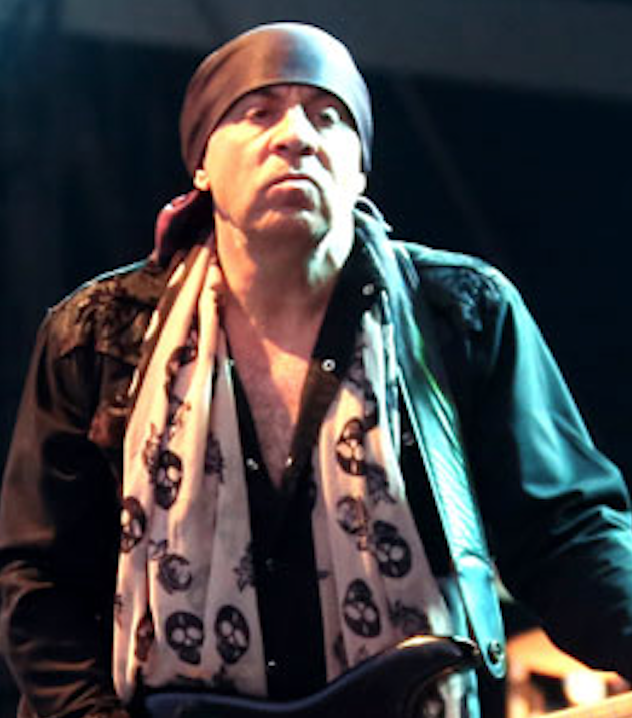

Little Steven Van Zandt is taking a respite from Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band with the release of Soulfire, his first solo effort in 18 years. Not a total break, mind you: Soulfire includes one song co-written with Springsteen, “Love On The Wrong Side Of Town,” along with others Van Zandt penned and produced for pals Southside Johnny & The Asbury Jukes, such as “I Don’t Want To Go Home.” Still, we’re used to seeing and hearing Van Zandt not being Boss-ed around. Over the past 14 years, he’s hosted his Sirius XM radio channel Underground Garage and played Silvio Dante in HBO’s The Sopranos and Frank “The Fixer” Tagliano in Netflix’s Lilyhammer. What the jazzy, bluesy, brassy, blaxploitative, doo-woppy Soulfire does is return Van Zandt to the singing/sneering/writing role he led on solo albums such as the furiously and politically charged 1982’s Men Without Women and 1984’s Voice Of America, both precursors to his 1985 creation of music-industry activist group Artists United Against Apartheid.

Audiences love you as an actor, a musician, a radio host. You’re an adorable guy. What are they connecting with?

That’s true. I’m a helluva guy. What can I say? I basically mind my own business. I go to work every day. I’m a working-class celebrity. It’s a job that I do, which is nothing more special than any other job anyone else does. I even go to an office.

What is it with you and Norway? You filmed Lilyhammer there. You’re starting your Disciples Of Soul tour there.

It’s a place I adopted, or that adopted me. It didn’t used to be on the rock touring circuit, and when I started my solo stuff, I told my agent then, “I want to go everywhere.” He included Norway and I fell in love with it. It’s unique, quiet, five million people spread across a large expanse. Plus, a Norwegian husband-and-wife team offered me Lilyhammer, so I spent six years there on and off. I got to know the place pretty good, you know? Hey, they named a blues school after me in Norway. It’s the blues capital of the world.

Before Soulfire, your solo stuff was deeply political and incendiary. What’s your take on the whole mad Trump thing?

That’s a big question. I think our problems have more to do with the system than Trump. He’s a distraction, more often than not, from the bigger issues, especially within the Republican Party. Especially those regarding climate change, equality and money. These are greater issues than just one guy. At the end of the ’80s, when I was doing nothing but politics, I came to the conclusion it all comes down to one issue: financial inequality. Until that’s changed, there will be no economic justice, at least nothing like our founders envisioned. I appreciate Bernie Sanders and his whole Citizens United thing, but that wasn’t the right way to a solution.

So on this new record, there’s nothing at all political?

My mind regarding my music right now isn’t political but, rather, the hope that old great rock ‘n’ roll—the renaissance period of 1952 to 1972—gets heard. That’s the greatest generation.

How very Tom Brokaw.

Well, all that is distinctly rock ‘n’ roll, at this point, is an endangered species. I want to make sure that the stuff that motivated us—or at least me—in the first place stays alive. That means James Brown, the blues, street-corner doo-wop.

And that whole Jersey Shore/Asbury Park, horn-based R&B/rock thing—all the Southside Johnny stuff, your first solo album.

Well, that sound suits me again now. That’s what I wanted to do with this album: do me. I usually write with some larger theme. This time out, I became my theme. That’s why I covered my old songs. It’s the best way to reintroduce myself to me, as well as an audience. Plus, I wrote a few new songs along the way for whoever is interested.

Since you’re talking to yourself or about yourself in the third person, how do you reconcile the romantic behind Soulfire with the guy who wrote “I Am A Patriot,” which proposed that dissent was not disloyalty à la Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden?

I got about a dozen guys living inside me … that’s two of them. There’s a bunch I haven’t met, and deep down they’re all integrated. Once Chuck Berry started talking about real life in his teenage operas, then Bob Dylan took it further with the socially impacted political fare, all of it is fair game.

To paraphrase Frank Sinatra talking to Rita Hayworth in Pal Joey, 18 years is a long time between drinks. What gives?

Pal Joey. You’re good. That’s a great question to which there is no answer or excuse. Suffice to say, I got busy with other work—especially acting and producing—and the whole craft. That craft, gifted to me first by David Chase, gave way to other crafts like writing the soundtrack to Lilyhammer and directing the last episode. Then Bruce decides to put the band together again, so there’s that—and touring it quite regularly, too, all of a sudden. Before you know it, 20 years go by.

Well, that’s everything, though. You blink and a year passes. So what do you do now—hopefully more music?

Well, I’m not a guy to hold back material. I don’t stockpile. I tend to write with purpose, so there’s that. Some of my music in the last 10 years went to Lilyhammer. My past solo albums are all out of print, so that’s another thing to be done: get them remastered and re-released. Know what else? I never had a manager before this year, so I did that. There’s gonna be more music, too. Ever since I got this request to do a blues fest in London last year and revisit songs I did with Southside Johnny—songs I never played live—I actually felt guilty that I had those songs and that I put my soul, you know, music aside for so long. No more, though.

—A.D. Amorosi