The Vulgar Boatmen are an archetypal cult band. Those of us who love them really, really love them, but the three albums the Indiana/Florida band released between 1989 and 1995 never reached a wide audience. So, the reissue of debut You And Your Sister, bolstered by a pair of new remixes and three previously unreleased tracks, is a gift. Dale Lawrence and Robert Ray wrote strummy, propulsive tunes that could recall Good Earth-era Feelies, the Velvet Underground or Stax/Volt soul. The band will be guest editing magnetmagazine.com all week. Read our new Q&A with Lawrence.

Lawrence: In the mid-’90s, my then girlfriend and I spent a week’s vacation in southern Louisiana, mostly the area 30 miles any direction from Lafayette: rural Cajun country. Previous visits to New Orleans (by any measure, a pretty exotic place) had in no way prepared me for the flat-out weirdness of Eunice, Mamou, Opelousas, Breaux Bridge. As a couple of modern Americans who devoted a pretty hefty percentage of their free time to seeking out regional idiosyncrasies, less-than-obvious diversions, we were in Paradise. Here was an entire section of the U.S. that had seemingly slipped through the cracks, whose customs, food, language, music seemed not to refer to anything outside itself, certainly not to any officially sanctioned (corporate) version of What To Do. Music especially: Every weekend, Louisianans en masse get dressed up and head to ancient dancehalls (some of them little more than barns located “way out in the country”), where they dance all night to local Cajun and zydeco bands. Radio stations (some operated in French) cater to these tastes. Local recording studios and record labels have thrived for decades essentially selling records to one third of one state.

As much fun as it was to experience the dances (and bush-track horse races and bayous and cockfights and Cajun restaurants), the biggest kick, in a way, was just being there, immersed in a life made up of connections between all these strange and beautiful component parts, a life around the corner, truly Somewhere Else. Occasionally it resembled time travel, but mostly it seemed to offer exciting proof that modern life (the present) could be different, could be transcended, that Time-Warner could be made irrelevant. It felt like a chance to exist fully in the present, partly because that present had not been wrenched from its own history.

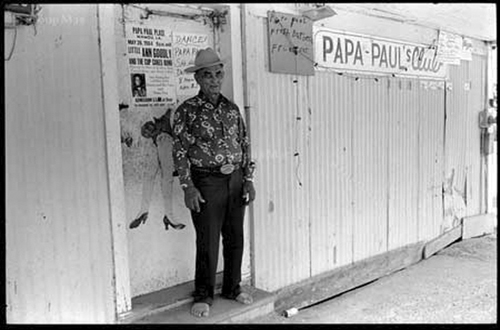

If I had to pick a single highpoint among highpoints, it would be the night we visited Papa Paul’s Club in Mamou. It was my first zydeco dance and the mark by which I measured all the ones that followed. The exterior, like most Louisiana halls, was unassuming, might have housed any sort of business or none at all. Inside, everything—dance floor, bar, tables—was made of wood, and the entire place was vibrating, quite literally: The plank dance floor bounced, and while it was occupied, there was not an inch of floor in the room that wasn’t noticeably shaking. We were the only white people there, insuring my gal never lacked for dance partners. It was our introduction to several singular Louisana dancehall customs. For instance, no one ever applauded the band (it was clearly a dance, not a concert), and at the end of every song, all dancers returned to their tables, only to jump up again 30 seconds later, when the next song began. The band, already cooking when we walked in, turned out to be Beau Jocque & The Zydeco Hi-Rollers, legends in the zydeco universe (who we, of course, had never heard of). The music was riff-based, pulsing, relentless, made me think of some alternate-universe James Brown. And if all of that weren’t enough, when we returned the next afternoon to take pictures, Papa Paul himself was there (he lived on the premises) and invited us in. Slight of frame, in his 70s, the fact that he spoke only French did not stop him from giving us a tour of his home and letting us help feed his chickens.