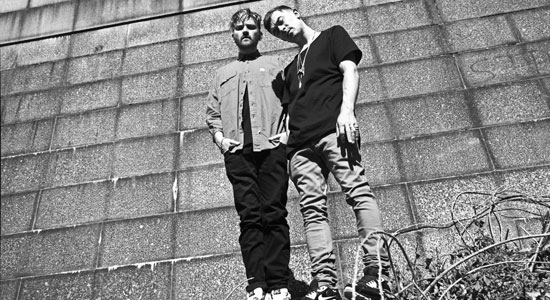

There were shimmering moments on 2009’s excellent A Brief History Of Love wherein the Big Pink appeared poised to sneak the adventurous, clever early-’80s synthpop of the New Romantics back into relevance beneath a cloak of Phil Spector (by way of Jesus And Mary Chain) noise. The vision, alas, remained a bit murky, lost in Psychocandy-lite squalls, never quite cohering into a fully realized whole. On the band’s beguiling sophomore effort Future This (4AD), however, the Brit electro-gaze duo lives up to its considerable promise with 10 sleek tour-de-force anthems: Imagine a Y-chromosome-fronted Britpop version of Tegan And Sara or maybe a grittier, wised-up a-ha backed by a supergroup comprised of Kevin Shields, Bernard Sumner and Jam Master Jay, and you’ll be in the right neighborhood. “Lose Your Mind” could be a Simple Minds b-side circa “Sanctify Yourself.” In short, a fantastic, uplifting listening experience. MAGNET recently spoke to the Big Pink’s Milo Cordell about how he and ex-Alec Empire guitarist Robbie Furze went about creating a fearless genre-bending opus that is sure to be one of the most consequential records of 2012. Cordell and Furze will also be guest editing magnetmagazine.com all week.

“Give It Up” (download):

MAGNET: Future This is a much more streamlined effort than A Brief History Of Love. Was this intentional?

Cordell: Totally. The first record captured a moment between sounds. We were very much into wall of noise and guitar and drone-based music and then halfway through writing the songs we discovered the potential of programming beats. So A Brief History Of Love is a bit of a mismatched collection of songs written over a period of a couple years. Future This is much more focused; we had a lot more time to step back out of matrix and have a look at ourselves while we were writing it. And after touring the last record for so long we knew we wanted the next one to be a lot more energetic, a lot more upbeat.

Since you mention the upbeat vibe. There was a lot of darkness on A Brief History Of Love, while Future This is ebullient, even triumphant.

A Brief History Of Love was a personal record written during a very dark time in both our lives. Obviously that time passed and we were having the time of our lives—going on tour, being in a band—while still playing songs that were essentially quite dark. In the middle of this we started to think, “It would be so great if we were going out each night playing songs that weren’t about such a negative period of our lives; if we were going out playing good, positive, pop songs.” That was where the backbone of Future This started.

Did album opener “Stay Gold” come early in the writing process? It is a real tone setter.

Yeah, I think “Stay Gold” was the first track we wrote for this record. It’s kind of the bridge between this record and A Brief History Of Love. It has one foot in the sound of first record, but has the positivity and upbeat feel of the new one.

Future This is also a much less guitar-driven record.

We just wanted to get ourselves out of our comfort zone—that was the main objective. Robbie didn’t pick up his guitar for four months. We had to ask ourselves, “Well, if we’re not going to do that, what are we going to do?” So we started basing tracks around samples; Laurie Anderson on “Hit The Ground,” for example, and Ann Peebles on “Give It Up.” That was a new production style for us and we really enjoyed the process. You end up at places you never would have otherwise arrived had it not been for that sample, and it was a really liberating experience, musically.

One thing it will definitely liberate you from is the shoegaze label.

You know, we love shoegaze music, but we always disagreed with that description of our band. I think there are better ways to describe us and there are better shoegaze bands than us. Shoegaze was just one element of our sound. On Future This we wanted to put across the other elements of the music we love, whether it be hip hop or certain types of dance hall or just pop music, really.

The elements are different but there seems to be a real continuity to the compositional approach.

It’s true. The same raw elements of production are still there. What we used to do was make the racket, record it, then go back and sample ourselves, whereas this time we decided to sample other people and let that dictate the track. We really upped our production game. Before we were relying on distortion and these walls of sound to hit on choruses and certain parts. It was kind of rigid; the beats were much more powerhouse industrial beats. It didn’t really have any kind of swing or sway at all. We wanted Future This to be a lot more fluid. We wanted it to have a bit of a hip-hop bounce as well as that shoegaze indie head swing. Basically, if the record makes people shake their asses and their heads at same time, that would be good.

The Big Pink blew up as a sort of hip London club phenomenon. Now you’re signed to 4AD, which has this indie-rock cache. I’m curious if you’ve seen any change in the crowds at your shows as the band has grown and evolved.

Well, at the beginning it was definitely all scenester kids, but that quickly changed once we started getting played on the radio and had some mainstream success. Now we’ll meet 60-year-olds guys at shows who read about us in some magazine. Then there’s the My Bloody Valentine/shoegaze contingent and the 16-year-old girls who loved “Dominoes.” It’s very diverse now, all different types. Which is great.

I recall reading that you personally adapted to the stage slowly. You’ve been touring for awhile now. Has that abated?

Mostly. For me, to begin with, it was quite tough. I don’t play an instrument. Essentially, I’m a musician only because I say I am. [Laughs] I can’t play guitar, I can’t play music by hearing it. I’m good at sounds and how songs should flow, but when it comes to actual musical instruments, I’m not the best. So I’m always aware of the struggle it will be to learn to present a song live. My nerves’ll always be there, I think. But the shows have just been getting better and better.

How so?

We’ve got a completely different setup now. Toward the end of touring the last album it got really repetitive. We became a rock band, which is the last thing we ever wanted to become. So we stripped everything away and brought in computer setups that enable us to perform the songs as intended, live, without a tape machine. All samples are dropped live. We can loop stuff up, we can change tempo, we can change pitch. Everything is constantly mutating onstage, which for us is really exciting. We’re not stuck in any kind of rigid four-instrument band structure. When you work with synthesizers and computers you can bring in the sound of church bells or jazz organ or sub-bass from a ’90s drum ‘n’ bass track. You can do whatever you want.

Both you and Robbie have roots in more antagonistic electronic music. Do you miss that aggression at all now that you’re so fully immersed in big hooks and epic choruses?

Not really. The more vitriolic noise elements we enjoyed from that kind of music is still there. And if we can bring in elements of Cabaret Voltaire or Atari Teenage Riot into our pop songs, however slightly, whether in a drum break or feedback drone, and push that into the mainstream psyche, that’s quite a perverse turn-on for us.

Have you received any feedback from Alec Empire?

Yeah, he tweeted something about our New Order cover band the other day. I tweeted back that I’d never owned a New Order record in my life.

Did he respond?

He came back with something particularly German I can’t remember right now. It is funny, though, how you can end up being compared to bands you never really listened to and had no intention of imitating.

Does that relate at all to what you’re trying to get across with the title of this record?

I collect words and slogans and sentences, write them down. The first two words at the beginning of one of my notebooks were “future this.” It just stuck and it seemed an apt title for a new beginning for us. Future This is a bit like, “Fuck you.” It is our statement to wipe clear a new space for ourselves.

—Shawn Macomber