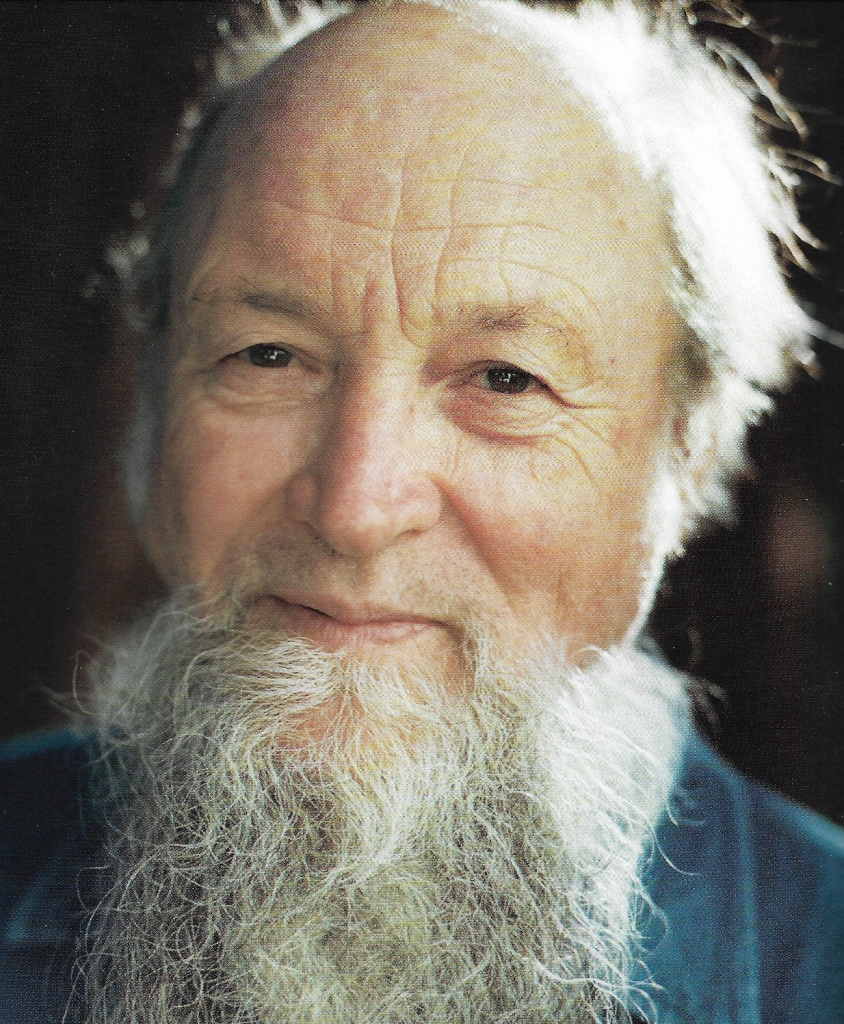

What do Brian Eno, Philip Glass and Pete Townshend have in common? MAGNET’s Mitch Myers revisits a harmonious encounter with Terry Riley, the Godfather Of Modern Minimalism. Photos by Lenny Gonzalez

It’s early in 2001, and I’m among the pastoral foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in rural Camptonville, Calif., spending an afternoon at Terry Riley’s secluded Sri Moonshine Ranch. What does the Godfather Of Modern Minimalism have in store for us today? A batch of salsa, of course.

Riley and his wife Ann (who passed away in 2015) have been making salsa every summer for 25 years and have their industrious cooking process down to a science. Using hot chilies grown on their farm as well as peppers from neighbors and friends in New Mexico, they chop, stir and boll impressive amounts of organic tomatoes, onions, cilantro and other ingredients I’m not at liberty to divulge. The net result is 18 vacuum-packed jars of Riley salsa, aptly dubbed “Hot 2000.” After lunch, we retire to Riley’s upstairs workspace, where two grand pianos sit side by side. It’s here, far from urban and social distractions, where Riley composes music.

One of Riley’s recent projects has him paired with the Kronos Quartet working for NASA. Thanks in no small part to Kronos leader David Harrington, Riley is commissioned to compose music based on radio waves collected by the Voyager space shuttle.

“NASA has done a couple of music projects before,” says Riley. “This one is based on Voyager’s exploration, which flew by all of the planets. On board Voyager was a device called the Plasma Wave Receptor, which was invented by a Dr. Gurnett in Iowa. This device is able to receive radio waves the planets themselves broadcast, and each planet has a different sound wave.”

Riley is the perfect candidate for NASA’s space-age string quartets. Here on Earth, he’s spent his time creating music light years ahead of his peers. Riley made his giant leap in the ’60s with In C, a towering obelisk of a composition that cast an influential shadow over Philip Glass, Brian Eno and Pete Townshend (remember the intro to “Baba O’Riley” from Who’s Next?) and blurred the boundaries between classical music, avant-garde experimentalism and trance-inducing improvisation for all who followed.

Born in Colfax, Calif., in 1935, Riley was barrelhouse piano prodigy by the time he arrived at San Francisco State College in the mid-’50s. One of Riley’s early peers was Pauline Oliveros, a groundbreaking performer/composer who remains active in progressive music circles. (Oliveros died in 2016.) “When we were going to school together, Terry was a really hot pianist,” recalls Oliveros. “It was quite clear that he was an enormous talent and had music coming out of his pores.”

In 1959, Riley left San Francisco State, enrolling at the University of California at Berkeley and eventually becoming a member of the San Francisco Tape Music Center, an illustrious workshop on Divisadero Street that became a prime gathering place for Northern California’s avant-garde community. Along with filmmakers, dancers and artists, Riley forged relationships with a list of musicians that now reads like a post-classical/avant-electronic/Eastern-drone who’s-who.

Besides collaborating with Oliveros, Riley exchanged ideas with young composers like Morton Subotnick, Steve Reich and Ramon Sender; even future Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh was hanging around. Most importantly, Riley encountered La Monte Young at Berkeley. If Riley is the founding father of modern minimalism, Young is the genre’s designated granddad. When the two met in 1960, Young had already developed his ideas on extended tones and how musical time can pass with a minimum of sound. During the ’60s, Riley, Tony Conrad and the Velvet Underground’s John Cale were part of Young’s Theater Of Eternal Music, and the group’s droning, drug-fueled performances would often last through the night.

“Terry Riley is the most harmonious musician to work with I have ever known,” says Young. “I appreciate it more and more over the years, although we don’t have as frequent an opportunity to perform and rehearse together. We really were able to capitalize on this in the Theater Of Eternal Music because there was so much co-creativity encouraged in the group.”

The ’60s were a period of heady discovery for Riley. Outgrowing the honky-tonk piano, he began experimenting with tape manipulations and employed a tape-delay device called the time-lag accumulator. Some compositions reflected the use of psychedelic drugs, like mesmerizing tape-loop construction “Mescalin Mix,” which was recorded between 1960 and 1962 and inspired by John Cage and musician/engineer Richard Maxfield.

“I went to Europe for a couple of years after I got out of Berkeley,” says Riley. “That’s when I had a big period of bringing my ideas into focus and got to work with Chet Baker in Paris. The Tape Music Center had gotten started, and when I came back, I reconnected with Pauline and Morton Subotnick. There was a lot of work I’d been doing, including (music for 1963 theater production) The Gift with Chet Baker. I found, through accident, that tape loops build up this long form. I’d sit there listening as this loop was repeating over and over, creating a whole musical form. The way time passes and the way the mind works when it focuses on an object, it’s like a meditation. A tape loop is a kind of mantra.”

Both “Mescalin Mix” and his work on The Gift involved sonic fragmentation and the stretching and slackening of time via now-primitive tape technology. Whether looping tape through two recorders or extending lengths of ribbon out of his window, around a wine bottle and then back into a tape machine, Riley was at the forefront of experimental music.

All this work, however, paled at the debut of Riley’s most memorable composition, In C. A seminal work with its nonstop pulse, repetitive themes and interlocking modal melodies, In C was devised by Riley during a bus trip and written out in the space of two days.

“In 1964, I’d been working on all these electronic pieces,” says Riley. “I’d also written In C, but it had never been performed. So I took all this stuff down to the Tape Music Center. I met Steve Reich and John Gibson, and they put together this pick-up band. And In C was recorded.”

In C took Riley’s hypnotic tape-loop concepts and brought the repetitive motif back to traditional acoustic instrumentation. The cosmic sound cycle gradually blossoms into a shimmering aural experience with 53 recurring figures.

Crediting Young with the spirit of In C but not the content, Riley is proud of the resilient piece, which has been performed all over the world. There are Canadian and Italian versions, a 25th anniversary concert recording and even a rendition by the Shanghai Film orchestra using traditional Chinese instruments. In the ’70s, a 15-piece rock band performed In C; in the ’80s, there was an all-guitar performance; and in the late ’90s, Lincoln Center Festival featured an electronic version with Robert Moog playing synthesizer. CBS Records released Riley’s most distinguished rendering of In C in 1968, and while there have been countless interpretations, the clarity and precision of this vintage performance remains unmatched.

When I comment to Kronos’ Harrington that one couldn’t write about Riley without discussing In C, his response is succinct. “It’s the same way you can’t talk about Stravinsky without discussing The Rite Of Spring,” he says. “In C is an idea about life, about making music together and about community. It’s so simple and yet so profound, it always sounds right and it always sounds different.”

“In C is a perfect masterpiece,” says Young. “I compare it with the theme from the ‘funeral march’ in Mahler’s Fifth Symphony and Schoenberg’s opening theme in Verklärte Nacht. Terry influenced not only Steve Reich, Philip Glass and their protégés, such as John Adams, but his influence spread out to certain European rock groups, such as Daevid Allen’s Gong, Can and Tangerine Dream. In the case of these rock groups, I think sometimes Terry was the direct link.”

Invigorated by In C and eager to return to Europe, the Rileys made their way across America in a Volkswagen bus. “I’d been in Mexico living the hippie lifestyle and ended up in New York broke, so we traded our van for money for a loft,” says Riley. Settling in Manhattan, Ann Riley went to work as a schoolteacher while Riley resumed playing music with Young.

“La Monte was my main contact,” says Riley. “Tony (Conrad) and John (Cale) and Marian (Zazeela, Young’s wife) and La Monte were singing on a very regular basis. John had already started work with the Velvet Underground. Within a couple of months, he left, and I found myself as one of the main members of the group. La Monte, Marian and I were singing, and Tony was playing an amplified violin. In addition, we used little tank motors for drones and, later on, sine-wave generators.”

While his tenure with Young was brief, Riley established himself in Manhattan’s music/art/loft scene. “I left the group because I wanted to get back to the work I’d been doing after In C,” he says. “I got this little harmonium that had a vacuum-cleaner motor. It was primitive, but I started playing keyboard studies on it and doing some of the first loft concerts around New York.”

Ambitious tunes like “Poppy Nogood And The Phantom Band” evolved into mesmerizing solo concerts that incorporated Riley’s keyboard studies and tape delays as well as a soprano-saxophone style that borrowed from Young and John Coltrane.

Riley’s hyperbolic performances in 1967 and 1968 would often last all night and into the morning, predating the tranced-out rave culture by two decades. British DJ Mixmaster Morris keeps an extensive library of Riley recordings and has long held him as one of the great innovators in contemporary music. “(Riley’s) use of electronic modulation in a live context was 30 years ahead of the field,” says Morris.

Conrad (who passed away in 2016) was particularly impressed with Riley’s artistic metamorphosis during this time. “Terry’s keyboard work had evolved a conceptual coherence and technical mastery that was on a tier above any musician then playing and was as original and articulate as Charlie Parker in the early ’40s or David Tudor and John Cage in the ’50s,” says Conrad. “The magic and power of the soundscape that Terry created in concerts defied all explanation or understanding. His proficiency as a performer, combined with the intricacy of his rhythmic and melodic structure, left most listeners dumbfounded, simply able to drink in the endlessly undulating liquidity of his sound.”

Scoring a three-album deal with CBS for the label’s Masterworks series, Riley recorded his classic version of In C with an accomplished group of musicians including Stuart Dempster on trombone, Jon Hassell on trumpet and pianist Margaret Hassell playing the C-note “pulse.” It quickly galvanized Riley’s reputation as a serious composer, but it was marketed toward the younger record-buying public. CBS pitched In C and Riley’s enthralling follow-up album, 1969’s A Rainbow In Curved Air, as psychedelic-rock brain candy, advertising them alongside other Masterworks synth oddities like Walter Carlos’ Switched On Bach and Subotnick’s Touch.

Besides furthering the technical aspects of electronic music, Riley was also effecting a ground-zero change in the realm of ambient philosophy. West Coast intellectual/inventor/entrepreneur Stuart Brand says, “Riley had profound and immediate influence on Brian Eno, evident in his albums Our Life In The Bush Of Ghosts and Music For Airports. In C persuaded Brian that endlessly original algorithmic music doing permutations on a sound palette designed by the composer could make for brilliant listening. This is something Brian and I have talked about a lot.”

While In C was the acoustic precursor to many future minimalist works, A Rainbow In Curved Air was a one-man electric circus geared to recreate the experience of Riley’s all-night concerts. “There was a sensibility that was changing in the late ’60s,” says Riley. “It would have been hard to create these records five years earlier. The Curved Air sessions were the first recording sessions made on an eight-track machine at CBS. They wheeled it in, it was brand new and nobody had even used it yet.”

While Riley was recording A Rainbow In Curved Air, he also worked with Cale on enigmatic 1971 collaboration Church Of Anthrax. Extending the disciplines they had practiced with Young and employing rock drummers who insisted on playing in 4/4 time, Cale and Riley created a cryptic rock/jazz/synth/drone hybrid. “I was recording Church Of Anthrax with John in the afternoon, and then I’d go in late at night to record A Rainbow In Curved Air,” says Riley. “Essentially, John and I just improvised. One thing we share in common is not too much preparation beforehand.”

With critical success, invitations to record with rock artists and the immediate influence of In C, Riley was poised to cement his position in New York’s competitive music community. But it was not to be.

Once again, Young influenced Riley when he introduced him to raga singer Pandit Pran Nath. “La Monte had arranged to help bring him over to the States to teach,” says Riley. “I was powerfully moved, not just by his music but by him as a person. I was also at a point in my career where I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. So during the next 26 years, even though I was composing and giving keyboard concerts, I was trying to learn Indian classical music in the traditional way.”

In 1970, Riley went to India to study with Pran Nath. After six months of intense musical training, the singer told Riley he should return to work in America. “It’s a very personal relationship when you study under your masters,” says Riley. “You don’t come for a lesson once a week—you work very closely because it’s a responsibility on both persons’ part. You have to devote your life to it.” Riley’s mentor eventually moved to the Bay Area, and their friendship lasted until Pran Nath’s death in 1996.

Returning to California in 1971 and taking an instructor’s position at Mills College in Oakland, Riley practiced the teachings of Pran Nath and improvised music without notating his work in written fashion. He continued to record several meta-trance classics, including Happy Endings, Persian Surgery Dervishes (both from 1972) and West-meets-East electro-tone-poem Shri Camel (from 1980), which uses a Yamaha organ calibrated to a unique tuning system called “just intonation.” Riley’s solo electronic work was visionary, but there were artistic partnerships to come as well.

In 1979, Riley encountered the Kronos Quartet at Mills College. Since, Riley has composed more than a dozen string pieces for Kronos. The Quartet’s recording of Cadenza On The Night Plain was selected as one of the 10 best classical albums of 1985 by both Time and Newsweek, and 1989’s Salome Dances For Peace was nominated for a Grammy. On 25 Years, the Quartet’s 1998 10-CD retrospective boxed set, Kronos devotes an entire disc to Riley’s work alongside contemporaries like Glass, Reich and Adams, as well as obscure luminaries like Henryk Gorecki and Morton Feldman.

“David (Harrington) talked me into writing for the Kronos,” says Riley. “They’re my most consistent collaborators in music. It brought me out of an isolated solo performance career. I also started writing for other groups and ended up getting orchestral commissions.”

Besides writing acclaimed compositions for string quartets, saxpohone quartets and orchestras, Riley has maintained a passion for improvising contemplative solo pieces on the piano. His highly evolved use of just intonation is exemplified on stellar 1985 double-disc The Harp Of New Albion, and conventionally tuned piano explorations like 1996’s Lisbon Concert are positively transcendent. No matter what aspect of music Riley approaches, it reflects the sum total of his experience and integrates a world of sound. Guitarist Henry Kaiser played on the 25th anniversary edition of In C and maintains that Riley is “the most significant and influential composer since World War II”

Over the last few years, Riley has applied himself to writing guitar music, which resulted in 1995’s Spanish-tinged The Book Of Abbeyozzud, featuring David Tanenbaum and Riley’s son Gyan on guitar. Joan Jean Renaud, former cellist of the Kronos Quartet, is playing a new piece she commissioned Riley to compose. Riley has also performed a series of improvisational duets with Italian bassist Stefano Scodanibbio and is currently touring with Paul Dresher’s electro-acoustic ensemble.

Yet Riley’s career path has been much more difficult to follow in comparison with those of his contemporaries. While Glass and Reich record for the prestigious Nonesuch label and vie for commissions, grants and concert performances in pro and businesslike fashion, Riley resides at his ranch like a venerable music Buddha, performing sporadically and recording for small record labels like New Albion and Celestial Harmonies. Although some archival recordings from the early ’60s have been made available, much of Riley’s outstanding body of work is still waiting to be rediscovered.

Sitting in his secluded home, Riley radiates a distinct sense of inner peace as he looks back at his uncommon career. “The choices I’ve made have been for the music and my own soul,” he concludes. “When I walked away from New York, I knew fame wouldn’t have given me any happiness if it weren’t based on a musical choice. Pran Nath said, ‘Just enough fame to keep doing your work is enough,’ and I thought that was good advice. I feel terrifically lucky every day I get up and give thanks for what’s happened. What really makes me sad is to see young musicians who are hopeless about their situations. My advice is put it all into the music. That’s the only thing you can do, because you don’t know what kind of hand fate is going to deal you. At least your own soul is going to be getting some feedback.”