Twenty years ago, Mudhoney made Superfuzz Bigmuff, the landmark recording that launched grunge and put Seattle on the musical map. Here’s what really happened.

Who’s Who In the Mudhoney Story: Jeff Ament (Mother Love Bone bassist); Mark Arm (Mudhoney singer/guitarist); Nils Bernstein (journalist, record store owner); Jennie Boddy (Sub Pop publicist); Ed Fotheringham (illustrator, Thrown Ups singer); Stone Gossard (Mother Love Bone Guitarist); Jay Hinman (journalist, fan); Steve Manning (fan); Thurston Moore (Sonic Youth singer/guitarist); Bruce Pavitt (Sub Pop co-owner); Dan Peters (Mudhoney drummer); Charles Peterson (photographer); Jonathan Poneman (Sub Pop co-owner); Bettina Richards (Atlantic Records A&R person); Steve Turner (Mudhoney guitarist)

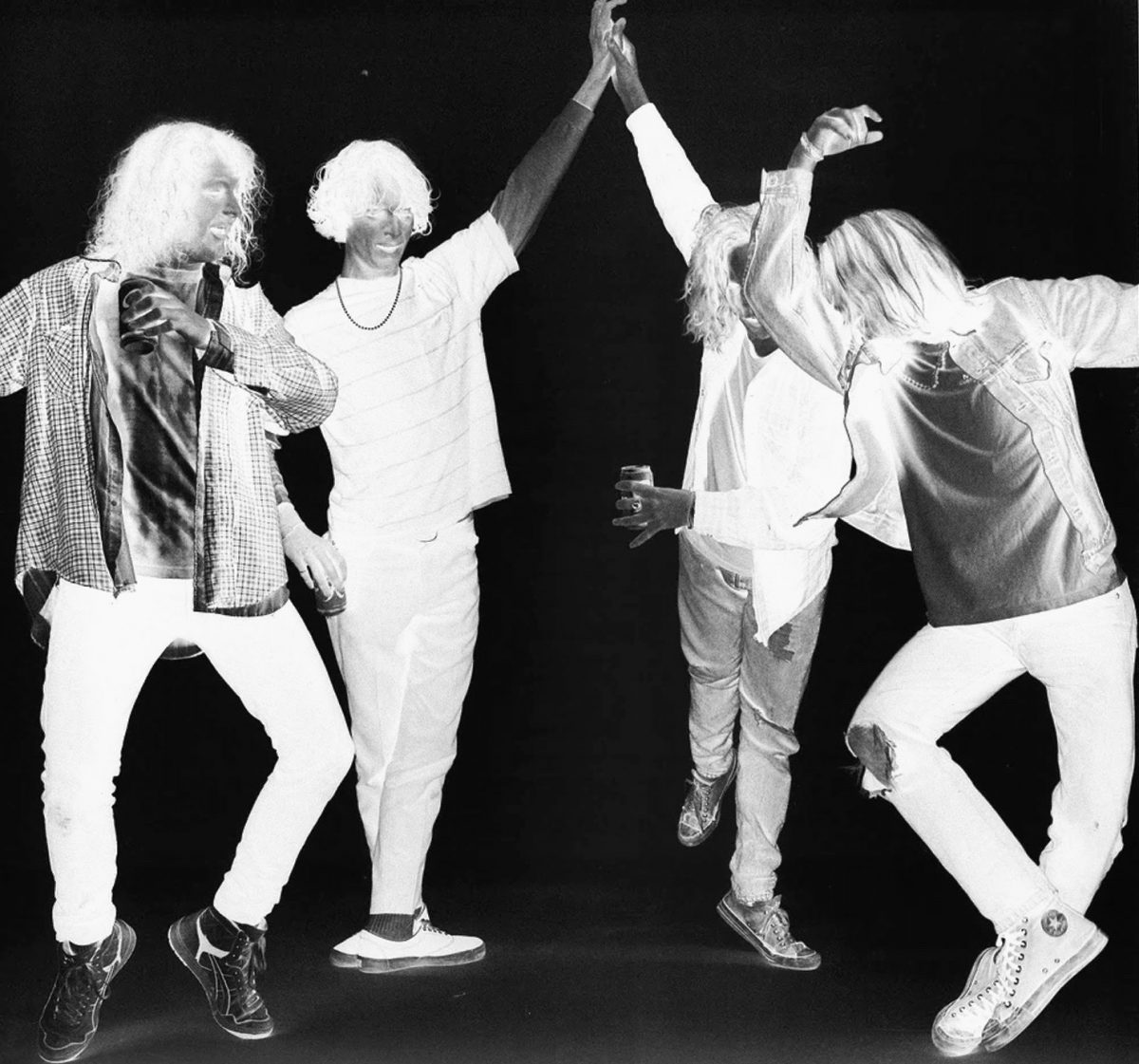

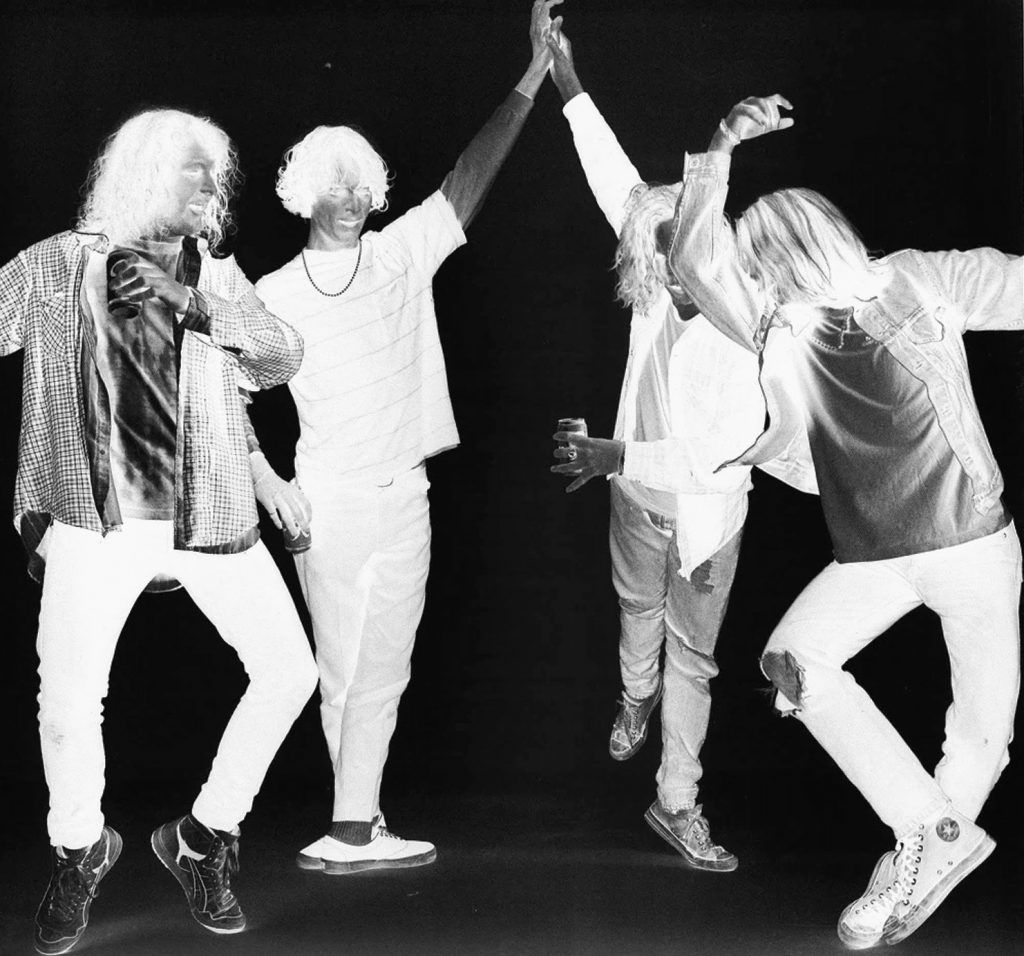

Before everybody loved them and everybody loved their town, the guys in Mudhoney were just another group of Seattle music-scene misfits and castoffs. At the beginning of 1988, the phrase “Seattle music scene” didn’t have quite the same meaning as it does now. Singer/guitarist Mark Arm, guitarist Steve Turner, drummer Dan Peters and bassist Matt Lukin ushered in the grunge era with the August ’88 release of “Touch Me I’m Sick,” Mudhoney’s debut single. The snotty, motorized garage-rock blast wasn’t exactly a shot heard ’round the world, but it was heard by the right people, and the subsequent Superfuzz Bigmuff EP, issued two months later, cemented the gloriously sloppy sound and beer-goggled vision that would make some other people in Seattle (Nirvana, Soundgarden, Pearl Jam) very famous.

The members of Mudhoney were like the Monkees, except they were all Peter Tork. Their perpetually drunk, stoned and dumbstruck shtick belied the acumen of four gifted musicians, true rock ’n’ roll believers and world-class smartasses. On the 20th anniversary of Mudhoney and the founding of the local record label it helped get off the ground, Sub Pop has released Superfuzz Bigmuff: Deluxe Edition, a two-CD reissue of the original artifact, plus demos and live recordings from 1988.

Concurrently, Sub Pop has released Mudhoney’s eighth studio album, The Lucky Ones. Though Lukin retired from the band in 1999 (he could not be reached for comment for this story), Arm, Turner, Peters and bassist Guy Maddison clearly aren’t running on fumes; The Lucky Ones opener “I’m Now” finds Arm wailing, “The past made no sense, the future looks tense,” riding a sweet fuzzbox guitar riff, as gloriously confused and confusing as Mudhoney ever was.

MAGNET’s oral history of Mudhoney’s first 18 months begins with Arm and Turner opting out of Green River, their band with Stone Gossard and Jeff Ament, who’d later go on to form Pearl Jam.

Steve Turner: I met Mark in 1982 when he was just a punk who went to my high school. He had a mohawk, a kilt and big boots with bandanas wrapped around them. He was straight edge and so was I, at least theoretically. I was really into Minor Threat and discovered that, “Wow, there’s other kids out there like me that aren’t fucked-up punks.” We were all in line for a TSOL show in the fall of 1982, and [a mutual friend] introduced me and Mark. He introduced us to each other as both being straight edge, and we both rolled our eyes … [In 1984], me, Mark and Jeff Ament had formed Green River with Alex Vincent, and then Stone Gossard joined a few months later. I quit about a year after that. I just didn’t like the music. They were growing their hair long, and I shaved my head. They were wearing makeup, and I didn’t want to do that. I thought we were still a punk band, but then we weren’t. I was really into the Replacements and wanted to be a fun punk band, but along the way it got metalized.

Mark Arm: Steve quitting Green River was a wake-up call. We had this West Coast tour set up. The second-to-last show was in San Francisco, and I blew out my voice. The next night we went to L.A. and opened up for Jane’s Addiction, and I think Jeff had reached out to some people in the A&R world. Expectations were, “Hey, we can show off our talents to these people and maybe even get signed!” Of course, I’d totally fucked myself the night before. I had a one-or two-note croak, and I’m not a great singer to begin with. Jeff and Stone thought I would hold them back from realizing their dream. As history proves, they made the right move.

Nils Bernstein: Green River was a fantastic band, but there was tension between Mark’s irreverence and refusal to pander to the audience, and the band’s ambition to do something more varied and classic-sounding.

Charles Peterson: With Green River, Mark had been forced into trying to be the lead singer of a glam band—or a band going in the glam direction. Toward the end, he was just going through the motions; it didn’t suit him.

Arm: From my perspective, I got the boot from Green River. I contacted Steve, who at that point was going to school up in Bellingham at Western Washington University, and was like, “Hey, if you ever wanna start another band, I’m available.”

Turner: I dropped out of college and moved back to Seattle, and me, Mark and Dan Peters started practicing.

Arm: We started getting together in November (1987) and had heard that Matt Lukin was leaving the Melvins or being left behind by the Melvins; we weren’t sure of the story. I’d known him since the days of an all-ages club in Seattle called the Metropolis, which would have been around ’83 or ’84. We asked if he was into playing bass with us, and he was like, “Sure, why not?” He was coming to Seattle for New Year’s Eve.

Turner: Matt had been going to school to be a carpenter, and that’s what he does to this day. Dan was the youngest in the band when we started. He was 21; the rest of us were a few years older.

Dan Peters: We went to see a Motörhead and Alice Cooper concert for New Year’s Eve. Nobody knew that Motörhead had cancelled, so we ended up having to sit through a bunch of bands like Faster Pussycat and Armored Saint. I couldn’t take it anymore, so I had to leave even before I saw Alice Cooper.

Arm: The very first practice with all four of us was New Year’s Day, 1988. That’s where we mark the birth of the band. That’s our anniversary date.

Peters: The next thing we know, Matt’s driving up from Aberdeen every week or so. We went into the studio and recorded a batch of songs before we even played a show. We knew that we could at least put out a single with Sub Pop because they had just started up and we knew they were interested in the band.

Bruce Pavitt: Before I did Sub Pop full time, myself, Mark Arm and Jonathan Poneman all worked for a foreground music company, Yesco, that later got bought out by Muzak. It was just a steady job with benefits. A lot of the grunge crew worked there. I remember Mark came in, maybe in January of ’88, with a tape and he said, “I started this band Mudhoney.” The first song was “Touch Me I’m Sick.”

Bernstein: I have a clear memory of sitting in a friend’s truck with Mark one night, and him saying that he was going to form a band with Steve again, and it was going to be the greatest band in the world. That would sound dorky in retrospect were it not for the fact that their first single was actually one of the great debut singles of all time: a totally complete, infallible musical statement. I remember thinking, in the truck, that the way Mark talked about Steve was really sweet, almost wistful. There were so many influences they shared that neither of them was doing much with musically at the time, whether it was heavy Australian stuff like Feedtime and the Scientists or San Francisco and Texas hardcore or Billy Childish.

Turner: There really wasn’t much of a scene at that point. Seattle was basically the dregs of the punk-rock scene. Sub Pop released some early Green River and Soundgarden stuff, then they actually got an office. Jonathan Poneman came aboard (Sub Pop) about the time we were forming.

Bernstein: Most of the early grunge bands had been around for a while before everything took off: Green River, Soundgarden, the Melvins, Bundle Of Hiss, Malfunkshun, Skin Yard, etc. So to Seattleites, Mudhoney was kind of a supergroup: the “punk” half of Green River, the bass player for the beloved Melvins and the best drummer in Seattle. Even before their first show, there was no question that they were going to be amazing.

Pavitt: [Sub Pop] didn’t have a lot of prospects for the future. At that time, our big release was Rehab Doll by Green River. We had put everything we had into that release. Right around the exact day that we opened the office, Green River called to notify us that they had broken up, so that was an awkward place to be. Our big release was by a dead band, so we were hoping that Mudhoney would turn into something worthwhile.

Arm: Steve and I had seen a bunch of Russ Meyer movies, from The Immortal Mr. Teas to Supervixens and, of course, Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!. There was a repertory theater that had a Russ Meyer night, and the main feature was Faster, Pussycat! with Mudhoney first. I thought, “I’m kinda hungry,” left the theater to get a bite, came back and, of course, missed Mudhoney. But that name stuck with me. It was the perfect name for a band that I would want to be in.

Bernstein: Dan and Mark would sometimes come to movie night at my apartment in the mid-’80s. On occasion, we rented Russ Meyer movies, which were hard to find. I seem to remember that when they named the band Mudhoney, they hadn’t actually seen the movie, so we rented it one night. I was pushing for them to name the band Common Law Cabin, after another Russ Meyer movie, but that’s why I shouldn’t name bands.

“I feel bad and I’ve felt worse/I’m a creep, yeah, I’m a jerk.” —“Touch Me I’m Sick”

Turner: The word “grunge” was definitely a touchstone for the scene at the beginning, since a lot of bands just wanted to get down and dirty. It wasn’t really punk rock, even though it was played by punk rockers. I think the best term for it is “post hardcore.” Bands like Killdozer, Naked Raygun, Big Black—people who had been in the hardcore scene but needed to do something different.

Arm: In Seattle, audiences responded to bands they really liked. People were slow-motion rolling over each other with big grins on their faces. The (psychedelic drug) MDA might’ve had something to do with it.

Turner: [Sub Pop] really wanted to think big, which is rare for a small indie label. The slogan “World Domination Now” was tongue-in-cheek, but it was also something they felt should happen.

Jay Hinman: In 1988, Sub Pop had their publicity machine cranked up. When a new single would come out, it’d be like, “This is the greatest thing since God!”

Pavitt: If Mudhoney had sucked, Sub Pop would have gone out of business.

Turner: Bruce suggested we go to a real studio since Mark had been bringing him shitty-sounding cassettes. Bruce suggested we go to Reciprocal Studios with Jack Endino and do some recording.

Pavitt: At the time, we did give bands advances, but they were incredibly modest. We paid the studio $50, and Mudhoney recorded “Touch Me I’m Sick.”

Turner: “Touch Me I’m Sick” is certainly not an original riff or anything. There are other bands that have similar riffs: the Stooges, the Yardbirds. That was always my favorite stuff, that real gnarly ’60s garage.

Pavitt: “Touch Me I’m Sick” was the rare time we released an original version (of 800 copies), then we did a second edition with different packaging. People would call and say, “We want more copies,” and we’d say, “OK, if you want more copies, you’re going to have to send some money up front to make sure you get our next limited-edition single.”

Thurston Moore: “Touch Me I’m Sick” was in a plastic sleeve: no pictures, just a plastic holder with brown vinyl, totally fucking ugly! But there was this window display at (Hoboken, N.J., record store) Pier Platters. The entire front window had all these brown vinyl seven-inches covering it, and it said in big letters, “MUDHONEY HAS ARRIVED!” It was ridiculous. I mean, who the hell had even heard of Mudhoney at that point?

Jonathan Poneman: Mudhoney’s early stuff was very simple, very concise, with an emphasis on momentum and explosion. The way they employed a fuzz pedal went beyond anything Blue Cheer had ever done. There was also an unpredictability, which may be due to them being a young band that was just finding its footing.

Turner: Our first gig was April 19 (1988), with Das Damen and Blood Circus, after we recorded “Touch Me I’m Sick.”

Pavitt: Jon and I saw Nirvana’s first show in Seattle, right around the same time, and there were three people in the audience: me, Jon and the bartender. They were fairly mediocre. We thought, “OK, maybe we can do a single by these guys.” But when we saw Mudhoney for the first time, we looked at each other and knew we had a real record label, because we’d have at least one incredible band.

Stone Gossard: I was glad Steve and Mark had found each other again and were making music that was more natural for them. It was different than wherever I or Jeff were going. I remember thinking I should have paid closer attention to what they wanted to do in Green River.

Jeff Ament: I saw them at (Seattle venue) Motor Sports Garage when it was blowing up. Part of me was jealous.

Steve Manning: The first time I saw them, I knew I’d never miss a show by this band again. I’ve probably seen as many Mudhoney shows as anybody, besides the members of the band. I didn’t know them; I idolized them. Sub Pop reissued Superfuzz Bigmuff plus singles a few years ago, and there’s a picture of Steve Turner lying onstage with his guitar and somebody spooning him. That’s me.

Ed Fotheringham: They were exciting. They were funny. Matt Lukin always slapped his ass. This was a big thing to him, slapping his own ass. There was an irreverence to them that was palpable and appreciated.

Peterson: As a photographer, you couldn’t really ask for much more: the long hair, the ripped jeans, the pseudo-sarcastic thrift store T-shirts, just that unbridled energy. Matt didn’t really care what he was hitting; he was more interested in swinging his bass over his head than playing the right notes, and it worked part of the time. You don’t go to a Mudhoney show to have them replicate the album note by note. It’s about what kind of car crash is going to happen. Capturing that car crash at that moment was what was great about photographing Mudhoney.

Arm: The Boxing Club gig (on July 8, 1988) was crazy. I don’t know who rented the space, but we get there and find this door to the basement with all this S&M bondage gear: crosses with straps, all these cabinets with handles for dripping wax on people, crazy shit.

Peterson: It was dumb, but it wasn’t stupid, you know? It was off the rails but without being too contrived. Even just the use of the Super-Fuzz and Big-Muff, which are both somewhat corny guitar effects. And singing about dogs and sickness and sweet young things. They really captured the spirit of teenage rebellion. I just think it’s their personalities. Mark is really smart and has a super-dry sense of humor. Steve is totally goofy. Danny’s this super-sweet guy who lives to drum. Matt was played up as the guy from the woods. But Mark and Steve secretly have these huge, huge, huge record collections that they drew inspiration from.

“Pull down your pants if you like us.” —Mark Arm, Berlin, Oct. 10, 1988

Peters: I’m not sure if it all happened at the same session, but we had a bunch of songs—“Touch Me I’m Sick,” “24” and “You Got It”—and gave them to the Sub Pop guys. The next thing you know, we’re in the studio recording an EP.

Arm: I remember Steve coming over to my apartment, playing our electric guitars acoustically, without any amps. We didn’t have any. A song called “By Her Own Hand” was a definite first song. I remember calling “No One Has” “The Wipers Song,” because that’s what it sounded like. One was called “The Human Cannonball Song,” after (Butthole Surfers song) “Human Cannonball.” “In ‘N’ Out Of Grace” was “The Blue Cheer Song.”

Bernstein: The line in “Mudride” that goes, “I’ve got a belly full of ouzo, a head full of hurt,” is when a bunch of us drank ouzo at our friend Julianne’s house, before going to see Girl Trouble at this bar near the University of Washington, then ended up at this college party where Mark threw his head back through a window.

Bettina Richards: For me, the triggers (of Superfuzz Bigmuff) were the huge, fat guitar sounds and Dan’s unbelievably propulsive drumming. It just really connected, in part because when a lot of people were looking to strict punk icons, they were harkening to garage rock, to ’70s rock like Creedence and Blue Cheer. These were records that I heard on classic-rock radio, but I probably would have dismissed them as not as cool. Then suddenly it was like, “Oh, this shit is really cool.”

Pavitt: As someone who used to read the NME indie charts, which were usually exclusively British releases, I remember when Dead Kennedys got on there and thought, “Oh my god, there’s an American release on the indie charts.” Superfuzz Bigmuff ended up going to the top of the NME indie charts and stayed there. It was pretty unheard of.

Ament: At the time, I couldn’t appreciate [Superfuzz Bigmuff], because there was a competition going on. There were some things said from Mudhoney’s perspective about us that were hurtful and totally not truthful. I couldn’t help but stand on the other side of the line that was drawn and say, “We’re better.” [Laughs] When Green River broke up, [Arm and Turner] stayed in the Sub Pop camp, and we kind of weren’t allowed in the Sub Pop camp. So we went and found our own deal. It worked out for everybody.

Pavitt: In July of ’88, Jon and I went to the New Music Seminar (conference in New York) with very little funding. We met the gentleman that was organizing the Berlin Independence Days festival. [The German promoter] flew the band, Jon and myself out to this festival. It was an amazing bit of luck, and Mudhoney pretty much blew everyone away. From that show, they were able to land a two-month European tour.

Turner: The Berlin festival was one of those weird things that was funded by the government. We played a good-sized venue there, and it was a lot of fun. We drank a lot, and I think all six of us (Mudhoney, plus Pavitt and Poneman) were in one hotel room. It was a real decadent city.

Arm: We never, ever adjusted to the time in Berlin. We slept all day, woke up at 6 p.m., then stayed up all night. We discovered hefeweizen beer on that trip. We’d been drinking nothing except Schmidt’s or Olympia beer. I look over and Bruce has this giant glass of beer nearly a foot-and-a-half high, and all of us were like, “What’s that? Wheat beer?”

“Happy New Year, losers. All you’re going to do is have your shitty old jobs back tomorrow.” —Mark Arm, Seattle, Dec. 31, 1988

Turner: Almost immediately after Berlin, we went on tour with Sonic Youth. We brought Bob (Whitaker, who would later be Mudhoney’s manager) along with us to entertain us. He was just some party guy we knew. We figured he could get us places to stay. He was a lot more outgoing than us.

Hinman: Early on, Bob was definitely the ringleader, egging them on to drink more and to new lows.

Moore: Bob was there for one reason: to have a lot of fun. We’d make fun of our differences: We were a dour, Velvet Underground-listening, black-wearing, book-reading kind of band in the van, whereas Mudhoney were torn shirts and jeans, going out and getting completely drunk, then rolling around in the parking lot, and buying records all the time. So we used to talk about their van as this pot-smoking, beer-drinking, cassette-tape-listening party machine, and our van as sort of like this mood-lighting-and-reading-Charles-Dickens experience.

Turner: For the longest time, the only thing we had on the rider was beer and peanuts. Club owners would be like, “Well, don’t you want sandwiches or something?”

Richards: Dan always blew my mind in the amount of beer and liquor he could consume and still play drums like a mother. A ton of bands that followed completely imitated the kind of accelerated drum roll that he did. He really built the foundation for this fever pitch that drove people to jump off the stage.

Arm: The first tour we did, just after Superfuzz came out, we played Lexington, Ky.—and even went on the local college radio station before the show to yak—and no one showed up. We made $14, a six-pack of soda and two packs of cigarettes. They were like, “Sorry man, it’s all we’ve got.”

Pavitt: They all had a great sense of humor, and that’s one of the reasons they were so popular. Mark Arm was hilarious onstage. Matt Lukin was so unusual, like Andy Kaufman but more of a backwoods, redneck conceptual artist. Sonic Youth were completely enamored with Matt Lukin. They were these sophisticated people from New York, and they meet Lukin, who was from Aberdeen, a creative genius, but kind of crazy.

Richards: Matt was kind of in his own zone in every way: wearing really tight, straight-leg jeans and big, bold striped shirts; seemingly oblivious to everyone around him and making random comments into the mic. Steve wasn’t bothered by all the people jumping on the stage, but I don’t remember him jumping off the stage like Mark. What always amazed me was the number of dudes getting up and flailing around onstage, then jumping off real quick. They fed the fire, for sure. I hadn’t really been to a show where I’d seen lemurs like this running up there and jumping off amps, wanting to be onstage for 30 seconds.

Arm: MTV totally wrecked it, though. Our first tour, you’d go around the country, and each town had its own weird way of reacting to the bands. Then a couple of years later, it was like MTV showed people how they were “supposed” to behave, and that’s what everyone did from that point onward. Or just the stupid Lollapalooza giant-mosh-pit thing. Lame.

Pavitt: In late ’88, Nirvana’s “Love Buzz” single came out, and they opened for Mudhoney on some West Coast dates. I remember Steve Turner coming back and saying, “Kurt Cobain played the guitar while standing on his head,” a complete impossibility, and Charles Peterson ended up having a photo. If I hadn’t seen the photo, I wouldn’t have believed it.

Arm: New Year’s Eve at the Central Tavern was a very, very, very—as you might imagine—drunken show. After that show, Dan told me, “You should talk less between songs.”

“We came all the way from America just to fuck up.” —Mark Arm, London, March 24, 1989

Turner: Back then, if Sonic Youth said that you were cool, everyone thought that you were cool.

Pavitt: Sonic Youth and Mudhoney wanted to do a split single together, they wanted to tour together. Sonic Youth was pretty much the band of the moment in terms of the British press. That really helped popularize Mudhoney and Sub Pop, so there was a series of lucky breaks. Within nine months, Mudhoney went from the cassette demo to big in England. It was unusual.

Arm: The U.K. was crazy, and Sonic Youth, at that point, were like total walking gods. The previous tour, they had Dinosaur Jr with them, which made that band in the U.K. They could bring someone over and basically anoint them, so we were really lucky they decided to bring us. (Famed BBC disc jockey) John Peel was playing “Touch Me I’m Sick,” so people weren’t totally unfamiliar with us.

Moore: Mark used to try to mythologize Sonic Youth’s profile. I remember him being in my hotel room on tour and calling up different bands staying in the same hotel at three in morning, saying he was me, asking people to come up and hang out. They’d be asleep, not very into it, and he’d be yelling into the phone, “Don’t you know who I am? I’m Thurston Fucking Moore from Sonic Fucking Youth, and I demand that you come up here and hang out with me!” And then hang up the phone. I’d be like, “Mark, please don’t do that!”

Peterson: It’s always the case that if a band breaks somewhere else, people in your own backyard will sit up and take notice. Sub Pop played it pretty smart. Mudhoney going over and doing that first English tour, which was such a riot, really added to that mythic quality they had at home.

Arm: The very first show in Newcastle is where I learned that British audiences don’t have a sense of irony and sarcasm. Before we left the stage, I made a few comments like, “Sonic Youth’s from New York. In the old days, if you wanted to show appreciation, you’d spit on the band. We’re not into that thing, we’re from Seattle.” Evidently, Sonic Youth got spat on—tons—and (guitarist) Lee Ranaldo was fucking furious. It was something I never thought anyone would do because of something stupid I said.

Moore: Our music wasn’t as consistently rock ’n’ roll as Mudhoney’s; we were definitely playing some weirder, slower stuff. But the audience didn’t care. It could have been Peter, Paul And Mary for all they cared. They were gonna slam dance the entire length of the set. And stage dive and do what punk rockers do—or what they thought punk rockers did, anyway, which was to really get in your face, spit, slam into you while you’re playing. I remember that being a bit of a consternation for Lee.

Arm: Stage diving had never occurred [in the U.K.] before. We were used to it from punk shows from the early ’80s. We played a show in Nottingham, and there was a security moat between the stage and the audience. And a platform, with a little queue forming, mostly young boys who wanted to climb up onto this platform, then politely dive off into the crowd. That was insanely funny. It wasn’t always the case, but it was like, “Please, sir, can I take a turn at this stage-diving thing? I would like to give this a go!”

Moore: At a lot of gigs, we’d just be getting started on our first song and Mark would come flying across the stage and do a backflip into the audience to get the riot started. It was totally awesome.

Peters: We were in Europe for nine weeks. We had two days off in those nine weeks, and they were used for driving. The best thing about it was we all went insane at the same time.

Arm: A later show we played (with Nirvana) at a school in London was called a “riot” by the British music press. My smartass mouth got us into trouble again. The crowd was surging forward, and our stage was kind of a makeshift thing. The kids were getting up on it, trying to jump off, which was, of course, getting in the way of us doing our thing. So I was like, “Hey, let’s get everyone up on the stage,” thinking they’d realize that 400 people wouldn’t all fit up on this tiny little stage. Well, they all charged up onstage, we got pressed up against the back wall, security had to move everyone back, and we had to patch everything up and get hooked into the PA again. This was all because some kid got up onstage and unplugged one of my boxes. So everything calmed down, the song ended, then I was like, “Hey, let’s everyone get on top of the PA!” And they went, “Of course!” Making my ridiculous statement even more ridiculous. So the kids surged forward again, and my friend Keith told me that he had to physically restrain one of the security guards from beating the shit out of me.

Peters: I think that show is more legendary now. People talk a lot about it because it was Nirvana’s first show in London, and hindsight has changed the show into something it actually wasn’t. I remember it being a great show for us. We were kind of “the band” there at the time. Nirvana opened up, and TAD played as well. Nirvana broke strings left and right, they were barely able to finish their songs, they were just having all kinds of technical difficulties. They did smash up all their gear at the end. The next day, the papers reviewed it and said Nirvana was no good. The people who reviewed the show back then are now saying it was the best thing ever.

“What do you fuckin’ want? You want me to bare-ass it, dontcha?” —Tad Doyle, Seattle, June 6, 1989

Arm: Our Seattle shows were at small clubs, but when we got back from the European tour, Sub Pop decided they wanted to do something called Lamefest with us, TAD and Nirvana at the Moore Theater (on June 6, 1989). We were like, “You’re crazy.” The only punk bands we’d ever seen play there were Dead Kennedys; that was as big as it got. I couldn’t imagine where this audience would come from, and yet it sold out, and this is long before anybody knew who TAD or Nirvana were. It was around 1,200 or 1,500 capacity, a huge jump from 200.

Poneman: It was seen as a daring act to rent out the Moore Theater for three of our bands that previously had just played bars and house parties. The show sold out, and everyone involved was really stunned that the show did as well as it did.

Pavitt: Lamefest was the definitive turning point in the Seattle music scene.

Arm: I just couldn’t figure out where all those people had suddenly come from. I guess it’s really exciting that people turned up and were starting to get into it, but it felt kind of odd to us. I’m not precious about having a small scene or not letting outsiders in, but we were like, “What were your interests before this?”

Pavitt: The manager of the Moore told some of his security staff to go home. He said, “A local show has never sold out the Moore, so I don’t anticipate many people showing up.” It was complete mayhem.

Arm: Security was just fucked at that show. It was these guys we kind of knew, a group of guys called the Fallen Angels, who modeled themselves after the Guardian Angels, wore berets and military garb and were always doing security at local shows. They got hired again for this show and were just beating the shit out of kids.

Manning: Things changed quickly. Lamefest wasn’t that far off from Mudhoney’s first show. It didn’t feel like things had blown up yet. It was like the coming together of a bigger community and almost a celebration of Sub Pop as an entity.

Pavitt: The sound engineer for Sonic Youth was doing sound, and he looked at me and said, “You know, you’ve got something going on here. This is really phenomenal.” He’d been traveling the world with Sonic Youth, which was the biggest indie band in America at the time, and he said, “I don’t know what you guys are doing, but this town’s about to blow up.”

Gossard: Steve Turner was saying, “We might be doing good with Mudhoney, but check out Nirvana. These guys have got real hits!”

Poneman: A lot of times, when people are writing about the evolution of Seattle music, they mention how Nirvana put the pop back into the music that was being made in Seattle. But I would argue that Mudhoney did that much more obliquely and was every bit as successful as Nirvana.

Jennie Boddy: Mudhoney was the biggest seller on Sub Pop. We were always getting our phones turned off. I remember Bruce walking around wondering, “When is Mudhoney putting out another record?” Mudhoney would always save the day. There would be no Nirvana releases or anything else without Mudhoney putting stuff out. They were the saviors of the electric bill.

Interviews by David Bevan, Jonathan Cohen, Corey duBrowa, Andrew Earles, Jason Ferguson, Matthew Fritch, Tim Hinely, Pat Hipp, Bruce Miller and Noah Bonaparte Pais