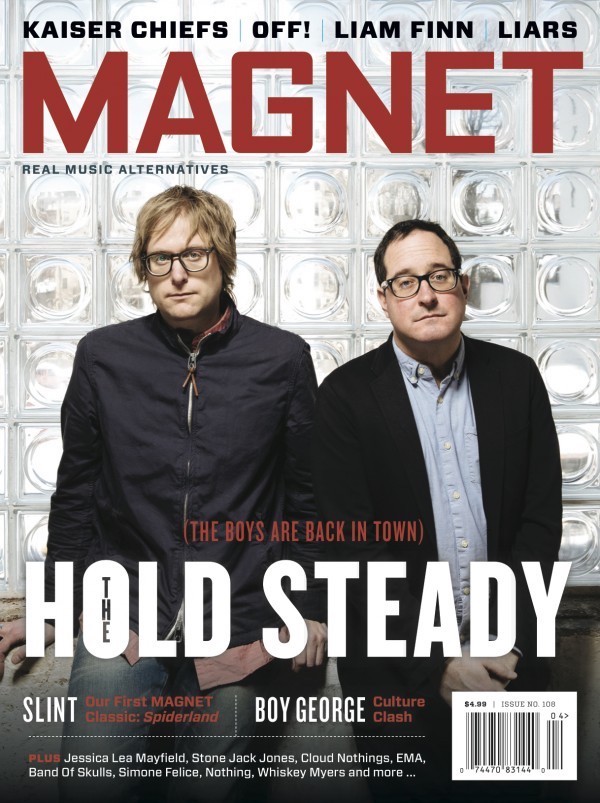

To celebrate our return to publishing the print version of MAGNET three years ago, we will be posting classic cover stories from that time all week. Enjoy.

After a decade of cheap beer, positive jams and killer parties, there’s blood on the carpet, mud on the mattress. MAGNET goes to Brooklandia to watch the Hold Steady sleep it off and wake up with that American sadness.

By Jonathan Valania

Photo by Gene Smirnov

When Hold Steady frontman Craig Finn was growing up in suburban Minneapolis in the shag-carpeted ’70s, there was nothing musical about the Finn family. Nothing at all. Nobody played an instrument. Nobody played records on the stereo. They did not even sing show tunes on long car rides.

But when Finn was eight years old, Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham choked to death on his own vomit, and that’s when a young boy discovered the awesome, mood-altering, life-changing power of rock ‘n’ roll. Up until this point, he’d thought of rock ‘n’ roll as nothing more than the interstitial music between the zany capers and wacky hijinks on The Monkees and The Bay City Rollers Show. But judging by the trail of tears running down the apple-hued cheeks of his babysitter—a pretty neighborhood teen he had a secret crush on—this was an Important Cultural Moment, right up there with the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the Kennedy assassination. His babysitter made him listen to Led Zeppelin A-Z that day, and there would be no turning back. One day, he vowed, with God as his witness, he would make pretty girls cry when he died. This remains a work in progress.

This year, Finn turns 43, and the Hold Steady turns 10. (Technically 11, but who’s counting?) The kids at their shows now have kids of their own, as the song goes. On March 25, the Hold Steady released Teeth Dreams, its sixth studio album. (The band also boasts six EPs and a live LP.) If the Hold Steady was the Replacements, this would be its Don’t Tell A Soul.

It’s been four years since the Hold Steady released an album, which is something like 16 in rock ‘n’ roll years. Entire presidencies, college sports careers and World Wars come and go in the span of four years. In that time, the Hold Steady came closer to ceasing to exist than anyone in the band cares to admit out loud. Ego, exhaustion, addiction and communication breakdown—the great hunger-makers of rock ‘n’ roll’s infamously insatiable appetite for self-destruction—have left their scars, as they invariably do to bands around the six-album mark. Which only goes to show that there is always a crack where the darkness gets in, and even a critically acclaimed band that has waved the flag of positivity highly and mightily is not immune to private despair.

Fortunately, the members, all at or nearing 40-something, were mature and self-aware enough to recognize the warning signs and course-correct before it was too late. So, they took some time off. Finn started working on a novel, then flew to Austin and recorded a well-received solo album, which he toured on for a year. Guitarist/primary songwriter Tad Kubler got clean. Drummer Bobby Drake bought a bar in Brooklyn with Spoon’s Rob Pope. Keyboardist Franz Nicolay took his leave and was replaced by noted six-string shredder Steve Selvidge. (The latter is the son of late, great folk singer/recordist/indie-label pioneer Sid Selvidge, a pillar of the Memphis music scene for five decades who will be remembered for, if nothing else, having the sheer balls to release Alex Chilton’s Like Flies On Sherbert, one of rock ‘n’ roll’s all-time great hot messes.) They got new management, a new label, a new producer and a whole new attitude—more heart, less cowbell. And unto the world a new Hold Steady album was born.

***

It’s 3 p.m. on a yet another colder-than-a-witch’s-tit late-winter afternoon in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Craig Finn is nursing a seltzer and lime at a back table at Lake Street Bar, an old-man dive short on old men and long on beardo Brooklandians getting a head start on tonight. Finn asked to meet here because he knows the owner—Hold Steady drummer Bobby Drake, who is presently restocking the bar in preparation for the coming happy-hour onslaught—and, as the song goes, the drinks are cheap and they leave you alone.

He’s a little bummed at the moment. His friend Oscar Isaac didn’t get an Academy Award nomination for his indelible portrayal of Llewyn Davis in the latest Coen brothers film. “I think he got screwed,” says Finn emphatically. “He was mind-blowing.”

The first thing you notice about Finn when you get up close and personal is the kind, clear eyes hidden behind his trademark Clark Kent spectacles. Soft-spoken and courteous, dressed in a blue V-neck sweater over a crisp white oxford, his hairline making a slow northward retreat, Finn looks more like the guy who would do your taxes than the fierce, suds-fueled, battle-hardened, 21st-century defender of the rock ‘n’ roll faith in his press clips. He knows this, of course. He gets it all the time. And he made his peace with it a long time ago. But that doesn’t mean that, deep down, it doesn’t still sting a little. Matador Records honcho Gerard Cosloy famously dismissed the Hold Steady as “later-period Soul Asylum fronted by Charles Nelson Reilly.”

“I remember when that came out, I was like, ‘If I read that, I’d probably want to go see that band,’” says Finn when I ask if he cares to respond. “Honestly, though, I was also disappointed because it wasn’t meant to be complimentary, and the dude’s label has put out some of my favorite bands. But you’ve got to let some of this roll.”

Finn is too nice of a guy to return fire, so I’ll do it for him. Craig Finn—who, come to think of it, doesn’t really look all that different than Gerard Cosloy—has something that the Cos, for all his vast reserves of hipness and uncanny knack for recognizing what’s next before everyone else, will never have: the gift of the common touch. Like the Boss, from whom he is a clear descendant, Finn has never pulled a shift on the line, he doesn’t play beer-league softball with the boys on Saturday afternoons, his hands are soft, and he votes straight Democrat. Hell, he read Infinite Jest. Twice. But, also like the Boss, he has an unshakeable belief in the transcendental power of a shit-hot bar band to set the working man free on a Friday night—if only until last call—and is more than willing, night after night, to shed the requisite blood, sweat and beers it takes to git ’er done.

So, word to Mr. Cosloy: Next time they ask you about Charlemagne, be polite and say something vague.

Back in 2003, when Craig Finn and fellow Lifter Puller alum/Minneapolitan-turned-Brooklandian Tad Kubler assembled a Paul Shaffer-style house band to pound out Bowie, Cheap Trick and AC/DC covers between sketches by a short-lived, Upright Citizens Brigade-derived improv comedy troupe called Mr. Ass, they had no greater ambition than to drink beer and, like, really fucking kill it on “Back In Black.” Exhausted and dispirited after spending the better part of the last decade in Lifter Puller trying to smash through the glass ceiling of local celebrity back in the Twin Cities, Finn had more or less called off the search for the holy grail of rock stardom. It was supposed to be fun, but by the end of Lifter Puller, it was anything but.

However, this really-fucking-killing-it-on-“Back In Black” business? That was fun. A lot of fun. So, even when Mr. Ass went away after two or three shows, the band kept going. It even started writing songs, with big muscular AOR riffs and dense, cinematic word clouds for lyrics. Even in his Lifter Puller days, Finn was a fierce and formidable storyteller, able to connect the dots of human foibles with an eagle eye for micro-details, a master of the withering aside with a gift for transmuting public experience into private mythology, his barbed-wire snarl spitting out ultra-vivid vignettes of debauchery and grace at an amphetamine pace. But when wedded to this new group’s propensity for unironic, unapologetically anthemic hard-rock crunch—more Zep, less Wire—Finn’s noirish, photorealistic rants sounded like the Gospel according to Charles Bukowski. There were recurring characters awash in American sadness—Charlemagne, Gideon, Hallelujah, Hard Corey—scratching around in the dark of some post-kegger purgatory for dope, sex and transcendence … or at least one last cigarette before they slip into unconsciousness.

Hmmm … maybe they were onto something.

A show was booked at Northsix, which meant they needed a name. They met for breakfast to discuss it. Finn wanted to take a phrase from “Stay Positive,” one of the first songs they ever wrote:

All the sniffling indie kids: hold steady

And all you clustered-up clever kids: hold steady

And I got bored when I didn’t have a band

And so I started a band, man

We’re gonna start it with a positive jam

Hold steady

All it needed was the definite article the, and behold: An action becomes a thing. A many-splendored thing. A second chance at glory. A band on a last-chance power drive. All were agreed: The Hold Steady it is. So, they had songs and they had a name; now all they needed was a crowd. This being the days when dance-punk was ascendant, they weren’t so sure how it would play with the cool kids. I mean, they liked it; they thought it was good—maybe even great if they went all in—but what did they know about New York? They were from the Midwest.

“I knew it was going to be an affront to some people, but there was a lot more people at the first Hold Steady show than I thought there was going to be,” says Finn. “I thought it was 100, but maybe it was only 60. A fair amount of them were people I didn’t know. That’s the thing—like right away, there was people I didn’t know.” One hundred people—or for that matter 60 people—show up to see the first gig of a band that didn’t even have a name before breakfast this morning? Yes, they were definitely onto something. F. Scott Fitzgerald said there are no second acts in American lives, but that’s because F. Scott Fitzgerald never heard Almost Killed Me.

***

In the beginning, Craig Finn was born in Boston; but in grade school, he moved to Minneapolis, where lived until 2000, when he moved to Brooklyn. He’s been there ever since, but if anyone asks, he’s from Minneapolis. His dad was a tech guy for a big accounting firm, and his mother was a housewife. He has no brothers and one sister. She is five years younger than him and still lives in Minneapolis, as does his dad. His mother is deceased.

The first band he fell hard for was the Ramones. “I didn’t even know they were punk rock,” says Finn. “I just thought they were a less successful rock band that I heard and I liked.” By junior high, he started figuring it out. His friends had older brothers. Mix tapes were traded. Rock elder wisdom was dispensed. One day he saw a flyer on a telephone poll advertising a TSOL show at the local VFW or some such. “Where is that and how do I get to that?” he asked himself. After asking around, turns out you could get there from here, and he started going to all-ages punk shows all the time. One night, when he was all of 13, someone from the Descendents asked Finn and his buddies if they knew a girl who would give him a blowjob. “If we knew that, why would we be here with you?” Finn told him, displaying a mastery of the withering retort well beyond his years.

“We weren’t even close to knowing somebody like that,” he says now.

Growing up in the suburbs, you had to take a couple buses to get to the cool record store in town. It was not easy; you had to want it. This was pre-Cobain. You couldn’t just go to the mall. Every Saturday, Finn and his buddies would get on the bus. The plan was simple, but very effective. Everyone would buy one album, and then they’d go home and everyone would make a cassette tape of everyone else’s purchase. So, for the price of, say, R.E.M.’s Reckoning, you also got the first Violent Femmes record, the Replacements’ Let It Be and Hüsker Dü’s Zen Arcade.

The Replacements. Was that an important band for you?

Finn: The most. I heard about them from this guy who said his older sister knew them. I didn’t know if that was even true, but I went and got Hootenanny and couldn’t believe that this was happening near me. I had never seen anyone in my life that looked like Steven Tyler or knew anyone like that, but I knew dudes who looked like the Replacements. I knew where to find them, you know? So, it was sort of more believable.

Did they reinforce the notion that you don’t have to go to a stadium to see a rock show? That you can go to an all-ages show in a basement or rec hall and be three feet away from them?

Finn: And we would. I remember being—and it’s so funny, because you go to shows now and you’re always trying to time it to see the band you want to see—but it would be like “doors open at 4 p.m.,” so we have to get there at 3:15 at the latest. You know, if I missed 10 minutes of the opener I would be bummed. But every band was good. Or at least always worth it. But I had really weird ideas about what it meant to play in a band at that level, like I couldn’t do the math somehow. Like, “Oh, they’re probably making $40.” I didn’t even really know about touring. I was thinking, “The Descendents are coming—they must be flying in for every show.” I mean, we were having conversations at one point about going to the Amfac, which was the nicest hotel downtown at the time, to see if we could get Black Flag’s autograph.

Now what about Hüsker Dü? Not as important to you?

Finn: Very important. It’s funny—they kinda did not appear punk enough to me as a young kid. Bob Mould was kind of chunkier, Grant Hart had the long hair and bare feet, and Greg Norton had the handlebar mustache and short shorts. I was like, “What is this?” I mean, they are my second favorite band. Soul Asylum was the third; they were awesome and almost combined the two.

Finn and his friends started a band called, regrettably, No Pun Intended—or N.P.I., as was the style of the day. It was slow going at first. It took them weeks to get the hang of “Should I Stay Or Should I Go,” which might as well be called “Punk Rock For Dummies.” Finn did not yet have the cojones to pull off lead singer; that job fell to the “cool, good-looking guy that could actually sing.” Instead, he played guitar, barely. And, more importantly, he started writing songs.

N.P.I. lasted four years. Mainly covers. They broke up when they all graduated and Finn left for Boston College. BC was a much different scene than the Twin Cities, fairly conservative. He had a few friends who liked music, but he invariably wound up going to hardcore shows by himself. So, Finn hunkered down and did the college-dude thing: girls, beer, classes. But the last semester of his senior year, he formed a band in the Dinosaur Jr/Buffalo Tom mold, as was the style of the day. It was called Sweetest Day, which is sort of the Canadian Valentine’s Day. Finn switched off on bass and guitar, and sang with a lazy, stonery J Mascis-style yowl, as was also the style of the day. The band got good enough to play the Rat. Suddenly, people reacted differently to him. He felt cool. And it felt good.

After college, Finn moved back Minneapolis, where rent was cheap and he “knew a lot of people who worked at bars and played in bands, and stuff like that.” He got an apartment with one of his fellow BC alumnae, a guy named Dave Gerlach. They started a band and called it Lifter Puller—a pun on a Twin Cities bong euphemism. A bong gets you high, so it’s a lifter. And the person who sucks the smoke out of a bong is a puller. Doing bongs equals pulling lifters. Hence, Lifter Puller.

He changed up his vocal style. Less Mascis, more Mark E. Smith: acerbic, talky, cutting. Partly it was a function of singing out of an amp at rehearsals and trying to get over the band. Partly it was a function the clipped, percussive, hard-consonant lyrics he was writing. Partly it was a function of him having figured out a long time ago that he was neither a pretty boy nor a crooner.

Lifter Puller put out three albums over the course of six years. More importantly, for our purposes here today, one Tad Kubler, straight outta Janesville, Wisc. (pop. 63,588), arrives in town at roughly the same moment that Lifter Puller was in the market for a bassist. A guitarist by trade, Kubler was willing to take a bullet for the team.

In 2000, Lifter Puller called it a career and Finn took off for New York City. “I was married at the time,” he says, “and it kind of felt like after the band broke up in Minneapolis, it was either like, ‘Buy a house and have a kid,’ or else double down on rock ‘n’ roll. And I knew Minneapolis had gotten a little small, and there was also a bit of a drinking culture there that I saw that was maybe going to go down a … there was a lot of just sitting on a barstool going on there. That’s fine, but I just sort of was like, ‘Maybe this is the time.’ I moved to New York about three weeks after Lifter Puller played their last show. It was the Internet Age, so I got a job quickly working for a start-up that did webcasting of concerts.”

***

It’s a couple hours prior to my audience with Craig Finn, and I’m sitting in Tad Kubler’s Lilliputian Greenpoint apartment, which he shares with nine-year-old daughter Murphy and a cat named Mouse. It has been pointed out on Hold Steady message boards that the blonde and bespectacled Kubler looks like the less googly-eyed brother of The Office co-creator Stephen Merchant. When Kubler was seven, Cheap Trick’s manager at the time lived across the street in Janesville, and one day he got to meet Rick Nielsen. There would be no turning back.

After bumming around Madison for a while, he made his way to the Twin Cities at precisely the moment that Lifter Puller was in the market for a bass player. When LP called it a career in 2000, he headed to L.A. to pursue portrait photography before ricocheting back east until he wound up in New York City, where he found work shooting the likes of Leonard Cohen, Gregg Allman and Arctic Monkeys for Rolling Stone. Eventually the Hold Steady took over as his primary passion/creative outlet, then, a couple years after that, his day job. Up until a few years ago, he was Neko Case’s boyfriend.

Alcohol, like sex, dope and God, is one of rock n’ roll’s great force multipliers (see: the Replacements). It’s also the great undoing of the many languishing in the Dionysian precincts of rock stardom (see: the Replacements). If nothing else, the Hold Steady is the world’s greatest bar band. In the early days, the Hold Steady played loaded for bear. On a good night—and depending on how much they and you had to drink—they didn’t just rock; they summoned up sweaty Springsteen-ian salvation. Rock ‘n’ roll was their church, and beer was sacrament. The problem with rock ‘n’ roll as religion is that the only way to get to heaven is to die. Back in 2008, Kubler almost got there.

For a while there, he was drinking a bottle of whiskey a day, if for no other reason than he could. “I’m one of those guys with that metabolism where I can just do more than most and it doesn’t have much effect,” he says. “I could drink almost a liter of whiskey and get onstage and play a show.”

Until he couldn’t. By 2008, Kubler had drank himself into acute pancreatitis, which leads to organ failure, necrosis, infected necrosis, pseudocyst and abscess. “Basically, your pancreas stops working and then tries to kill everything else in your abdomen,” says Kubler. “It’s also very painful. It feels like somebody smashed a windshield and you swallowed a handful of broken glass and washed it down with a glass of orange juice. And then the pain grows—it gets to be so bad you are vomiting and then passing out because it’s so painful. The thing about pancreatitis is there is no treatment for it; you just have to stop using it. No food, no water. Two weeks. In intensive care for five days, and then a regular room, on morphine and Dilaudid the whole time.

“So, you get out of the hospital and you can’t drink anymore, and you’re like, ‘I know what I’m gonna do—I’m gonna go pro (with heroin). I would have bouts where I would try to get cleaned up and would wind up drinking again. When we were working on Heaven Is Whenever, I wound up in the hospital again. And they were like, ‘The fuck you doing? We told you this was going to happen.’”

Being in the Hold Steady but not allowed to drink, on pain of death, is like running a brothel with your wife. “Being on a bus with people who are drinking and partying, I kind of built up a wall,” says Kubler. “I knew none of those guys would go there, so it was like my thing. It feels incredible for a while, and then after a while you’re just maintaining, and then you’re fucked.”

By 2010, around the time the band was finishing up Heaven Is Whenever, Kubler had had enough. “I was like, ‘Fuck this. I don’t want to do this any more,’” he says. “OD scares? Sure. Because I used alone, there were times I would just wake up a few hours later and be like, ‘Fuck!’ And you make all kinds of deals with yourself. I don’t want to turn this into an NA meeting, but a lot of my using was resentment, and resentment, as they say, is like drinking a bottle of poison and expecting the person you resent to die. Here I am in a band that’s about partying and I can’t do that anymore, so I’m just going to hide.”

There were other resentments, too. Kubler writes all the music, but Finn gets all the credit. That’s not necessarily Finn’s fault—he is the frontman, lyricist and the face of the band (the glasses, the smirk, that hairline), and it comes with the territory.

“When you are the lead singer of the band, there’s more scrutiny, and you tend to be the focal point of a lot of derision and animosity and criticism—and that’s tough—but you are also the focal point for a lot of the praise,” Kubler says, carefully choosing his words so as not to sound bitter or needy. “I’m sure it’s hard to deflect that. To say, ‘Wait, you are this, but it’s actually that.’ To be like … it’s all happening so quickly, you can’t really stop and be like, ‘This is what really happened.’ So, you just let it wash over you and you let it be that.”

Kubler had gotten clean and sober in the nick of time, but it may have been too late to save his relationship with Finn. The bottle and the damage done. The seeds of doubt had been planted.

“I’m sure by that point he was thinking, ‘This guy could not even be around in a year,’” says Kubler. “I’m sure he was worried about me as a friend, but also worried about me as a business partner and a songwriting partner. I don’t blame him for doing a solo album. The only problem with it is he didn’t do a very good job of communicating what his plans were, so it went from taking three months off to taking a year and a half off. In that time, me and Bobby and Galen (Polivka, bassist) and Steve would get together and work on new material. So, by the time he gets back, we have 24 songs with no lyrics, and at that point, after touring for a year, he’s emotionally spent, creatively spent, and now he’s got an overwhelming amount of material that he’s got to come up with words for, and he’s not super-inspired. That’s why it took another year to get the album done. When he got back, I could tell he just wasn’t clicking. It felt like Heaven Is Whenever, when we weren’t clicking and we should have just shelved that and come back to it. But all that had to happen for us to get to where we are now.”

Where they are right now is backstage at the Williamsburg Music Hall. It’s a couple weeks later, and the Hold Steady is celebrating its 10th anniversary (11th, if you’re actually counting) at the club where the band played its first show. (Back then it was called Northsix.) That’s the problem with starting a band in Brooklandia. Sooner or later, your creation myth will be gentrified. The show is way sold out, and the club is hot and heaving. Many cups runneth over. The bartenders pull on the taps like a Texas prison warden flipping the switch on the electric chair: over and over and over again.

Outside its dressing room, the Hold Steady lines up in the narrow hallway leading to the stage and, as per band ritual, high-five each other the way baseball players shake hands at the end of a game. Except this game has just begun, and it’s definitely going into extra innings.

The band takes the stage to the strains of the Velvet Underground’s “We’re Gonna Have A Real Good Time Together.” Moments before the Hold Steady launches into “Stay Positive,” Finn straps on his guitar, grabs the mic and makes a declaration. “This is for anyone here who saw us at Northsix and anyone who wakes up and says, ‘I’m not old—I’m old fucking school!’” Crowd goes nuts.

And then he takes off his guitar, the instrument which, it is well known, he does not play so much play as wield like a shield. “My New Year’s resolution is to stop playing fake guitar,” he says. “It’s 2014—let’s stop lying to each other.” The band lurches into the rutting bump and grind of “Stay Positive” before segueing right into the Stooge-ian electric mainline of “The Swish.” Finn flops around the stage, alternately poking his finger in the crowd’s chest in that hey-you-kids-get-off-my-lawn way of his, or frugging comically like Igor doing the time warp again. The crowd goes ballistic. Beer showers down from the balconies, baptizing a sea of pumping fists in warm PBR.

Two hours and two encores later, they end with the last song from their first album, “Killer Parties.” It’s the one that starts with that line that goes, “If they ask about Charlemagne, be polite and say something vague.”