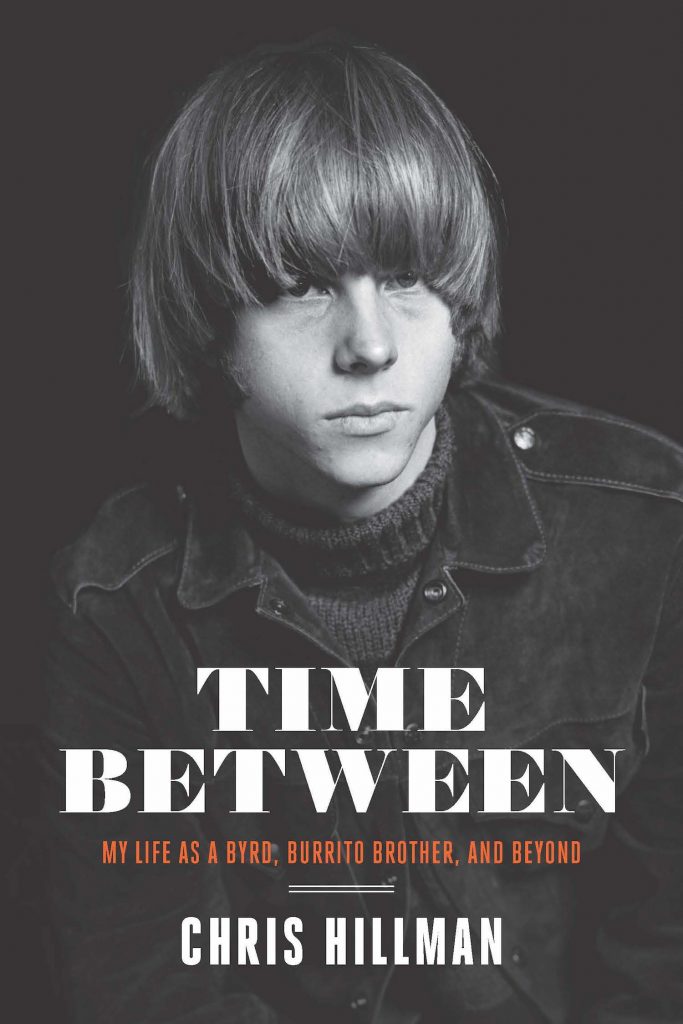

Singer, songwriter, bassist, mandolin/guitar player. Chris Hillman has worn many hats in his long musical career as a solo artist and as a member of the Byrds, Flying Burrito Brothers, Manassas and the Desert Rose Band. Now, Hillman is telling the story of those years in his upcoming autobiography, Time Between: My Life As A Byrd, Burrito Brother, And Beyond (out November 17 on BMG Books). “As far as the book goes, I tried to write it like I was having a conversation,” says Hillman. “Concise and honest.”

MAGNET had its own concise and honest conversation with Hillman, during which he spoke about his iconic work with the Byrds, surfing, John Coltrane and lots more.

I really enjoyed Time Between. It’s very honest. First off, let me ask how you’re doing. You open your book talking about the wildfires in California in 2017 and having to flee your home. Of course, there are terrible fires all along the West Coast right now.

I’ve been haunted by fires my entire life in this state. I’m third-generation Californian, but it’s not bothering us. It’s more Northern California based. This is our hurricanes or tornadoes or whatever. Of course, we do have earthquakes, too, and you don’t know when they’re coming. They just happen.

The pandemic makes looking ahead difficult, and your book is obviously a look back on your career. But I wanted to ask if we might get some new Chris Hillman music in 2021 or another tour with Herb Pederson. You’ve said making your 2017 album (the Tom Petty-produced Bidin‘ My Time) was a bit of good timing.

Well, this month I would have been on the road with Herb and John Jorgenson (both of the Desert Rose Band) and promoting the book and doing some stories-and-songs type of shows, and it’s all been moved to March. Actually, we are on the road in January in Florida. So, God willing, those will happen, but it’s day to day. You just don’t know, and as far as an album, I really don’t know. I’m not thinking that way. The whole thing with Tom Petty came along, but I wasn’t even thinking about doing an album. So that’s another situation, but I don’t know. Right now, I’m just enjoying being home, I’m going to be honest with you. And come January, hopefully, we’ll be doing some shows in Florida, and then we really get going in March and start working more around the country and stuff. So, we’ll see what happens. Me and nine million other guys who have far bigger tours booked—and every other business, it’s not just the live music business; it’s everything. So, hopefully, we will all be back to a normal situation soon.

In the book, you discuss getting hit by that first blast of rock ‘n’ roll in the mid-1950s but then discovering both folk music and also the bluegrass of artists like Flatt & Scruggs and Bill Monroe. My lazy assessment is that you ended up liking the “Blue Moon Of Kentucky” side of Elvis’ first single more than “That’s All Right.” Is that fair?

Yeah, that’s great—absolutely right. But, of course, for him to take that song and do it was amazing, as was all that early stuff where he was so brilliant. Brilliant, brilliant artist for that particular time period. But to go and cut “Blue Moon Of Kentucky,” that was a big one for Bill Monroe—he did quite well on that one as a songwriter. Although the other guys in the Byrds were not as involved in bluegrass music as I was, they certainly were aware of it. And, of course, as I’ve said repeatedly in the book, we were never a garage-rock band. We were folk guys, and that’s where Roger (McGuinn) came from … David (Crosby), Gene (Clark), everybody. Mike (Clarke) was the only one that really didn’t come out of that area of being a folk musician. So, bluegrass falls into that category.

You were a surfing kid growing up around San Diego, but it doesn’t seem like you ever got into surf music. Was it just not your thing?

It’s funny. I liked it—“Walk, Don’t Run” and all that. I really loved it, but when I was surfing in high school, I would hang out with guys older than me who were already in college who were surfers. But they didn’t listen to Jan & Dean and the Beach Boys. This is, like, 1960, 1961. They were listening to Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf. I would go to their parties. That’s when I was starting to learn how to play guitar, and my friend John and I would play these parties. And these guys were all in their 20s, and we were like 16 or 17, and they would make sure we had lots of beer, and we’d play, and it was great. But real surfers—hard-core surfers—never listened to surf music.

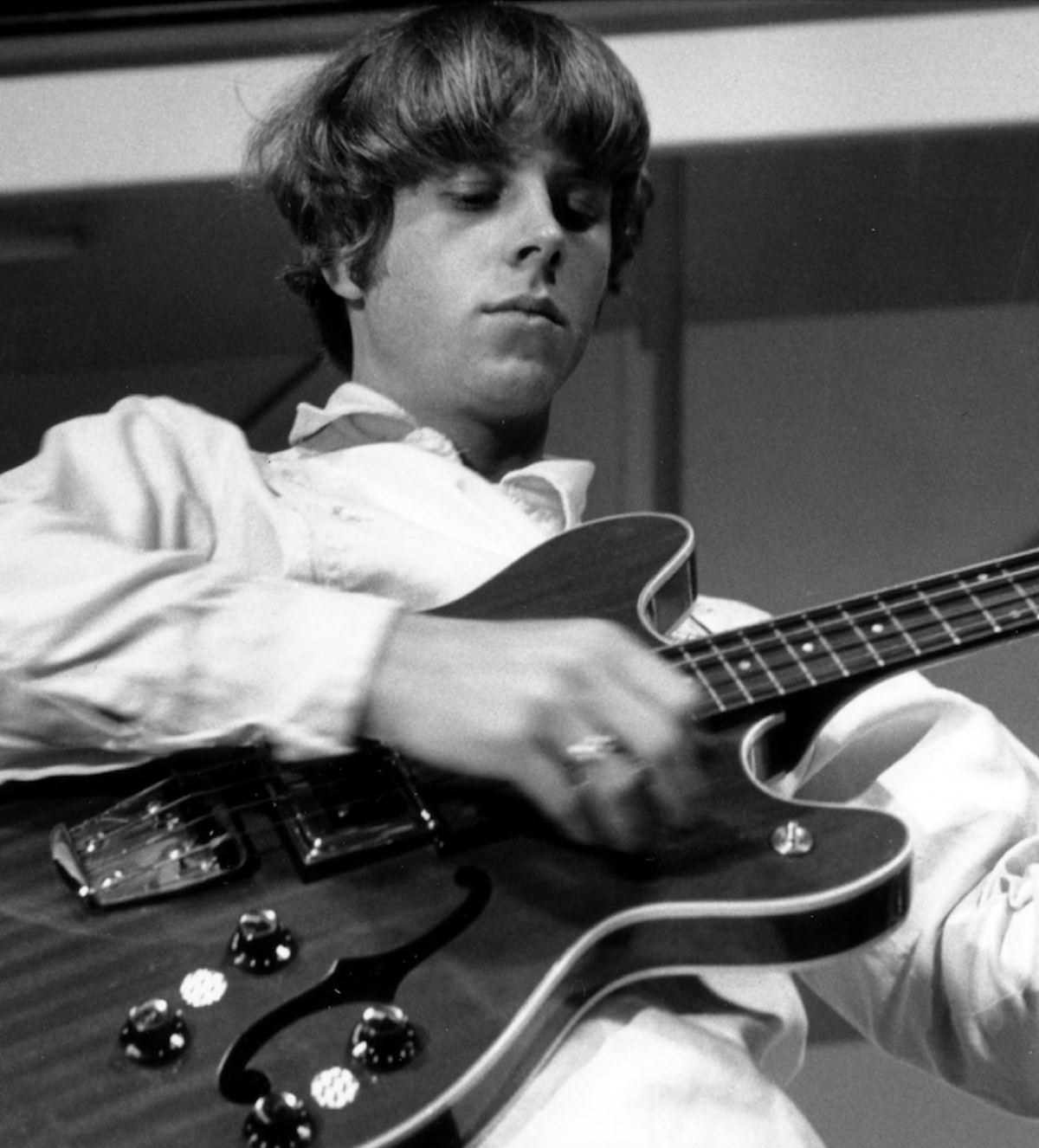

In the Byrds, you had to transition from the mandolin you’d been playing with bluegrass bands to bass, and you and drummer Michael Clarke had to essentially learn on the job.

I think all of us did with the exception of McGuinn. David, he was a good player. Gene was OK. But Mike and I really did. I think we both probably used the same method and said, “Oh, yeah, we can play.” We learned, we learned quick. But that was the beauty of it. Because we didn’t have a blueprint, we created our own style individually, and it melded together so well in the Byrds. The five of us just worked so well.

I wanted to ask how you came up with that thunderous, apocalyptic bass intro to “Eight Miles High.” I’ve read about how Gene, Roger and David wrote the song and the John Coltrane influence, but nothing about your bass part. It’s there on the early RCA version you guys did in December 1965. It’s simple yet effective. How did you work it out?

It’s really a take on the Coltrane record A Love Supreme where he’s chanting, “A love supreme, a love supreme,” and that was part of where I got that idea, “Bom-bom-bom-bom-ba-da-bom.” I don’t think anybody said, “Hey, Chris, kick off the song with a bass thing.” I don’t remember anybody saying that. They could have. Somehow, I just started playing it, and we fell into it. But, I knew this jazz player, Leroy Vinnegar, and he was backing up Judy Collins when I met him at a folk festival in Hawaii. Years later I see him in a documentary and he goes, “Yeah, I’m working on a new song,” and he’s playing my bass line. This was after “Eight Miles High” came out. I was quite complimented by that. He was a really good, schooled jazz player. That’s the best stamp of approval.

Other than TV appearances, there’s little in the way of live 1965 or 1966 Byrds recordings. It’s a shame for fans today. I think I read somewhere that the record company wanted to do a live album, but that your manager, Jim Dickson, declined. Is that true?

I don’t remember that being discussed. We could have done it; we could have pulled it off. There’s so much stuff out there. If you had said, “Why did you write this book?” I really felt I had read so many inaccurate things about the Byrds and the Burrito Brothers, and that was part of why I wanted to write the book. I don’t recall us discussing doing a live album. But, I will bring that up with Roger McGuinn when I talk to him during our weekly Trivial Pursuit game! Taking place from his place in Florida and mine in California.

You really blossomed as a songwriter on (1967’s) Younger Than Yesterday. I hear hints of Rubber Soul Beatles in songs like “Have You Seen Her Face” and “Thoughts And Words.” In the book, you talk about being inspired after participating in a recording session with (South African trumpeter) Hugh Masekela. I wonder why that session sparked your songwriting.

Something happened! I don’t know. I think I was having so much fun that was so out of the element of the Byrds experience. Completely different music. Something was unleashed, and I just came home and started goofing around and came out with a song, and I was on a kick for the rest of the week.

Younger Than Yesterday, to me, has a cohesiveness like the first one (1965’s Mr. Tambourine Man). It just hangs together.

I’m with you. I like Younger Than Yesterday beyond what I contributed. “Renaissance Fair,” the stuff David did was really good. And the first album, I’m right with you. I love that. I’ve had people to this day say, “Well, you guys didn’t play on the first album.” Well, I say, “Really? Listen to it again. That’s us playing.” You can listen to the “Mr. Tambourine Man” cut and you know that’s studio session guys—it’s so slick, and it’s good! It got us through the door and got us going. But the first album, I love the songs. I love how we approached everything. “The Bells Of Rhymney,” of course, being one of my all-time favorite songs we ever did. That captured the Byrds’ essence perfectly. From the vocals down to the playing. I loved Gene’s stuff on the first album. He was such a good, prolific songwriter. Even at the end with McGuinn, Clark and Hillman, he had some incredible songs on those albums. The Byrds, like I said, we just didn’t grow up playing in a garage—we came from other areas, but somehow it all came together quite well.

The recordings you did in 1964 at World Pacific Studios were kind of your Hamburg Beatles experience, your woodshedding days.

That’s correct. And we had the opportunity to go in there for hours and get out of there at two or three in the morning. Taping everything on a two-track machine. It was the greatest to be able to listen back and say, “Let’s fix that.” And it wasn’t cutting things for future releases, although that did happen, but it was mostly practice stuff. We did get that long run at Ciro’s in L.A. to hone the music doing two, three, four sets a night. So that helped.

Elton John, Bernie Taupin

The first Flying Burrito Brothers album (1969’s The Gilded Palace Of Sin) has consistently good songs like the first Byrds album. There’s a cohesiveness to it that’s not there on the second. Is it fair to say Gram Parsons could’ve used the advice Jim Dickson gave you early on to make records you could be proud of in 40 years?

The problem was lack of a focused work ethic. Gram knew good songs, and he had that ear for them—he just didn’t put the time into it. The second album was not real good. There’s not really any moments on that one. The first album is good. Sonically, I don’t like the way it sounds. The songs are good, and the songs hold up. Like “Sin City” and “Christine’s Tune,” both of them covered so many times, from Dwight Yoakam to Emmylou Harris to Beck. And that’s great. If you’re taking all those West Coast, country-rock bands, the Burritos had the songs. But we didn’t have the cohesiveness, the tightness of a musical act. I went from playing “Eight Miles High” to the Burrito Brothers, and it was like starting over. Our execution was very poor. I wish we could’ve done that a little better, but that’s water downstream at this point. The third Burrito Brothers album (1970’s The Flying Burrito Bros) with (guitarist/vocalist) Rick Roberts was good; it was different. And the live album is one of my favorites, (1972’s) Last Of The Red Hot Burritos. Smokin’. It captured everything—country, rock, bluegrass—on that live album.

You’ve played with some iconic bands in your career. Can I ask if you have a favorite? Or is that like asking a parents about their kids?

They were all great. There were moments in all of them. The Byrds were probably the most prestigious group I was ever in. The Desert Rose Band was a great band because, consistently, onstage for performances, we were in the 90th percentile—that’s how good it was. We had no baggage. No problems. And they were a bunch of great guys to the point where we said, “OK, we’re done.” We were having trouble getting on the radio. So we parted company after a long run. I was in that thing for seven, eight years, and we remained friends. Obviously, I still work with John and Herb, and we’re going on the road, hopefully, in Florida in January and then March. And, of course, I worked with Roger a year and a half ago. That’s the best part—we continue the relationship. I don’t have a favorite really. I guess the Desert Rose Band in that I’d assumed a leadership role.

—Bruce Fagerstrom