News travels fast in the digital age, but back in the middle 1970s it took months for a British or American rock magazine to sail halfway around the globe to Brisbane, Australia. Every word or song that made that trip was precious to teenagers Robert Forster and Grant McLennan. Nourished by dreams of rock ‘n’ roll, poetry and art films, they willed themselves to become singer/songwriters and in 1977 founded the Go-Betweens.

Starting with 1978 single “Lee Remick” b/w “Karen” (a pair of Forster-penned songs that praised a movie crush and a librarian, respectively), the Go-Betweens navigated the mercurial vagaries of a music business that valued video flash over sharp writing skills and recorded a half-dozen brilliant albums. Exhausted and riven by the same internal tensions that sparked some of its best songs, the band split after 1988’s perfect-pop 16 Lovers Lane failed to break through, and Forster and McLennan commenced solo careers. But even when they were recording records that differentiated their respective aesthetics from the Go-Betweens’, the songwriters never fell out of touch. A second go-around in the early 2000s yielded four more excellent albums before McLennan died of a heart attack in 2006.

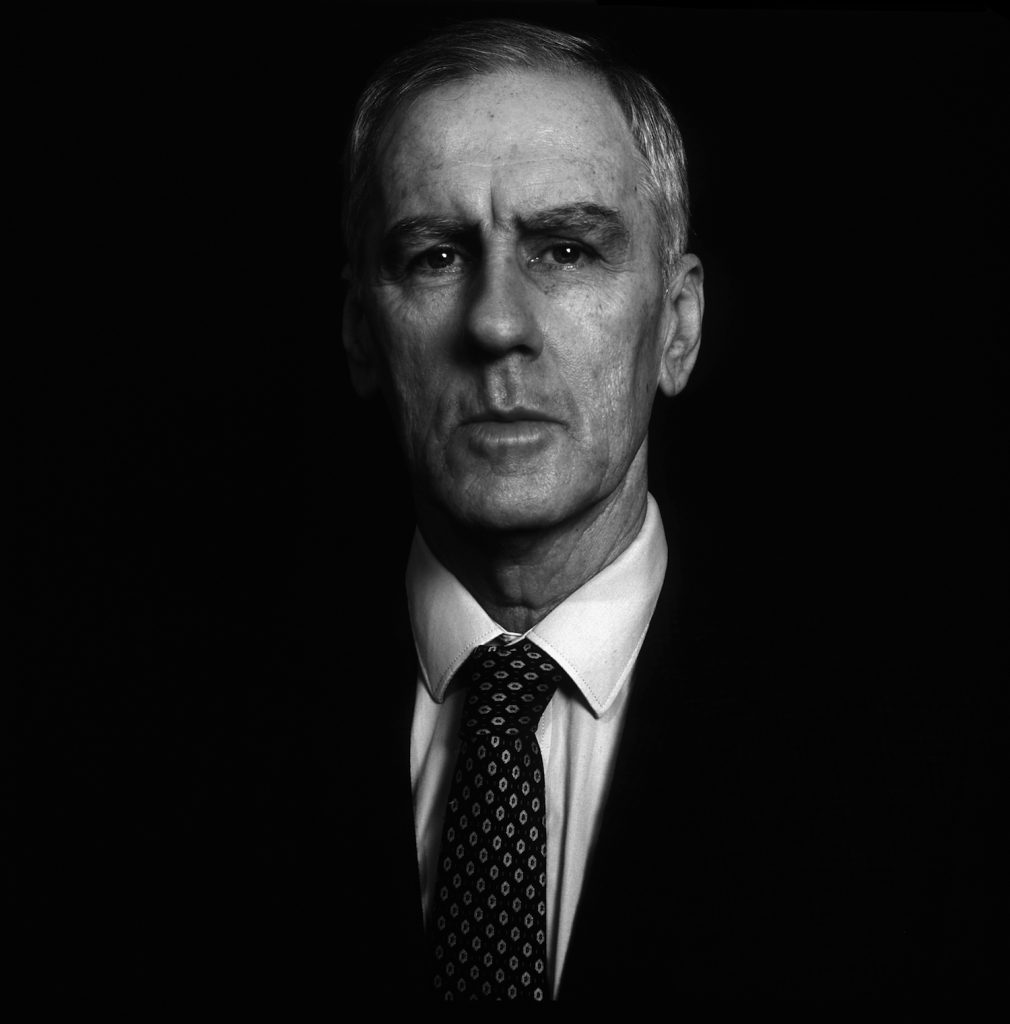

Since McLennan’s passing, Forster has spent his time writing for Australian periodicals, assisting in the compilation of a boxed set covering the first six years of the Go-Betweens’ career, writing songs and the memoir Grant & I: Inside And Outside The Go-Betweens. The new Inferno (Tapete) is Forster’s seventh solo album since 1990. To record it, he left Brisbane, where he and wife Karin Bäumler have raised two children, and spent several weeks in Berlin during one of its steamiest months on record. Its songs set elegantly told personal stories—some autobiographical, others overheard—to lean, timeless music.

You took up writing about music. Where is your writing published nowadays?

I don’t write music criticism anymore. I used to write regularly for an Australian publication called The Monthly, but I stopped in 2013.

What music, either old or new, has moved you in recent months?

I haven’t listened to much music over the last years. Most of my time goes to writing prose or songwriting. So I tend to hear a song here or there. Recently I have been listening to “Letter To Hermione” from David Bowie—a beautiful acoustic song from the late ’60s. Maybe his first great song. And just yesterday I heard “All Things Must Pass” by George Harrison—a hole in my musical education. Both great late-’60s songs.

Your son Louis is in the band Goon Sax. Is there any advice that you have given him as he moves into the family business that you would like to also share with MAGNET’s readers?

I give him little advice. A piece of advice I give to every band is: Don’t say yes to every show you get offered. You attract attention when give the odd no. People are used and comfortable with a constant line of yeses.

Your wife has performed and recorded with you. Does your daughter also play, and is there a possibility of a family band down the road?

I like the idea of family bands. They should happen more often. But I don’t think it will happen with us. Our children must make their own way for a good while.

A boxed set of the Go-Betweens 1978-1984 was compiled and released a few years back. Will there be additional sets covering the rest of the ’90s and the 2000s?

Yes there will be a second volume The Go-Betweens Anthology. I am expecting it to come out towards the end of this year. It shall cover the years from 1985 to 1989.

When you first recorded in Berlin circa 1990, you were starting something new. What was the objective in returning to Berlin to record Inferno?

The reason I recorded Inferno in Berlin has much to do with the producer and engineer of the album, Victor Van Vugt (Nick Cave, PJ Harvey, Beth Orton). He lives there, and he has a studio there. That was why we recorded the record there.

Last summer was a scorcher in Europe. How inferno-like were your living and recording circumstances in Berlin, and was your usual life in Brisbane sufficient preparation?

Berlin last May and June when I was there recording Inferno was tropical Berlin. I was travelling on the underground railway to the studio—the U-Bahn—and it was very, very hot down there. Inferno-like on the way to record an album called Inferno. The irony when taking the journey each day to the studio was not lost on me.

In your book you describe being charmed by Bowie’s “Starman” in your youth, and “Inferno” sounds more Ziggy-like than anything else that I remember you recording. How did this come about, and what took you so long?

I don’t know why it sounds so Ziggy-like. It was a coming together of instruments and sounds in the studio, and suddenly there it was. I am amazed I haven’t done more glam-rock type stuff in the past, as it was a major part of my world as a teenager. Expect more.

What tour plans do you have to support Inferno? Might the USA be on the itinerary?

I will be touring parts of Europe and then Australia, and at the moment the USA is being scouted for me to play. I haven’t been there for 11 years, and I wish to return and play. We are trying to get there.

—Bill Meyer