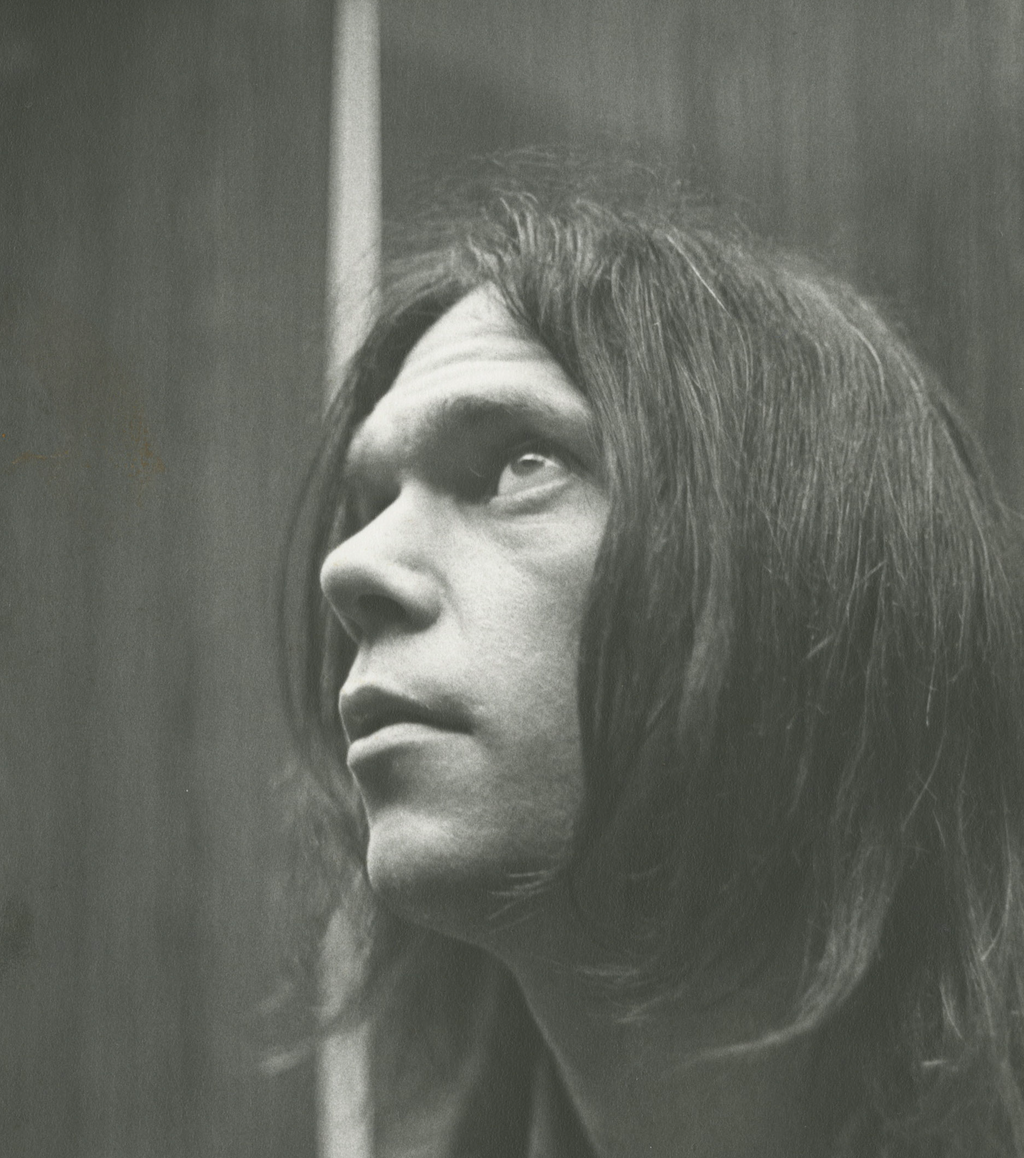

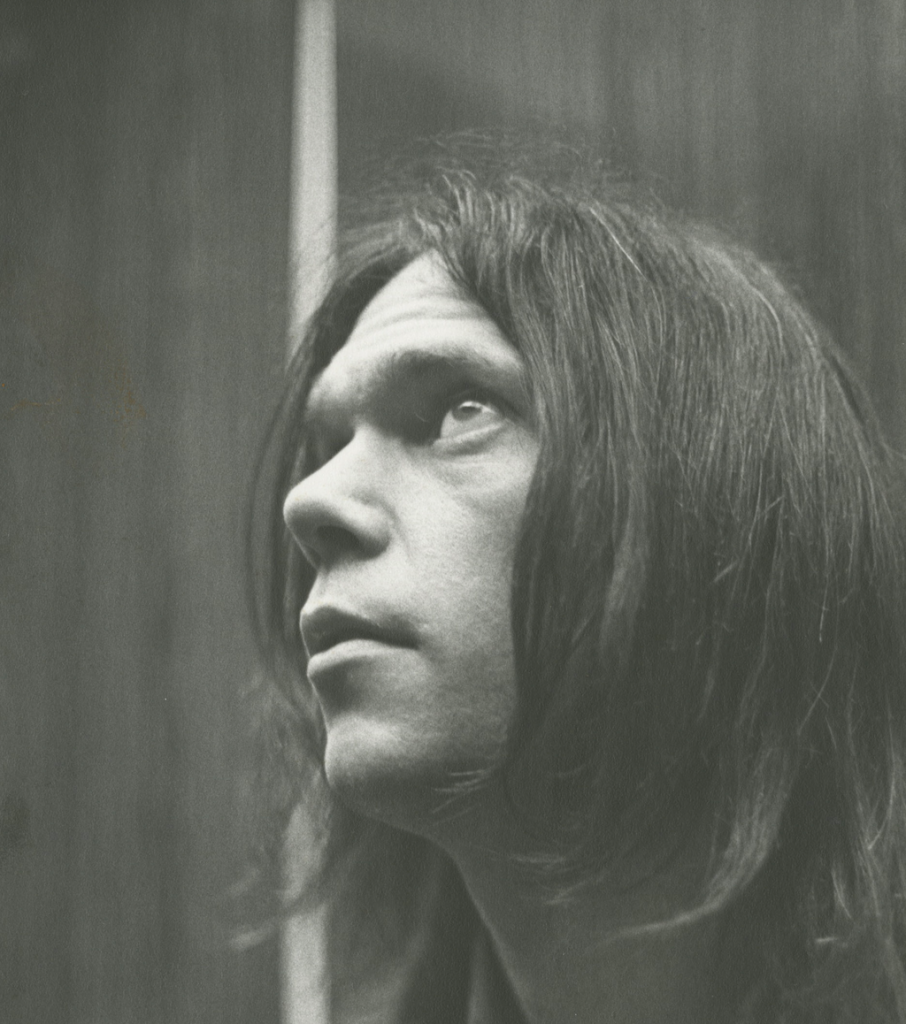

Everyone knows Neil Young is everywhere—except Spotify, that is. MAGNET’s Mitch Myers says tonight’s the night to start a new Neil playlist with songs also featuring the (un)usual suspects.

When the Neil Young kerfuffle first made news, it was clear that we’d have to issue a statement, eventually. So, for the record, rest assured that the Basement Vapes remains completely judgment free as to your music-delivery preferences. That said, if you’re still inclined to listen to Neil Young, we do have suggestions. There’s just too much Neil material out there, and the preponderance of his work can be daunting—so many classics, alternate versions, previously unreleased stuff, new albums, older music, live archives. A most contemporary gamut.

Let’s just start a simple playlist with the five Neil tracks found on the Stills/Young Band album, Long May You Run. Odds are you haven’t worn out those tunes and may have forgotten some of them altogether. That’s because most folks have rarely bothered to plough through all of the Stephen Stills tracks just for a little more Neil. In any case, this record boasts a decent batch of Young music from 1976 that almost became a Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young album, until it didn’t. Disclaimer: There’s nothing wrong with the four Stephen Stills tunes on this collection, but someone else will have to write about that.

When he and Stills made Long May You Run, Young had been recording, touring and drugging hard for a while. He was a successful, strong-willed alpha male among strong young alphas and prone to follow his instincts above all else. Chronologically, this relatively laidback album lands smack between two hard-edged, guitar-driven solo records: 1975’s Zuma and 1976’s American Stars And Bars. Heavy musical bookends, by any standard.

One of the thoughts behind their collaboration was to tap into the kinetic energy generated between Young and Stills’ guitar interplay, which had first caught fire in the 1960s when they were bandmates in Buffalo Springfield. A worthwhile intent, but things just didn’t turn out that way. The recording sessions were quickly organized using musicians from a group that Stills had already put together for himself. Rather than the pair sounding joyously united, their effort felt more like alternating solo tracks, with Young’s tunes defaulting amiably into a mellow, country-rock vibe.

“Long May You Run” is a nice gentle anthem, but not much of a hit at the time. While Young composed it as an ode to his first car (a 1948 Buick Roadmaster hearse that he called Mort), the song could almost be about anyone, or any number of things. Like a friend, or maybe even a band. Beyond that commercial title track, there’s some sense Neil was holding back his better songs for his next solo album. Still, the rollicking “Let It Shine” holds up quite well, as does Young’s stark, ominous “Fountainbleau,” with its howling-guitar showcase.

Not surprisingly, the year surrounding Long May You Run was fraught with disruptions and disloyalties. After first reconnecting with Stills and unexpectedly performing with him in concert, Young engaged in a rapid succession of betrayals. In short order, he dropped his own band (Crazy Horse) to work with Stills, removed the guest vocals by David Crosby and Graham Nash from the Stills/Young recordings and, ultimately, abandoned Stills and his group in the middle of their tour promoting the new album.

Rather that confronting his peers face to face, the conveyance of these betrayals mostly came down through Young’s management. At least he wrote Stills a personal note. This was the concert tour where Neil bailed on everyone without warning and ended up sharing the bad news with Stills in a telegram that said, “Dear Stephen, funny how some things that start spontaneously end that way. Eat a peach. Neil.”

Timing was everything for Young, complicated by a surplus of opportunities, artistic regret and a profound sense of guilt. Too much business, money, talent, ego and drugs (in particular, a great deal of cocaine). Dubious of commercial music formulas designed for the sake of success, he kept his own counsel and made a series of unpopular decisions, pushing back on the very projects that he had committed to. Basically, Young—a man of whims, contradictions and sometimes unprincipled idealism—needed to stay in control and wasn’t born to follow.

Right or wrong, most musicians ultimately accept Young’s need to lead, make/change their own plans accordingly and try to forgive or forget the breakdowns of trust that occur as just another broken arrow. In 1976, Stills was drifting aimlessly in his career and was no longer getting along with Atlantic Records. Crosby and Nash had found their niche and were already making their third album as a soft-rock duo. Young invited them to add their voices to some Stills/Young album tracks, which obviously pointed to a full-on CSNY reunion. But soon after Crosby and Nash went back to completing their own album Young had a change of heart and erased their contributions from Long May You Run.

Never reluctant to make a statement, Young’s tough reversals—removing valued vocals from these recordings, dropping out of his new band‘s promo tour—were stubborn objections to the commercialized pressure of these “collaborative” projects. It also frames many of the CSNY-related efforts as somewhat formulaic and arbitrary.

While Young rarely shared his best tunes on group recordings, his tracks on latter-era Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young albums are examples of the industry compromises he was willing to make. So, to round out this playlist, we can include his melodic, middle-of-the-road tunes on 1988’s American Dream and 1999’s Looking Forward. Both CSNY reunion albums follow the Stills/Young template of radio-friendly title tracks penned by Neil, and it’s always good to hear all four of their voices singing together for old time’s sake.

Finally, just to be nostalgic, consistent and discerning, let’s incorporate Young’s vintage performances from CSNY’s 1971 live album, 4-Way Street, especially his nine-minute solo tour-de-force medley of “The Loner/Cinnamon Girl/Down By The River.” Anyway, it’s about time that you made your own Neil Young playlist. It’s a fun way to approach things, and we should all feel free to do that, unless you still have to find the cost of freedom. If so, don’t ask me.