MAGNET’s Mitch Myers explores the unique bond between two guitarists and the mystique of an influential acoustic debut from 1969

Leo Kottke’s debut album, 6- And 12-String Guitar, first came to light in 1969. It was a straightforward antidote to the fervor of the hard-rock scene at the time, and his work was lauded as a welcome alternative to the era’s heavier artists. Kottke’s technical virtuosity emerged fully formed on the LP, but it was more than the quick-fingered precision that filled the grooves with excitement. The record had captured something both astonishing and ephemeral—acoustic-guitar lightning in a jar—and opened the lid for all to hear.

The story of 6- And 12-String Guitar isn’t just Kottke’s. It’s the tale of two guitarists: Leo Kottke and John Fahey. The men were still worlds apart when young Kottke recorded his landmark album; he was playing the coffeehouse scene in Minneapolis while the enigmatic Fahey was running Takoma Records way out west in California. Kottke had simply sent Takoma a demo tape that impressed Fahey, and the elder musician commissioned a recording session that would ultimately become 6- And 12-String Guitar. Fahey had already been making his own solo steel-string guitar albums for his insurgent record label since 1959, and his influence on Kottke was profound.

“I have a real fondness for [6- And 12-String Guitar] because of John Fahey,” says Kottke. “John was the only guy interested in recording me at that time, and if it hadn’t been for him, none of these things would have happened. My whole life was at a critical point, and it pivoted because of John. I wasn’t planning to do anything as far as making a living as a guitar player. I just wanted to meet John.”

Kottke was left to his own devices for the album’s creation, and his process was remarkably basic. But a little 1960s synchronicity graced the recording session as well. “It was recorded at Empire Photo Sound, a little idea of a studio working out of a warehouse,” says Kottke. “I just looked them up in the phone book … The only other thing they had done at the time were the first promos for the 747 airplane—they weren’t set up for me at all.”

The elements of the Minneapolis studio were crude, but the bright, clear sound attained on 6- And 12-String Guitar would be difficult to improve on, even today. “The engineer was Scott Rivard (who went on to work for A Prairie Home Companion),” says Kottke. “They hung sheets in the warehouse, and it was as if I was in this little square white room. They used an old technique for the microphone placements called near/far. The 87 microphone was near the guitar and the 451 microphone was further away.”

Although the young musician had his performance repertoire down cold, he still felt the high anxiety of his first recording session. “I remember being scared to death,” says Kottke. “I was just petrified, so concerned to get it right—and I didn’t know what right was. My foot made a lot of noise, so I took my shoes off.”

Despite the nervousness, Kottke completed the task in just more than three hours. And he actually credits his guitar for the easy time he had in the studio.

“The thing about [6- And 12-String Guitar] is the 12-string,” says Kottke. “It was unusual: a Gibson B-45. I had stripped the finish off it. I’d heard that raw linseed oil was a good way to finish a guitar, and it sounded fantastic. I also painted that guitar brown. It had a magical quality … I’ve always thought that a big part of the record’s staying power is the sound of the guitar.”

Kottke’s enchanted B-45 served him well, but the notably low guitar tunings he used on the album were mostly guesswork. “Originally, 12-string guitars were supposed to be tuned down to accommodate the tension, but most weren’t strung that way,” says Kottke. “This one was strung with silken steel strings, and I tuned it way down. I had no idea of actual pitch, and it was in between everything.”

Ironically, Kottke’s symbiosis with his 12-string also led to some difficult moments. “I went out to meet John (in Portland), and right after the first job we did together, my guitar was stolen,” he says. “It sent me into a tailspin, and I had to re-learn everything. The guitar meant so much to me, and when I used other guitars, it sounded like crap and drove me crazy for years. The six-strings were never a problem. It was the first 12-string that sounded like that, and it was one of a kind. I found a bunch of B-45s, and they just don’t sound the same.”

Kottke recovered from the loss of his favored instrument, and his admiration for Fahey remained undiminished. “With John, you have to figure he stole the guitar,” he says jokingly. “I was so happy to meet him. The whole trip out west—it was just to meet John Fahey. My friend had John’s Blind Joe Death album and it was clear there was this whole musical world that had been around, but John was the only one who knew it. ‘Sligo River Blues’—I learned it off of Blind Joe Death. That record was the one for me, and to meet the guy who had done that stuff was really a big deal. He could have my guitar.”

For 6- And 12-String Guitar’s release, Fahey made simple-yet-prudent editorial decisions regarding the performances. “None of us knew anything about sequencing,” says Kottke. “We sent it to John just as we did it. It was the actual sequence, but John just took off three tracks and released it as a record. It was the simplest record I ever made. I have another soft spot for it because it was the only recording I made where it was all the material I knew. It would never be the same after that.”

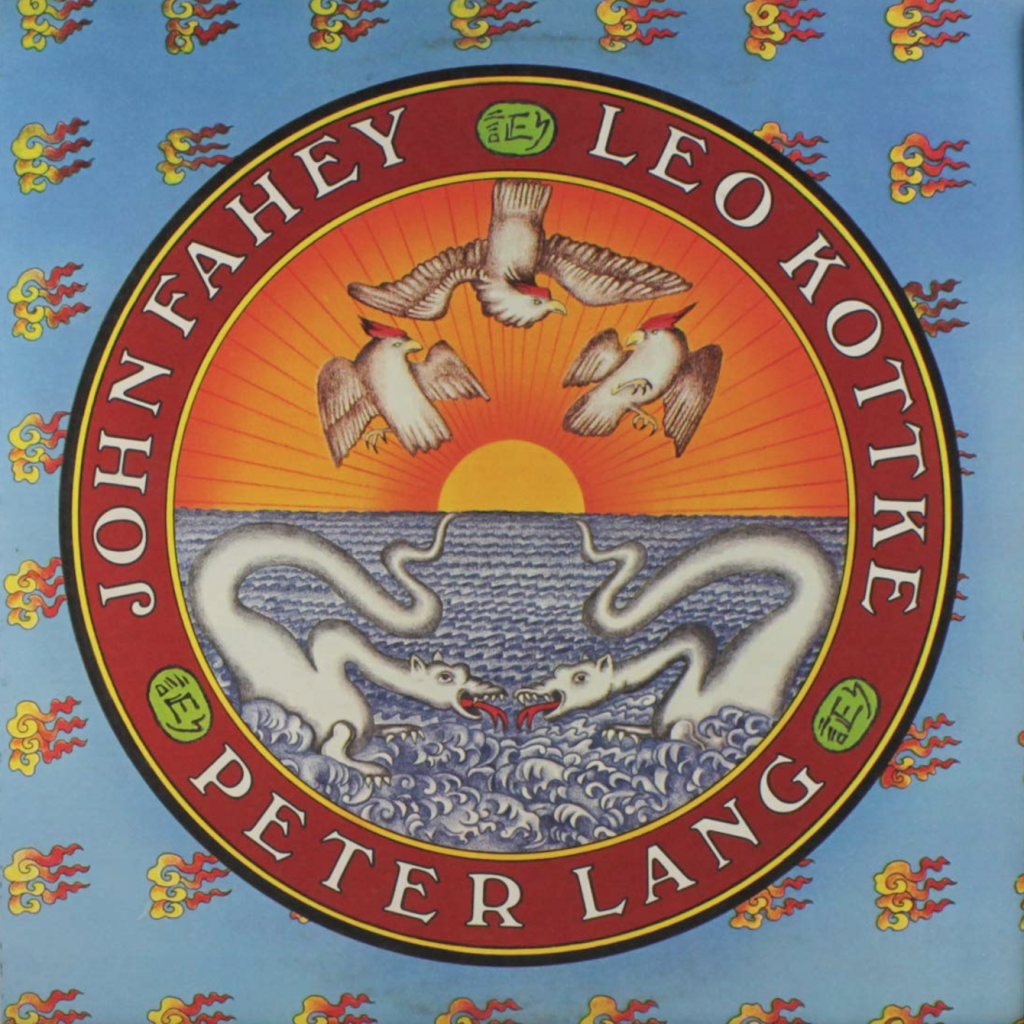

Subsequent reissues of the album have contained the same 14 songs without variation or additions. For those wondering what became of the three extra tracks Fahey deleted from the original studio recordings, you can find them on Takoma’s classic 1974 guitar compilation John Fahey/Peter Lang/Leo Kottke.

Looking back, Kottke has come to terms with Fahey’s essential role as an imposing mentor who literally launched his career. “At John’s funeral, I realized it was always obvious that I wouldn’t be working if it weren’t for John,” says Kottke. “I’d be playing, but not working as a musician. It struck me that John gave me my whole life. He was one of those dangerous teachers where your entire life is in jeopardy, and it’s all in that record. John was the real thing.”

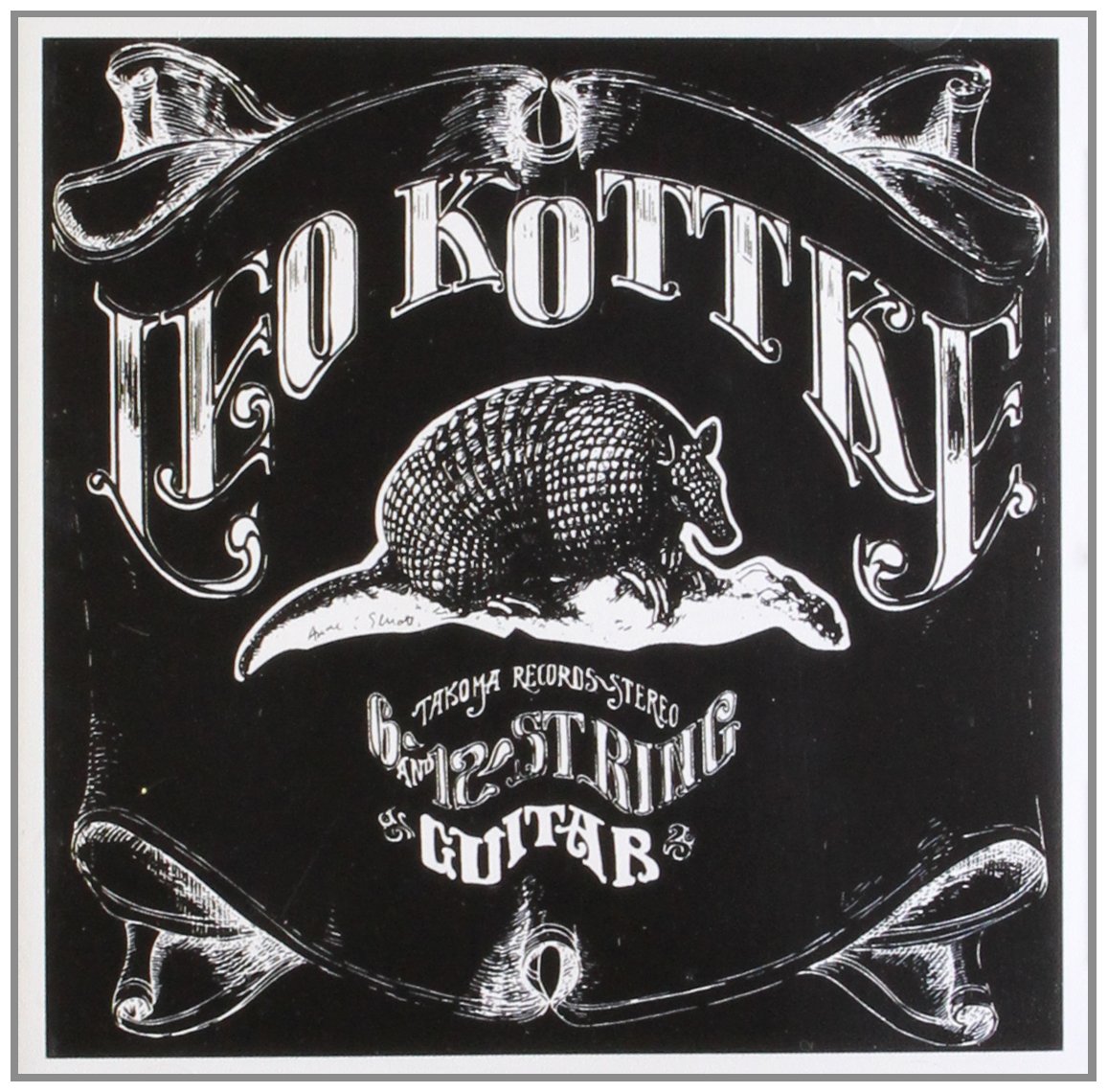

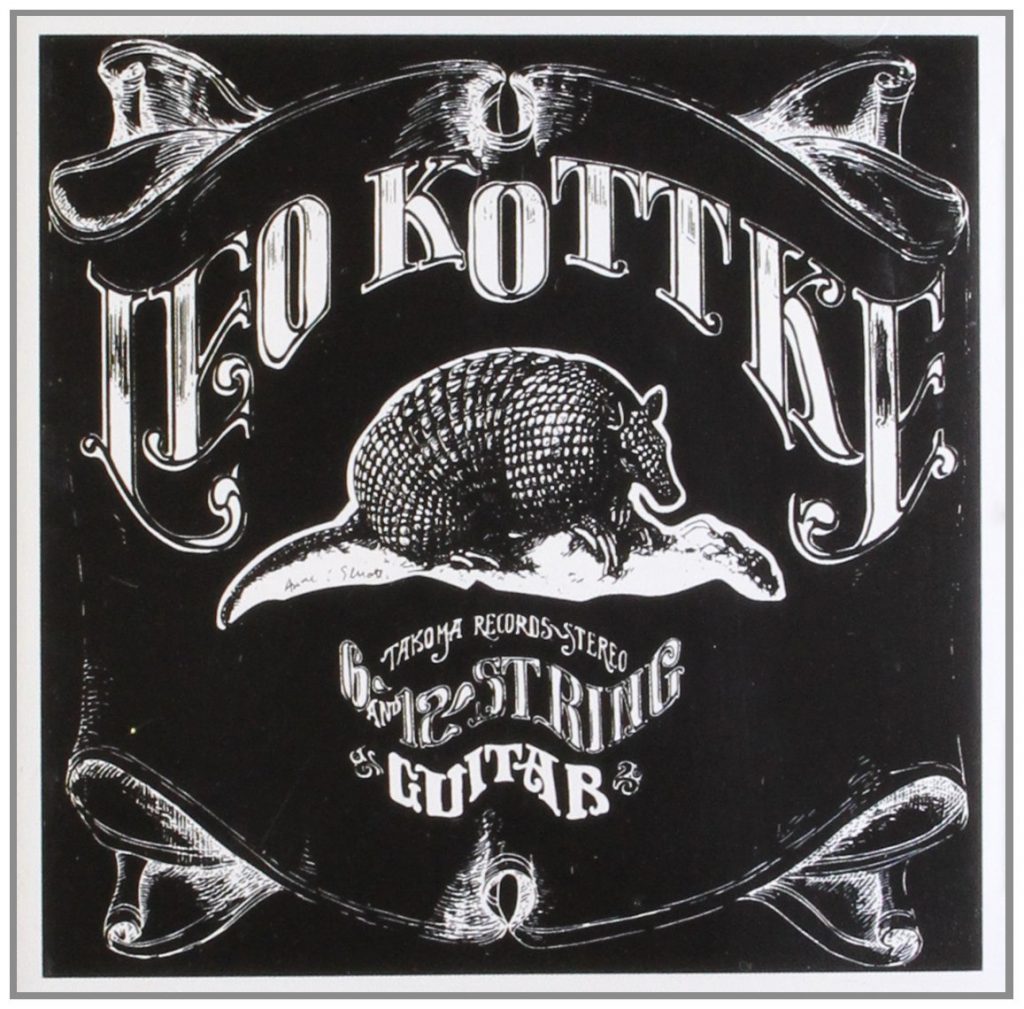

Along with his spellbinding instrumental exhibition, 6- And 12-String Guitar was noticed for its distinctive cover art: a black-and-white drawing of an armadillo. Affectionately known as the Armadillo Album, the LP—and its arcane illustration—somehow captured the hearts and minds of acoustic-music fans across the country. Where did the armadillo come from?

“I was performing at a coffeehouse called The Scholar,” says Kottke. “A woman (Annie Elliott) who worked there made the menus and drew the armadillo. One night I was having trouble with my 12-string and said, ‘There’s an armadillo in my guitar.’ She put it on the menu, and I loved it and asked her to do the album cover … I was always really happy about the armadillo. Then I got booked at the Armadillo World Headquarters in Austin, Texas, and before I played there, they took me to somebody’s house and interrogated me. They wanted to know all about my relationship with the armadillo. We became a real pair, the Armadillo World HQ and me. I really wanted to be a performer, and the HQ showed me what a real performance could be.”

The Armadillo Album eventually sold more than half-a-million copies. Although it took decades, the record’s slow-yet-undeniable impact helped elevate the concept of solo steel-string guitar into an acknowledged American art form. The disc gained national attention in 1970 thanks to a glowing review in Rolling Stone, and while his front-porch fingerpicking may have been out of step with the amplified sounds of the times, Kottke struck a chord that continues to resonate.

More than anyone, Kottke was surprised by the enthusiastic reaction to his first album. “I was flabbergasted at the reception of that record, and I didn’t realize until years later how much impact it had,” he says. “The Rolling Stone article was important. And there were also two guys in Chicago: Randy Morrison on WLS and John Schaffer at WXRT. They were both playing it. Radio still existed then, and DJs could pick up a record with no label behind it—it was a different world—and the record just took off.”

Certainly, the late 1960s were an exotic time for music and pop culture, and in retrospect, Kottke’s dazzling display doesn’t seem so out of place. Tapping into the collective unconscious of the era, Kottke and Fahey found each other from across the country to create a unique acoustic-guitar document that has withstood the test of time.

“When someone is really, really enjoying themselves, it can happen,” says Kottke. “I think that’s another reason why people like that record and began playing guitar that way. It’s a great privilege of the job to be part of that. I was recording it for this oddball character, and it made me feel like I had found home. John liked it for the same reason I liked it: for what it was.”