There is a phrase—the ‘sparkle factor’—in surfing that T describes the glistening effect the sun has on the water as it furls and trundles. The intense, rolling twinkle of refracted light is strongest in the early morning and late afternoon when the sun is at its sharpest angle in relation to the waves. At such moments, to be padding down the beach or poised in the surfing lineup out where the water begins its swell formations is to be privy to the sublime. The only sight more intoxicating—and privileged—is that of the ‘sparkle room,’ that is, the inside of the curl as the board traverses the long line of a Malibu-style wave. And the sole thing better than the sparkle room by day is the sparkle room lit by a full moon, the beauty of its fierce brevity tempting some to madness. The elemental lure of the sun was pleasure enough for the average seeker, but others would settle for nothing less than the sparkle room or its simulated equivalent. And that became a problem because no sparkle room could be expected to last.”

—Timothy White, The Nearest Faraway Place: Brian Wilson, The Beach Boys, And The Southern California Experience

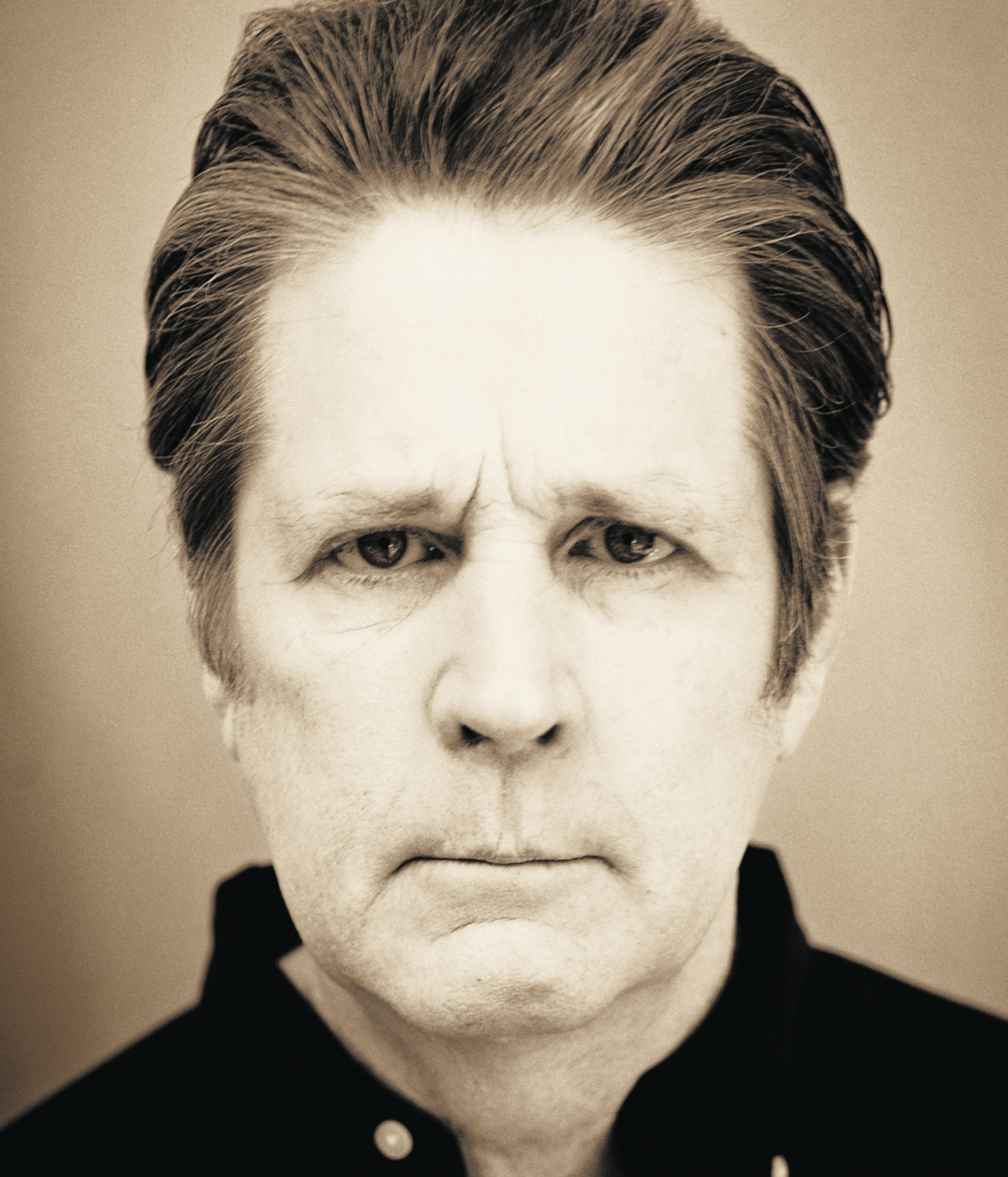

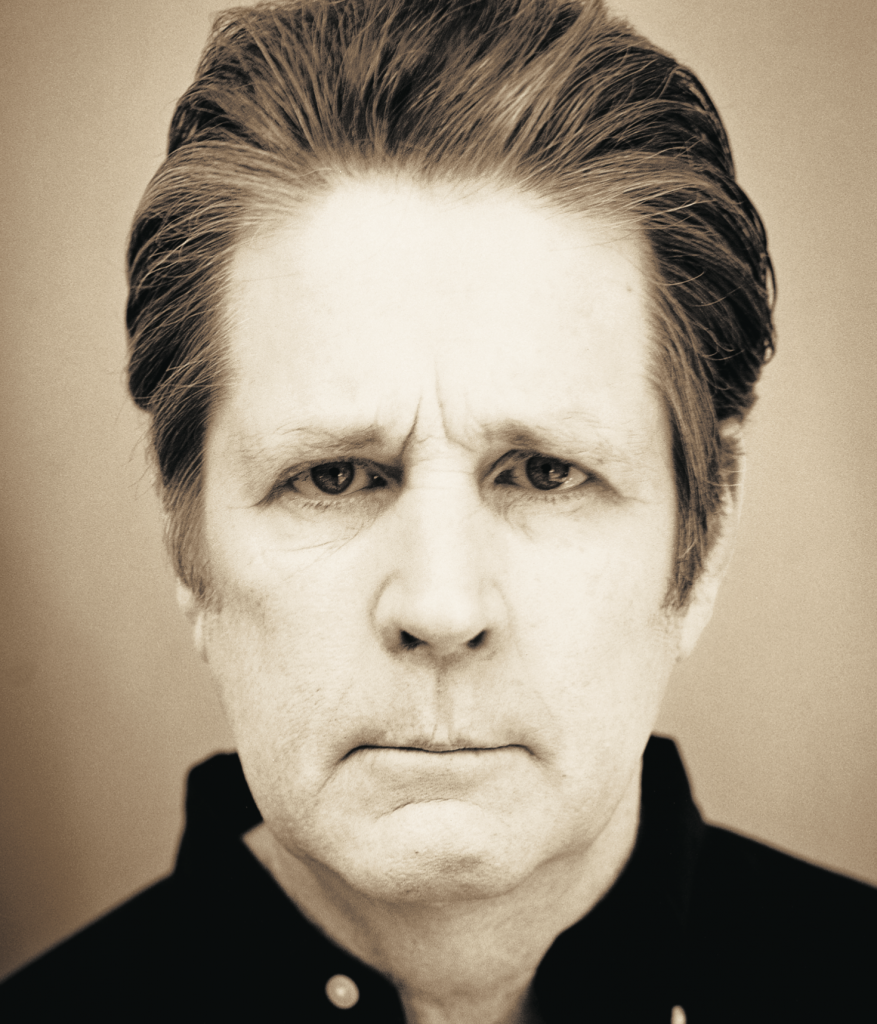

Teenage symphonies to God. That’s the phrase Beach Boys auteur Brian Wilson used to describe the divine music he was creating in the mid-’60s, when his compositional powers were achieving miraculous states of beauty even as his fevered faculties skirted the fringes of madness. With 1966’s Pet Sounds, his orchestral-pop opus of ocean-blue melancholia, Wilson clinched his status as teen America’s Mozart-on-the-beach. Less than a year later, he would fall off the edge of his mind. Years and years of darkness followed, and while he would later recover some measure of his sanity, Wilson would never again craft a work of such overarching majesty.

The Beach Boys were the first superstar pop group to rot on the vine. Their career arc is a gilded string of sunny hits, beatific smiles and high-tide evocations, followed by fallow decades of greed, bloatedness, beards and precipitous creative decline. Eventually, the Beach Boys morphed into a de facto oldies band, peddling the nostalgia of their own glorious and irretrievable youth. A fish, as the saying goes, rots from the head down—and Brian Wilson was indisputably the Beach Boys’ head. He wrote, arranged, produced and recorded nearly every second of sound from the band’s golden age, which gave rise to a mantra that was repeated endlessly in his proximity: Brian Wilson is a genius.

Today, it’s probably more accurate to say Wilson was a genius—a former genius the way Gary Coleman is a former child star. You see, Wilson’s genius years—roughly 1965-68, a period that spans Pet Sounds, “Good Vibrations” and the ill-fated Smile—were trailed closely by his mad years, which, it could be argued, covers just about every year after that. The border between the two eras is indistinct, and by 1967, the annus mirabilis of psychedelia, his genius period and his mad period bookended the same calendar year.

By Wilson’s own admission, his genius period commenced on that day in 1965 when he dropped acid for the first time and blasted himself into the cosmos where, he would later say, he came face to face with his maker. The chart-topping string of pitch-perfect odes to the endless summer of surfer girls and little deuce coupes gave way to a deeper, more mysterious and altogether holier music. You have to remember that this was during a time when pop stars were expected to be poets and seers. Like the Beatles during those heady days of the mid-’60s, Wilson was pushing pop music into the realm of high art. Leonard Bernstein said as much in a 1967 television documentary that featured Wilson, long-haired and cherubic at the piano, performing a transcendent version of “Surf’s Up.” All these years later, it’s hard to fathom that Wilson was only 24 when he wrote Pet Sounds.

Ineffably sad and sublime, Pet Sounds was considered a commercial failure upon its release in 1966—a little too hip—but it continues to speak to emotional seekers. By this point, Wilson had retreated from the concert stage into the role of pop scientist obsessively tinkering in his laboratory of sound. The Beach Boys’ golden throats were his instrument, and he made their honeyed harmonies sound as pure as a sunbeam. Wilson even brought in Tony Asher, a writer of commercial jingles, to pen lyrics for the album. Spurred to greater ambition by his admiration for and sense of competition with the music of Phil Spector and the Beatles, Wilson applied his trademark palette of swooning harmony and lush orchestration to create a classic song cycle of heartache and regret.

Pet Sounds was followed by the landmark “Good Vibrations” single, dubbed by critics a “pocket symphony” for its seamlessly interconnected suites. With its dramatic, zigzagging shifts in texture and rhythm, the song would forever alter the architectural design of pop music and serve as a template for Wilson’s ensuing arrangements. He began collaborating with Van Dyke Parks, another tender-aged brainiac with a gift for taking language beyond direct meaning and into the realm of deep suggestion. Serious magazines sent writers to hang out and write long thinkpieces about the new consciousness of the youth culture.

“[The lyrics] went from ‘ding witty pearl hang-ten’ to … ‘columnated ruins domino,’” Parks said in 1985 documentary The Beach Boys: An American Band. “Mike Love said to me one day, ‘Explain this: “Over and over the crow cries uncover the cornfield.”’ And it was an American gothic trip that Brian and I were working on, and I said, ‘I don’t know what these lyrics are all about—if they aren’t important throw them away,’ and so they did.”

But even as the accolades were piling up, Wilson’s behavior was becoming increasingly erratic. Fueled by Herculean quantities of dope and outsized visions of pop grandeur, his every flight of fancy was indulged no matter how bizarre or ridiculous. To create the proper mood and setting for work on his follow-up to Pet Sounds (an album with the working title of Dumb Angel but later retitled Smile), Wilson had a giant sandbox erected in his living room so he could sit at the piano with his feet in the sand. That the Wilson family cats would routinely mistake the sandbox for a litter box is a fitting signifier for the confusion and decadence that surrounded the recording of Smile. As the hours and hours of far-out snippets of sound piled up— pieces of a vast puzzle Wilson could never quite figure out how to put together—he grew increasingly irrational and superstitious. Eventually, he threw up his hands, retired to his bedroom and more or less didn’t come out for years.

When the plug was finally pulled on the Smile sessions, after months of pre-release hype and public anticipation, Wilson sank into a state of crippling depression, paranoia, addiction and obesity, spending most of his time in bed or in his bathrobe. He later reclaimed some measure of his health and sanity, thanks to radical interventions from psychiatrists and a cornucopia of anti-psychotic and mood-altering medications.

In his absence, Pet Sounds was rediscovered and, in many corners, hailed as pop music’s crowning achievement. At the same time, the mystique surrounding Smile grew to a fever pitch, fueled in part by the fact it was never finished or properly released. Today, Smile exists only in outtakes, available in part on the Good Vibrations boxed set and bootlegs. Short of actually hearing it, the enigmatic vibe of the music can be recreated by holding up a dollar bill and staring at the spot where the pyramid meets the eye. Though frustratingly incomplete and marked by a morose weirdness, the music exudes a certain cryptic significance. In short, it’s a brilliant mistake. Which is why Smile remains a dark, enduring curiosity: a source of abiding fascination for succeeding generations of fans wondering what could’ve been and musicians trying to connect the dots. Like the mysterious leopard found frozen to death near the summit of the mountain in Hemingway’s The Snows Of Kilimanjaro, everyone wants to know how Wilson got that high and what he was looking for up there.

In the face of all those lofty question marks, Wilson maintained a sphinx-like silence, unwilling or unable to talk about the project. Given its central role in his downfall, it’s no wonder Wilson refused to even discuss the album in interviews, let alone entertain repeated entreaties to finish and release it. As of late, Wilson seems to have had a change of heart. He’ll be performing the album live in England in February and March, with plans to release a live album of the Smile tracks in the fall. He’s currently putting the final touches on a new studio album, slated for release in the spring.

There have been several “Brian Is Back” publicity campaigns over the years, followed by middling albums and disappointing tours. But these days, Wilson seems to be enjoying one of the most focused and productive periods since his fall from grace. He performs regularly, although there’s an unnerving robotic-ness to his stage presence. In conversation, he seems lucid and relatively happy—married again, with a new family—but he tends to stick to the script. MAGNET interviewed him in 1999 and again for this article, and even though the questions changed, the answers stayed the same: “Phil Spector is God.” “The Four Freshmen taught me harmony.” “We prayed that we would bring into existence an album that would make people feel love.” The only real difference between the two conversations was his assertion that Michael Jackson was set up and there’s no way Phil Spector did it.

Even as the legend of Brian Wilson The Genius looms larger and larger, the man himself seems somehow diminished. He no longer has the Beach Boys’ voices to carry his tunes—brothers Carl and Dennis are deceased, and his relationship with Mike Love has devolved into bitterness, acrimony and litigation. Wilson’s own voice, tarnished by years of excess and neglect, is now a bare, ruined choir of one. However, he’s now backed by an exceptionally fluent 10-piece band that can replicate those early Beach Boys harmonies and recreate Pet Sounds down to the last sonic detail.

Onstage, they form a lush, precise music machine that cloaks Wilson in a Disneyesque bubble of sound. He may no longer be able to hit those angelic highs, but just to be able to sit with the man as his profoundly sad and beautiful music takes wing on a balmy summer breeze is godsend enough.

Sail on, sailor.

—Jonathan Valania; photo by Sean Shroff