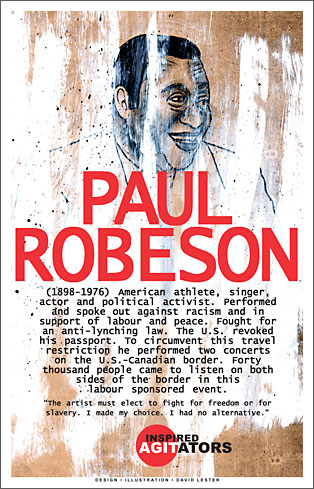

Every Saturday, we’ll be posting a new illustration by David Lester. The Mecca Normal guitarist is visually documenting people, places and events from his band’s 26-year run, with text by vocalist Jean Smith.

Every Saturday, we’ll be posting a new illustration by David Lester. The Mecca Normal guitarist is visually documenting people, places and events from his band’s 26-year run, with text by vocalist Jean Smith.

The night before my visit, my mother had a dream that I didn’t like the hot mustard she put on the turkey sandwiches she was going to make for lunch the next day. Unch-lay.

I arrived a bit later than I’d planned—closer to noon. I made tea, and then my father put a paint-splattered drawing board on a foot stool in the living room and set the tray of sandwiches on it. Three turkey sandwiches cut diagonally, one with the crust trimmed off. On a separate plate: kalamata olives and kosher dill pickles. Fuck, they were good. I liked the hot mustard very much, but didn’t say anything until my mother told me about her dream.

“That’s some kinda subtle dreamscape you’re operating there,” I said.

“Pardon dear?” She is going to buy a hearing aid soon.

We didn’t really stop eating until about 2:30, and then my mother started talking about dinner, about a BBQ chicken that my father and I were supposed to go and get at the store. I said something about not wanting to stay for dinner, and my father didn’t look too happy about not getting the BBQ chicken.

We continued to sit in the living room and I forget how we got onto the subject of New York, but I asked my father the name of the photographer he used to work with when he was an ad-agency art director. John Rawlings. Right. A name from my childhood. Rawlings this and Rawlings that. Rawlings. It’s a good name. This was in the ’60s, when evidently Vancouver didn’t have models. Seattle had models. Toronto had models, but it was my father’s big idea to go to New York to work with Vogue cover photographer John Rawlings. My father, also named John, stayed at the Lexington, the Berkshire and the Pickwick Hotel. (“It was down by the United Nations, and the rooms were so small I had to step out into the hall while your mother changed for dinner.”) Of course, I’d say “up near the U.N.,” because I’m most frequently downtown—SoHo, the East Village—but he was a Midtown man so the U.N. was “down.”

My mother wanting privacy is not the definitive barometer of the size of a hotel room, but I guess he was left with that impression. These are the sorts of things that can be thought about and savoured, rather than issues to correct or clarify. I was enjoying the idea of my father in the hotel hallway while my mother changed into something fabulous for dinner on the other side of the door—an aerial cartoon view—when my mother asked me where I stayed when I went to New York and I said, “The Holland Tunnel Motor Lodge on the New Jersey side of the tunnel. Right by the last set of stop lights before you go into the tunnel.” She didn’t look very impressed.

I don’t recall asking my father how he found the Berkshire, but he told me that he’d discovered it while he was in Toronto. He’d picked up a card that read “While in New York, stay at the Berkshire.” So he did.

He said that he thought I’d once phoned from the spot the Lexington used to be. “When you were on tour with those girls.”

“The Indigo Girls,” I said, trying to remember the name of that hotel.

“It was either the same hotel renamed,” said John. “Or maybe they took the building down and built a new hotel.”

He told me how he was walking along near his hotel and saw the Hickory House and he recognized it from an LP cover he had—maybe a Marian McPartland LP. Or maybe he discovered her by going there a lot, to the Hickory House: a steak house known for jazz. The first night he saw the place, he walked up to the door, but somehow felt that he couldn’t go in, that he’d be thrown out if he went in. An image from 1981 popped into my head—walking east along Bleecker with CBGB at the end of the street, on Bowery. I was heading for an afternoon show and actually, I didn’t know much about CBGB, but a guy I worked with (David Lester) told me a few things I might want to do while in New York. I’d been before, to New York, and I was going back for a second time, alone again, naturally. I mean, I was practically married, but I liked to travel alone.

John went back to the Hickory House the next night, flung open the door and told the maître d’, “A table for one near the music.” He was taken to a table for one right near the music and ordered a steak and went back many times after that. My mother went on at least two of John’s trips to New York, and he introduced her to the Hickory House and to Sydney the bartender, one of maybe six bartenders behind the huge horseshoe-shaped bar. One night John was sitting at the bar and Sydney introduced him to a member of the Modern Jazz Quartet. Sydney said, “John is an authority on jazz. You two will have lots to talk about.” But my father didn’t know much about the Modern Jazz Quartet. That’s all he had to said about that story. This was one of those compounding free-association conversations that included me asking, “Didn’t you see James Baldwin and Captain Kangaroo on the same day?”

Back to Rawlings, the fashion photographer John worked with. As the art director, my father picked the models they used for various campaigns. Nabob Coffee was a big account, and photos of Lauren Hutton were included in the selection for the shoot. Rawlings said something about wanting to use her, this Lauren Hutton, because she was new and there was something he liked about her—so, if John wasn’t opposed, he’d like to use her and my father picked her for the coffee ad, which was probably a national print media campaign in Canada and at that time anything national usually came out of Toronto and certainly not from an up-start art director from a Vancouver agency who went to New York to work with a Vogue cover photographer.

Actually, I wanted to write about a woman at Curves, the gym for women who hate gyms, where I work, Curves. I want to write a story called The Control Leg. I told Ronnie I was going to write it. She laughed. I told her I’d change her name and everything. She didn’t seem to care. She’s in her forties, very nice and friendly, and she frequently tells me strange things after she’s done her work-out. Good strange. She starts telling me about the self-tanning product she’s thinking about using and it becomes clear that she has tested it out on one leg, so I asked to see and she pulled up her pant leg. She was concerned that it looked a bit orange. And, yes, it did. There were a few other women getting ready to leave and they started trying to listen to what we were talking about, trying to figure out why Ronnie and I were looking at her leg.

I said, “Let’s see the other leg.”

She pulled up the other pant leg and we compared—her one normal, fair skinned leg to a now even oranger-looking leg, by contrast. I told her I like her usual leg, regular colour.

I asked, “What does Bob think?”

“He hasn’t seen it.”

“You’re hiding your leg from him?”

“Yes.”

“How much of your leg did you do?”

“The whole thing.”

I see an impression of Ronnie with the one orange leg, here and there around their house, in bed, in the shower. A composite of images of Ronnie hiding the orange leg from Bob.

“This is the control leg,” Ronnie says, gesturing towards the regular leg.

“If you decide to do it, what will he say?”

“He’ll wonder if I’m pulling away from him.”

“Really?”

“I think when people change things about themselves, their partners wonder if they’re trying to attract attention from elsewhere,” says Ronnie.

“I’ve never thought about that,” I say.

“He’ll ask if there’s anything we need to discuss.”

“Really? Wow. He knows how you feel about him, right?” I say, not really knowing how Ronnie feels about Bob, except that every time she mentions him, it is with such warmth that it seems certain that she loves him a lot.

“He’ll be wondering why I thought I needed to change anything about the legs he thinks are perfectly wonderful the way they are.”

“Do you know how long it’ll take before it matches the control leg?”

“No.”