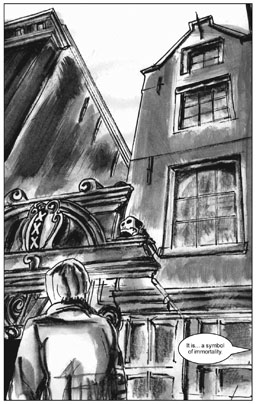

Every Saturday, we’ll be posting a new illustration by David Lester. The Mecca Normal guitarist is visually documenting people, places and events from his band’s 26-year run, with text by vocalist Jean Smith.

Every Saturday, we’ll be posting a new illustration by David Lester. The Mecca Normal guitarist is visually documenting people, places and events from his band’s 26-year run, with text by vocalist Jean Smith.

I was walking over to the candy store last night, feeling absolutely gleeful. I don’t think I’d realized how much the last in a series of tests for cancer had been weighing on me. My brain had been trying to get me to forget about the appointment the day before. I couldn’t remember what time I was supposed to be there. I’d left myself notes and sent myself emails, unfolding and re-reading the info sheet in my purse for the directions to the hospital—some sort of block. An urge not to go to the appointment. Fear, I suppose. And I don’t cop to fear lightly.

At the hospital, I kept wanting to ask someone for an ativan. The first person who called my name took me into a small room to do the intake paperwork. I waited for her to stop asking me questions about where I lived so I could ask her for an ativan. Panic rising, swirling—reducing clarity of thought. As she was asking me questions about where I lived, I realized she wasn’t going to give me an ativan—she was a Kafkaesque clerk of sorts and I’d have to find a nurse to get an ativan and as I was thinking this, she was handing me a clipboard, pointing down the hall and saying, “Nurse’s station.”

I walked 20 paces, past an office area, into a room with lots of beds full of sleeping people. I stopped and watched a nurse trying to roll a big woman from her side onto her back, saying, “Let’s turn you over doll, your blood pressure is dropping.” The machine beside the bed was beeping, just like on House. The urge to flee was very strong—panic attack ahoy. A man’s voice said, “Wait. Back up. Over here.” I’d gone too far. Hospitals are their own weird world that I avoid, and a lot of what they do there doesn’t seem obvious to me.

When I’d first arrived at the doors to the clinic, after following a red line through the hospital and, at one point, veering down a hallway to look at aerial photos of North America at night—major areas of population lit up—I started to look for the tiny island of Tobago off the coast of Venezuela, thinking about 1979, walking down a dark road with a guy named Cops who had never heard of the Rolling Stones, remembering the sensation of it being so dark that I couldn’t see my feet on the road and I couldn’t see Cops because he was black. He was just a deep voice to my right. At 19, I’d never been beyond the USA, and I was trying to fathom that there were people on earth who had never heard of the Rolling Stones.

Mecca Normal, having been asked to perform Fall songs at a tribute for the Fall, arrived at the El Mocambo in September 2001 [citation required] fully aware of the room’s historic significance as they wandered around, trying to imagine the Rolling Stones playing such a tiny venue in 1977 [citation required]. Weirdly, Mecca Normal—who were not fans of the Fall—were confirmed to open for the Fall two months hence at the Knitting Factory in Hollywood [citation required], where singer and recovering alcoholic Jean Smith would opt not to say hello to Mark E. Smith, who spent much of his time slumped in a corner backstage [citation not required], and while onstage, he harangued his band [citation not required] to a degree that Smith [Jean] found uncomfortable to watch [citation not required]. Fans of the Fall were not particularly enamored with Mecca Normal’s set [citation not required], but after the show, the bass player from the Fall kissed Smith [Jean] [citation required]. Actually, Smith [Jean] can’t remember exactly what happened because, at 50 years of age, some things have disappeared from her memory [can’t recall if citation is not required]. Smith [Jean] recalls that the story of the bass player—or maybe it was a guitar player—ended up in an online article by Fred whose last name currently escapes Smith [Jean] [citation required]—a journalist she respected. Smith [Jean] contacted Fred and asked him about his source, and since she didn’t mean for the kiss-thing to be a public statement, could he please remove the reference in his article. At that time, when all this happened, Smith [Jean] did remember the whole story because she’d quit drinking a year prior [citation not required], but it was not something that she ever would have said to a journalist—it was related by email to a friend, who, in his enthusiasm, wrote a review for a group of online Fall fans and included the part about the kiss [citation required], and it got onto some sort of forum [citation required]—all of which was fine until the journalist copied it [citation required].

While Smith [Jean] herself is not actually averse to kissing and telling, there tends to be a reason for it, and being kissed by a member of the Fall [citation required]—not a big wet kiss [citation not required]—didn’t seem to have a purpose, until now, when the details are cloudy [citation not required].

I arrived at the clinic—double doors with a stop sign that said Do Not Pull. I looked through the window and saw people in beds with chrome railings, patients in blue gowns, nurses, drip bags on poles. I would have felt better if I’d seen House hobbling around in there. No House. That’s bad, when seeing House would be comforting. I stepped back from the door and looked at the chairs lining the walls. It seemed like I should check in somewhere. The people sitting didn’t look half as nervous as I felt, so I figured they must be waiting for a patient. I looked at the signs again, at the perfectly good door handles. Stop. Do Not Pull. Backing up again I saw the automatic door button and pushed it. I walked in, looked into the first room where there were people under blankets sitting in lazy-boy recliners reading newspapers—they had IV needles in their arms, like they were giving blood, which I can’t do because I was living in England in late ’80s and there was a tainted blood scare and when I was living in Tucson in the early ’90s and I needed money for rent and I’d heard about people selling plasma—mostly illegal aliens and alcoholic transients that hung out at the Tap Room in the Congress Hotel—and since I was basically an alcoholic alien hanging out in the Tap Room, I went to sell plasma, too, but they took a sample of my blood and told me it had too much protein in it.

It probably didn’t help that I hadn’t eaten for 36 hours and hadn’t had coffee or water that morning. I was hungry, thirsty and had a headache. Once seated in the lazy-boy recliner unit, another intake clinician asked more questions. I checked that the name on my wrist-band was my own, and she asked me how much I weighed. “After yesterday, about 105 pounds,” I said. She asked if I had any pain and I said I had a headache. She looked up from her clipboard and said, “Really?”

“Yes,” I said. “Really.” I hardly ever get headaches. It was from no food and mostly, no coffee. I’d made a tiny cup at 4:30 a.m., even though the instructions said nothing by mouth after midnight, I let a tiny amount of coffee dribble down my throat and held the remainder in my mouth, hoping to absorb caffeine that way, before spitting it out. It hadn’t worked.

“On a scale of one to 10, how bad is the pain?” she asked.

I was in a hospital. Pain was everywhere. Did she mean on a scale of one-to-10 per square mile or based on my own experience with pain, which is thankfully very small?

“Six,” I said.

“Five?” she asked, in response.

“OK, five,” I said. “That’s what I meant to say.”

The other three lazy-boys were occupied by men, two of whom had proudly answered, “My wife,” when the clinician had asked who was coming to pick them up after. What kind of stupid answer is that, and why don’t I have a wife? The guy sitting next to me seemed OK, but he was blinking rather a lot. The clinician asked him how he was feeling, and he said he was nervous. The clinician repeated the word as she wrote it down, and then he changed his mind and said, “Apprehensive.”

The clinician chuckled, as she’d appreciated a variation on theme. A chance to write something other than nervous. The guy started blinking more rapidly as he noticed her entirely self-referential reaction to his plight. She asked if he’d taken any meds that morning, and he said he hadn’t taken his psychotropics, which I don’t know what that means, but anything with the prefix psycho has me on edge these days. Maybe someone could get him an ativan, too. My doctor came in and spotted me. “Let’s boogie,” he said, and I began struggling to get out of the lazy-boy. “Bring your blanket with you,” he added.

“I shall,” I replied, feeling the urge to elevate the level of discourse in the room as I balled up my flannelette blankie and shuffled across the room in baby blue foot-encasers and doubled-up hospital gowns.