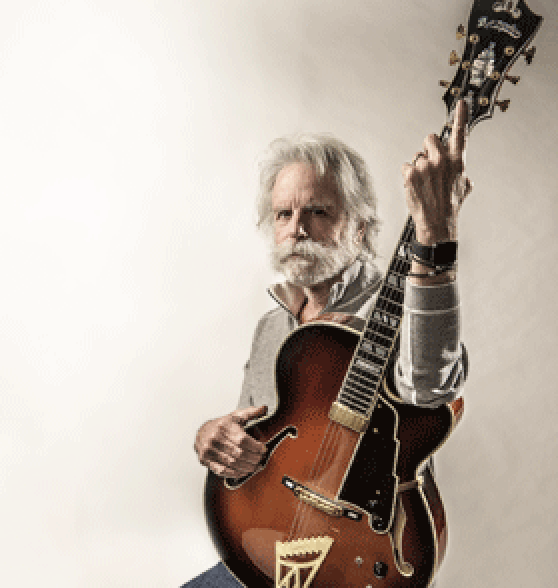

Not since 1978 has singer/songwriter/guitarist Bob Weir released a solo album with his name alone above the title. That’s until the new, country-ish Blue Mountain. Yet no one could fault him for laziness, as this founding member of the Grateful Dead has—since that psychedelic San Francisco treat disbanded in 1995 after Jerry Garcia’s death—worked and recorded as Bobby And The Midnites, Kingfish, RatDog, Furthur and in duo settings with Rob Wasserman. Famously in reunion with the surviving Dead, he played 2015’s Fare Thee Well goodbyes and continued to tour (yeah, we know) with John Mayer as Dead & Company in 2016. Starting with this year’s release of multi-artist tribute Day Of The Dead, Weir has thrown in his lot with the National, whose membership curated that boxed set and play all over Blue Mountain with other cats like Craig Finn, Josh Kaufman and Josh Ritter. Then there’s that beard …

Your last 12-16 months have been auspicious and relatively unceasing. Are you someone who needs to be moving nonstop because you’re easily bored, because there’s so much music in you that you must get it out, or do you owe somebody money?

Actually, it’s a combination of all of them. I’m not positive how much I do owe, but at this point, I’m doing OK. A lot of great stuff comes my way in terms of making music, and it’s hard to say no. That’s what I’m here for. Yeah, I’m easily bored, but I’m also as lazy as the next guy. For some reason, I’m staying busy.

Are you a man who compartmentalizes things, ideas and sounds, or do they intermingle among projects?

You know, that’s a good question. I have to wonder about that. This record for instance—I don’t think it sounds much like what I’ve done in the past, and you can put that down to people I was working and writing with. Then again, I did some of the writing myself. It’s not like other stuff, that it presented itself as an entity without a border or past connection. It wasn’t meant to be a part of what has come before for me.

You say entity without past, and there’s Josh Kaufman, Josh Ritter, Craig Finn and the guys from the National. Did they bring this to you, this country ragtime thing—did they have a mindset? What do you mean this came to you?

It came to me, and it came to us. Kaufman and Ritter had talked amongst themselves and brought the piece to me. Then it revealed itself to us more as we were writing it.

Got it. It was this arranged organic process that took off once you all got together.

Yeah, we had no idea what we were looking at or looking for. It all revealed itself through the sessions.

This question is not meant to sound vampiric: The two Joshes, the National, doing the Dead with John Mayer and Trey Anastasio. Are you purposely playing with cats outside your usual circle or younger players because you’re looking for a fresh coat of paint? Or are they great players, and age be damned?

Definitely the latter. If I’m working with younger guys, there’s always a certain amount of stuff I can impart after having played for a long time. Overall, though, I’m just looking to interact and to live it. To work with what they have to offer. It’s the back and forth.

Let’s look at how and what the National did in curating Day Of The Dead with alternative bands—and you—as part of the bigger Grateful Dead picture. What was your take on how they viewed your legacy?

It became real apparent to me—quickly—that what they hear is what I’m hoping people will hear. The National, for instance—I can hear in their playing what they heard in me; the roots thing that I’m working from, the heritage of country or whatever. Insofar as we revere the same traditions, we speak the same language, and that means we can converse easily.

There’s a fantastic photo of you, your daughter and your wife at the San Francisco Debutante Ball with you in dashing white tie and tails. What are you thinking?

It wasn’t my first Debutante Ball. I attended one in my youth, and we certainly played them. There’s a tradition. I had separated myself from that world for years—not renounced—but it creeps back in, especially where my older daughter is concerned. I was kind of tickled about that. I was born and raised within that dynamic.

You were forever the clean-shaven pretty one in the Dead. Not that you’re not still pretty, but what’s with the General Burnside beard? It’s gorgeous. Why grow it?

I was just on the road and missed a few shaves. Those several days turned into a week and a half, and the next thing you know I looked like a Civil War cavalry man. It just kind of happened.

On the new album, lyrically, you’re working with Ritter. It hit me—you’ve collaborated with other wordsmiths in the past. What level of trust must you have in someone to let them tell your story?

There’s a lot of back and forth, and rather than trust, I would say we share vision. That’s openness toward those involved, and Ritter’s one truly open individual.

Do you recall what song came first during the Blue Mountain sessions and how that guided the rest of its vibe?

I do. The title song—it’s like a cowboy tune, a place to hang our hat and to let the other songs circle around. It was a bunk house in Wyoming where I began that.

It’s not as if you haven’t worked on other projects since 1978, but Blue Mountain is the first to have your name out front, in lights, all by its lonesome. Why is that?

The other albums—they’re all me. This is just a little more me.

—A.D. Amorosi