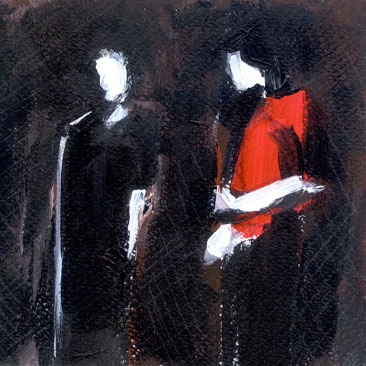

Every Saturday, we’ll be posting a new illustration by David Lester. The Mecca Normal guitarist is visually documenting people, places and events from his band’s 26-year run, with text by vocalist Jean Smith.

Every Saturday, we’ll be posting a new illustration by David Lester. The Mecca Normal guitarist is visually documenting people, places and events from his band’s 26-year run, with text by vocalist Jean Smith.

David’s illustration (July 2010) is of Mecca Normal’s first performance (July 1984). The text is an excerpt from Love Wants You.

Sex with Ryan feels stale, like reviewing the minutes of a meeting that adjourned after agreeing—on paper—how to have sex. This is how we do it.

Lying beside him, my hand on his chest, Ryan says, “I have boundaries and I need space. I’m not into drama.”

Slowly, recalling that some people don’t like to be touched after sex, I take my hand off his chest. I assess where else my body is touching his. At the hip. My left foot. The hair is still swinging on the TV. He’s playing a shampoo commercial over and over.

“Women tend to see me as a palette cleaner,” says Ryan.

“What does that mean?” I ask, turning onto my side to look at his face, elbow propping up my head.

“When their main squeeze splits,” Ryan says, staring at the ceiling. “They come to me for sex until they find another lover.”

“And that’s OK with you?” I say, a set of nuances—physical and emotional—drop into my mind. Plump women with belly-button rings, Asian-themed tattoos and Bettie Page bangs—naked save for black garter belt and fishnet stockings with holes—are on top of Ryan who is flat on his back, a mere palette cleaner of a man.

“In a way,” says Ryan. “Hey, I need a smoke. Let’s get up.”

We sit at the top of the stairs, above the alley. Ryan picks the other half of his cigarette out of the ashtray and stiffly strikes a wooden match. Sunlight illuminates the unfurling lines of blue-grey smoke as it pushes back into the apartment. Ryan inhales deeply. I turn the other way—embarrassed by his need to suckle the nipple-filter for toxic nourishment. He exhales an internal venom that mixes with acrid poisons off the tip—the slow ejaculation of excess in his self-gratification process. A garbage pail holds open the door—non-productive popcorn kernels, squeezed-out tea bags and coffee grounds give off a withering scent of lethargy. Small flies, too young to buzz, swivel, blue-winged in the sunlight. Ryan talks about his temper and his financial problems. “I don’t stay in jobs long because I don’t handle authority well.”

I look down into the alley, thinking about Ryan losing his temper on the job. Fingers pointing, raised voices, doors slamming. I can see this scene from above—Ryan is a Playdough figurine in a shoebox diorama. His Gumby-Pokey feet stuck to the floor.

I get up and look around the kitchen. Counter-space covered in chipped thrift-store dishes, rusty cutlery, a badly-dented aluminum pot with a loose plastic handle. Guys I’ve chatted with online tell me I need to accept things for what they are—”Don’t keep trying to figure out what it means, or what it might mean. Accept it for what it is in the moment.” Guys instruct me to think this way because it suits their purposes. They assume that I’m thinking in some way that might impede their progress. I am in the moment more than I probably should be.

In crisp white printing on Ryan’s chalkboard: “2005 is the year to take care of myself.” I open the fridge. A waft of sour milk from a crusty-spout of two-percent next to the Creamo. On the rack below, two scallop-shaped moulds of red Jell-O setting. Crimson dribblings splattered across the bottom shelf—otherwise empty. I close the fridge and go back to the sunny corner to find my packsack.

“I think I’ll go to the gym now,” I say, swinging on my completely full packsack. Ryan looks out the window—a confused twitching between his eyebrows prompts me to ask, “What?” He doesn’t say anything. I ask again. It’s too early for either of us to be acting like this. Way too soon for me to be asking what.

“I’m not sure what this is,” Ryan says.

“Well, there isn’t much to go on.”

“I suppose not,” he says.

“Do you want to sit down again and talk?” I ask.

“Yes,” he says, all serious.

“May I have another cup of tea?” I say.

“Do you mean now or some other time?”

“Both,” I answer.

Ryan smiles and goes to the kitchen. In the draggy slouch of his shoulders I think I see regret—for what? The sex? Or instigating this process. I don’t have anything I need or want to say. I take off my packsack and sit down. Ryan puts the badly dented pot on the stove—no lid—he waits for it to boil.

“Do you take milk in your tea?” he asks.

“I do, but your milk is off,” I say.

“Had a look in my fridge, eh?” Ryan says.

“Just doing a bit of research,” I say.

“How about Creamo?”

“Sure,” I say. “Creamo works.” The fridge opens with the plastic against metal sucking sound we hear and ignore dozens of times a day. My mind creates the acrid smell of sour milk—I’m too far from the fridge to smell it, but there it is—perched like a hungry hawk at dawn in my short term memory. Waiting for light to hunt by.

Ryan shuffles back with two very full mugs. “I was with someone earlier this week,” he says, setting my mug down on a CD coaster. I pick up the mug and hold it with both hands. Ryan sips his tea noisily and says, “If you’d asked, I would have told you.”

In the sunlight, steam particles look like cubes of rainbow prismatics. I’m wondering what band I’m using for a coaster. Local? Major label?

“What else should I have asked?”

“I’m not going deny myself pleasure,” he says. “In the ’80s, we had sex with our friends, then we returned to being friends.”

“We’re not friends, Ryan,” I say, thinking, “I didn’t have sex with my friends in the ’80s. I had drunken one-night stands with guys who didn’t speak English. I had inappropriate half-baked romances with lunatics. I had sex with guys I never wanted to see again.”

Ryan gets poetic, “I’m like a new shoot, growing. I’m on an upswing.”

I am being warned. I might thwart his upswing. Ryan is 37, tall, skinny, weird skin. I leave the tea, stand up and put my packsack on again.

“You know a lot about my psycho-sexual background,” he says. “So play nice.”

He is talking to me as if I’m someone else—someone he knows, understands—as if I’m part of the group that he represents. Didn’t he notice that I don’t have piercings and tattoos—that I’m not imitating a 1950s pin-up girl who’s using him as palette cleaner?

Going down the narrow backstairs and into the alley, all familiar territory, temporarily skewered by this re-shuffling. My hair is a mess.

At the gym, I drop things on the locker room floor. My shampoo has leaked onto my towel. I can’t do my full workout. Distracted. This disruption. I will return to what I need and utilize all new experiences. I am okay. He has not altered me.