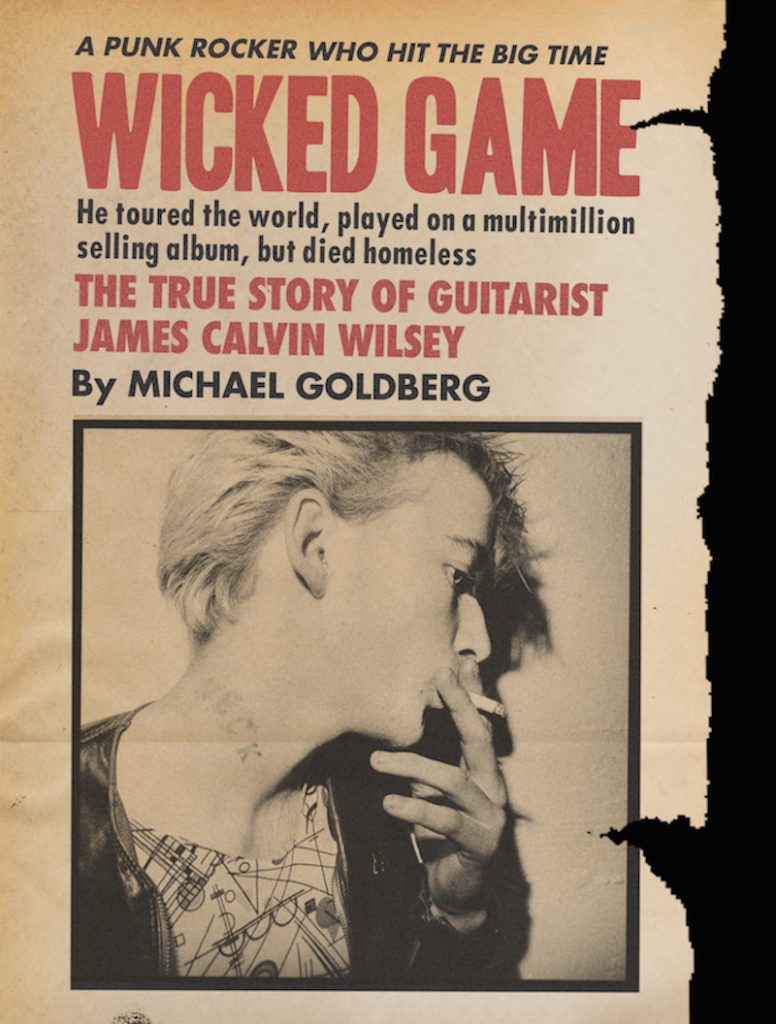

For veteran music journalist Michael Goldberg, the stakes couldn’t be more personal when it comes to guitarist Jimmy Wilsey. The two were friends—at least in the beginning, when Chris Isaak and his band, Silvertone, were setting the standard for San Francisco Bay Area post-punk and Wilsey was fast developing a reputation as the enigmatic singer’s innovative foil. As much as Isaak’s wistful vocals, it’s Wilsey’s haunting guitar runs that define 1990 smash single “Wicked Game.”

Goldberg lost track of Wilsey soon after “Wicked Game” became a top-10 hit. The writer moved on from the San Francisco market to more auspicious gigs. After several years as a senior writer for Rolling Stone, Goldberg founded the pioneering Addicted To Noise online music zine in 1994. He was also a senior vice president at SonicNet. Goldberg’s mission to document Wilsey’s extended fall from grace began in 2018, when he learned of the guitarist’s death at 61, his body shutting down after decades of chronic drug use. Wicked Game: The True Story Of Guitarist James Calvin Wilsey (HoZac) is Goldberg’s fifth book—and it may be the nearest and dearest to his heart. He explains why.

How did your relationship with Jimmy Wilsey begin?

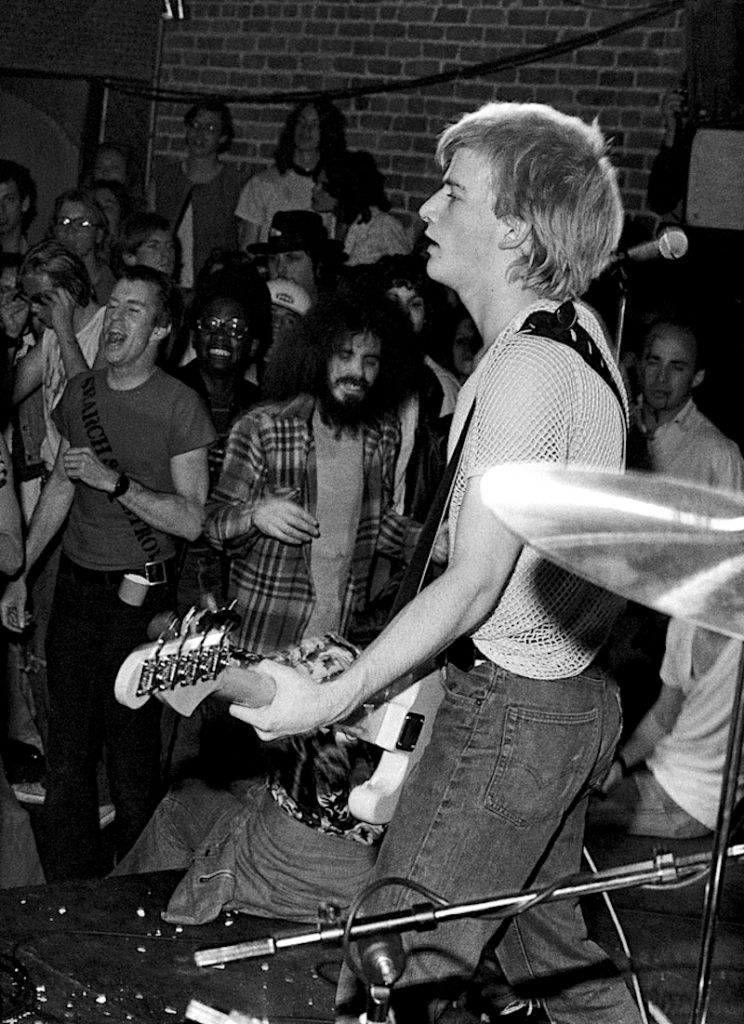

I met him in 1982, when I was doing a story for the San Francisco Examiner about up-and-coming bands in the Bay Area. A lot of people were talking about Silvertone, and I’d heard a demo that included the song “Blue Hotel.” I went to Berkeley Square to see them, and it was just a great set. Afterwards, I met Erik Jacobsen, who’d produced the Lovin’ Spoonful (and went on to produce all of Chris Isaak’s ’80s and ’90s albums). I’d been a huge fan of Lovin’ Spoonful when I was teenager in the ’60s, so I was well aware of Erik. He took me backstage, and that’s when I met Jimmy, Chris and the other guys in the band for the first time. Over the next eight or nine years, I wrote a lot of stories about them.

When did you and Jimmy get close?

In 1991, I did a story for Rolling Stone on Chris. I went L.A., where I ended up hanging out with Jimmy. Later that year, I did a profile on him for Guitar Player. We became friends, and I’d go over to his place and hang out. Then he started getting flaky and stopped answering the phone. I didn’t know what was going on. Sometimes, I’d drive over there and knock on his door, and he wouldn’t answer. At certain point, it was too much. I had other things in my life.

How did you learn about his death?

I read about it for the first time on Facebook on Christmas Day—that he’d died the previous afternoon. I was shocked. Then I waited for the obit to show up in the San Francisco Chronicle. He was in two important bands in the Bay Area, including the Avengers, a significant band in the punk scene. He was responsible in a big way for “Wicked Game” becoming a hit. That’s something Chris told me. When I didn’t see anything in the Chronicle, the Los Angeles Times or Billboard, I called someone I know at Rolling Stone and said, “Hey, let’s do a story on Jimmy Wilsey.” They went for it.

Why the book?

There was so much more to the story. He was a very underrated guitar player. He was basically responsible for the mood of the first three Chris Isaak albums. He deserved to be remembered. It was something I was driven to do, and as I got into it, there were multiple things going on. I felt it should be a cautionary tale for musicians about what can happen. There were aspects of the San Francisco punk scene that needed to be told. And as I delved into it, I discovered things about Chris Isaak’s story that had never been told.

What made Jimmy such a unique guitarist?

There was a tone he had. There was a subtlety—an atmosphere he created and this feeling that came through. Scotty Moore, Duane Eddy, Link Wray—he drew on all those people. But the sound he got was his own. At times, there’s a real sadness conveyed. Other times, there’s just anger. I describe his playing as “barbed wire” at one point in the book. I also quote Lenny Kaye, and he said he felt like Jimmy was a guitarist’s guitar player. He wasn’t showy—he enhanced the song and the singer. He talks about the intro to “Wicked Game” as just this beautiful entrée into Chris Isaak’s vocal performance.

There are a lot of reasons why people succumb to drug addiction. Why do you think Jimmy couldn’t see his way out?

In Jimmy’s case, I believe it started with two things. For one, his family moved around quite a bit when he was very young—and that’s been identified as one factor that can lead someone to become an addict. They make friends, and they’re gone. They can’t count on things. Jimmy was also diagnosed with clinical depression that began when he was a kid. He was self-medicating. Jimmy told a friend that the first time his smoked heroin, he felt like he was going home. Apparently, it was just such a relief from the internal pain he felt. I don’t think he ever really wanted to stop using.

How did Jimmy feel about his worth as a musician?

I think he was confident about his playing. He made this very beautiful and moody solo album in 2007 called El Dorado in his dining room on his laptop. He used this thing called a B-Bender that was invented by Clarence White (and Gene Parsons) of the Byrds. It’s this spring system on the back of a Telecaster that allows you to create a pedal-steel sound while you’re playing the guitar. Lakeshore Records put out Jimmy’s solo album, and he said to one of the guys there, “People are going to hear [the B-Bender] and not know what it is.” He was proud of that. He was proud of his abilities on the guitar. He tried to come across as humble. But in reality, I don’t think he really was that humble.

—Hobart Rowland