MAGNET’s Bill Meyer headed to Latvia to experience the coolest adventurous-music festival you’ve never heard of. Photos by Arnis Kalniņš (Riga Bourse Museum) and Artūrs Pavlovs (Hanzas Perons).

Riga, Latvia, earns its designation as a Unesco World Heritage Center with an array of architectural treasures ranging from medieval times to the heyday of Art Nouveau. But take a bus into town and you’ll see ranks of crumbling, Soviet-era apartment blocks. The nation was stuck behind the Iron Curtain from the end of World War II to 1991, and Soviet republics did not go out of their way to nurture progressive art.

Since regaining independence, the Baltic nation has redefined itself culturally and politically, and the Skaņu Mežs Festival For Adventurous Music reflects that process. Since 2003, it has imported creative sounds from an array of genres, staging them alongside homegrown artists who bridge contemporary creative strategies and a middle-European classical tradition.

Skaņu Mežs is part of SHAPE, a confederation of festivals and art centers located in smaller European cities that are dedicated to popularizing innovative sound and visual art. But among this company, it punches above its weight; the 2019 lineup transcended the mostly electronic orientation of many of its fellow events and stands up to genre-mixing festivals sponsored by Red Bull and The Wire. It took place over the first two weekends in October. The first concert was a free event staged in the covered central courtyard of the Riga Bourse Museum that included a panel discussion about experimental music under authoritarian regimes, two sets of classical music originally conceived under heavy manners, ritually informed improvised music, plus the first performance in 10 months by Circuit Des Yeux.

During the panel discussion, German DJ Alexander Pehlemann observed that in totalitarian times, people didn’t set out to be underground musicians. “Your parents and the policeman on the corner defined what was underground” he said. “Musicians were assigned the status by being banned.”

The concert included sets devoted to late Russian composer Edison Denisov and Portuguese composer/educator Cândido Lima, both of whom advocated for music that was not sanctioned by the state. The 80-year-old Lima was feted with a retrospective that traced the evolution of his uses of electronics from a practical tool for augmenting pensive piano compositions to a means of generating stand-alone alien sound. An unnamed local chamber group successfully met the technical demands of Denisov’s jagged “Trio,” faithfully rendering both the piece’s emotional opacity and its foregrounded structural challenges. You wonder if such qualities were survival strategies to get past censors?

The main thing that French bagpiper Erwan Keravec had to get past was his instrument’s folkloric and martial baggage. These he handily subverted with an improvisational and spatially conscious approach that directed multiple streams of sound against the corners of the space, then stirred them back together in a hypnotic maelstrom of mind-melting continuous tones.

American duo Subtle Degrees was even more transcendent. Tenor saxophonist Travis Laplante alternated repetitive and elongated phrases, which interacted with the room’s lively acoustics to create the illusion of an ecstatic reed choir ululating over drummer Gerald Cleaver’s spare, strategically paced grooves.

Chicago’s Circuit Des Yeux closed the night with a set very different from the Reaching For Indigo show that singer/songwriter Hayley Fohr retired late in 2018. For Skaņu Mežs, she left her band at home and performed with only 12-string guitar, which was augmented by pedals and synthesized loops. Fohr played mostly new material, using her minimal instrumentation as a launching pad for dynamic vocal forays that forged complex emotional effects derived from the cavernous depths of her voice and the telegraphic narratives conveyed by her lyrics. While certain songs contemplated alienation, their cumulative message was a positive one. Commenting on her eye-catching red attire, Fohr declared herself to be the canary in the coal mine. “I am telling you, it is safe to mine.”

After an evening music that pondered the past or centered the listener in present focus, it felt good to be sent out the door looking optimistically to the future.

The festival proper took place the next weekend in Hanzas Perons, an old stone train station situated inside a glass enclosure. Each night’s program encompassed classical, noise, electronic dance and something akin to rock music. English violinist Irvine Arditti’s selection of solo pieces (by Salvatore Sciarrino, James Clarke and Robert H. P. Platz) were all rich in tonal variety and allergic to repetition. While they offered none of the comforts of contemporary minimalism or the classicism of past centuries, their density of event, rendered by Arditti with exacting attention to detail and proportion, made for deeply rewarding listening.

Another English musician, Lucy Railton, proposed an equally challenging but sonically quite different answer to the question of what a classical string player should be doing in the 21st century. Initially, her cello rested untouched while she sat at a table covered with electronics and unleashed a blitz of jagged glitches, glassy swells and field recordings that assaulted the senses like a big-city rush hour. The barrage abated when she switched to cello to provide a brief, luxuriant tone bath, only to resume when she switched back to electronics in order to transform the sounds of her strings into a fractal explosion of ascending pitches.

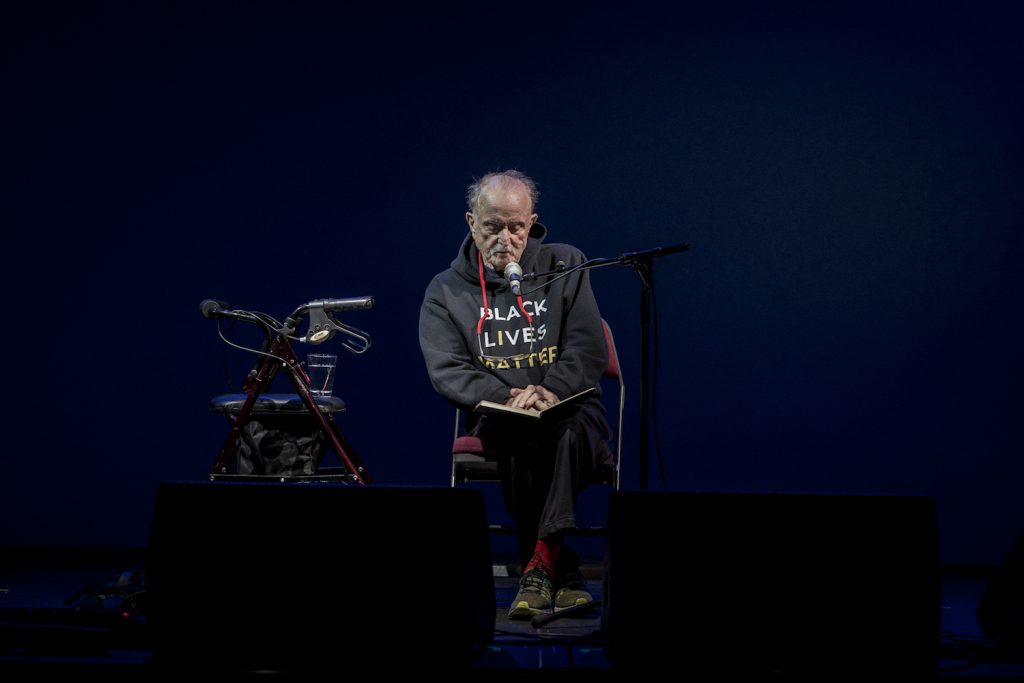

The festival’s most powerful appearance was one that could easily not have happened. This spring, American experimental composter Alvin Lucier broke six vertebrae in a fall. Even though the 88-year-old musician can barely navigate without a walker or wheelchair (and his voice can no longer rise above a whisper), Lucier came to Riga—without telling anyone from the festival of his condition. He kept a workshop for young composers rapt, explaining his original impulse to create music that didn’t reference any known musical language. He also pulled out his iPhone to play a lovely string piece that he’d recorded just three days prior.

Alvin Lucier

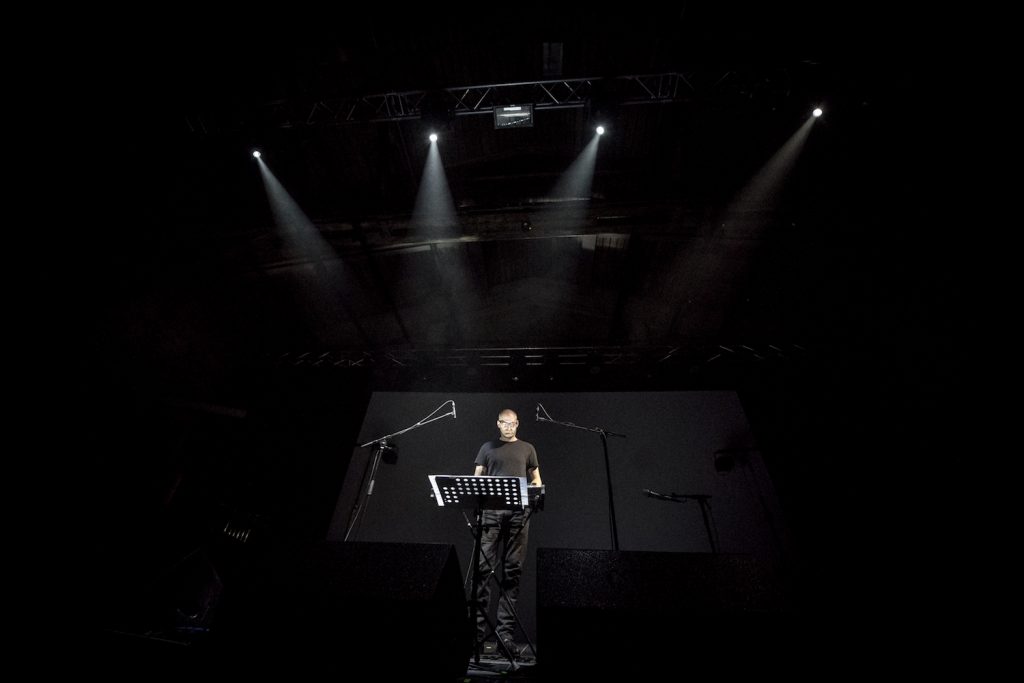

Trevor Saint

On Saturday night, percussionist Trevor Saint played a pair of Lucier’s pieces for glockenspiel. Each used the interaction between simple patterns and the room’s acoustics to create music of psychedelic density. Then Lucier, attired in a Black Lives Matter hoodie, took the stage to perform his classic piece “I Am Sitting In A Room,” which involves reading a text, recording it, then continuously playing and recording the piece until the words disappear and only the room’s resonant frequencies remain. Originally conceived as a work that drew attention away from the performer and toward the space in which the music was performed, it revealed itself on this night as music that allows a performer to transcend his infirmities.

Michael Gira

Norman Westberg

Two members of Swans presented solo sets on Friday night. For most of this decade, Swans concerts have been titanic experiences that have used extremes of volume and duration to take both performers and audiences into a state of ecstatic abandon. But in 2017, Michael Gira disbanded the group. Brand-new Swans album Leaving Meaning sounds as vast as anything else the band did during those years, but at Skaņu Mežs, Gira stripped them back to the essentials. His rudimentary, percussive guitar playing was like a shamanic drum beat, his exquisitely controlled singing entirely up to the task of turning the songs’ extravagant imagery into ego-obliterating incantations. It fell to guitarist Norman Westberg to carry Swans’ flag of endurance. He used one guitar and a table full of pedals to generate an hour-long piece of gradually evolving music. First, he built up series of loops like oceanic swells, then introduced counter-signals that troubled the waters like rogue waves. As the music heaved and bobbed, Westberg inserted brief phrases that flickered like passing shoals of little electric fish.

Terrence Dixon

Aaron Dilloway

The festival also presented a broad spectrum of electronic music. Detroit techno producer Terrence Dixon crouched behind a table set with drum machines and a sampler, which he mostly used to give the audience plenty of crowd-pleasing, body-moving beats. But during one sequence, he faded down the kick drum and proceeded to stack layers of Latin hand percussion, jazz drumming and snatches of dialogue from The Six Million Dollar Man. Then, in a moment of sublime surprise, he dropped it all to make space for Sun Ra’s “Watusi.”

Another dance act, Englishman patten, delivered a sensory experience so visually overwhelming that it was easy to overlook the fact that he essentially stood motionless behind his laptop throughout the set while laser lights blasted overhead. He showed little evidence that he was making any musical decisions at the moment of performance, but his tracks, which showcased an encyclopedic grasp of electronic beat styles, got the audience moving.

Oberlin, Ohio-based Aaron Dilloway took a more antic approach to performing with playback devices and electronics. His main instruments were a stack of eight-track tape machines and some contact mics, which ended up in his mouth or on his body. Each mouth noise, Frankenstein-ian jerk of the limbs or kick against the wheeled box that he used to schlep some of his gear corresponded to an essential blurt of noise, which he then layered into repetitive loops and misshapen crashes that grounded against each other on their way to moments of exhilarating collapse.

Local EDM performer Posverdad Trax’s festival-closing set made his visual presence irrelevant by matching the blown-out destruction of his beats, which blurred into a crushing wall of sound, with blasts of blinding white light.