Kristian Hoffman and Lance Loud met in high school back in the early ’70s in Santa Barbara, Calif. After starring in PBS cinéma-vérité documentary An American Family, they formed the Mumps, moved to New York and shared Max’s and CBGB stages with all the legends of the punk/new-wave explosion of 1976: Television, the Ramones, Talking Heads and Blondie. Hoffman and Loud also had front-row seats for the Mercer Arts Center incubation of the New York Dolls, before that. In our book, that grants you unlimited license to open the floodgates. Fop (Kayo), Hoffman’s latest solo album, is an ornate masterpiece of baroque pop, well worth your attention. Hoffman will be guest editing magnetmagazine.com all week. Read our new Q&A with him.

Hoffman: I don’t know about you, but I have a complicated relationship with weeping. It’s like the mistress I wish I didn’t have to confess to my spouse. And yet it’s such a big part of my emotional makeup, I’d feel incomplete if I couldn’t access that orgiastic self-involved ejaculation of tears, projected or otherwise. I’m not pretending to any sort of discriminatory aesthetic. I democratically weep as much at a Charmin commercial as at a Sally Struthers/Biafra-baby info-sploitation appeal. Elton John’s “Sad Songs Say So Much” may have been one of the most infelicitous marriages of lumpen lyric to saccharine melody in musical history, but still, it’s hard to dispute the notion!

I don’t know if it was post-Manhattan Project malaise or simply a post-industrial sensibility, but many of my generation were born into a before-the-fact mourning as readymade as any Marcel Duchamp latrine, a sense of inevitable endtime as palpable as the Monkees’ last inglorious descent from the realm of the top-40. As the New York Dolls quoth in “Bad Girl,” “A nuclear bomb is gonna blow it all away/So I gotta get some lovin’ before the planet is gone.” Our unease (or dis-ease, if you will ) was (and, in some cases, still is) instinctive, not earned by actual experience, but as feral as the scent of a hyena to an abandoned wildebeest calf. And yet this prefab faux-empathy has borne so many life-enhancing experiences, I can’t help but think that the badge of being a confirmed weeper is the proud-lion rampant crest for those who would retrieve what is left of our wounded planet and sorry community and heal it through artful, forthright lachrymation.

Whether that be fanciful self-aggrandizement or a tearful manifestation of an all-too-certain apocalyptic diagnosis, I confess have always had a soft spot for weepers that renders me as damp and flaccid as the kleenex on the warm ironing board of the housewife Netflixing An Affair To Remember for the umpteenth time. If there is such a thing as “wistful,” I’m pretty darn full of wist! I’m a “weeper” target market!

So let me show the dear reader (if any!) the unencumbered pathway towards sheer, music-inspired weep-i-tude. It’s a good place to be. It may not actually inspire people to “Get Together” (as suggested in one of my favorite “weeping toward spiritual evolution” ’60s nuggets by Chet Powers (or Dino Valente?) of which I have way too many versions, including the favorite Lennon-Sisters-by way-of-Paul-Revere “Family Affair” 45), but I can say that while you’re pleasurably disconsolate in Weeper City, you’re likely keeping out of trouble! It’s hard to do much damage while you’re huddled in the fetal position next to the stereo. So, weeping? I recommend it. Never was a despondent low such an easy access to a delirious weepfest high.

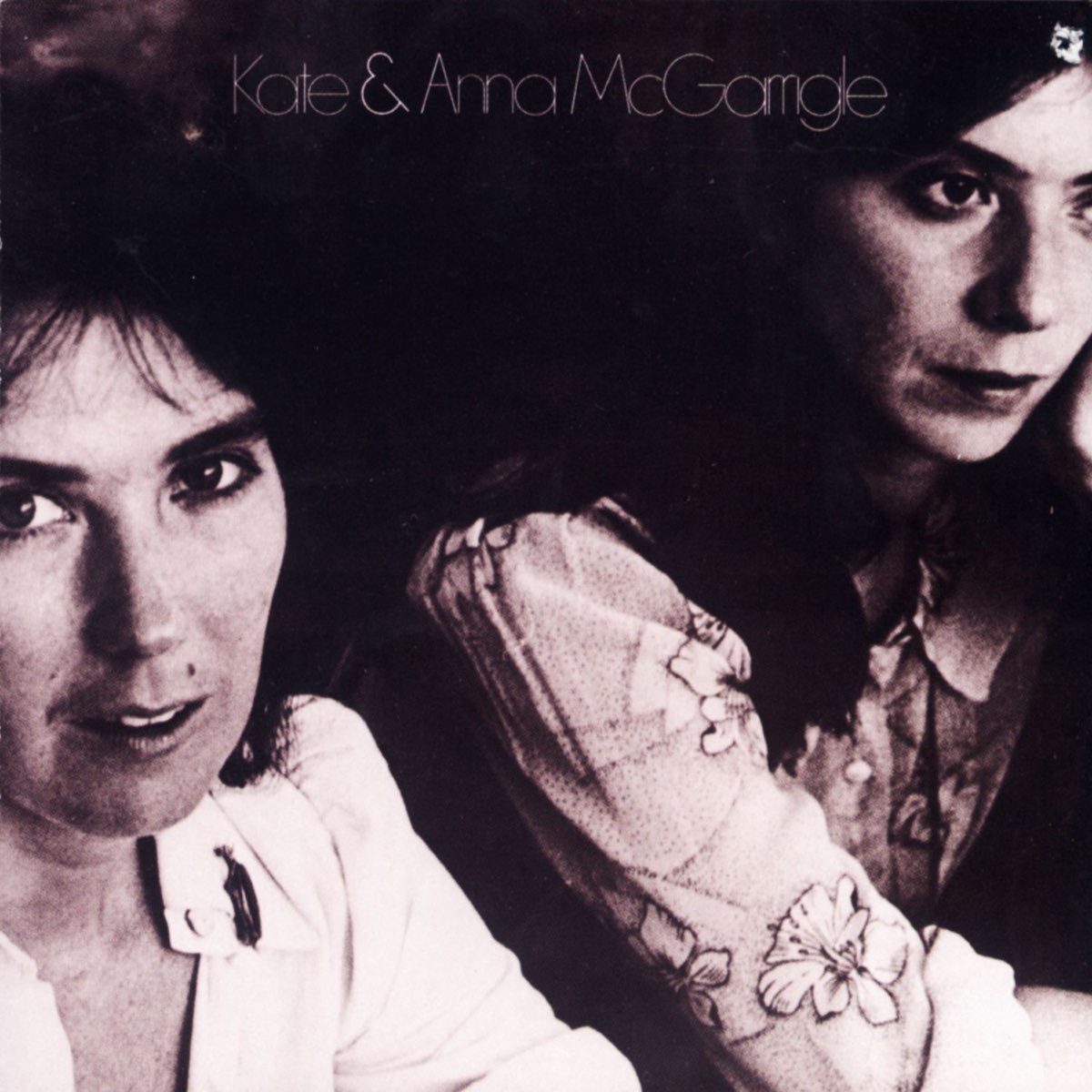

“Go Leave” by Kate McGarrigle. All-time weepfest champion. Something about it renders all other entries in the genre hopelessly prosaic. It’s like distilled haiku “easy access” weepitude. I’ve said before the McGarrigle Sisters have me at the first vocal quaver, because their uncanny timbre is like the sound of impossibly delicate Christmas ornaments dropped and shattering. It’s the breaking of the heart of hearts. “Talk To Me of Mendocino,” “Kitty Come Home,” “Heart Like A Wheel” (especially with the verse that admirable-but-misguided McGarrigle champion Linda Ronstadt inexplicably deleted: “They say that death is a tragedy/It comes once, and then it’s over/But my only wish is for that deep dark abyss”)—these are all gushing gates to the land of weepery, some tragedy-free, seducing your tearducts with the mere wist of past joys not to be regained. But “Go Leave” is something different. It is the ailing heart, left naked in the rain. A lone voice with guitar, an aria sailing the arc of love like Charon on the Styx, admitting the inevitability of the fires cooling, and speaking the unspeakable: “Go leave/She’s better than me/Well, at least she’s stronger/She’ll make it last longer/That’s nice for you.”

Lance Loud and I received this record when we lived together on Eighth Avenue and 23rd Street through the graces of his sometime reviewing position at Rock Scene magazine. We never really recovered. Even though even then we both agreed that the last verse is a supremely lame, corporate-interference-type tacked-on happy ending—“Could it be that you are stalling?/Hearts have a way of calling when they’ve been true” (cringe!)—the rest of it is such a transcendent stairway toward the spiritual cleansing of a good sniffle that it’s just Weeper Godhead. The resolutely terse acknowledgement of the defeated: “That’s nice for you” lived on in Lance’s and my vernacular for decades as the hallmark of resigned romantic despondency, informed acceptance of inevitable tragedy through supreme intellect and artistry, which only made the tears burn hotter.

“Myriam And Esther” by Phranc. This one, like “Go Leave” is such a distilled essence of the human condition known as cognizance: the pain of recognition that some things are predictable and the pain of being an informed-enough witness to confess knowing the depth of the undeniable rudeness of being. Again the words are stark, precise, as is the lone guitar, yet all are lovingly sculpted into a worshipful ode: Phranc’s two grandmothers passing inelegantly into what may be the comfort of the living unconscious: “She can’t finish her sentence, but she finishes all her peas/She doesn’t recognize me.” Being left witness may not be the more rewarding position. By the time you get to “Some people grow old gracefully, and some die in their sleep/But Myriam and Esther weren’t blessed with that luxury.” Even the warmth of Phranc’s sweetly unaffected and warmly sonorous voice won’t save you from that unencumbered carpool lane to Weepville, that the heart-wrenching cruelty of destiny is painfully, achingly routine. Michelangelo saw the slave in the marble; Phranc pulled the weeper out of the ether.

Did you expect Ray to be higher up on this list? Of course you did! So did I, in a way. Because Je Ray adore! But access to the Goddess Lachryma isn’t a fucking competition! It’s an equal-opportunity party! So please don’t misinterpret the sequential numbers as presumed appraisals of weepy worth; it’s just the order the songs occurred to me in. In any case, of course, Ray Davies’ meisterwerk “Waterloo Sunset” is a supremely mordant, romantic observation of the Observer, observing those worthy of observation even as he knows he himself will never be deemed worthy to be observed. That loneliness is the DNA of the tragically informed. A little knowledge is indeed a dangerous thing! And of course, “Days”—one of the most perfect songs ever written, because it is at once sincere, gorgeous, affectless and knowing—should be on here, but, to me, it is too resolutely a triumph of art to invoke tears. It’s like Jobriath’s “Gone Tomorrow”; though it ably and poetically is a witness to tragedy, it does not succumb to tragedy. It invokes joy at the very forward impetus of life experience. “Autumn Almanac”? The seemingly derisive portrait of the impervious borders of possibility still has a poignant romanticism that keeps it just this side of weeperdom: “This is my street, and I’m never going to leave it” is at once bristling against the obvious limitations of predestiny imposed by caste and economics and yet celebrating the warmth of community. Even “Sitting In My Hotel” was a nominee; so deliciously moribund and yet ultimately just observational and dipsomaniacally romantic. “Where Have All The Good Times Gone”? Gooseflesh in its gloomy discernment (especially the wistful Bowie version, so canny about nostalgia as poison), but it’s just too perky and assertive! So to me, it is “Moments” that is Ray’s transcendent weeper. Ironically, from a “comedy” about a penis transplant(!), when Ray quavers in his best Bolan vibrato, “I say I’ll never do you wrong and then I go and do the same again”—with acknowledgment of the tragedy of his own predisposition—well, it may not pluck the heart strings, but it sure mists the eyeballs.

I was, for good or for ill, introduced to Sandy Denny’s “Who Knows Where The Time Goes” when my mom bought the Judy Collins version, which is not terrible in and of itself. I’m not ashamed; that version is glorious. I think Judy was sleeping with most of the people in her band—titillating! And onetime Monkee aspirant Stephen Stills still had, at that point, as Life magazine once said of John Kennedy, only a “modest displacement.” In any case, Lance and I soon discovered the source, Fairport Convention (damn, Iain Matthews was hot!), whose fantastic hymn to cynicism “Meet On The Ledge” I was once lucky enough to sing with Robert Mache and Susan Cowsill and several errant Continental Drifters. Sandy quickly became an idol, and her LP with the searing “Solo” and wist-filled “Whispering Grass” became a timeless favorite. But somehow the smokiness of her voice didn’t lift her own version of “Who Knows Where The Time Goes” into ultimate weeperdom, although the composition itself is beyond reproach as a penultimate tear jerker. No, to me, Sandy’s ultimate weeper is “Next Time Around,” which seems superficially opaque but is so mournfully evocative in tenor and arrangement that it almost doesn’t matter what it’s about. The soaring strings steeped in reverb, the disconsolate-but-defiant resignation in her voice, as if nothing will ever be better: the high violins streaming down like rain (or tears) in the third verse, the echoes of the Johnstown flood, which was when abject tragedy was first made media fodder in the burgeoning press machine. All were a perfect recipe for tacit weeperdom. “Because of the architect, the building fell down/Smothered or drowned, all seeds which were sown/Then I’ll turn, and he won’t be there/Dusky black windows to light the dark stair/Candles all gnarled in the musty air, all without flames for many’s the year.” It’s just the cemetery chill of waning emotion made aural. The fact that it is a cryptic love lament to her then boyfriend (and middling talent) Jackson C. Frank actually makes it weirder and more intriguing, and it almost makes one forgive the line “Nothing could change you to Theo the sailor, who lives in his lair.” Holy McGarrigles: This weeper transcends meaning, lyric, context, and intent, and it instead ends up pure tears by sheer weep chutzpah.

Brit beat wist! It may seem odd that the soul-illiterate, skiffle-piffle percolatin’ sound that longed to cross swords with Americans as trifling as Annette Funicello and as transcendent as Chuck Berry could enter into the realm of classic weepers, but weeping is an equal-opportunity employer. And weeping spoke swimmingly to those struggling to escape the rusty grey environs of Manchester or Liverpool, as many kitchen-sink movies of the era (Poor Cow, A Taste Of Honey) can attest. The weepiness of these songs is refreshingly direct, free of mock poetic obfuscation and often enhanced by otherwise ruddy and coarse seeming (and hot!) individuals climaxing into angelic falsettos at unexpected intervals. Favorite weepers from this era for me are “Each Time” by the Searchers, with a strange, murky production so different than the Beatles’ crisp clarity. It’s not a wall of sound; it’s more a dark forest of sound. This is one of those songs that are perfect break-up, sing-along duct cleansers. Just try to sing along with it in the throes of a bitter separation; if you can make through the “No matter what you do, I keep forgiving you” to the orgasmic falsetto heavenward leap of the words “Each ti-i-i-ime,” it’s sure to flush your gutters. Ditto the peregrinating, breath-challenging ululations of the Searchers’ “Goodbye My Love.” Even their Bacharach bounce on “This Empty Place” is redolent of weep-worthy estrangement. Other candidates in this arena are Peter And Gordon’s deceptively buoyant reading of Sir Paul’s “I Don’t Want To See You Again”; your voice is sure to crack and dew drops are sure to form every time you try to karaoke your way through the title. P&G’s “I Go To Pieces” (from which I stole the chorus piano figure for my own “Morose Colored Glasses”) and, of course, “I’m Only Dreaming” by the Small Faces. Later candidates come from Terry Reid’s underrated, weeper-filled sophomore LP: “Stay With Me Baby” makes a primal hymn to desertion of that classic (which Bette Midler bludgeoned her usual unforgivable hobnail boot way though), “July” is an almost Sade-like delicate foreplay to a comforting round of sniffles, but oddly, it’s Terry’s take on “Rich Kids Blues” that, even though midway through it turns into a sub-Zeppelin plodding organ jam, would be the hardest to sing along to without breaking down.

In fact, taking a brief detour from the Brit beat topic, there should be a cross-cultural contest for which is the most unlikely song to make the recently reluctantly single crack into shuddering sobs before finishing the song. Rod Stewart’s atypically restrained take on the subtly suicidal “Dirty Old Town”? The Merry Go Round’s “You’re A Very Lovely Woman”? One vote for me would be ABBA’s “When All Is Said And Done” from their transparently divorce-addled (and thus most emotionally satisfying) album The Visitors. In the album’s title song, who’da thunk our sweet ABBA would be singing with their typically Norse-clipped consonance about waiting to be committed to Bedlam? I got this album when I was about to break up with my then BF of seven years, Bradly Field of Teenage Jesus And The Jerks. I can remember making the bed in the morning and singing along with “When All Is Said And Done”; the melody is as pop-perfect as “I Only Wanna Be With You,” and the lyrics frame ABBA’s pretentions to topical adulthood as hopelessly mired in their laughably inept ESL kindergarten appropriations of American vernacular. “Slightly worn but dignified and not too old for sex” should be a howler. But just try singing along with “Neither you nor I’m to blame when all is said and done” when you’re contemplating leaving your impossibly charismatic but deafeningly belligerent junkie-sociopath boyfriend, and I think you’ll stop fluffing the sheets, collapse onto the stripped mattress and just grab your bewildered runt of a Burmese cat named Bunny for a good sloppy bawl.

Joni. Oh, Joni! She’s really a class by herself. Think back, back, back, back to before she was a self-anointed, gravel-voiced, pit-bull guardian of her own oddly humorless take on her institutionalized legacy, before her own bizarre insistence on some fanciful victimhood wherein she has been denied her due by an unlikely conspiracy of less-talented male sexists, even though she is probably the most beloved and respected singer/songwriter in the world! Yes, think back. Back to when Rolling Stone made a (farcical?) chart of everyone who’d slept with everyone in rock, and right in the center was the word “Joni.” Think way back to Joni’s first album, Song To A Seagull. It’s Joni’s most formal album, before she stretched her wings and the boundaries of songwriting itself to culminate in her masterpiece of emotional regurgitation, Blue. I admit, the yawning chasm of Joni’s contrived vibrato on Blue took some getting used to, but once acclimatized, it’s undeniably the zenith of searingly empathetic, rapturously melodic, masterfully poetic, unflinching behavioral observation. But—this just in—even though lines like “Acid, booze and ass/Needles, guns and grass/Lots of laughs/Lots of laughs” are incredibly masterful at being both caustic and poignant to the point of anguish, “Blue” is not really Joni’s weeper! For The Roses seems to take a more direct route to the tear ducts via songs like “Let The Wind Carry Me” (but God save us from that soprano sax!), but the lyrics haven’t aged as well as the music. To me, Joni’s true weeper is Song To A Seagull, hands down. The facile pop conceits that she abandoned later seem to actually help this LP. She struggles against her own innate craft to reveal her heart. But mostly it’s the eeriness of the production (by David Crosby yet!); to me (as demonstrated in the Searchers’ “Each Time”), spooky is definitely weepy-adjacent. Joni’s in a bell jar of reverb, and the acoustic guitar envelops you in a cold embrace like a passing cloud. The voice is schoolboy-pure and unaffected and, in its own way, equally chilling. The whole record reverberates with the first moment one realizes the meaning of loss and that all is certainly lost eventually, even as we grasp at it. The poetry is studied and occasionally puerile, even occasionally delving into outright post-hippie drivel, but her alliteration and the construct of ever more complex inner rhymes is glorious, and her hunger for words as a conduit to the soul is contagious. It’s like the spirit of Shirley Jackson made sonic. “Marcie” is as direct a tribute to Jackson’s portraits of small people caught in the sticky amber of constrained lives, with barely the power to dream. Joni’s pure tones almost save it from its inexorable will to the maudlin, but it’s the feeling that some mute, unconsolable ghost inhabits the song through the ouija of the sonic canvas that makes it ache. Even weepier is the creepy “Nathan La Franeer”: “Another man reached out his hand, another hand reached out for more/I filled it full of silver, and I left the fingers counting/And the sky goes on forever without meter maids and peace parades” becomes an epitaph for the lost hope of any true human connection (and the addition of the disquieting “banshee” siren that is like a doppler designed to chill the bone adds spectral icing). Sniffle! Even the upbeat songs like “Night In The City” are caught in an austere echo chamber of a foreigner, a child of innocence, trying to assimilate into a gaudy urban bustle that beckons but does not necessarily welcome. And then “Song To A Seagull” itself. I don’t know why, but when I first heard this song, I hated it. But now it’s one of my favorites. The sort of Bedouin/Hungarian chords, pedaling the Gregorian C#, the angular vaulting melody, so even after she leadenly belabors the “plastic flowers” and “concrete beaches” (i.e.,”fake plastic trees”—you can smell the cheese!), the last perfect line “But sandcastles crumble, and hunger is human, and humans are hungry for worlds they can’t share/My dreams with the seagulls cry, out of reach, out of cry” (sung in that glass-armonica soprano) make what was momentarily merely gooseflesh invite the tears that recognize that no one will ever be whole. Buffy Sainte-Marie’s version is great, too, with her frightening, I’ve-been-wronged vibrato sawing like fingers strumming teeth on a comb.

Sidelight to Joni is obviously fellow Canadian Neil Young. Just loads of weepers, and they need less explanation. I adore his first solo album, and “The Old Laughing Lady” certainly matches Joni for a place in the weep spook-a-thon. Lance and I were always sure “Last Trip To Tulsa” was about Neil’s bitter affair with Stephen Stills (we had good imaginations!), so the last line “I chopped down the palm tree, and it landed on its back” made that song into the ultimate noir revenge/weeper. Almost all of After The Gold Rush is a wonderland pool of tears; even the lopsided, backwoods sci-fi of “Flying Mother Nature’s silver seed to a new home in the sun” rings as an elegy to the loss of absolutely everything, and Neil’s fractured soprano, slithering out of that crooked mouth that looks like a crack in an eggshell, always sounds heartbroken no matter what he sings. “Birds,” in particular, is a sublime channel to your inner weepster. “The Needle And The Damage Done”? Well, I just need to hear the first chord, and I’m there. Of course, I married a few junkies, so I’m easy, and maybe that’s just me. “Sugar Mountain,” “Don’t Let It Bring You Down” and especially “A Man Needs A Maid”—the only time Neil set his inner Richard Harris free. But in the middle of the resplendent string crescendos is one of Neil’s most achingly woebegone-yet-clinical confessions: “Just someone to keep my house clean, fix my meals and go away/A maid/A man needs a maid.” Gets me every time. Yes, love hurts. And of course amongst his more recent inexcusable dross, his hippie jams and his lackluster “returns to form,” comes a gem every once in a while. I don’t know if it’s the over-used cinematic conceit of the home movies or the fact it was about AIDS (to which I have lost entire communities of friends and artists), but “Philadelphia” is Neil’s transcendent native gift at its most reductive, most direct: “City Of Brotherly Love/Place I call home/Don’t turn your back on me/I don’t want to be alone.” I’m already crying just thinking about it.

Instrumentals: I admit I know next to nothing about classical music, so my range of instrumentals that inevitably move me to tears is embarrassingly slender. But isn’t this getting a trifle too encyclopaediac anyway? So let’s leave it at this: the soundtrack to To Kill A Mockingbird. I remember when I was working with my friend Laurie Duchowney on her line of vintage patterns, and we’d put that LP on and both just well up and didn’t get a single thing done. The music so perfectly evokes the movie, which so perfectly evokes the sense of wonder and fear defining a childhood that can never be regained and is irrevocably moving into a past that is suddenly tragically foreign. Just looking at the picture of the broken toys and rubbish carefully saved as totemic treasures in that cigar box inevitably leads to an involuntary moan. “I was to be a ham … Thus began our longest journey together.” Snif! Then, of course, Samuel Barber’s Adagio For Strings, which, rube that I am, I first heard used in The Elephant Man. That composition snuggled so perfectly into the crook of my weepy virtual shoulder, I felt like it was part of me. And the association with David Lynch’s gorgeous visual lament of a film didn’t hurt either. Of course, when Oliver Stone viciously assaulted that divine association by co-opting the tune for his dreadful picture Platoon, I thought there should have been a general uprising of the weep-besotted or at least a lawsuit from the criminally weep-deprived. That Platoon association made my tear ducts as dry as Albinoni for years afterward. It just shows that the quality of weeping is strained; it can easily be perverted into a sere desert where no tear dare enter. Oliver, no! I also was once sitting in the messy living room of an incredibly intelligent and intense young man who had decided to dabble for a moment in the world known as “Homo,” and I was at the center of that rueful experiment. We shared so much ideologically and aesthetically, and I’ve always found someone who can drag my feeble intellect into a new mindscape incredibly sexy. He put on Mahler’s Symphony No. 5, which I must have heard when I saw Death In Venice years before, but somehow with this grubby artist holding my hand on his paint-splattered, threadbare futon, it took on a weepy urgency. Was this dalliance possible? No. In fact, unlike other queer boasts, I can only say I guess I eventually turned this guy straight! But I think the music transcends that specific introduction into an aural summoning of the sometimes pleasurable wave of emotions that overtake one, right before the crying scene. All this, and Death In Venice, too!

The warm alto of perversity: Karen Carpenter. No excursion into the reeking swamp of weepdom is complete without a nod to the queen of hyper-gorgeous perversity. Oh, how I love Karen. I remember when I was a DJ at Club 57 Irving Plaza, dutifully playing the latest 45s from the Sex Pistols, the Boys, the Adverts, the Cramps and the Damned, along with a few outré songs of the moment by Don And Dewey or Nervous Norvus, and I played “Calling Occupants.” There was a sudden tribal rush to the turntable station by red-faced Jersey thugs bristling with rage! I had actually managed to out-outrage the very crowd who touted their “punky” propensity for “outrage” as a badge of hipsterdom. That, and I now needed bodyguards when I was invited to DJ. I also sang (sort of) “Top Of The World” at the Mudd Club with a polka band backing me for one of Steve Masse’s inscrutable theme parties. Me and Karen go back, doncha know. But I actually have an unironic relationship with Karen. Though I didn’t really “go deep” with the stretched-out Crocker Bank commercial “We’ve Only Just Begun,” I sincerely appreciated the rarified craft of one Mr. Paul Williams. And then came a rash of unassailable Carpenters singles in the warmest alto I’d ever heard. She made Anne Murray sound like Babs after a rhinoplastic meltdown! And yet, there was a palpable subtext of unutterable tragedy drowning just under the surface of her voice that made even their most superficial bubble pap enjoyably melancholy. You could smell the pain. My favorite song of theirs will always be “Goodbye To Love” (one of their earliest singles not to go gold!). It was obvious that despite the almost depraved stiffness of Richard in his tighterthanthis Penney’s Towncraft velour, his stilted posture and his tormented hair, he had inadvertently “come out” in the lyrics as one who had earned his pathology through a life of being psychically battered by the emotional constraints of the very suburbia they parodied on the brilliant cover of “Now And Then.” Right from the top: “I’ll say goodbye to love/No one ever cared if I should live or die.” Ouchy! It was an exercise in sparkly transcendent dismay with a meandering melody as full of delightfully unexpected twists and turns as the Turtles’ “You Know What I Mean,” but it wasn’t their real weeper. No, that was “Superstar,” a song that is basically an idiotic groupie whine-fest. But the pain in that voice (and the exquisite Russell/Bramlett melody) made the hopeless longing for the impossible a journey through the watery vale of tears to the geyser apex of weepers! There have been many aspirant OKCs (Other Karen Carpenters); Chrissie Hyde’s beautiful “Birds Of Paradise” comes to mind. But Karen will always be the Queen Of Cry!

Loose ends: Wow, there’s so much I didn’t get around to. Dusty: ooooodles of stuff, especially two Newman greats (“I Don’t Want To Hear It Anymore” and “I’ve Been Wrong Before,” although I find Mark Eitzel’s version of “No Easy Way Down” to be more moving and less rushed). How could I forget John Phillips’ “Look Through My Window”; just try to get through the post-break-up scare-aoke contest when you get to these lines: “See the people scurrying by with someone to meet, some place to go.” And he’s given stiff competition by his own “Old Time Movie.” Rufus Wainwright’s “Going To A Town” and “Dinner At Eight.” Classics: “Smoke Gets In Your Eyes” (I prefer the Platters’ version), Irving Berlin’s “What’ll I Do” (perhaps the template for all perfect weepers), Elvis Costello’s criminally underrated “Home Truth.” Loads of Kirsty MacColl. And my own humble attempts to crack the genre: “Now I Understand,” “I Had My Chance” (during the recording of which my super engineer Earle Mankey got very impatient: “What’s happening out there?” I heard through the cans. Well, I was crying. At least my weepers work on me!), my duet with Rufus Wainwright on “Scarecrow,” my collaboration with Ann Magnuson on “Whatever Happened To New York?” (a brazen attempt to repurpose ABBA’s “Like An Angel Passing Through My Room” and with yet another generous vocal contribution by Mr. Wainwright) and perhaps my favorite of my own weepers, Timur Bekbosunov’s interpretation of my “What I Meant To Say,” an ode to dear dead Bradly. Timur’s production makes a dense shadowy fog of artful feedback through which the lost heart will never find its way home. Oh, kids, I’m barely started. But now you know the game: Get out there and amaze your friends with your own lists of weepers. There’s plenty of tears to go round!