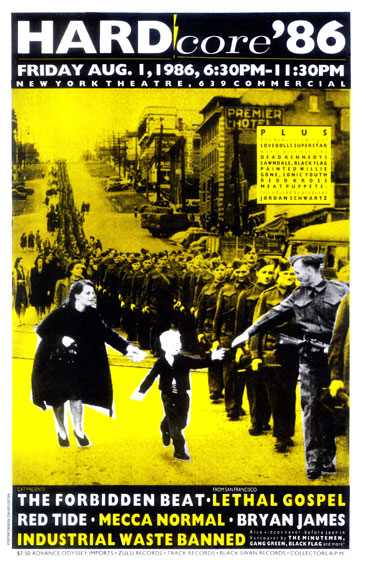

Every Saturday, we’ll be posting a new illustration by David Lester. The Mecca Normal guitarist is visually documenting people, places and events from his band’s 26-year run, with text by vocalist Jean Smith.

Every Saturday, we’ll be posting a new illustration by David Lester. The Mecca Normal guitarist is visually documenting people, places and events from his band’s 26-year run, with text by vocalist Jean Smith.

Characters In This Story Are Closer Than They Appear

“Why don’t you stop thinking about it?” her father says on the other end of the phone.

“Thinking is kinda what I do, Dad,” says Celia, thinking about why her father might want her to stop thinking.

“Dwelling on it isn’t going to change anything,” he says, trying to sound like he knows what he’s talking about. Fatherly advice. Celia isn’t actually asking him for advice—she never has. She has another reason for talking to him about these things, these situations, at this time. She is assessing his reaction; he would prefer she wasn’t thinking or talking about mental illness and personality disorders.

***

Celia needs an ending and she’s averse to endings—she doesn’t like goodbyes, doesn’t see why things have to end. Endings are consumer-based constructions; that’s what she wants to say to the women at the gym when they tell her she needs to figure out the ending of the screenplay, but now they’ve stopped calling it a screenplay. They’ve started calling it a film—a movie—to indicate to Celia that it does need to end. And they are pushing and pulling on the equipment with more vigor—frustration really—because it does seem that Celia is digressing, finding men worse than the previous one.

“Have you figured out the ending yet, Celia?”

“I might just be getting started,” Celia says, dancing to ABBA in the middle of the circuit. “Things are starting to get interesting.”

“You could have multiple endings and let the audience decide. You could have happily-ever-after or happy-on-her-own,” says Vivian. “Or maybe she’s just going to continue looking for Mr. Right.”

Endings are for Hollywood movies. One can only sit in a velvet chair in the dark for so long before one needs to go home and go to sleep. Satiation arrives by way of distraction from real life—the purpose of most movies. So long, daily concerns: I’ve gone trout fishing in an American movie theater.

Celia has been telling the women about her dates and short romances for years, episode by episode—they sweat, working out, ABBA plays. When the women arrive, Celia finishes what she’s doing on the computer, looking for possible ways to sell her screenplay. The women talk about the weather, and if Celia’s busy, she might just let them get started on their workout, but before long they try to draw her out from behind the desk, calling out from the chest-back machine: “Anything new Celia? Been on any dates?” They remember where a story ended and ask about a specific guy. “What happened with the professor?” And Celia might say, for fun, “Which one?” as she turns down ABBA, spins out of the swivel chair and saunters out to tell them a story.

***

“I think about these things because I’m trying to understand people, Dad.”

“People are difficult to understand, Celia. Why they do what they do is often beyond comprehension regardless of how long you think about it.”

“It isn’t one thing, one thought, going around and around in my head all day,” says Celia, wishing she’d been able to resist defending herself, thinking about how her father distances himself from the word “people”: they do what they do. “I make progress in understanding what happened by thinking about it,” she says, sounding wikipediatric. Limp. Celia wonders if he gets it, gets it—got it—if he’s ever gonna get it at all. What she does. She wonders if he gets it on a subconscious level. What is she afraid would happen if she asked—would they stop talking again? For three years, Christmas cards arrived with only her mother’s name on it. Love, Mom. It was as if he’d died. Celia woke up most mornings and slowly worked her way to this one thought: Her father hated her that much. She wasn’t worth knowing. How would she feel if one of her parents died during the time of no communication? No communication. No communication.

She’d been trying—awkwardly—to show him that she was responsible. She’d quit drinking. She wanted him to know she was concerned—she wanted to help make a plan for them in their old age. She’d simply asked him where they were going to live when they could no longer live where they were. He blew up. He took it personally.

“Do you know how many pills I take, Celia?” She didn’t answer. He asked it over and over : “Do you know? Do you know? Do you know?”

Celia didn’t answer.

“I take one tiny pill,” he finally said. “That’s it.”

It was fear, she realized years later. When he was afraid, he got angry and yelled at everyone. That was what fear looked like. He was very frequently afraid, fearful, frightened. He yelled a lot.

Celia still had the tape recorder attached to phone after interviewing Godspeed You Black Emperor! for Your Flesh. She’d been staring at it—the tape recorder—while he yelled. He was telling her if she was so bloody concerned about old people’s homes, she could bloody well get herself on a list. She flipped on the tape recorder and watched the cassette fill with vitriolic bile—evidence! Eureka. Finally.

“I wouldn’t have your life for a million bucks,” he said over and over, and Celia kept thinking that the statement defied logic. If he was given a million bucks to have her life, then her life wouldn’t be her life. She was poor. End of story. How could he have her life and a million bucks? It didn’t make sense, but he kept saying it.

She doesn’t want to defend herself. She forgets why she isn’t supposed to defend herself. She wonders if not defending herself while not knowing why she shouldn’t defend herself has the same result as not defending herself and knowing why she isn’t. Doesn’t.

Celia wants to say something more substantial about all this thinking. To convince her father. She knows she shouldn’t try to impress him, to try to get him to understand her. Seeking male validation. This is the story that will not end unless she behaves differently. “By understanding what happened, I’m less likely to have the same thing happen again.” This too sounds insubstantial without an example. Evidence is required.

***

Celia writes in boxes on the screen, looking for boxes that feel good to her. She likes to write in email boxes—it starts out being to a specific someone. That’s one way to get started; then she carefully highlights the recipient’s name and deletes it, but it is during this process that the program has started crashing. Celia joins Facebook. She reads comments, but doesn’t feel compelled to add anything. Yesterday, Rhonda took a poll: spiders—catch and release or kill? Approaching 24 hours later, 40 people have responded: “I’m the catch-and-release type.” “I agree with James.” “Ditto, Patty.” Celia thinks about saying “Ditto the guy who said ditto Patty,” but she wonders what that will say about her. She isn’t part of their group. She isn’t part of any group. In an email box she writes, “I can hurt a fly, but not the tenacious spider, creator of web across my open doorway. The web traps the inbound fly that I then don’t have to kill—leaving me, yet again, happily on the outside of another equation in nature.” She pastes it into the comment box, but she can’t post it. She’ll look like a pretentious something-or-other.

***

“Men don’t arrive in front of you blaring out all their flaws and misfortune,” says Celia to the three women working out. “They don’t just tell you what’s wrong with them. It takes time to get to know them, to watch them in action.”

“I thought he did tell you there was something wrong with him. Isn’t this the one who told you he had some problems on the first date?” asks Cynthia.

“Well, at least I know you’re paying attention,” Celia says, laughing. “Yes he did, and I should have heeded those warnings.”

“Why didn’t you?” asks Cynthia, from the leg-press machine.

“This is where it starts to get complicated. Do you mean why doesn’t Victoria heed the warnings or why didn’t I heed the warnings?”

“To tell you the truth Celia, I’m not sure which is which. You go out with these guys and then you write about what happened using the name Victoria as a character in a screenplay, but the screenplay seems autobiographical to me.”

***

“They’re just stories, Celia,” Darren says after Celia has interrupted to ask him why he’s telling her about horrible people in his past—awful men without morals, reverse-Mohawk-mullets, a bunch of drug addicts living in a basement with rats-the-size-of-cats gnawing in the ceiling, having sex with underage girls, out of their minds on drugs, trying to flush stolen property down the toilet when the cops come knocking. Celia is trying to get to know Darren and she wonders why he’s telling her these things, so she asks. “Why are you telling me these stock stories about crappy things? Is it because you didn’t get enough sleep last night?”

“They’re just stories, Celia.”

“Stories are usually told for a reason. They have a purpose,” says Celia, and Darren doesn’t like this too much. She watches him go dim and empty inside, as he explained that he would if he felt hurt. Celia thinks it is very odd that she needs to tell an English professor that stories are told for a reason and she’s trying to remember what he told her she’d need to do to bring him back. Leave him alone? Ask him a question? Do a little dance? Get down tonight?

This is when he changes course and starts informing Celia that she needs to forget about screenplays and music to concentrate on painting, but not the paintings she’s been doing recently. “You need to do murals. Really big murals. You need to do hundreds of sketches for many months, and the mural will tell a story.”

Celia puts ramen in her mouth, uneasy, not wanting to defend herself, trying not to say who she is. Who she was. She allows Darren to show how he gets when he’s been offended. Hurt. She has hurt him. And now it’s time to pay. Not for the ramen. The ramen she heaps between splintery chopsticks, shoving it in her mouth, biting off a clump, letting the rest fall back into the bowl of over overly salty broth and fatty chicken.

“You need to get on with your career. Make a name for yourself. Re-invent yourself as a painter.”

“People know who Celia Sonar is,” Celia says feeling idiotic, knowing it isn’t really true—but enough people know. Enough for her.

“Do you ever feel like you’re waiting for something?” asks Darren, leaning toward her. “Waiting for the next thing to happen?”

As if by asserting this construct—this question—across the ramen-splattered table he has introduced validity to his next statement. Celia looks at the ramen hieroglyphs strewn on the arborite surface. A fossilized seahorse. The profile of a Toulouse-Lautrec courtesan—the hair, the forehead, eyes downward.

“What do you want most out of life right now?” Darren asks, intending to imply that he has the answer. The answer is forthcoming. He’s asking if Celia has ever entered the state of mind of wondering what is going to be the next thing, who will be the next person, to arrive and change everything, to start the next phase. Celia’s thoughts on this are complex. Not overly complicated, but unusual, and they are revealed when she answers, although she understands that Darren won’t get it. He’s not gonna get it, get it, get it—ever at all. Even with a Ph.D. and possibly because of his Ph.D. in English literature.

Celia sees him as a guy on a TV infomercial or an evangelist, setting her up to see things his way. She wonders what he thinks she’s going to say—sell my screenplay, get on Oprah, find a better job, be successful. Fall in love. Something superficial like that. And then he can correct her wayward thinking, her flawed goals and offer her direction in her rag-tag life of unfocused professional failures, not to mention her inability to find a man.

“To feel content,” Celia says, having made a decision to say feel it rather than be it. She decided to say to feel content instead of to be content. “To be” implies too much about time, amounts of time being replaced with other amounts of time, which is more what she was thinking, but for now, for the purpose of this interaction over bowls of ramen at a high-end Japanese restaurant in the middle of the day, “to feel content” is enough. For now.

Darren’s elbow slides out sideways on the table. He props his head up with his hand, eyes opening and closing separately from each other.

“Is there anything else going on with you other than a lack of sleep, Darren?”

“Nope.”

“No?” Celia asks, her heart-pounding in a most uncomfortable way. She wants to run away, but she needs to know. “There’s nothing else going on with you?”

“OK. I took two clonazepam because I was nervous about seeing you.”

***

Celia plays the tape for both her best friends. They stand and listen.

“You see what I mean?” Celia says, arms crossed over her chest. The two friends look at each other, understanding that Celia must hear something else, something other than what they hear.

“Celia, it just isn’t as bad as you think it is.”

“Listen. He’s screaming at me,” Celia says. “You’re kidding, right?”

“Celia, you hear it based on your childhood experience—you were afraid of him. That’s what you hear now.”

***

Cynthia wipes her face with a white towel and tosses it in the hamper on her way into the changing room. She stops in the doorway. Turns and asks, “Are you going to see him again?”

“The professor? No,” Celia says emphatically, standing near the computer with her arms folded over her chest, thinking about the spider and the fly. “Are you kidding?”