MAGNET’s Mitch Myers explores the historical rapport of Allen Ginsberg and Harry Smith, the cosmic riddle of their First Blues, subliminal conspirator Bob Dylan and other beat coincidences.

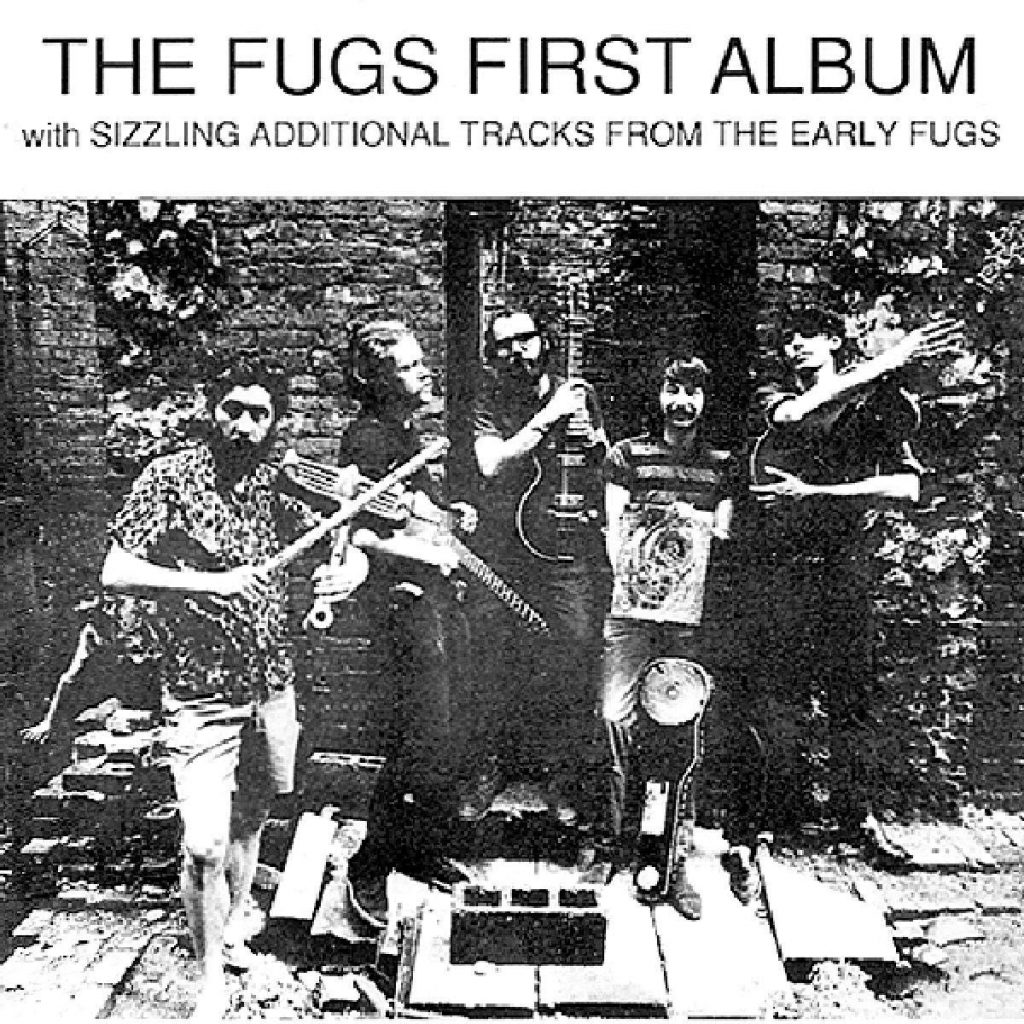

Were prophecies evoked when the Fugs sang, “Village Voice nothing, New Yorker nothing, Sing Out! and Folkways nothing, Harry Smith and Allen Ginsberg, nothing, nothing, nothing?” The song “Nothing” was found on The Fugs First Album, produced by Harry Smith in 1965, nearly a decade before Ginsberg and Smith combined their own talents for an impromptu—or was it planned?—recording session at the Chelsea Hotel, resulting in Ginsberg’s album, First Blues: Rags, Ballads And Harmonium Songs.

So then, might First Blues be a representation of the existential nothing? Or is it really something?

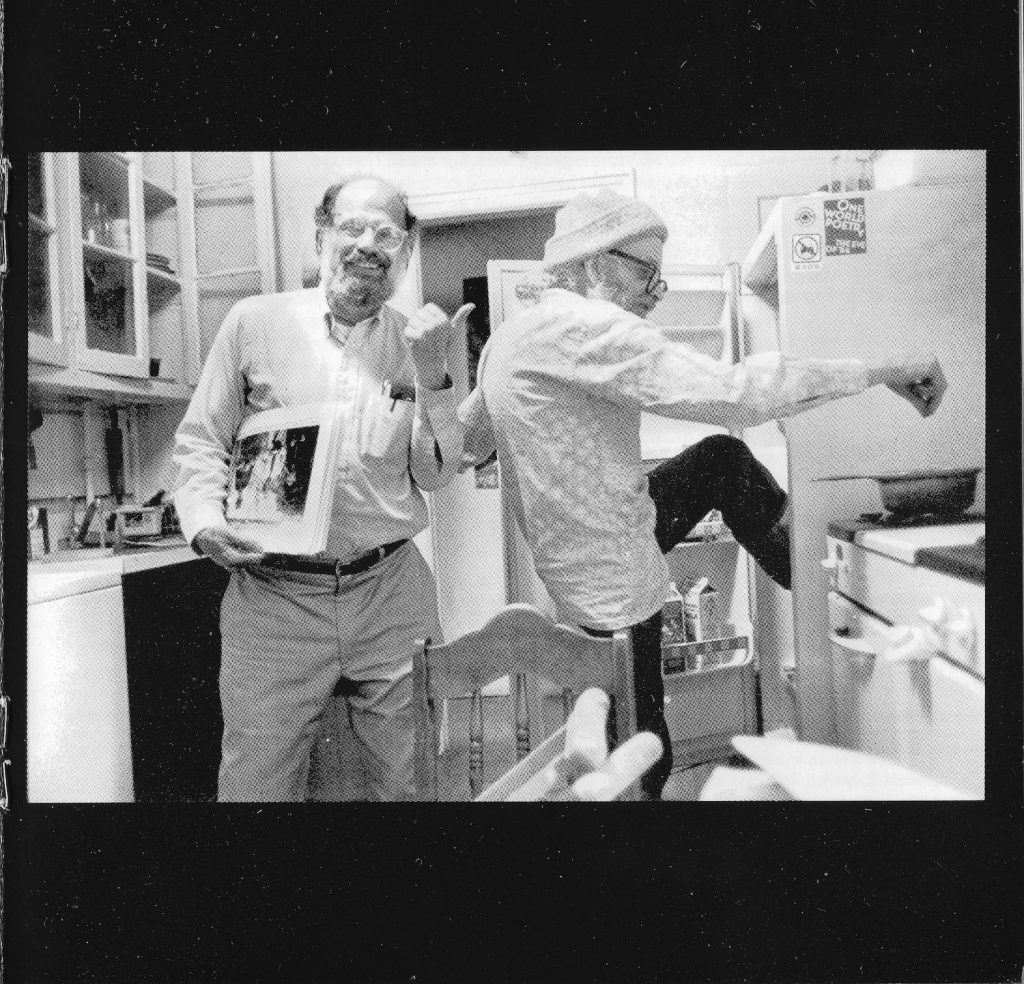

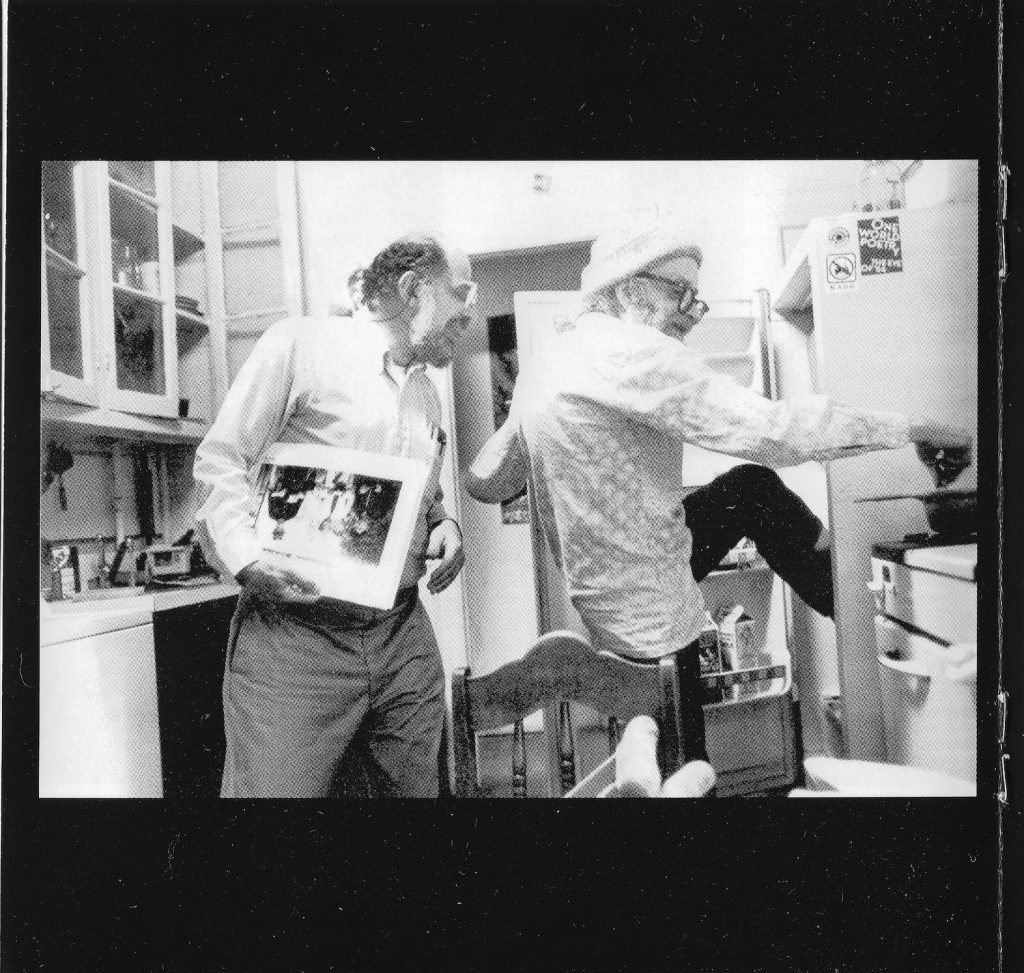

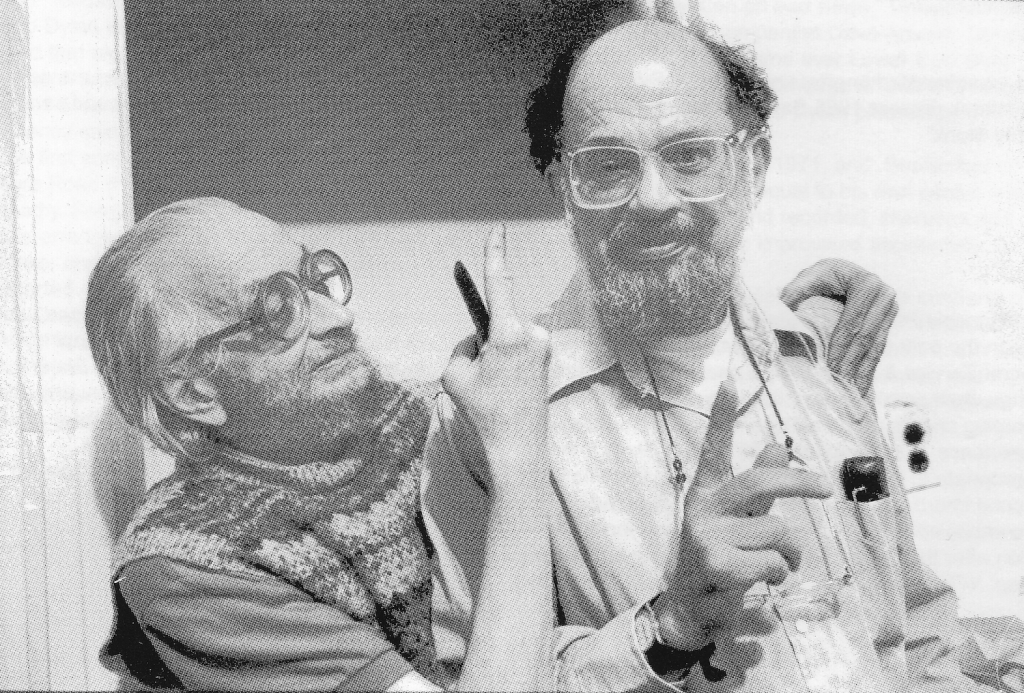

Harry Everett Smith met Irwin Allen Ginsberg in 1959 at The Five Spot in New York City, where jazz pianist Thelonious Monk was enjoying one of his residencies. Ginsberg had only heard of Smith, but recognized him immediately. Smith was sitting at a table, transcribing Monk’s angular melodies into impressionistic drawings. Allen would later describe his first vision of Harry as “slightly hunchback, short, magical-looking, in a funny way gnomish or dwarfish, same time dignified.”

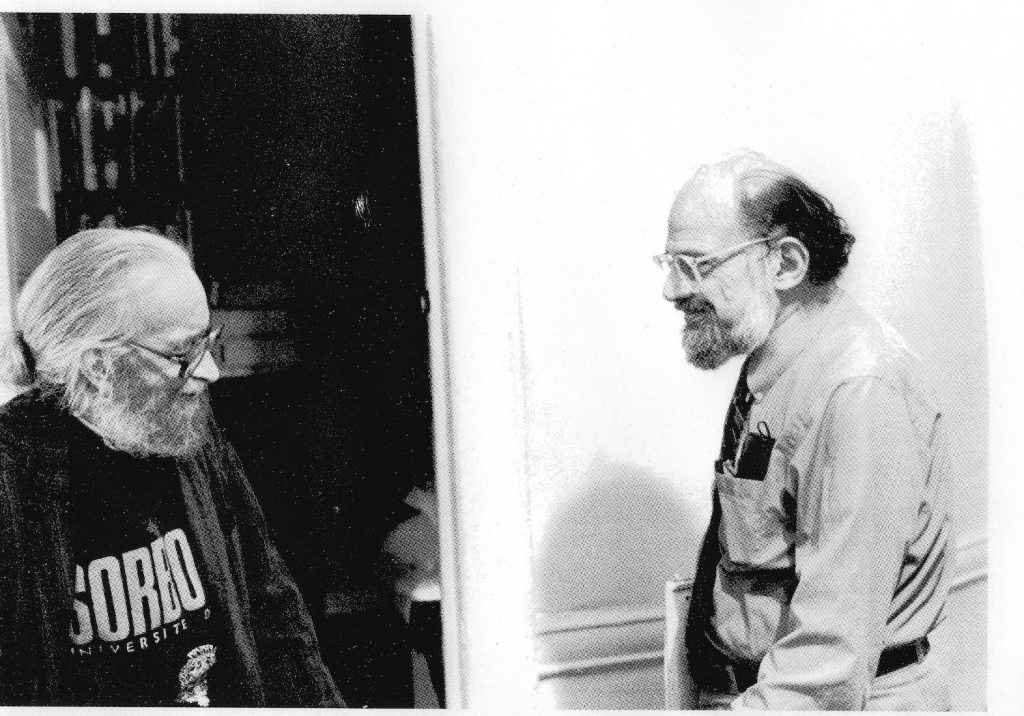

A chance meeting? Not necessarily, considering the synchronistic weltanschauung when it comes to all things Harry Smith. And just how much empyrean nonsense is it to contend that these two men were opposites who did indeed attract? Surely they couldn’t have come from more contrasting orientations. One, a hermetic, neo-celibate whitebread record collector/visual artist from Oregon with roots in freemasonry and an attraction to occultisms. The other, a free-loving gay Buddhist Jew from New Jersey who became reigning ambassador of the beat generation and a poet of Whitman-esque proportions.

Smith was a cultural obeah man who lived on skid row in small rooms with stacks of books and small, dead animals in the freezer. Ginsberg was an exhibitionistic showman who, according to historian Harvey Kubernik, “was a tireless self-promoter who would show up for the opening of an envelope.”

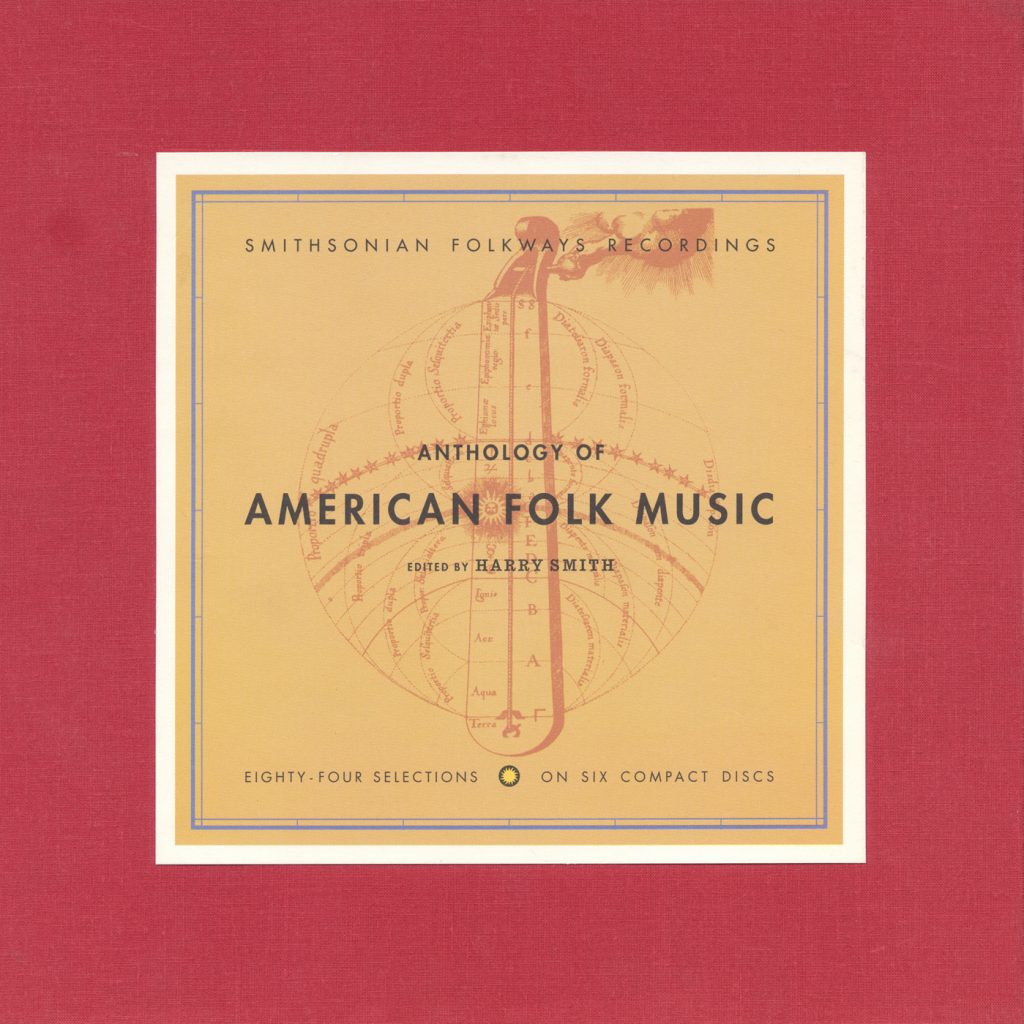

Although their talents differed, both men had an impact on the expanding of consciousness in the 20th century. Along with Messrs. Kerouac and Burroughs, Ginsberg contributed to a generative unshackling of prose and poetry while his libertine lifestyle ran against the grain of the intellectual establishment. His countercultural stance encompassed drug and sexual experimentation, political dissidence, gay-rights activism and antiwar protests. Ginsberg’s epic poems “Howl” and “Kaddish” fueled the imaginations of generations. For his part, Harry Smith enriched the realms of film, visual art and anthropology in numerous settings. His annotated compendium of rural song traditions, The Anthology Of American Folk Music (first released in 1952), rescued an entire canon of aural/oral expression on the verge of disappearing, and had an immeasurable influence on greater musical appreciation in the modern world.

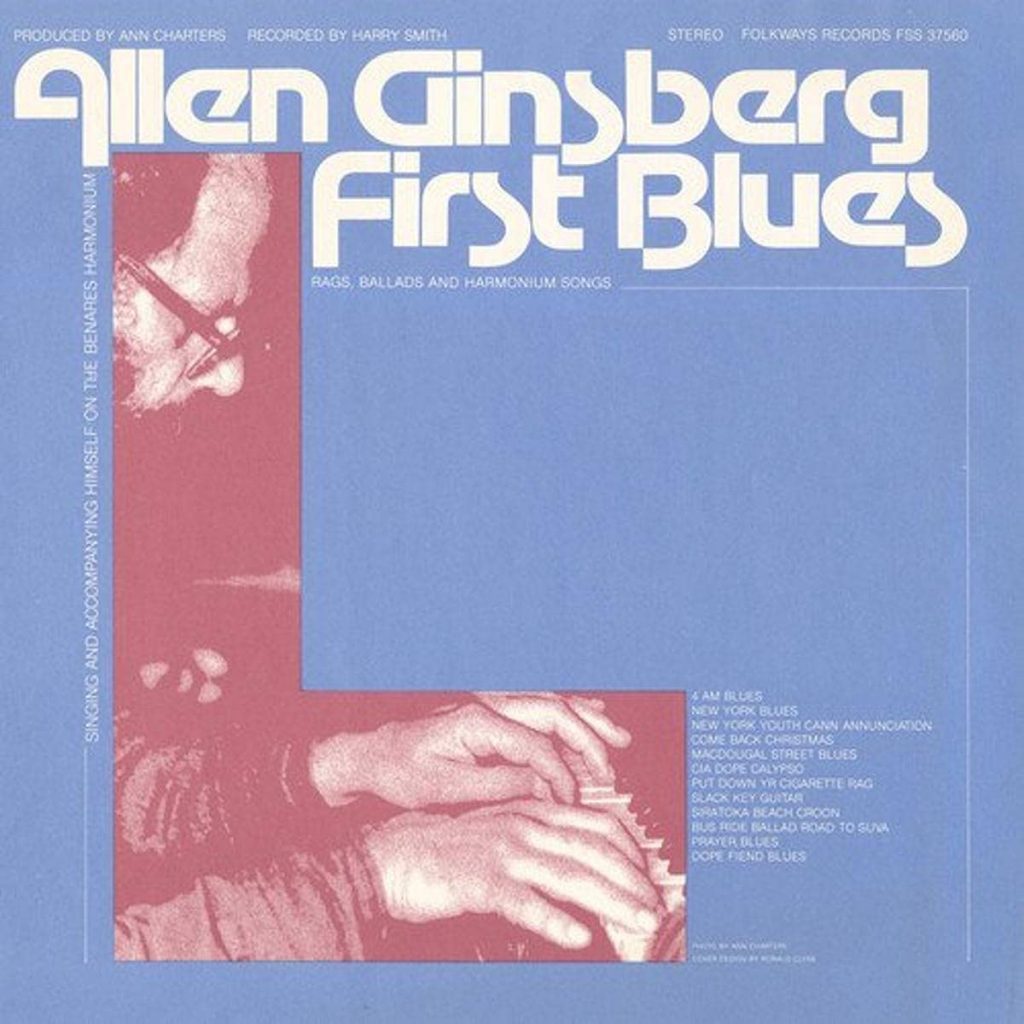

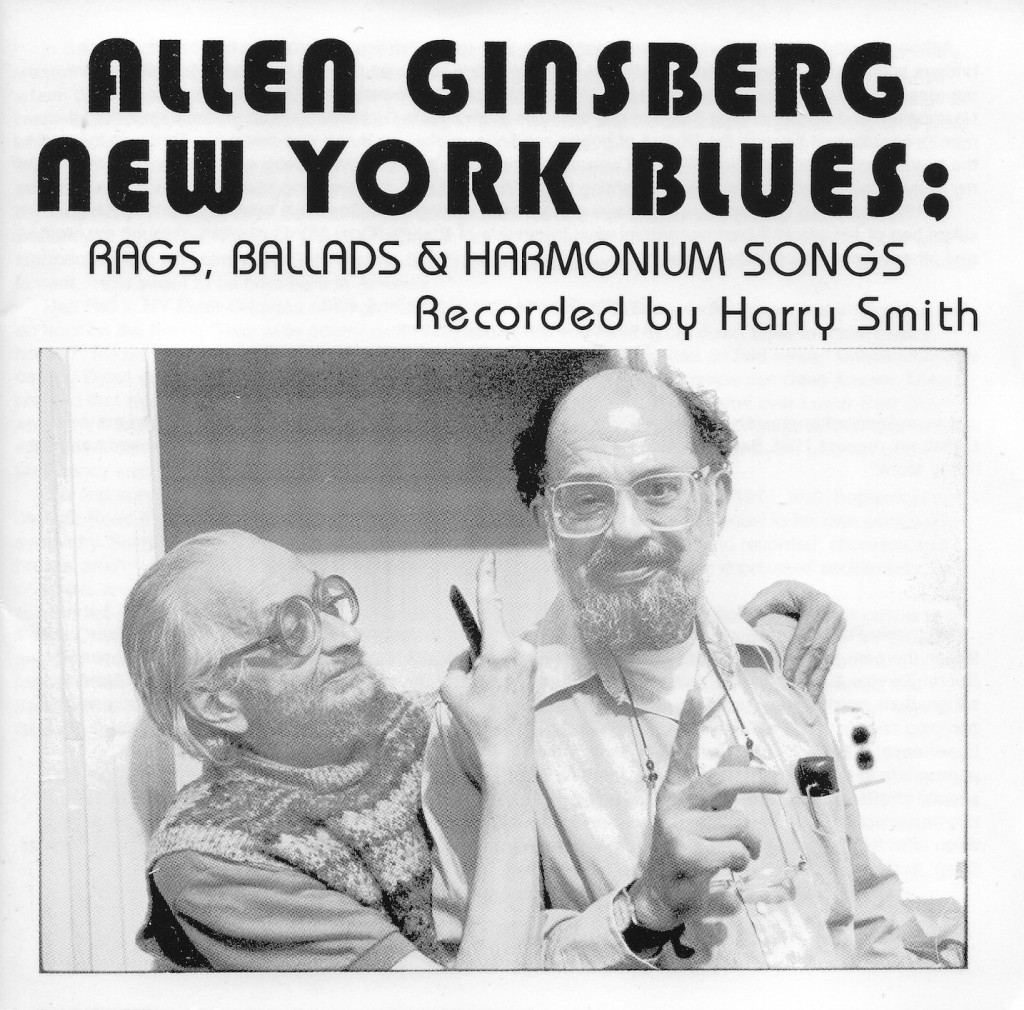

First Blues: Rags, Ballads And Harmonium Songs is a folk-form cryptogram of sorts, with connections, implications and historical significance that defy simple assessment. Considering the mystique, the confusion and the interconnectivity of these beat/archival coincidences, it must be said that there are actually two First Blues records. Both were recorded in the 1970s and released almost simultaneously in the early 1980s. The Ginsberg/Smith session at the Chelsea was compiled/produced by beat biographer Ann Charters and released on Moe Ash’s Folkways label.

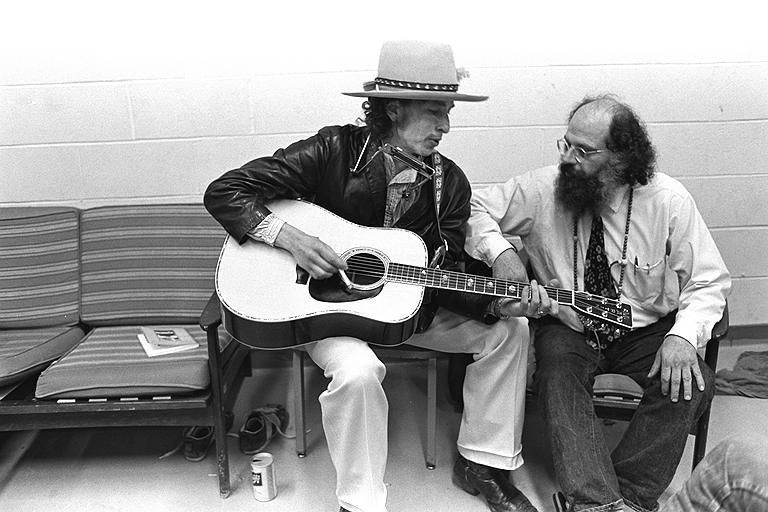

Columbia Records impresario John Hammond produced the other First Blues. It was released on Hammond’s (short-lived) JHR record label instead of Columbia, which considered the album too flamboyant. Unlike Ginsberg’s solo performances on the Folkways LP, the Hammond album features the poet flush with accompaniment. Musicians like David Amram and Happy Traum participated, as well as Ginsberg’s lover Peter Orlovsky and a man wryly credited as Blind Boy Grunt (Bob Dylan). Although some of Ginsberg’s compositions appear on both collections, the two albums are as different as Harry Smith and John Hammond.

When I discussed First Blues: Rags, Ballads And Harmonium Songs with late record producer Hal Willner, he wondered, “Was it a conscious decision to record in Harry’s room at the Chelsea for environment as opposed to Allen’s? [There is] kind of a tense atmosphere, and Allen doesn’t sound all that relaxed.” True enough, singing his idiosyncratic blues while playing a small hand-pumped harmonium from Benares, India, Allen soldiered through the Chelsea performances unadorned by conventional musicality.

But if Ginsberg really is the sole performer, the lonesome entertainer, the solo-ballad-blues-disciple, why does Harry Smith loom large in the proceedings? Practically speaking, Smith’s documentation of Ginsberg at the Chelsea isn’t any different than his other fieldwork, like his 1965 recording of peyote rituals by the Kiowa Indians in rural Oklahoma. (See Conrad Rooks’ film, Chappaqua for additional clues.)

And what of the eternal Bob Dylan? Ginsberg truly loved Bob, and was eager to impress him. “I don’t think I would have been singing if it wasn’t for younger Dylan,” Ginsberg told Kubernik. “He turned me on to actual singing. Dylan’s words were so beautiful. The first time I heard them I wept.” Not only did Dylan inspire Ginsberg with his words (and fame), but Bob also showed him the three chords he would need to write a folk or blues song, insisting it was Allen’s time to sing out rather than recite his prose.

So, while Harry was Allen’s towering twin of aesthetic strength, Dylan figures into First Blues as a subliminal conspirator. While Dylan repaid his artistic debts to Ginsberg by encouraging the poet to sing, there’s a less obvious connection between Dylan and Smith. That is, Dylan’s first album contained several songs found on The Anthology Of American Folk Music. And if young Dylan gained insight into America’s earliest folk/blues phenomenon while listening to the Anthology, then Bob made his overdue back payment to Smith via First Blues. Dylan wasn’t on the album, but he appeared on the Hammond-produced First Blues, further illuminating the extended relatedness between himself and mentors Ginsberg, Smith and Hammond.

But what does all this say about Harry Smith recording Allen Ginsberg on that particular day? “It was just another example of field anthropology in a post-modern mode,” claimed Ed Sanders, author and co-founder of the Fugs. “Allen always rose to the occasion of spontaneity; this was one short slice of 20th century existence. Two geniuses colliding at the Chelsea Hotel in 1973.” Sanders’ perspective certainly goes along with Ginsberg’s own favored adage, “First thought, best thought.”

Ginsberg’s eccentric performance would have been forgotten and lost forever were it not for Smith’s predilection for recording folk art, as well documenting everyday life. Late Fug co-founder Tuli Kupferberg had an even more speculative assessment of the infamous Chelsea encounter: “When two geniuses get together, you’ve got to expect something great! … Is there music on it?”

Following this raw musical phase, Ginsberg chose to perform in more conventional contexts. Steven Taylor played guitar with the Fugs and he was Ginsberg’s accompanist for years, even playing on one of Hammond’s First Blues sessions. Taylor reflected on Ginsberg’s “blue” period in the early ‘70s and explained, “Blues is a particular genre within a larger history of African-American folk music. One of Allen’s main inspirations was Lead Belly, who was on the radio when he was a kid. Lead Belly is generally considered to be a songster, not a bluesman. Blues could be part of his repertoire, but the songster is a larger tradition. Allen was more of a songster than a bluesman—a historian in song, a singer of ballad narratives and a singer of topical material.”

“Blues are a funny thing,” echoed Ed Sanders. “They are supposed to make you sad, but they make you triumph, too. Allen’s diaries are strangely filled with the down mode. The poor guy was so publicly joyous and exalted, but in his private moments he was quite sad and dejected. He was drawn to the blues. He had been a fan of Ma Rainey and ‘CC Rider’ was the final music, the last tune he listened to before he died.”

And what of the interconnectivity that Harry Smith brought to their First Blues project? Does it serve the same creative function Smith unleashed when he traced the paths of interrelated folk and blues idioms with his now-fabled Anthology?

John Feins studied under both Smith and Ginsberg at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colo. He maintained that Smith’s non-stop efforts to document sound were informed by a deep empathy for humankind. “What’s great is that Harry wasn’t an elitist, he recorded everybody,” said Feins. “Harry felt that every occasion of sound was a recordable event and it had not just artistic merit and meaning, but anthropological meaning. If a human being opened his mouth up for song, Harry treasured and honored it as an archivist and a scholar and an anthropologist. He captured it when he could.”

Just how well does First Blues hold up? Ginsberg authority Bob Rosenthal was tough but fair when he said, “I’ll be frank with you. I couldn’t listen to this record. I just wrote it off as caterwauling. I was so skeptical when I heard someone was going to reissue this. I’ll confess I’m much more interested in it now than I was at the time when it came out. Allen saw the possibility of helping to change people’s consciousness. And so did Harry, although they were total opposites in methodology.”

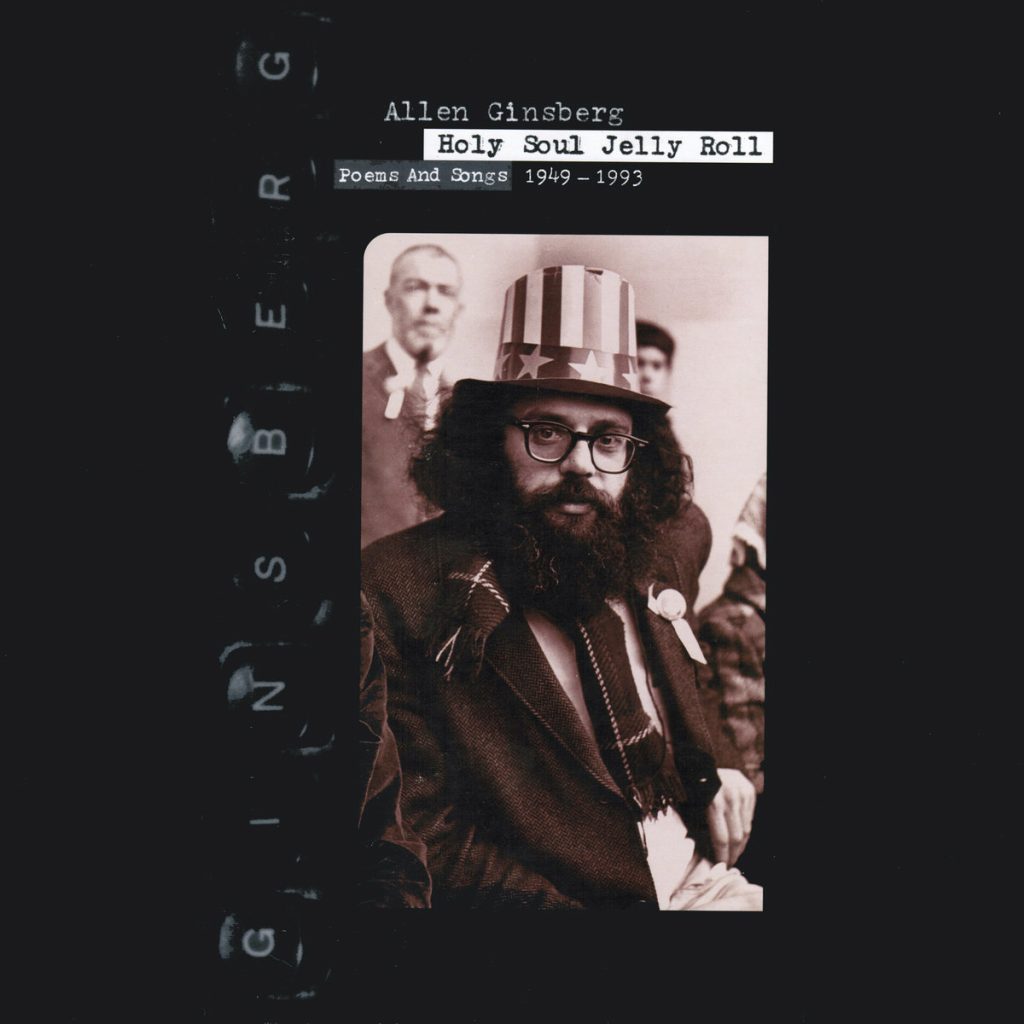

Hal Willner believed that First Blues was more than an archival curiosity, and he included some of the tracks on his curated Ginsberg anthology, Holy Soul Jelly Roll: Poems and Songs, 1949-1993. “I’ll admit when I first was slated to produce an album with Allen I was holding my ears,” said Willner. “Yet, it’s amazing how this stuff holds up and just gets better. I felt I needed it for the historical aspect—here’s Harry Smith producing Allen Ginsberg. But when I went back to those tapes, I couldn’t believe how strong it was.”

Were Ginsberg and Smith blue when they made these recordings? Were they stoned? Whatever the mood, Harry allowed himself to be subsumed by Allen’s Rags, Ballads And Harmonium Songs. As a witness to the birthing of Allen’s singing career, Smith showed his colleague patience and understanding, supplying Ginsberg’s ritualistic display at the Chelsea the dignity it deserved.

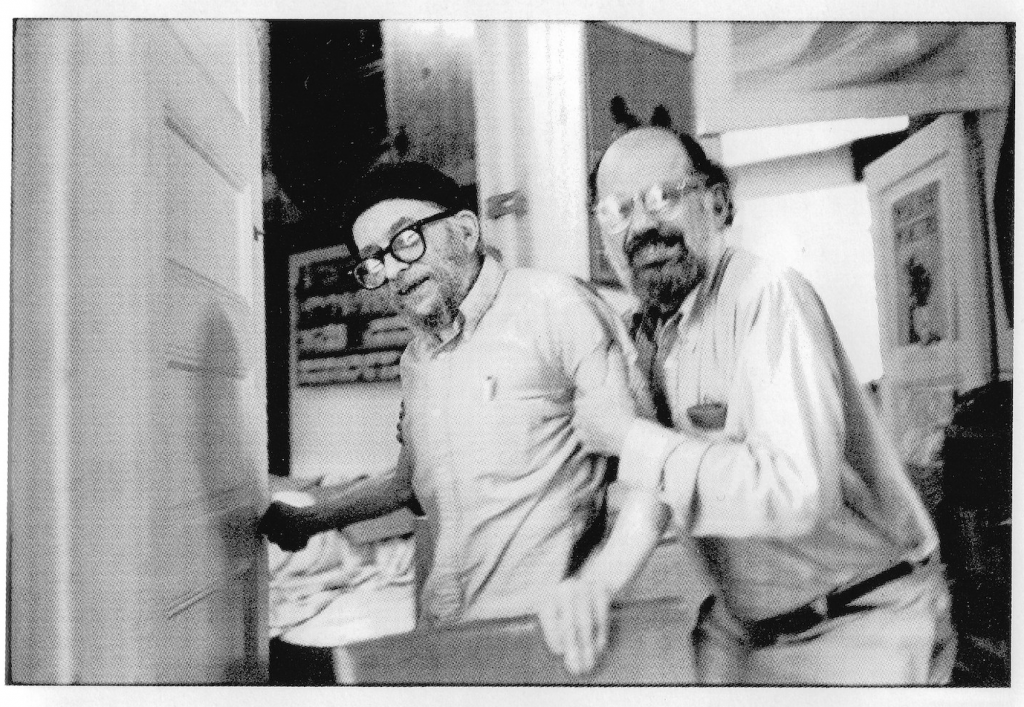

“The role of the documentarian is often restrictive because of the attention to detail, the mechanics or just removing your own ego,” said historian Kubernik. “To help govern the person you are recording, you go into a secondary position. Harry was willing to do it. He put himself below the title to benefit the attraction.”

According to Ginsberg, Smith disagreed with some of the choices Ann Charters made when editing this album for release. Why Smith was unable to complete the task himself is yet another cause for deliberation. Harry’s relationship with Folkways honcho Moe Asch was often strained over the years, but Asch did respect Smith’s archival efforts and used his contextual understanding of art and ceremony to great effect. And the final edit by Charters? It is what it is.

Like Smith, Ginsberg had an appetite for collecting things, and his own record collection reflected a deep love for music, especially the blues. “When you collect, you put disparate things together in relation with other things and you get new results from that,” said John Feins. “Harry loved to determine patterns in things. I think he derived meaning and insight from patterns that he saw in things that he collected or examined. Easter eggs, Indian rugs, paper airplanes—he would be interested in all the different forms and make great leaps of genius thanks to the juxtaposition and understanding of patterns and synchronicity and the overlapping of things.”

One thing is certain. We no longer ignore Harry Smith’s role as a cosmic documentarian. His preternatural musical tastes and hyper-informed critical judgments made him a cultural Nostradamus whose anticipatory discoveries and polymath predictions are still unfolding long after his death. Smith’s earnest contextual framework fueled Ginsberg’s gay-vaudevillian prose attack, transforming his poetic diatribes into semi-melodic riddles, verbal instructions, joyous celebrations and coherent protests, all captured in real time.

So, this is the meeting of two friends, one poet reborn and one great rememberer, who both found the ways and the means of making the extra-musical musical.

So much for nothing.

This piece was adapted from Mitch Myers’ 2007 book The Boy Who Cried Freebird, and the original essay was commissioned as liner notes for the 2002 reissue of First Blues.