll be our undoing,” adds Turner, “but down deep, we’re just hopeless optimists. It might seem like a contradiction, but that’s how we feel. I’m never gonna let that die, and Peter will never let it die—the idea that things can be different. That they can be better. It’s worth saying.”

Back at Graceland, Hayes leans in one last time, offering up the final perfect stanza of “Complicated Situation.” He smiles, and you wonder how a man who refuses to reveal himself in life can give himself away so easily in his art. “Actually, I feel like giving more and more to the people around me these days,” he says. “Most people would say that’s a bad thing. ‘Don’t do that, you give too much of yourself away. You’ll end up wasting it.’ But I’d rather not live like that. I’d rather keep giving until there is nothing left.”

San Francisco, July 24, 4:33 p.m.

The tinted window of a long, black limousine drops down revealing a smooth, ebony face: “Hey, man, I’m supposed to pick up the Black Rebels. Y’all know where they at?” Joined by the same Virgin rep from Seattle, Turner and Hayes are hustling off to do a spot on Live 105, the Bay Area’s biggest alt-rock station. As the driver holds the door open, they look a little put off by the massive stretch job in front of them. B.R.M.C. has a standing rule against taking limos and has issued strict orders to the record company never to send them. Only once has this policy caused any problems—at a star-studded gala for Bono in New York. Somehow it felt like a faux pas to arrive at the red-carpet reception in a Ford Econoline van. But it’s too late to do anything about their ride today, so they hop in.

Sliding down into the deep leather seats, Turner removes his sunglasses and rubs his eyes. Hayes pours whiskey from a crystal decanter, lights a cigarette and peers out the window. It’s B.R.M.C.’s final day in America before the new album comes out, and every minute of the band’s time is accounted for. There are at least five photo shoots—including one atop the offices of a gay-porn Web site—and a dozen or more interviews, all this before the band even gets to its radio appearance. “This morning, a writer asked me if I was allergic to anything,” says Hayes. “Then he asks me if it’s true that I have a kid. I told him, ‘Today’s your lucky day. Since I’m in a good mood, I’ll just say that it’s none of your fucking business.’”

The media and marketing blitz is part of Virgin’s redoubled effort to break B.R.M.C. in America. Sales of the band’s debut have finally pushed past 100,000 in the U.S., a good showing but still lagging well behind the 400,000 units logged in the U.K. It’s an odd, if not wholly unprecedented, situation for an American group to be in.

Earlier this year, Virgin’s top brass had been pushing hard for Andy Wallace (Linkin Park, Limp Bizkit) to mix Take Them On, On Your Own. B.R.M.C agreed to a trial run, but after getting a sampling of Wallace’s work, they were devastated. “No offense to him, but for us it was … um … when it came out the other side, it wasn’t our band anymore,” says Hayes. “It sounded like every other band on the radio.” B.R.M.C. rightly worried it was about to witness a painful replay of its early struggles with Virgin. But with the support of new A&R man David Wolter, the band completed the mix itself with friend Ken Andrews (Air, Pete Yorn).

The elevator doors open into Live 105’s studios, where DJ Jared is waiting in the booth with his arms outstretched. The instant he greets them, you can sense impending disaster. Jared is one of those high-energy drive-time jocks, tossing zingers and cracking jokes. Generally, he’s about as funny as a small child with cancer. Virgin has tried to minimize situations like this for B.R.M.C., but to make it in the ruthless world of mainstream radio, on-air appearances and festival performances are necessary evils.

B.R.M.C. goes about the dirty deed with the enthusiasm of men approaching the gallows. They try to keep up with Jared’s hyperactive banter, but they’re ill-suited to radio: Droll humor and long gaps in speech translate to dead air, a jockey’s worst nightmare. Jared insists on asking about Jago’s visa problems, plays some snippets of the Call—anything he can do to goad them. At one point, he makes the mistake of needling Hayes. If no one else were in the room, you get the feeling Hayes might pop the mouthy DJ in the face. As it is, he juts his jaw and says nothing.

The 20-minute spot mercifully ends, and the band makes a hurried exit. In the elevator, the Virgin rep is unable to hide her frustration: “It’s kinda like pulling teeth with you guys.” Turner bites his tongue and mutters a curse under his breath. Back in the limo, they turn the radio on and hear Jared voicing a dog-food commercial before excitedly spinning the new 311 single, with the plug: “This is the sound of now!”

Clearly, there’s work yet to be done. But to those around the band, B.R.M.C.’s trans-Atlantic success has surpassed expectation, perhaps beyond what’s realistic. As leaders of the retro-rock class of ‘01, the hope is they’ll be able to compete on the same commercial level as their peers, even if they lack the raffish, pretty-boy charm of the Strokes or the novelty dynamic of the White Stripes. “It’s a different animal now,” says Turner of the band’s changed status. “[Virgin] actually think they can make money off us, which is a really bad place to be. Not in every way, but in a lot of ways.”

Whatever its concerns, B.R.M.C. has reached some kind of denouement with its label. Virgin seems resigned to let the band have its way, indulging it like a parent would a talented-yet-troublesome child. But it’s a talent that’s taking a hard stylistic turn. B.R.M.C. is already well into the writing of its third record, one that promises to be a career-defining departure. The material Turner previews on his laptop—demos for half a dozen new songs—is the sort of raw blues, scuffling country and liquid gospel that should finally end all the Jesus And Mary Chain namechecks and usher in a whole new set of comparisons to the Stones, Dylan and Sam Cooke. Creatively, B.R.M.C. is moving faster than anyone—the media, fans or its record company—can keep up with.

San Francisco, July 24, 10:37 p.m.

It’s a homecoming of sorts at 330 Ritch Street, tonight the site of Popscene—the same weekly convocation where Turner and Jago first hung out years ago. B.R.M.C. is the evening’s special guest. The tiny club is sold out, and there are hundreds of B.R.M.C. diehards still hoping to get in. It’s hot, crowded and the security staff is in no mood to deal with a bunch of rock fans. The simmering tension erupts when a bouncer, mistaking Jago for a fan trying to sneak backstage, strong-arms the wiry drummer. Hayes quickly leaps to his defense and nearly scuffles with a 300-pound monster wearing an “I Love Hip-Hop” T-shirt. “I know he could kick all our asses,” spits a livid Hayes. “So fuckin’ what?” Just before showtime, Turner dispatches one of B.R.M.C.’s road crew to gather those shut out of the show and sneak them in through the back door of the club. A small army of fans comes charging up the alley before a truly pissed contingent of security puts an end to the whole scheme.

B.R.M.C. takes the stage after midnight, storming on with standard opener “Spread Your Love.” Spirits are high, and Hayes cracks wise: “Hey everybody, don’t take the brown acid.” But it’s less Woodstock than Altamont tonight. Fights are breaking out left and right. Caught in the middle of the chaos, Michael Been stands firm at the console trying desperately to hold the sound together. The band ends with a vicious noise manifesto that evolves into a gorgeous, flowing jam—and perhaps a new song—with Turner barking improvised lyrics.

Post-show, Turner finds a quiet corner and spends an hour talking to his mother, while the others chat with fans before boarding the waiting tour bus. The members of B.R.M.C.—Turner especially—seem worried they’ve lived up to a stereotype they’re trying hard to shake: the portrait of the group as featured on an NME cover not long ago, bearing the hyperbolic headline “Drugs. Death. Paranoia.” Says Turner, “All those things are a part of us, but they don’t rule our lives. If it were true, we’d be strung out or dead or so paranoid we couldn’t get out of this room.”

Among the many words associated with B.R.M.C., the one that comes up least frequently is love. Yet in a way, it’s what drives and defines the band. It’s what Turner sees in Iggy Pop and Neil Young—heroes and role models to B.R.M.C.—as the intangible quality that endows greatness. “They have such a pure love for what they do, and it shines through,” he says. “But it isn’t cheesy. It’s dark and intense. It’s romance and passion and dirt and grit all mixed together. I don’t see that in any new bands. And maybe you have to come from a time where you knew what the world was like without rock ‘n’ roll to be like that. I dunno. People always ask what we want out of the band: money or fame or girls. But that’s not what we want. We want that love. We want to get it, to find it somehow.”

With that, Turner hops aboard the coach, and B.R.M.C. rolls off into the night to continue the search.