Radio City Music Hall, 1985: It’s the second annual MTV Video Music Awards, and host Eddie Murphy is in the middle of his opening monologue. As the leather-clad comedian scans the famous faces in the audience—Cyndi Lauper, Huey Lewis, Corey Hart, Wang Chung—Murphy marvels at the assemblage of big-name talent and unloads a line that gets the night’s biggest laugh: “Man, if someone dropped a bomb on this place, Glen Campbell would be the biggest star left in the world.”

It’s a measure of the colossal success he’d tasted that Campbell could laugh off such a cruel jibe. After all, he’s forgotten more of fame and fortune than anyone in that audience could possibly dream of. Once a star of stage, screen, radio and record, Campbell—at the peak of his popularity in the late ‘60s—had been bigger than the Beatles.

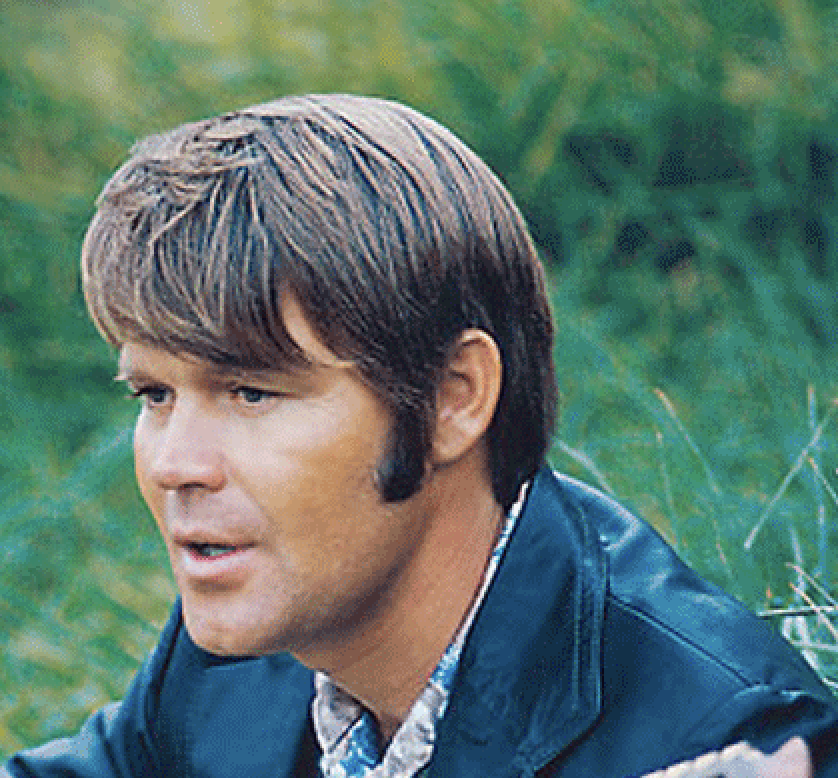

Today, he leans back into a white sofa in his elegant Scottsdale, Ariz., manor. Tanned, thin and still cherubic at 67, Campbell has invited MAGNET into his home to discuss the long overdue boxed set of his work, The Legacy [1961-2002] (EMI/Capitol), which collects the material that helped earn him 17 gold and platinum albums and nearly 50 million in record sales.

Such dizzying heights of pop success are a long way from the Arkansas backwoods where Campbell was born the seventh son in a family of eight boys and four girls. Before he’d turned 10, Campbell was a guitar prodigy who saw music as an escape from a harsh, penurious life of farming. “Me and manual labor didn’t get along at all,” he says. “‘Cause I had to do so much of that when I was a kid: pick cotton, gather corn, look a mule in the butt all day drivin’ a cultivator for Daddy. As (country singer) Roger Miller used to joke, ‘They were so poor, they had to jack off the dog to feed the cat.’ Well, we were in the same boat.”

Campbell lit out from home at 16 to join his uncle’s honky-tonk band in New Mexico. Later fronting his own outfit, he worked the Southwest’s dance and bar-band circuit for eight years, becoming a regional success with weekly radio and TV shows. In 1960, the 24-year-old Campbell decided to take a gamble. With only his young bride and a few hundred dollars in savings, he left Albuquerque and headed for Hollywood. Fate smiled on the plucky guitar picker as he quickly fell in with a crowd of rock and pop movers, working on sessions for teen idol Rick Nelson, landing a spot playing guitar for the Champs (of “Tequila” fame) and signing on as a staff songwriter at publishing house American Music, where he launched his career as a solo artist.

The Legacy digs deep into the archives, kicking off with Campbell’s debut 1961 single, “Turn Around, Look At Me,” a fluttering, string-laden balled that earned him an appearance on American Bandstand. The next year, Campbell signed to Capitol, where he scored minor success with a variety of styles—such as the bluegrass gallop of “Kentucky Means Paradise” and the halting folk of Buffy Sainte-Marie’s “Universal Soldier.” He even recorded a sad surf/pop gem called “Guess I’m Dumb,” penned by Brian Wilson; Campbell also stood in for Wilson on the road with the Beach Boys in 1964-1965.

Despite these passing attempts at a solo career, Campbell largely remained a sideman, becoming a member of legendary L.A. session collective the Wrecking Crew. In 1963 alone, he appeared on more than 500 recordings. He spent the bulk of the decade working with the era’s biggest names—Elvis, Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Phil Spector, Sam Cooke, Dean Martin—his fluid, ringing guitar gracing everything from Pet Sounds to “Strangers In The Night” to the Monkees’ “I’m A Believer.”

It wasn’t until 1967 and Campbell’s blithe, banjo-backed reading of John Hartford’s “Gentle On My Mind” that he finally struck gold as a solo artist. The same year, Campbell made a fateful discovery in the songs of Jimmy Webb. An Oklahoma-born minister’s son turned shaggy-haired hippie tunesmith, Webb was riding high on the success of “MacArthur Park,” which he’d written and arranged for actor Richard Harris. “When I heard that, I felt a connection,” says Campbell, “I thought, ‘I know where he lives. I gotta get together with this guy.’”

The Campbell/Webb pairing would prove one of the era’s most successful, producing a clutch of sweeping, melancholy classics (“By The Time I Get To Phoenix, “ “Wichita Lineman”) and subtly subversive narratives (“Galveston,” “Where’s The Playground Susie”). Campbell’s crystalline croon and drop-tuned Danelectro guitar solos gave the songs a distinctive stamp. His crossover appeal was confirmed at the 1967 Grammys, where Campbell became the first person to win awards in both the pop and country categories.

The following year, the Smothers Brothers tapped him to host a summer replacement for their variety series, which resulted in The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour. An instant smash, the show catapulted the singer into a rarefied stratum of sales and superstardom. “I already had four or five albums out, so when the TV show hit, I had all of this product available—and that’s how you sell 50 million albums,” says Campbell. “After the TV thing happened, it was madness.” Indeed, Campbell blew up into a multimedia sensation overnight, even starring in one of the year’s top box-office draws, True Grit, with John Wayne. By the end of 1969, Campbell’s records were outselling the Fab Four’s.

This white-hot streak didn’t last forever, though, as Campbell’s variety show limped to a finish in ‘72 (“We might’ve been on too long,” he admits), its demise coinciding with a decline in his chart fortunes for the next few years. But Campbell’s knack for finding and shaping hit-worthy material would help him burn bright throughout the second half of the ‘70s, with a comeback that included songs such as the signature “Rhinestone Cowboy” and a chart-topping version of Allen Toussaint’s “Southern Nights.”

But the strain of touring, a dependence on booze and the overwhelming pressure to replicate past successes were beginning to tear Campbell apart at the seams. After 17 years on the label, he parted ways with Capitol in 1979. “And I didn’t leave on a good note,” he says. “Some guy came in as president who didn’t know anything. I was doing an album of Jimmy Webb stuff called Highwayman, and I wanted the title track to be the single ‘cause I thought it could be big. He wanted me to do stuff like the Knack’s ‘My Sharona.’ So I promptly told him what he could do with his ideas.” (The upshot came eight years later, when Campbell brought the song “Highwayman” to the attention of his Phoenix neighbor and friend Waylon Jennings. Eventually, Jennings, along with Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson, would form a supergroup named after the song and turn the tune into a country-music hit.)

By the early ‘80s, Campbell’s career and personal life were spiraling downward. As record sales slumped further (“It became really hard to find good material,” he says), he became tabloid fodder after a coke-fueled, conflict-plagued romance with 20-year-old country vixen Tanya Tucker. A physically and mentally ravaged Campbell decided to escape the temptations of Los Angeles and headed for the desert.

Becoming a born-again Christian, Campbell married for a second time and witnessed the birth of two children (a daughter from his first marriage, Debbie, often performs with him live). The ensuing years found him making regular appearances on the country charts and cutting religious albums before he found a new career in the Branson theater circuit.

Sadly, the years somewhat obscured Campbell’s musical reputation, casting him as a prosaic middle-of-the-roader rather than a hotshot instrumentalist and peerless song stylist—even as artists like R.E.M., the Pernice Brothers, Mark Eitzel and the Tindersticks cited his influence. Exacerbating this was Campbell’s back catalog, which remained largely out of print aside from a few shoddy hits compilations. In the late ‘90s, EMI/Capitol finally began reissuing some of Campbell’s albums as two-fer packages before gathering the 80 hits, rarities and live cuts that make up The Legacy, a compelling omnibus that should help remind, if not fully restore, Campbell’s iconic status among pop aficionados.

As Campbell eases into retirement, he hints that the possibility of cutting an album with old foil Webb may push him back into action one last time. However he decides to close his career, Campbell can look back at a remarkable journey that’s taken him far away from his dirt-farmer roots. “I really believe I’ve had a hand in guiding my life that was special,” he says. “It’s the way God planned it for me. Even with all the highs and lows, I have no regrets about anything.”

—Bob Mehr