MAGNET’s Mitch Myers relinquishes the remote control for a guided tour of the century where ragtime jazz, hippie rock and alternative Americana rule

I was watching the Anniversary News Channel the other night—it must have been Sunday since the segment was their weekly half-hour music rundown Quick Picks. I love the Anniversary Channel, and you remember their tagline: “All Anniversaries—All The Time.” They provide just the right amount of information, no matter how arcane the subject. Revolutions, performances, birthdays, deaths, sporting events, natural disasters, famous speeches, wars, inventions, headlines, scandals, TV shows, marriages—you name it, they got it covered. ANC’s nonstop retrospectivision regularly includes notable music moments, and they caught my attention with a sharp little thumbnail sketch on the 100th Anniversary of pianist James P. Johnson’s historic recordings from 1921.

It turns out, 100 years ago, James P. Johnson was an innovator whose piano style paved the way from stride and ragtime music toward genuine jazz. Johnson’s earliest compositions were preserved and distributed on player-piano rolls, and his performances infused the reigning ragtime stride with a blues sound in a uniquely swinging and modern way. His playing had progressed around the same time that phonograph records were first being introduced, abetted by the fact that record companies had finally realized the market for black (race) music was viable. A cogent, wry composer whose rags left room open for improvisation, Johnson mentored Harlem stride pianist Fats Waller and influenced jazz giants like Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk.

Anyway, in 1921, Johnson—whose name belongs up there with Scott Joplin and Jelly Roll Morton—released these four phonograph recordings on the Okeh Records label, including “Keep Off The Grass,” “Worried And Lonesome Blues,” “Harlem Strut” and, perhaps most famously, “Carolina Shout.” The performances were particularly auspicious because they featured some of the first jazz piano solos to ever appear on a phonograph record—ever. They say Waller and Ellington learned to play “Carolina Shout” by studying Johnson’s piano rolls and that performing the composition became a rite of passage for piano jazzers of a certain age.

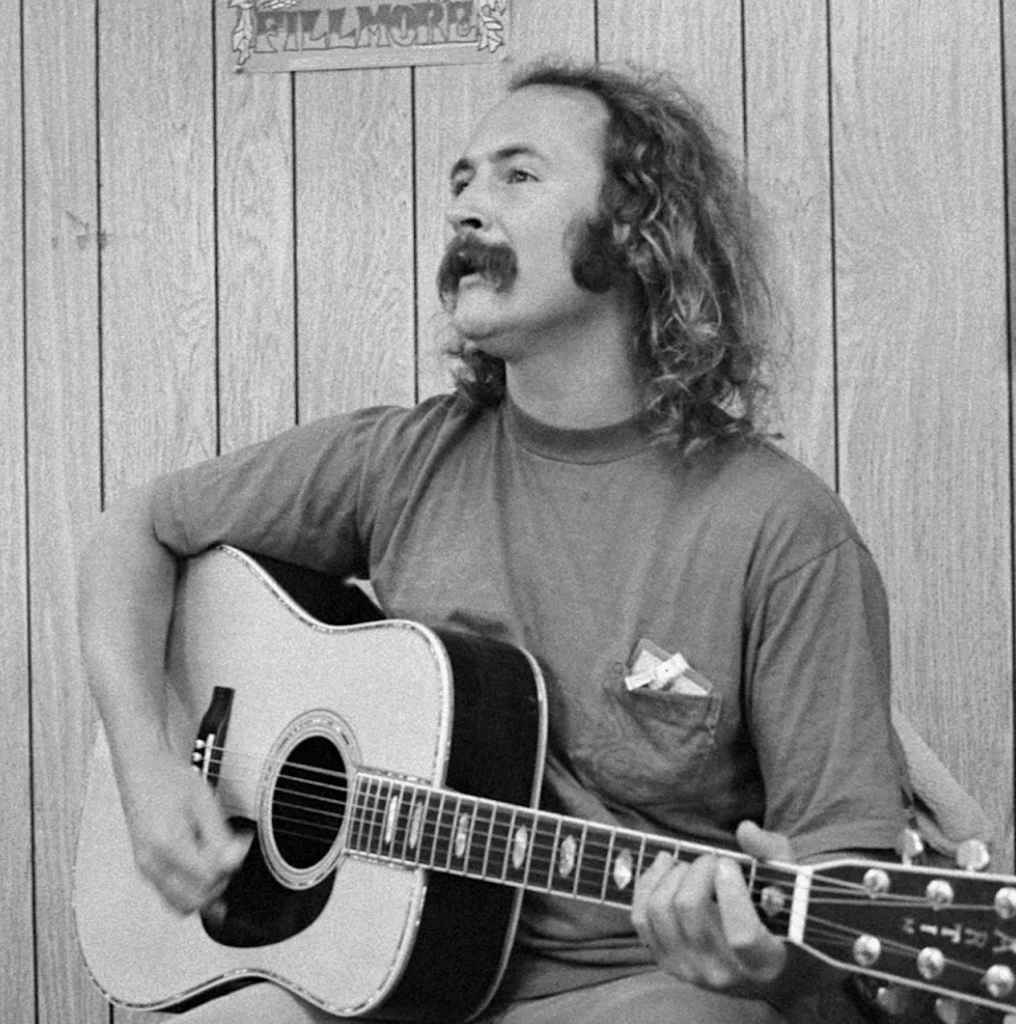

It was a satisfying time capsule of jazz nostalgia, so I was a little thrown when Quick Picks jumped from James P. Johnson to the 50th anniversary of David Crosby’s 1971 album, If Only I Could Remember My Name. A funny choice, but somebody over there at the ANC must have had fond memories, calling it the ultimate hippie record from a golden era of album rock. Apparently it was a summit of southern and northern California super-players, where members of the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Santana all came together with some other famous friends to help Crosby through an extremely dark period.

The Anniversary Channel went on to claim that the record was one of the finest solo albums found within the greater universe of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. Decidedly non-commercial, If Only I Could Remember My Name was an anachronism that somehow checked all the boxes—it was one of the most stoned LPs to come from the CSNY bunch and boasts an absolute peak in album production. The record arguably is the most self-indulgent and most personal from that particular clan of talented musicians—all of which is really saying something—as well as being Crosby’s own definitive shining hour.

The dream was over for Crosby in 1971—he just didn’t know it yet and still had his artistic momentum. His girlfriend had died in a car accident, CSNY had gone through its first of many breakups and his drug use was already well beyond control. Yet, Crosby’s overindulgence coupled with his stoned perfectionism, innate musicality and the stellar quality of his fellow musicians helped to create a beautiful, unified sonic masterpiece of sorts.

Crosby’s strength was singing harmony rather than being a lead vocalist, and that’s reflected in the album’s range, which delivers only two outright rockers. The balance includes wordless vocals, impassioned group singing, insular jams and instrumental interludes. These carefully crafted sounds from Wally Heider’s studio were pristine, showcasing Crosby’s exquisitely tuned guitar, haunting multi-tracked voicings and lush harmonies treated with a subtle, shimmering ambience.

The album begins with a communal anthem, “Music Is Love.” Co-written by Crosby, Nash and Young, this circular chant has the threesome singing over churning acoustic guitars. The next tune, “Cowboy Movie,” is the polar opposite, as the saga is overtly analogous to the 1970 breakup of CSNY. Starring four willful protagonists and illuminating their mistrust, paranoia and romantic rivalry for the exotic Raven (who leads them to their demise), the western drama also features sharp dueling guitars from Neil Young and Jerry Garcia and couldn’t feel more urgent.

Despite his abrasiveness, Crosby was at his best playing among others. Introspective and antisocial, he was wounded but still vital enough to transform his pain into high art on If Only I Could Remember My Name.

I admit that I stepped into the kitchen to make a sandwich during the program and missed whatever the 25th-anniversary music memory was that Quick Picks had cooked up. But I did get back in time for the final portion of the show where they focused on the 10th anniversary of Michael Fracasso’s home-crafted video for his song “Saint Monday.”

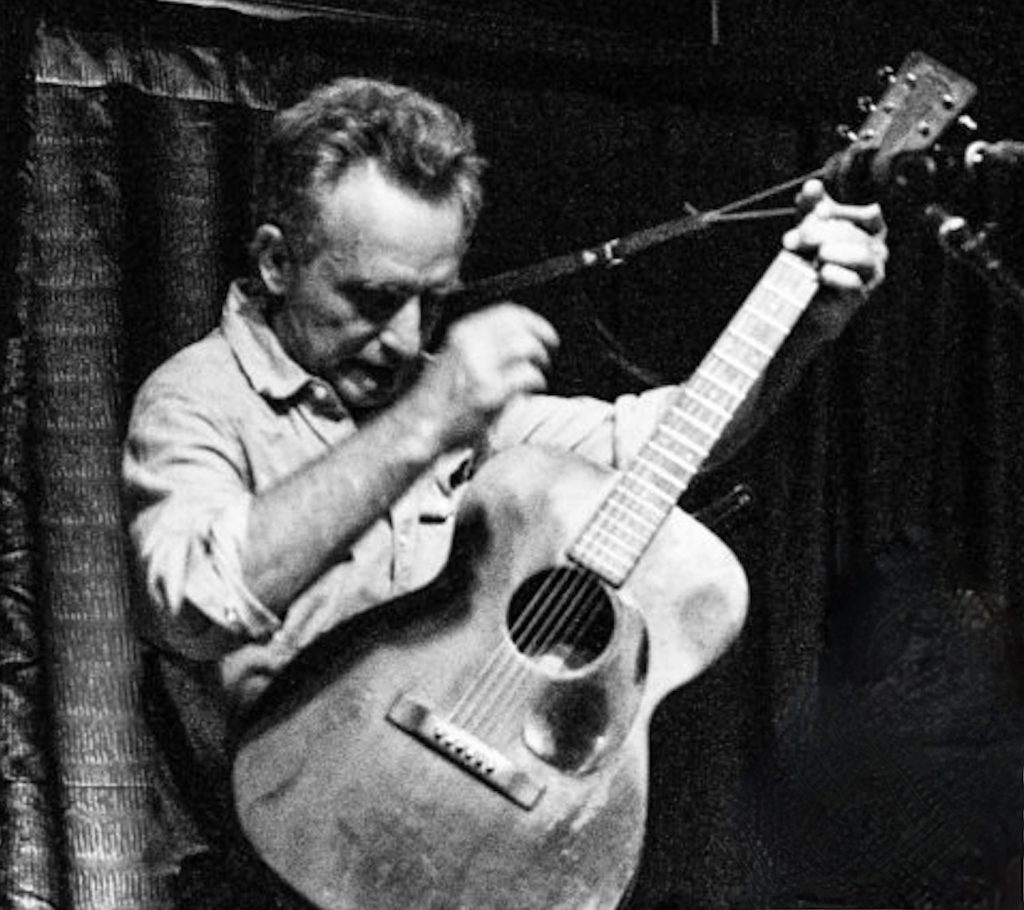

Ten years ago, novelist Jim Lewis, who lives in Austin, Texas, was so enamored with the artistry of Fracasso that he agreed to co-produce his 2011 collection, Saint Monday. Fracasso’s talents as a singer and songwriter were no secret—he’d already released a half-dozen acclaimed albums and worked closely with fellow Austinites like Charlie Sexton and Patty Griffin. Lewis had never produced a record before, but despite his inexperience and alternative rock sensibilities the results of their collaboration were impressive. Not only that, Lewis wrote an article that ended up in the New York Times about his experience making the record with Fracasso titled “For Novelist, A Magical Turn As A Record Producer.”

The album has several standout tracks: full-flowered songwriting gems like “Gypsy Moth,” stomping murder ballad “Elizabeth Lee” and a gripping version of John Lennon’s “Working Class Hero.” Then, of course, there’s “Saint Monday.” The term itself refers to the tradition of absenteeism that occurs at the beginning of the work week. When describing his song, Fracasso said that “Saint Monday” is “about those who live in the underbelly of America. In the 18th century, [it was] a euphemism for factory workers who got too drunk over the weekend to show up for work. It takes place in the rust belt where the hookers and musicians have replaced the steel workers and still try to make a living.”

But I must confess the real reason why I’m telling you all about the Anniversary Channel is that they actually quoted me in this Quick Picks segment. Ten years ago, I sent out an email extolling the virtues of the “Saint Monday” video on YouTube. That happened when Fracasso first sketched out the plot for his vignette using simple drawings to illustrate the action. My response to this rough-cut presentation of music and American primitivism was simply: Your job is already done. Or, as I said a decade ago in my announcement that the ANC was so kind to recall, “Fracasso put together this storyboard for a proposed music video. We said, ‘This is the video!’”

So, what do you think? Was I right, or was I right? Maybe next time we can discuss the Anniversary Channel’s other fun weekend program, Andy Warhol’s Fifteen Minutes.