Here’s an exclusive excerpt of the current MAGNET cover story.

Interview by Fred Armisen

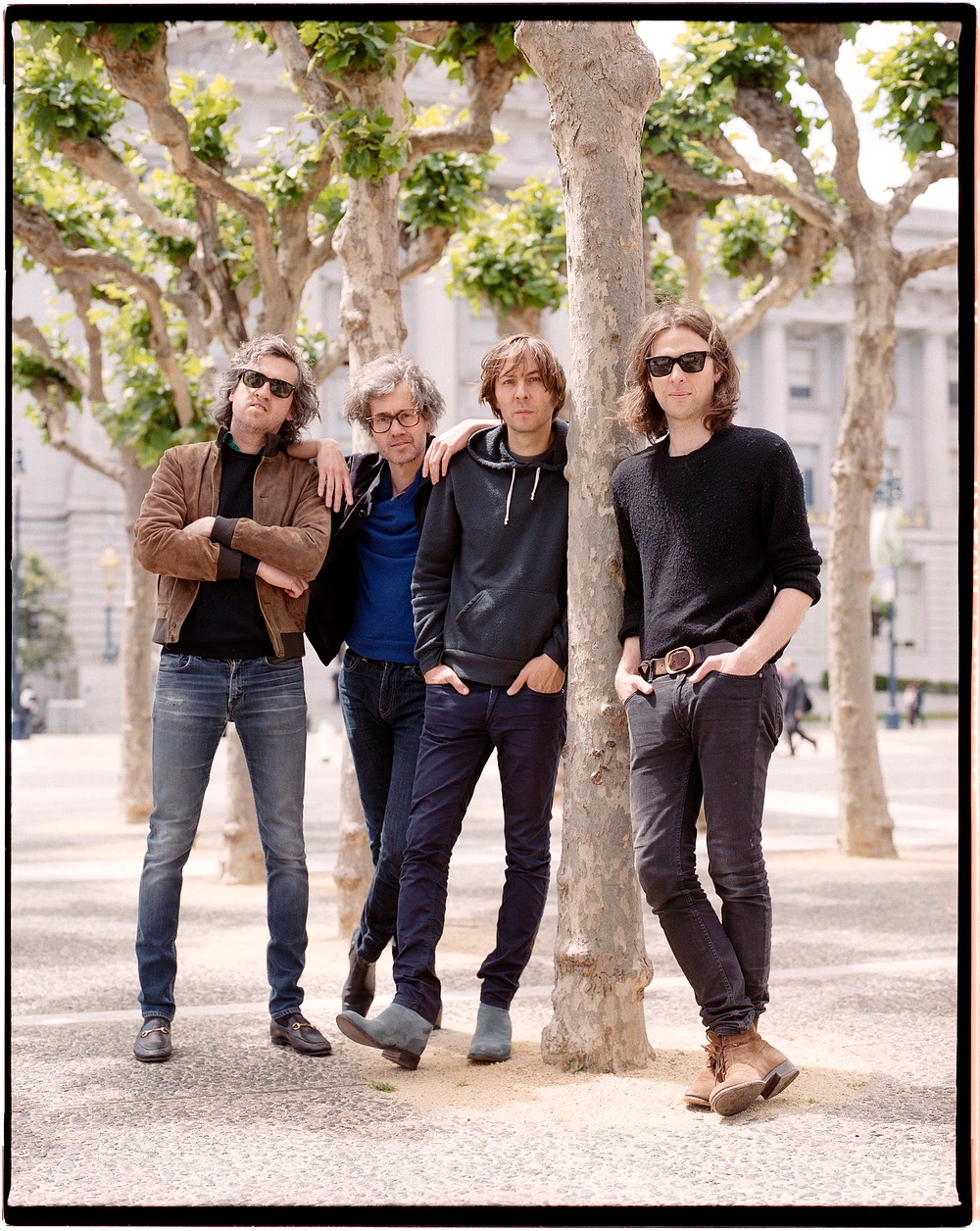

Photo by James Elliot Bailey

With the vibrant, neon-lit synth pop of Ti Amo, Phoenix scores the summer with an album destined to rule outdoor festivals and Italian discos alike

The narrative I made up in my head for Phoenix’s new album, Ti Amo, is that, aside from a celebration of Italian nightlife, it’s a reply to the Style Council’s debut mini-LP, Introducing The Style Council. That record may have been my first experience with an idealized location as a concept. In their case, it was Paris. Track nine on Phoenix’s album, “Via Veneto,” feels like part two of “Long Hot Summer.”

I didn’t bring any of this up during my interview with Thomas Mars, because none of it is a question. It would just have been me saying, “This is what I think.” I did mention Kraftwerk, though. Trans-Europe Express has a similar theme.

I’ve always loved Phoenix. As soon as I heard them, I thought they were great. It was a nicer surprise to find out, too, that they are from France. To me, their scene went like this: first Téléphone, then Les Thugs and then (although they aren’t technically 100 percent French) Stereolab. Then Daft Punk, and now (I realize that “now” has been going for a long time) Phoenix. This is just my version of it; I hope that’s OK.

The following setups aren’t true, but you can pretend:

I spoke to Thomas while we were shopping for cars in Kyoto.

I spoke to Thomas via passing notes during a play.

I spoke to Thomas 20 years ago, in line at Disneyland.

I called Thomas at home and got his machine, and then he called me back and got mine. So these are all left messages.

Thank you!

—Fred Armisen

Fred Armisen: I’m glad I’m getting to interview you because I’ve known you for a while and I’ve always enjoyed watching your success. You guys—the whole band—seem like such a strong unit together.

Thomas Mars: Yeah, we’re friends from school, which is a unique chance because I think when it’s your second band, you know too much. It can’t be as genuine when you’ve had those experiences before. When it’s the first time, it’s more naive and genuine, I guess. I can’t really compare it to anything else.

Armisen: When you were a kid or a teenager and you imagined what it would be like to be in a band that makes a living being a band, what came out to be true and what are some unexpected things?

Mars: That’s a good question. No one’s asked me this question before, but I feel like that’s the question. When we started, the first feeling that was really strong was that there was something with friendship and music. The two things together were really strong and the fact that you hear sounds that are amplified, just a kick drum that’s amplified. To me, when I would go to a show, even when you would hear a band soundcheck, this was so strong because it was already out there. It had way more power, and that was a big thing for me. When we started the band, we thought the day the record would come out, the world would change. That’s something that didn’t happen. The day the record comes out, everything’s pretty much the same. Our success was really, really slow. Sometimes, a song would be big in one country so we would go there and experience these, like, Italian TV shows. We had one song big in Italy and lived this adventure which was really part music, part comedy, because you end up in one of those TV shows where they mix music and soccer, and you have a nun that’s introducing you. Just far-out experiences. When we started music, we didn’t want to be responsible. We didn’t want to have a job, and the fact that this is our job and doesn’t feel like one—I think we treat it like a job. We make a point that we have office hours. When we started, we were even wearing ties and suits because it was such a miracle that this was our job. It made it even more special. I’ve seen other bands do that, treat their job like it’s a factory. I know the Beastie Boys have these outfits and they bring this factory business, because it’s such a special thing that this is what we do.

Armisen: That’s kind of the answer I was hoping for. My hope is always that if someone is in a band that they’re appreciating it. It’s a rare thing to be able to make a living at it; it’s even more rare to stay together. It’s a real feat, and that description, down to the kick drum through a PA, it’s so funny because it is such a different sound, the kick drum you hear in the soundcheck and what a kick drum really sounds like. It’s like the bridge between practicing and doing it for a living.

Mars: I remember watching a video of you just going through Stockholm and inventing your own stories, am I right? Is that a video?

Armisen: Yeah, I did that. I was promoting Portlandia there and so there was a camera crew, and they just wanted to do something. And it was that feeling of, “If I get to be in another country and then do some kind of creative work, there’s nothing better.”

Mars: That I could really relate to, because you’re not passive. You’re creating something, not just promoting. I grew up in Versailles, which is a city that’s like a museum, so everything great already happened and you can’t really change anything. Just making music is disturbing the peace and is not considered being respectful. So to me, to create those stories, even to invent and bring back those places to life or create this world of possibilities—that’s the thing I think about quite often. You know, when we go to Buenos Aires, we pass Jorge Luis Borges’ house and you don’t want to be totally passive. You have to create those stories.

Armisen: Every time you guys put out a record, I feel like there’s a theme around it. Phoenix reminds me of the way that Kraftwerk put out records. They have a vague idea for what the graphics are gonna be and it gets sharper and sharper, and then I see the video for “J Boy” mentions Kraftwerk and I’m not ahead of the game in thinking that you guys are like them. In Düsseldorf, Kraftwerk has Kling Klang Studio and they clearly have some kind of a work ethic. Listening to Ti Amo, I have no idea how you come up with sounds. It’s easy to say, “Oh, they use sequencers or synths.” What’s a simple version of what you guys use to put everything together?

Mars: Kraftwerk is the best compliment for us, because that’s the band I can relate to the most. Not musically—I love that music, too—but the work ethic and how pure the message is and how the aesthetic is more than music. It’s an entire concept, and that’s such a strong thing, and rare. I remember seeing a documentary where the English bands were saying, “We saw Kraftwerk in Manchester and it opened things up. We started a band because of them.” I think when we write songs—the four of us, I know they do the same thing—I try to impress my friends. I try to come up with sounds and with ideas that they might not be able to tell what it is. With technology now, I can become bored with my voice, I can change it. If I play drums, I do a weird hybrid mix of samples, drum machines and real sounds that get a little confused. I think we create this color palette that has to be unique. The only decision we make is to create this environment that has all these unique sounds that we like. And then it’s mostly luck; we record forever. Our brain wants to do something familiar and we have to fight against this, we have to find what the next familiar thing could be—that’s the goal. We just record a lot of things and then we try to put these together, but we never thought about instruments separately. Now the guitars, the keyboards, even the vocals, they can pretty much imitate each other. Chris Mazzalai in the band has this guitar pedal that imitates a Japanese voice. You play the guitar through that pedal and it’s like a Japanese woman that’s talking.

Armisen: What!? What’s it called and who makes it?

Mars: I don’t know the name of it.

Armisen: What does it look like?

Mars: It doesn’t look like much. It’s the size of a Boss pedal and it’s white and has a drawing of this Japanese girl on the side and a Celtic font, almost like those wedding invitations. You play through it and it has a wah-wah thing to it, and then it shapes the notes. It doesn’t create real words, but it imitates the sound of a Japanese person talking.

Armisen: Does it hold a note?

Mars: Yes, but it it’s like [imitates noises].

Armisen: What is your relationship with your drummer and keyboard player? Where do they enter into your daily life or your touring life? What is that relationship like?

Mars: The keyboard player, Robin Coudert, we’ve known since our teenage years. He was in another band and we grew up together. I think he was on the same label as us for one song. He recorded one song on this compilation that the label did and then we stayed in touch, and he now scores movies. But when we go on tour, we love each other so he comes along, and he’s a friend since, what, 16? And our drummer, Thomas Hedlund, we met while touring in Scandinavia 10 years ago. He has a few bands. He has a band where he’s a full-time member, which is called the Deportees, as a band where he plays various styles. He has a death-metal band where they have two drummers. He’s so good that I stopped playing drums. I used to play drums sometimes even in the studio, but because he’s so good I just can’t. I don’t want to play drums anymore. Sometimes with technology, we totally don’t need a drummer in the studio, but he comes to record additional drumming for what we’ve done, or sometimes he has ideas to make it more elaborate. That part of our band, they are with us six months … when we tour, we are together all the time. We sleep in tour buses next to each other, so we know each other pretty well.

Armisen: It’s so nice that it’s been the same people so it’s not always some session person you haven’t met. That’s kind of cool that it’s part of the band.

Mars: Unless you’re a bit of a dictator onstage, unless you’re James Brown and you say, “No, you do it like this.” But that’s not our personality. It would be a struggle. It would be horrible to work with session musicians, I think.

Armisen: Do you have one recording studio, or do you guys bounce around?

Mars: We bounce around. Each record, we have a different studio because I feel like if you have your own, it’d be too comfortable. It would feel like Groundhog Day even more. Also, I know that my favorite Prince record—well, before he had Paisley Park—I feel like it’s good to have something new each record. Do you have a studio?

Armisen: No. We shoot on location everywhere, so it’s even further of an extreme of not having comfort. We have an office that changes every couple years, and every day we have to go to some location. It’s really nice to hear you say that, because I firmly believe in not having the most comfortable situation always, exactly for that reason. As soon as people get their own TV studios or recording studios, the more comfortable it is, you can feel it. You can tell that they slept in and came in late, and I don’t know what it is. One time—and I mean no disrespect for any TV shows—but one time I went to a studio at NBC where they filmed the old Tonight Show, the Jay Leno one. Everyone’s great, he’s a funny comedian, but they had a big painting of him up against the wall at his actual studio and it was so permanent. Something about that, I was like, “As soon as you get settled into some permanent ‘This is my home, this is where I’m gonna make my music from,’ I think it’s trouble.” It should always seem a little shaky just so you work a little harder.

Mars: When it becomes a museum, it’s the same idea. It becomes intimidating and forces you to replicate some recipe or something. It doesn’t invite novelty, for sure.