Mystery is inherent in Robbie Basho’s music. His vocal performances extolled the wonders of both the natural and supernatural worlds. His playing could take you to places that don’t exist and make them hyperreal. Songs Of The Great Wonder, a collection of music that was lost in the vaults for 48 years, contains some splendid examples of both.

During the 1960s, Basho made a string of records for the Takoma label, which was founded by John Fahey. Both men played acoustic guitar and came up on the East Coast folk scene before moving to California. But while each musician made essentially solitary music that used sound and words to externalize the convolutions of their idiosyncratic psyches, they were profoundly different. Fahey’s ingenious instrumentals linked blues and bluegrass techniques to classical compositional ideas, and he often accompanied them with manifestly absurd liner notes that contained critiques of his social circle and the world at large. Basho’s music synthesized gleanings from and imaginations of music from other cultures to realize an escape from that same world into a realm of transcendent wonder, whose dimensions were made explicit by spectacularly supple vocalizations. Then and now, the only singer who matches his vocal athleticism and self-cultivated exotic aura is late Peruvian chanteuse Yma Sumac.

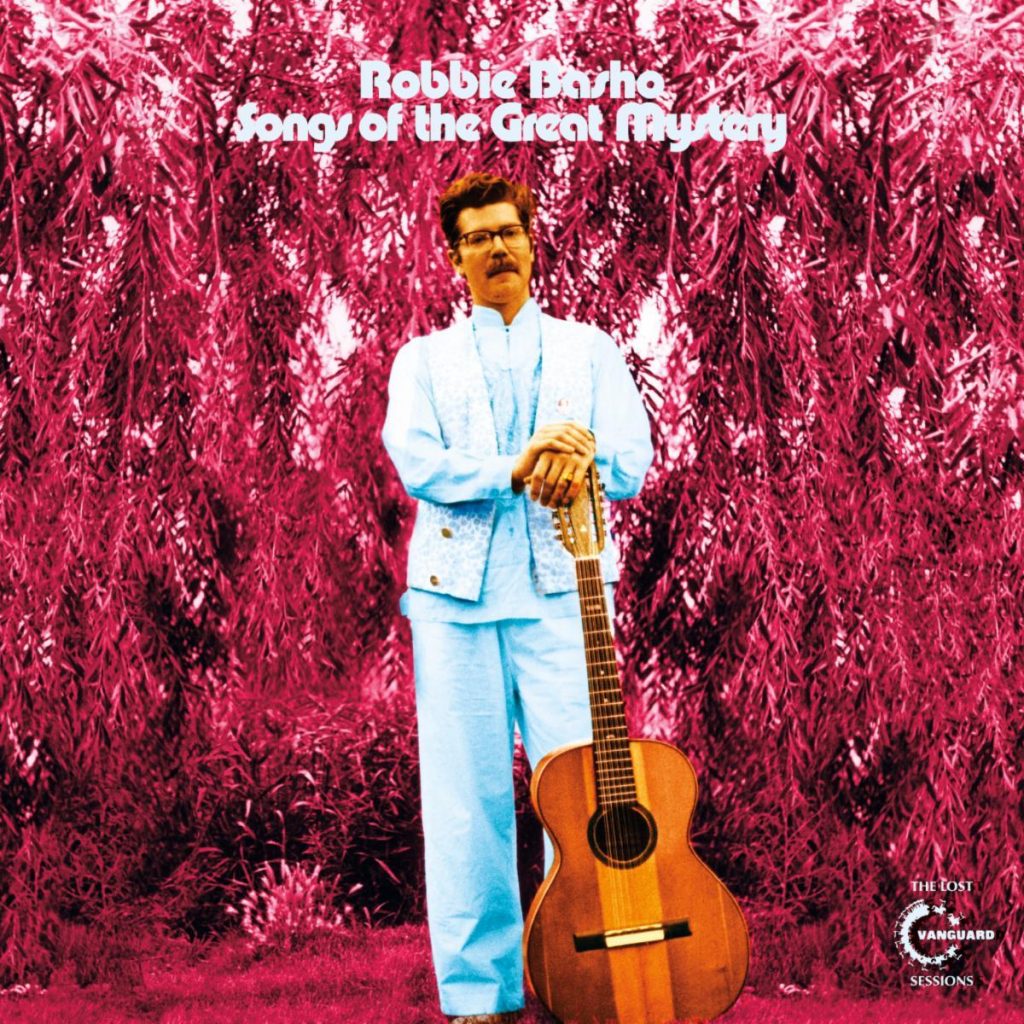

In 1972, Basho signed with Vanguard, the top dog of American folk music, and headed into the studio, ready to produce. In four days, he recorded two albums, Zarthus and Voice Of The Eagle, which celebrated his twin spiritual inspirations: the mystic Meher Baba and Native American culture. That session also included enough music for a third album, but since Vanguard didn’t shift many units of the first two, it stayed on the shelf until its discovery during an effort to digitize the label’s archive in 2009. But these tracks weren’t mere leftovers; annotator Glenn Jones’ scrupulously researched notes describe how revised and re-recorded versions of the material showed up on the remaining records that Basho made between his parting of ways with Vanguard and his death by medical mishap in 1986.

Songs Of The Great Wonder begins and ends with versions of “A Day In The Life Of Lemuria.” Both find Basho on piano instead of his usual guitar, whistling a poignant theme over a rolling keyboard vista that feels closer contemporary work by spiritual jazz artists Alice Coltrane and Don Cherry than any of his Takoma peers. The songs that follow are widescreen epics of imagined nobility. “Butterfly Of Wonder” may get the geographic particulars of the Monarch butterfly’s migration wrong, but it renders the arduousness of the journey in vividly romantic detail. “Kateri Takewitha” dramatizes the story of a Mohawk princess who became a Catholic saint. And a sequence of songs with the word “thunder” celebrates the wildness of weather with untrammeled vocal gymnastics. On these songs, Basho’s guitar is like a Hollywood orchestra, using galloping tempos and rich tonal colors to dramatize his tales. But for fans of his unadulterated picking, there’s the title tune, a winding, multi-sectioned piece that showcases the technical rigor necessary to express rhapsodic sentiments.

2020 is a good time to be a Robbie Basho fan. Filmmaker Liam Baker’s 2015 portrait, Voice Of The Eagle: The Enigma Of Robbie Basho, was recently released on DVD with hours of extra footage, and a boxed set of material that was extracted from storage during the movie’s making is planned for release by Tompkins Square after the COVID-19 epidemic takes its heavy foot off the brakes. But while Songs Of The Great Mystery is narrower in scope than those efforts, it’s no less essential. [Real Gone Music]

—Bill Meyer