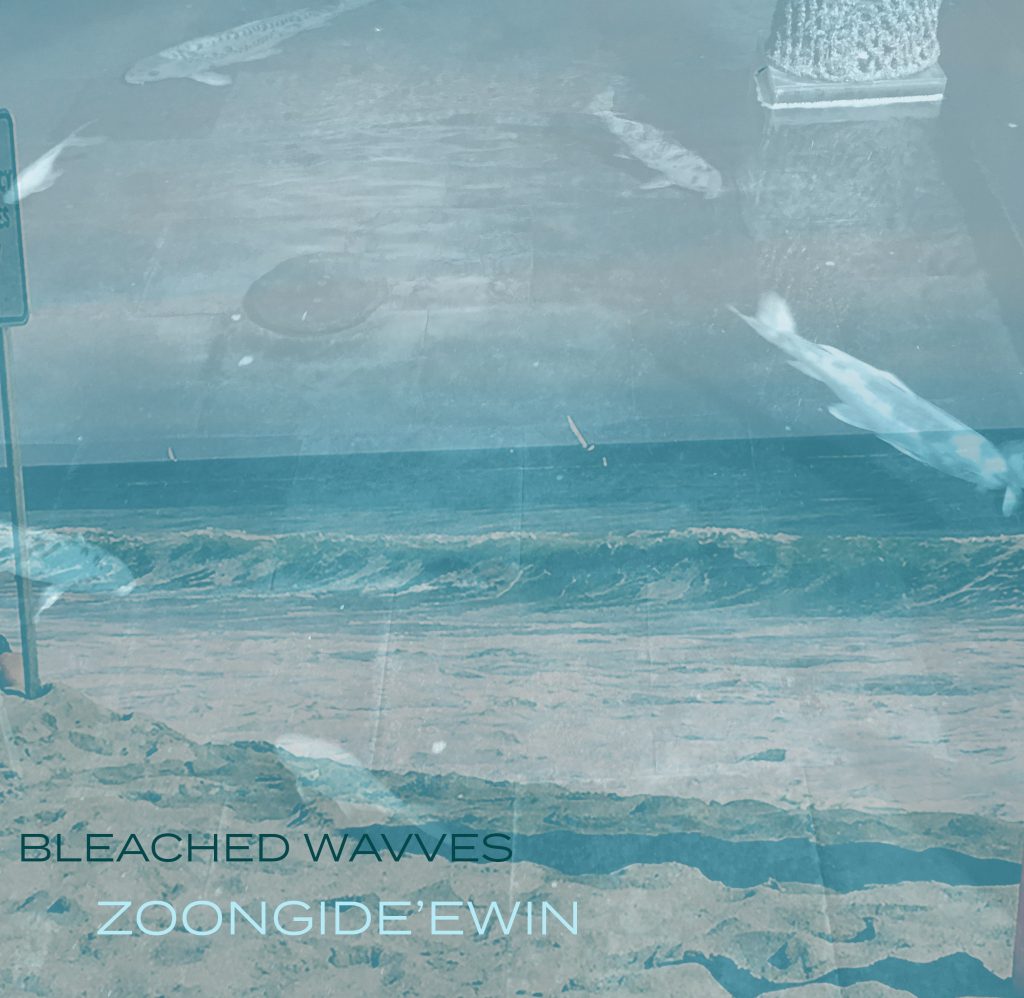

While Zoom’s stock price continues to soar as most of the world is stuck at home, Zoon’s stock should being rising soon as well. On June 19, the Paper Bag label will release Bleached Wavves, the debut album from Zoon. For the uninitiated, Zoon is Daniel Monkman, an indigenous Canadian musician who describes his output as “moccasin gaze” (a mixture of shoegaze and traditional First Nations music, obviously).

Monkman named his musical project after the Ojibway word “zoongide’ewin,” which means bravery and courage. He did so to recognize his ongoing journey back from his active drug and alcohol addiction. Aside from its gorgeously ethereal washes of sound, the 10-track Bleached Wavves is also powerful in the hope it inspires in its listeners. The album-closing “Help Me Understand” is one of many standout tracks that does just that.

“‘Help Me Understand’ is from a short story/poem I wrote about an unknown First Nations protagonist who lives homeless on Vancouver Island,” says Monkman. “While homeless, they become very ill. While no help is to be found, they accept death, and while on their last moments, they’re greeted by the creator, who welcomes them into the heart of the sun.”

Monkman enlisted Justis Krar (IMMV Productions) to direct the trippy video for “Help Me Understand” as well as the clip for fellow Bleached Wavves track “BrokenHead.”

“Making the videos challenged me to create visuals that both conveyed the intent of the song as well as facilitating an abstract narrative,” says Krar. “Daniel was integral to the process as he guided me toward visuals that represented indigenous concepts or stories that I had not had the chance to work with before. I love these songs dearly and am happy that Daniel choose to work with me.”

“I gave a little direction for the video but mostly left it up to Justis,” says Monkman. “I explained to him the story behind the song and where the lyrics come from.”

Whatever Monkman’s contributions to Krar’s video for “Help Me Understand” were, the end result is one you won’t want to miss. To that end, MAGNET is proud to premiere it today for your eyes only. Check it out right here, right now, and read our Q&A with Monkman after the jump.

Q&A With Daniel Monkman

Much of Bleached Wavves speaks out against the hardships you faced growing up as a First Nations person. How did creating this record help you overcome those obstacles?

When I first began writing the songs on this record, I was in and out of rehab programs. I found it difficult to relate to the way that these places were trying to teach healing. Because of this disconnect I had been feeling, I decided to begin visiting indigenous programs and elders. From this I learned more about my culture and how healing can start to happen in a way that I could understand and relate to. I guess this record and healing/connecting with myself as a First Nations person happened simultaneously, so in that way, they are deeply connected. I think about how oral storytelling is important in First Nations culture and how making music has become that tradition for me. To help me understand myself, to learn, grow and heal.

“Help Me Understand” speaks on many of the issues First Nations people face every day. Especially the lack of help this protagonist receives. Was this story something you worried about potentially facing when you were overcoming adversity?

Yes, I was very worried about my life becoming something like the protagonist’s. The way my life was going at that point, I definitely would’ve ended up homeless and without support. I’ve always been hyper aware of the rapid growth of technology, and I wondered about what our elders, who are homeless, think. They had childhoods in the bush and learned from their elders, and now some are homeless and dying on the streets without family. This concept really haunted me for a very long time—it pushed me to the edge of insanity. Almost to the point of no return. At times, I felt like it was my destiny to lose all hope and wither away. But while on the island, I found out about an indigenous recovery program and learned about my traditional past. That’s what saved me from those negative thoughts of failing.

Can you talk about the Seven Grandfathers teachings and the effect it had on you becoming sober and a musician?

Well, I tried AA and many other support groups, but I found they always pushed the Christian god and that always brought up a lot of bad memories for me—intergenerational memories. My father was put in residential school as a young boy, and the missionary did horrible things to him. So when I was older and learned about those schools, it was hard for me to fully accept some of the AA beliefs. But I very much respect the work they do for others who are in need of guidance. Once I found out about the Seven Grandfathers teachings, I finally felt a connection within myself come alive. I felt like there was this foundation that was locked away, but once I unearthed it, I was able to build my spirit up again. My artist name is Zoongide’ewin, and it is part of the the Seven Grandfathers teaching. It means “bravery” and “strong heart.” Getting sober taught me a lot about bravery—being brave enough to give up the one thing that would help me cope with my trauma was an enormous breakthrough. Before that breakthrough/enlightenment, I couldn’t see my life without substances. They were my pillars.

First Nations people are underrepresented in the media. What do you hope to bring as a representative of your community in the music industry? Who are other First Nations artists and creatives who you look up to and are inspired by?

I really hope to voice the stories of our people because for many years, I never spoke of my culture. I grew up in a very close-minded small town outside of Winnipeg that was very racially divided. My mother wanted us to stay away from city gangs and other “demonic entities,” so we moved a lot. Many schools I attended were filled with racist rural communities, and I got into a lot of fights for simply being First Nations. After a while I gave up and stopped saying I was First Nations. That feeling stayed with me and is still in the back of my mind. Now that I have a platform, I feel a certain obligation to share our stories. Reconciliation, to me, means that each side needs to hear the other’s dark truths to fully sympathize and want change for one another. MMIWM (missing and murdered indigenous women and men) and residential schools are very close to my heart and have affected my entire family. It brings me joy to educate the residents of Turtle Island on their first peoples or, at least, share my families experiences.

In my teens, I didn’t really have many indigenous artists who I looked up to. To be honest, I didn’t know of any contemporary artists, but as a child, my life was rich with music. My grandmother and uncles all played bluegrass on the reserve. I didn’t know how to play at that time, but after forming a new relationship with my father in my early teens, he bought me a guitar and told me stories of his bands and what he wrote about back in his day. So my only real indigenous artist I looked up to was my dad. We’d stay up late watching movies, and he’d tell me stories of how dedicated he was to the guitar and taught me that one day my guitar would be my best friend. He’d say, “Danny, treat your guitar with respect. It’ll be your best friend, it’ll never walk out on you, it’ll never yell at you, and it’ll be around for as long as you keep caring for it.” Now when I’m looking for inspiration, I think of my dad (noosan).