Kinks leader Ray Davies has been banned from America, bored of the 20th century and, at times, bigger than the Beatles. Davies may not be like anybody else—his songbook is one of rock’s greatest treasures—but he’s finally figuring out who he is.

Interview by Yo La Tengo’s Ira Kaplan

Photo by Christian Lantry

At one point during MAGNET’s interview with Ray Davies, the great songwriter stopped mid-sentence to peer out the window of the Dream Hotel overlooking 55th Street in Manhattan at dusk. Something had caught his eye.

“Isn’t that light out there like Edward Hopper lighting? Is that Edward Hopper time or not?”

Observing light, life and human nature with superhuman focus is Davies’ stock-in-trade. His best songs feel photorealistic and sound suspended in time. They are sometimes nostalgic and beautiful, and other times they are cynical and brutal. Davies himself is just as contradictory: combative and sensitive, a shy, self-examining middle-class hero from north London who’s had no problem indulging in rock ’n’ roll excess and showmanship. He’s often called a creative genius and a control freak, which are both compatible and necessary traits for the life he’s led.

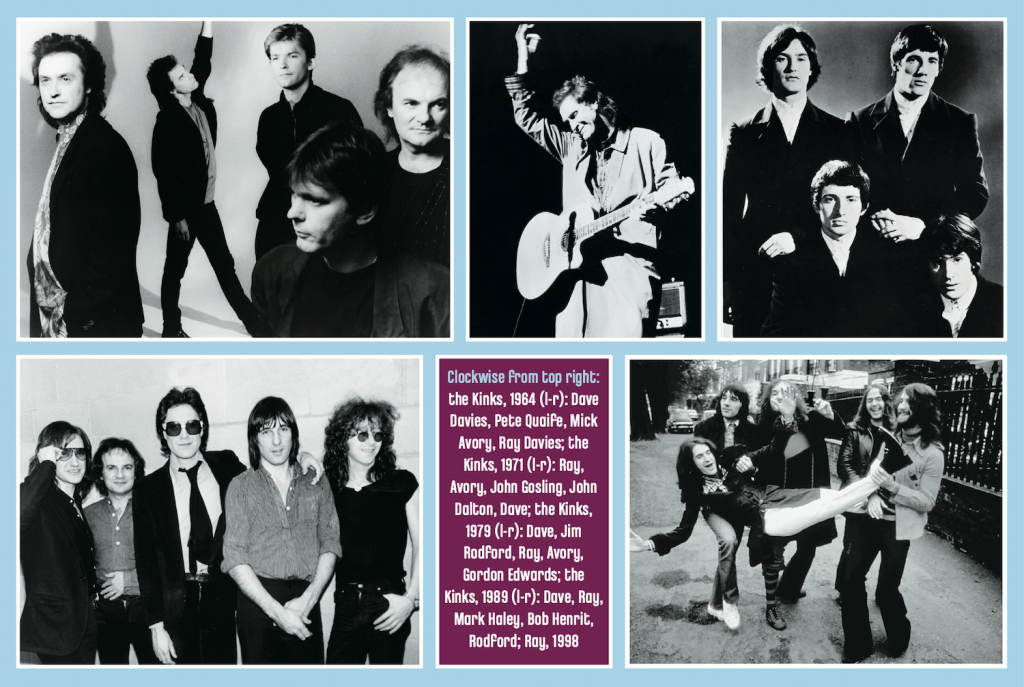

The Kinks started in 1963 and soon became mop-topped soldiers of the British Invasion but, as it turned out, they fought too well: The sight of Ray and younger brother/guitarist Dave trading punches onstage didn’t compare favorably to the public profile of the affable Beatles. In 1965, the Kinks set out to conquer America with “You Really Got Me,” a revolutionary hit single that broke the sound barrier by introducing amplified distortion to a guitar riff, earning a reputation as the first heavy-metal song. While touring to promote “You Really Got Me,” however, a punch-up between Davies and a union official on the set of the TV show Where The Action Is resulted in the group’s banishment from U.S. stages. The Kinks—Ray and Dave, plus equally combative drummer Mick Avory and bassist Pete Quaife—wouldn’t be allowed to perform in America until 1969, effectively sidelined for much of the most important decade in rock ’n’ roll history.

Davies continued to battle from his British island, and his songwriting in the latter half of the ’60s became deeply emotional (1967’s “Waterloo Sunset”), satirical (1968 pastoral-pop masterpiece The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society) and ambitious (1969 song cycle Arthur (Or The Decline And Fall Of The British Empire)). These artistic triumphs didn’t always translate to commercial success—especially in the U.S., where the Kinks’ English quirks were not well understood—and the band’s troubles were compounded by bad timing. Village Green was released the same day as the Beatles’ White Album and was virtually ignored by critics and the listening public. Written for a TV musical and poised to become the first rock opera, Arthur was delayed and ended up getting tagged as a pale imitation of the Who’s Tommy, which was released five months earlier.

Given the increasingly personal tenor of his songs, it’s no surprise that Davies answered with 1970’s Lola Versus Powerman And The Moneygoround, an album whose songs take bitter jabs at the record industry but is leavened somewhat by classic gender-bending love song “Lola.” Alt-country antecedent Muswell Hillbillies, its title a nod to the Davies’ childhood home in London’s Muswell Hill, followed a year later, but 1972’s Everybody’s In Show-Biz began a string of less-than-stellar concept albums and sprawling rock operas. The Kinks barely survived the ’70s (an onstage overdose of barbiturates nearly killed Davies in 1973), and turmoil reigned as Ray and Dave continued to feud.

By the late ‘70s, the Kinks were playing arena rock and courting American audiences again. They scored an early MTV hit with the Caribbean-flavored “Come Dancing” from 1983’s State Of Confusion. Just as the Kinks had become resurgent, however, Davies turned his attention to making a music-video-style film, 1985’s Return To Waterloo, and drummer Avory was fired after yet another fight with Dave. (Quaife, the Kinks’ peacemaking bassist, had left the group in 1969.) In 1993, with only Ray and Dave left standing, the Kinks quietly issued Phobia, their final album.

While the Kinks lay dormant, American listeners slowly rediscovered the band’s catalog—particularly the jangly, idyllic tones of late-’60s albums such as Village Green—and developed a cult-like reverence for Davies’ songwriting. Within the confines of indie rock, the Kinks’ forever-underdog status and Davies’ malcontent worldview resonated perfectly. In 2000, Davies returned to the stage with Hoboken, N.J., trio Yo La Tengo as his backing band, performing Kinks songs and working out new solo material at the Jane Street Theater in New York. He subsequently took YLT on the road with him.

Four years later, Davies was living in New Orleans and writing songs for his first solo album. While walking in the French Quarter with his girlfriend, he was shot in the leg as he tried in vain to apprehend a purse snatcher.

“Wrong place at the wrong time,” Davies tells MAGNET of his attempted act of heroism. “Tried to defend a lady’s honor. I didn’t like the way he was shouting and shooting his gun at the ground. I’d had a bad day, and he was the last thing I needed.”

The scariest moment of the entire ordeal occurred in the trauma ward of Charity Hospital. “They were worried about me because I’ve got a really slow heartbeat,” says Davies. “I went down to about 24 beats per minute, and I was really frightened because I could see they were frightened.”

Davies rebounded to kickstart his solo career, which has so far produced 2006’s Other People’s Lives and the recent Working Man’s Café (New West/Ammal), the latter of which came as a result of Davies recording in Nashville with co-producer Ray Kennedy (Lucinda Williams, Steve Earle) and an all-American band of studio musicians. Just as the Kinks wryly observed English life, Working Man’s Café finds Davies surveying his American surroundings (the New Orleans-inspired “The Voodoo Walk”) and talking globalization politics (“Vietnam Cowboys”) while taking stock of his own legacy (“Imaginary Man”). No matter where he is in life—in England or America, celebrated or unjustly overlooked, with the Kinks or on his own—Davies has never stopped looking around.

MAGNET enlisted Yo La Tengo singer/guitarist (and former music critic) Ira Kaplan, a man who both knows his way around a Kinks tune and a journalist’s tape recorder, to interview Davies. The two began with a discussion of how the landscape of Manhattan has changed since Davies, who turns 64 on June 21, last visited.

Kaplan: I’m never comfortable being asked—and won’t ask you—about what you make of America and the changes.

Davies: Artists that came out during the mid-’60s, it was a time of change, it was a time of revolution. We weren’t really trying to change the world, but the times dictated that we would seem to be. And the world was changing. I don’t think the world would’ve been any different had the Beatles not evolved. I think they happened to be the signature on the document that said the world changed. I think it would’ve changed anyway. How do you feel about that?

I don’t know. I’m more the kind of person who thinks every little thing somehow adds up in ways you can’t quantify.

I was watching A Hard Day’s Night on the Independent Film Channel. I’d never seen the film. When that came out, I was really busy learning how to write songs and trying to keep apace of my own life. But it’s pretty incredible when you look back. There was almost a religious moment at the end of A Hard Day’s Night, when the Beatles are singing and the audience is screaming. I went through that with our shows. We didn’t hear ourselves play for two years … A Hard Day’s Night was so charming, the way it was portrayed, so innocent. It was a really simple story about four blokes getting on with their lives, finding this method of communicating that touched a nerve in society. To add to what I said, society was ready to be touched by them and the music explosion.

Did you write songs before the Kinks?

My whole songwriting journey started with insomnia. My sisters used to take turns walking me around when I was a baby, trying to get me to sleep. The only way they could get me to sleep was to play gramophone records. All night, as long as it took. It was a wind-up record player. When it wouldn’t work, one of my sisters just moved it around with her fingers, like a rap DJ. I feel like I came into songwriting because I couldn’t sleep. Because I wanted to be something else other than a songwriter. I wanted to be an “artist,” in a kind of innocent way. But [songwriting] was something I could do at one or two in the morning. There wasn’t all-night television (back then). There was nowhere to go. I wrote “Tired Of Waiting For You” and the chords to “You Really Got Me” when I lived with my sister.

Before there was a band to play them?

Yeah. I did it as a pastime; I never thought about writing songs properly until our second single. We did a Little Richard cover as our first song (“Long Tall Sally”), but it was enough to get us started. It wasn’t until “You Really Got Me,” our third single, was a big hit that they actually said, “We want you to write another one.” By then, I didn’t want to write songs anymore. I just wanted to be normal. But I said, “All right, I’ll come up with another one.” The next song I wrote, while my publisher was waiting in the next room, was “All Day And All Of The Night.”

That’s one of the things I’m curious about: the incredible pace of the old work. You’d have a recording session booked at two o’clock so you’d write the song at one o’clock.

It wasn’t a matter of hours. We had a matter of days to get it together. I remember we were going up north to play a gig, and I went to see my publisher because the royalties hadn’t started coming through. “You Really Got Me” was the first success, and you had to wait a year for the royalties to come. By then I was already foolishly thinking of getting married and trying to get my own home. I lived in a little apartment that was $15 a week, what they call a bedsit. So they wanted me to write another single because “You Really Got Me” was going up the charts. I wrote [“All Day And All Of The Night”] the following day, rehearsed it at a gig in Birmingham, came back overnight and recorded it. It was all very fast. But still, it wasn’t the notion of being a songwriter. I was fulfilling a role.

When do you think that changed?

When journalists and media people put their tag on you: the guy who writes hit songs. It took years for me to realize that other people had insight or thought into the psychology and emotions of the songs in the same way I felt them when I wrote them. Maybe it’s something to do with my nature, but I don’t give away emotions easily. When people said they liked “Waterloo Sunset” or they had a fondness for songs like “This Strange Effect,” which was written for someone else (British teen idol Dave Berry), it suddenly occurred to me that other people had these emotions, too. What a great communicating vehicle it is. It’s like a secret message going through the radio to some listener somewhere: I feel the same way as you do. That was a real revelation.

Weren’t you reacting that way to the songs that you heard when you were young?

No, I don’t think so. In the house where we grew up, my older sisters would just dance and move to the music: bebop and ballads. I was interested in song structure, but putting the emotion into the song hadn’t occurred to me until I got feedback from people who’d heard it.

What about, say, (1965’s) The Kink Kontroversy, which sounds different than the earlier records. Did you feel like a songwriter then?

That had to be done very quickly.

There’s a real mood to that record. Is that accidental from writing it so fast?

I think it is, and through a bit of life experience. I remember how “Till The End Of The Day” came about. I had a bit of writer’s block, and my managers were getting worried because I hadn’t produced anything in almost a month. [Laughs] They sent Mort Shuman ’round to my house, one of my hit-writing heroes. He wrote “Save The Last Dance For Me” with Doc Pomus. This mad, druggy New Yorker came ’round to my little semi-detached house in London. He said, “I’m here to find out what you’re thinking about. I’m not interested in what you have written; I’m interested in what you’re gonna write.” He was completely paid off by my managers to say it. I thought it was ridiculous that there was so much importance put on it. If I don’t want to write for a month, I won’t. To say the least, I was pressured into doing it. Then I went off to stay with my sister and bought a new toy, a little upright piano, and wrote “Till The End Of The Day.” That song was about freedom, in the sense that someone’s been a slave or locked up in prison. It’s a song about escaping something. I didn’t know it was about my state of mind.

That’s the last Kinks song written in the “You Really Got Me” style. Was there pressure to write “You Really Got Me” version seven?

I think it’s good to repeat the style if you take it somewhere else. It’s an interesting choice, that album (The Kink Kontroversy), because we’d had all our bust-ups in America. It was a wonderful time to experiment. Of course, in parallel, the Beatles were doing their experiments with George Martin, reversing tapes. In those days, you didn’t have ProTools or plug-ins or any of that. Lots of big sounds were put together in the most basic way, like the music workshop rather than the modern scientific method.

With “Dedicated Follower Of Fashion,” were you just being ornery? Like, “We’re not gonna give them ‘All Day And All Of The Night’ again.”

There’s a lot of venom in that song. You don’t have to be in Metallica to write venom. It’s as venomous as satanic heavy metal, but it’s done with humor.

Did the Kinks rehearse at the time, or did you just go into the studio and play?

We’d play at soundchecks. I’d try an idea for a new song at a soundcheck jam. “All Day And All Of The Night” was in the back of a car, in a classic Buddy Holly mode. It’s the way a film director would want to shoot it. It had to be done that way. The only way I could teach them the songs was in the car on the way to a gig.

Do you have a vivid memory of a song that sounded completely different when the Kinks played it than when you imagined it? I mean, you said “Till The End Of The Day” was written on piano, but you must’ve had some idea of what the Kinks would sound like playing it.

A lot of the time, I write records. In those days, particularly, I had the idea of what the record sounds like. I suppose (it’s like) the way Phil Spector does, as well. We had a producer, Shel Talmy. Shel was more like a soccer coach. He would stop us from doing [a take] too many times because he was aware we had to pay our own studio costs. It had to be cheaply done.

The Beach Boys notoriously rebelled against what Brian Wilson was hearing and didn’t want to play what he wanted them to. Did that happen with the Kinks?

Yeah, after a while. With my brother, particularly. But in the end, he’s a smart kid and always knew when it was a good idea and always got on with it but protested bitterly. I just went through a really sharp phase in my life where my brain was working spot-on and just knew what I had to do. I knew what (1966’s) “Sunny Afternoon” looked like before I wrote the song. It was written on that same piano. It was a flat top; the notes were quite mellow. It was more like a celeste than a piano.

So even by the time of “Sunny Afternoon,” that’s a song that you bring into the studio and it’s just played a couple times.

Yeah. I was so clear about what I wanted in my own head. Mick the drummer and Pete the bass player—not so much Dave—went along with it because they trusted I knew what I was doing. That, to me, is the important part of collaboration: to surrender your own wishes sometimes because you know there’s a vision. It takes really smart, talented, sensitive players to go along with that. And they were, those guys.

People like me think back about that time, when bands were making three records per year. The output just seems so …

It was four singles, an album, possibly an EP (per year). It’s all those weird record deals in those days. For the most part, they did come quickly because I was so rushed around doing things. If it took more than half an hour, I had to do something else. When you write, do you go into a room with a tape recorder and play until you get inspired?

No, we couldn’t be more different. Mostly, our band writes together. We just jam and see what happens. If I do something separate, I’m never together enough to record it. I try to write it down in some pidgin notation so I can remember it the next time I play it.

It’s different. I’ve even got an old manuscript with “You Really Got Me” on it. I wrote that at my parents’ house, and we didn’t have a tape recorder.

Why wasn’t “You Really Got Me” your first single?

Well, it existed in musical form, with the instrumental part written two years before we recorded it. But we were doing all these covers. I didn’t even want to sing in the band; Dave was the best-looking, so he sang. And we had a road manager called Jonah, who was a neighbor. Jonah looked really cute; we let him play maracas and sing. (At shows) I just stood on the side and did the occasional vocal. We did “Long Tall Sally”; I sang that. It wasn’t until we opened for the Beatles that we ended with “You Really Got Me.” That was the only song that got a reaction. People’s heads turned; they stopped screaming for the Beatles.

Do you think the lack of precedence for that song stopped you guys from doing it at first? At first, you’re doing what other people are doing, then you’ve got this thing that no one’s done before.

Certainly not in the way we did it. It’s an old story, but the bass speakers were blown on our gramophone, so all the records sounded fuzzy. Dave stuck needles in [his amplifier] speaker, with no knowledge that somewhere in this country, Link Wray was doing a similar thing. It made us sound so different. People were drawn by the sound rather than what the song was doing … The record company turned the demo down, said it had no chorus.

Was it a demo that sounded similar to …

Like all demos, it’s lo-fi and foggy-sounding. But it’s not until they came to see us play it live that they got it. The day we recorded it with Shel at Pye Studios, in a posh studio, it sounded awful. They wouldn’t listen to us. I said, “It’s not the way I hear it.” It’s the same old sort of upstart thing. My publisher said, “There is a way you can stop it. Don’t grant a publishing license.” In the end, they relented, and we went in and made it the way we wanted to do it. The scariest part was when I did the vocal; the backing track sounded exactly how I wanted it, but I’d forgotten how I wanted the vocal to sound. Just before we start taking it, the tape ran, and I heard the first riff and drums come in. I thought, “I’m not going to sing it big. I’m going to sing it small.” When I was an art student, I did a bit of drama at school, and there was kind of a secret radical guy who taught me how sometimes, when you step back in the photograph, you get noticed more. Or when you speak quietly, people will listen. So I decided to play it small rather than go with that testosterone, which I’m not good at anyway. I went small, and it fit perfectly in the pocket for the rest of the song. Because I did a small vocal, it allowed the music to be bigger.

You brought up earlier the whole thing about the revolution of the ‘60s and the experimentation, but at the same time, the Kinks always feel a little cut off from that. You’re recording with your wife (Rasa, who occasionally did backing vocals) and your brother; there’s a real family aspect to it. To me, you’re always part of the time but separate from the time. Was that a decision or instinct or both?

It was the only way I could function, really. I still like to have a family unit. A band is a family, I guess. It was essential for me, because everything was so driven by my family. I used to play my first songs for my dad. I’m probably one of the only people of that time who actually wanted parental approval. I wanted them to like it. Normally, you’d say, “If parents like it, it’s uncool.” But I thought the fact my dad could sing “Sunny Afternoon” in the pub was absolutely fantastic. I’ve got this great book of folk songs, and they tell you how to play at the beginning. It says, “Play this intimately, as if among friends.” And that’s my little rule for songs. If you can get it past those people, you can get it past a lot of people. Because your family can be your strongest critics.

The notion of writing albums as albums seems like something you did with Village Green and Arthur.

I fought against having to write all the songs for the first album. I thought we had to have covers because it was part of our set. Then I got into albums; inevitably, there had to be a common unity between the songs. It’s called an album, it’s a collection of works. I think the Kinks were diverse with every single, which worked against us. Village Green was when we were banned from the United States, and there was probably no likelihood we’d ever get back to play here. So I moved to a place in the real northern suburbs, almost the country, and lost myself in being English, with no aspirations of ever coming back to America. I wanted to write something so entirely for me. I didn’t care if anybody liked it or not. It was a fabulous time but worrisome for my managers, obviously. In the end, it turned out to be a much-loved record, even though it wasn’t a gold album and didn’t win Grammys. But it sustains to this day. People listen to some of the songs, their jaws drop because it’s bold to do a thing like “Phenomenal Cat” and then “Animal Farm.” Even on that record, I wrote for the way something should sound. “The sky is wide” is a line in [“Animal Farm”]. I knew I could just about reach that note, and to me, the whole record is the way I sing that line. I knew that before it was recorded. I must’ve been so confident, so sure of myself. But there was a lot to worry about: We were banned from the most important market in the world and not getting a great deal of airplay in the rest of the world. And there we were, making this ridiculous record about wicked witches and a village green somewhere that didn’t really exist on the map.

You mentioned managers being resistant. Within the band, what was the reception to Village Green?

They probably thought I was not very well. Mick would always say, “Let him do what he’s doing, because nine times out of 10, it’ll work out in the end.” Dave enjoyed the experimentation, and Pete just went along with it.

You didn’t play the songs from Village Green in concert, right?

That’s one album we didn’t play live. We didn’t play “Sunny Afternoon” live until it went to number one. Maybe I was going through a difficult phase. People say the live act was fun to watch, but they were worried about us when they left the gig. There was a song, “You’re Looking Fine,” that Dave sang; it went on for 15 minutes—solos in the key of A, drum solos. When you think of the time it was made, 1968, I think the world was a bit like that: disorganized and on the edge and suicidal. But we got through that and got back to America in 1969.

What were you expecting to find when you got back to America?

Well, I’d heard about this festival called Woodstock, which, if we’d been allowed back, we obviously would have played. I heard about some of the new bands emerging: the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, the James Gang. When I walked onto the stage of the Fillmore East, which was our first gig when we came back, I’d never seen monitors onstage. We just had a PA before. So that was a culture shock for us. The whole atmosphere around a rock concert had changed because of (concert promoter) Bill Graham, who led that music revolution in this country. It had turned into something else; it was more political. A lot more guys coming to gigs, no screaming girls—or not so many, anyway. It became another counterculture, as opposed to pop.

The Kinks were a legendarily loose live act.

We didn’t need the Fillmore to make us loose. [Laughs]

Was everyone united in the looseness, or did you want it to be tighter?

I’d have liked it to have been a bit tighter, yeah. I was going through a guitar crisis at the time. I was playing a Telecaster, but I was uncomfortable with it. I’d have liked to do more acoustic songs.

I want to zoom forward.

Please.

There was a long period of time without a record by you. What happened to you, plus Dave’s stroke (in 2004)—those things must’ve been a catalyst.

What? Getting shot?

Or just the mortality.

Oh, mortality is just beginning to affect me. Not because of getting shot, but because of all the things on my mind not being dealt with prior to that. This new record is the songs I would’ve recorded if I had not had the accident.

Are the songs on Working Man’s Café new?

A lot of them were written while I was in New Orleans in recovery. “Morphine Song” is a song about self-survival, because I wrote that in the hospital. I got a notepad from the nurse, and then I didn’t change a line. “You’re Asking Me” was demoed in 1999, and it’s about someone continually asking me what it was like in the 1960s. Of course, I don’t have the answers.

When we were rehearsing with you for the shows at the Jane Street Theater (in 2000), quite a few of the songs changed from version to version. There’d be an extra verse or bridge. Were they finished?

Jane Street was a very interesting time. A lot of the songs were being written on the spot. I still think our Jane Street version of “Vietnam Cowboys” is one of the most successful versions of that track. Some of the guitar you did was very exploratory, like a scenic landscape, which is perfect for what I wanted … [Working Man’s Café] was like going back to the old way of making a record. I tried to work in that straight and contained, you’ve-got-three-hours-to-do-this frame of mind. The only thing I had to put up with was the culture surrounding me. I’ve never recorded with four Americans before. I was the only English person within miles.

Ray Kennedy is the co-producer, right?

He wanted to do my first (solo) record. [Working Man’s Café] had to be done quickly; I found out the record company (V2) was going out of business, which is a whole other nightmare that we won’t go into here. It wasn’t happening in London, so I got on a plane and flew to Nashville. It was a good test for me, coming from a family-unit band to the other extreme: players for hire, good players, nice guys.

How expressive are you to these musicians about what you want?

After all these years, it was interesting to find out whether I’ve got these talents (in the studio) or whether it’s an acquired way of doing things. With the Kinks, I went through a phase of being a bit too dictatorial. These (new) people didn’t grow up with me. So I had to be dictatorial in another way, like standing back and being louder. Because heaven knows I don’t want to get a bad reputation.

What’s the difference between being in the Kinks and making a solo record?

The Kinks I can see, I know what it looks like. It’s got boots on the letter K. Ray Davies, I don’t know what it looks like, don’t know who it is. I haven’t worked out the identity yet. In a band, if you do something bad, you’re only 25 percent responsible. [Laughs] If I do something I think is bad now, it’s all me. A lot of it is in the head. Maybe it’s always been Ray Davies making the records and I’ve been a coward, not wanting to accept responsibility. But like I said earlier, I don’t think I could’ve made any of those earlier records without the input of other people—or even the lack of input. Because it takes a great talent to know when to step back. I think the best musicians are the ones who’ve got humility. Same with the best actors. You can tell when a person is playing a few notes that they really mean it.

When selecting the songs for Working Man’s Café, did you choose the ones that held together thematically?

I went down to Nashville and had 35 songs. [Kennedy and I] mutually picked the songs. I surrendered a little bit. I was trying to be not the combative Ray, but the guy who says, “Yeah, that’s a good idea.” With the Kinks, we didn’t have demos to choose from, because we had to do something quickly. But boy, the changes in some of that music—“All Day And All Of The Night” next to “Dedicated Follower Of Fashion”—that’s why it was so hard for us when we came back to America. People hadn’t grown with us, so we had to do it by the hard slog. There was no MTV. Ironically, it was MTV that broke us completely here. But again, it killed us. I remember the phone call from (Arista president) Clive Davis. Clive said, “We’ve got real good news, and we’ve got a big problem. The good news is ‘Come Dancing’ is a breakout single. We’re putting it out because we can’t get it off [MTV]. The bad news is that you’re not a top-40 crossover anymore. You’re a pop band.” There’s a different dynamic to that. In a sense, gaining that chart success was a downfall.

You described writing Village Green, thinking that people weren’t listening.

You’ve got to do that. In the Arista days, we knew Clive was listening to it. He used to send records out to this testing place in Atlanta or somewhere, where people sat down with buttons going, “Hit. Miss. Hit.” So you knew someone would be listening to it. But “Come Dancing” is a song I wrote for my family. It’s a polka, really—a fast polka. It became one of our biggest singles in America, singing in a Cockney accent. Detachment in songwriting is good, though. Because if you’re writing in that inward, spiritual way, the right people will get it. Even though you think no one is listening, there is a voice there, and there is a receptive audience.

Special thanks to Doug Hinman, author of The Kinks: All Day And All Of The Night (Backbeat Books)

3 replies on “Ray Davies: Imaginary Man”

I have been a Kinks fan for as long as I remember, but Ray’s most recent solo album has a song (“one more time”) that brings a tear to my ey every time I hear it. It reminds me of days gone by when my father (still living) used to take walks with my younger brother (who was a down syndrome lad and avid Kinks fan). My brother passed away in 2001 from complications after elective surgery. My father is still a Kinks fan because of my brother.

Im also a long time kinks fan (Im 59)……Hey Steve, One more time brought tears to my eyes also – for no reason, just because its a wonderful song………sorry about your brother. I loved the Beatles, but he kinks songs talked to me and meant more to me as the years went by……so many wonderful songs that the general public is unaware of…….two sisters, starstruck, moments, dreams, to the bone, only a dream, scattered, big sky, hundreds more.

Could anybody be more ironic than Ray Davies? The MTV videos broke the Kinks into America as superstars … finally.

And finally that stardom broke what made the Kinks so good.

Most Kinks fans understand that what made the band great was their anti-trendiness and thoughful lyrics. They were at their best when they were at their lowest commerical success — singing songs about “Village Greens” and how “Everybody’s a Star.”