The way the stars aligned for Tiny Tim’s success in 1968 was nothing short of stunning. His rise was one of the most circuitous, unlikely and sudden in the history of show business. But, even aside from his bizarreness and inexplicable tendency toward self-destruction, Tiny Tim’s was a kind of fame that would have been impossible for anyone to sustain. 55 years after its release, Richard Barone tiptoes around the making of Tiny Tim’s trouble-plagued 2nd Album.

Tiny Tim was born Herbert Khuary in Washington Heights, N.Y., on April 12, 1932. Growing up with an obsessive, encyclopedic knowledge of recordings from the “acoustical era” (1878 through the 1930s) and inspired by the crooners of that period, he dropped out of school and focused on becoming a performer, emulating his heroes while developing one of the most peculiar images and voices that show business had yet produced.

Tiny went through a litany of stage names, including Larry Love and Darry Dover, before settling on “Tiny Tim”—a shortened version of his then-most-recent moniker Sir Timothy Tims. Through it all, he perfected his vocal and performance skills and refined his singular persona. He was excessively polite and mannered, with long flowing hair, a fluttering falsetto and a flaming, campy effeminacy. Far from being tiny, at more than six feet tall, playing his diminutive ukulele that he pulled out of an ever-present shopping bag overflowing with old-timey sheet music, and wearing white face makeup, it’s a sure bet he earned some glaring glances on the 1950s New York City subways. Until his big break in 1967, Tiny would live in Washington Heights with his parents—his father Butros, who was Lebanese and the son of a Maronite Catholic priest, and mother Tillie, who was Polish- Jewish and the daughter of a rabbi. They were, by all accounts, distant, dismissive, unsupportive and downright embarrassed of their son’s appearance, peculiar affectations and musical ambitions.

As the early ’60s rolled around, Tiny made the rounds, performing regularly at Hubert’s Museum and Live Flea Circus, a Coney Island–style freak show in Times Square, where he was billed as the “Human Canary.” Next stop: Greenwich Village, which happened to be in the middle of spearheading a musical and cultural renaissance. Tiny found his way down to West Third Street, where he was booked at the Café Bizarre, then across the street at the Third Side, then down the block at the Café Wha?, where, according to Bob Dylan in Chronicles, Volume One, he and Tiny scrounged meals in the venue’s kitchen during Fred Neil’s afternoon sets. “Tiny Tim and I would go in the kitchen and hang around,” wrote Dylan. “Norbert the cook would usually have a hamburger waiting.”

That was followed by a stint with the Living Theater on 14th Street, where Dylan and girlfriend Suze Rotolo went to see Tiny perform. “It made no difference to him if he was being ridiculed or appreciated,” wrote Suze Rotolo in her excellent memoir, A Freewheelin’ Time. “He never stepped out of character.” The Living Theater is also where Tiny met avant-garde filmmaker and Warhol associate Jonas Mekas. “Tiny would stand up in the audience before a performance and spontaneously break into a song,” Mekas once recalled to me, after proclaiming to me that he was Tiny’s first “agent.”

Soon after the Living Theater appearances, Tiny was favorably reviewed in the New York Times, featured in the Village Voice, made some outlandish appearances in a couple of experimental indie films and was the subject of recordings made by Mekas and others. Tiny was making a name for himself in the underground New York City arts/nightclub scene.

With his reputation growing, Tiny continued to make the rounds of the Village clubs. It was during this time that Tiny also performed with embattled comedian, social critic and satirist Lenny Bruce, who became a devoted friend and fan. Tiny was booked at the Fat Black Pussycat, then finally found a home at the Page Three, a popular gay bar on Seventh Avenue and West 10th Street. There, he was fully in his element: singing for—and fantasizing over—the lesbian women he adored. “I was so thrilled to be in their company,” he told me when we met a decade and a half later. “I was one of the few men [giggles] that they allowed to their parties.”

Tiny was complex. And yet, for all of his eccentricities, he seemed to connect with some of the most important musical heroes of the era. “I was hanging out with him on the stoop one day, up near Washington Heights,” the legendary Dion DiMucci told me on a phone call. “The conversation was that he didn’t eat cheese. He said he ate it one night, and his heart started to beat real quick. It raced. So he didn’t eat cheese, especially at night. He was a weird character! He was going downtown, to the (South Street) Seaport, to a produce market down there to buy a stalk of bananas. Then, he’d get on the subway with that entire stalk of bananas.”

It would have been quite a stretch to think such an admittedly freaky dude could ever be a mainstream success. Nonetheless, it was at Steve Paul’s The Scene—where Jimi Hendrix would hang out and where the Doors and Blues Project performed—that Tiny was approached by Warner Bros./Reprise Records visionary Mo Ostin, who, after witnessing a sparsely attended but rousing set, signed Tiny to Frank Sinatra’s Reprise label in August 1967. Tiny’s bizarreness did not faze Ostin, who would also sign the Fugs, Captain Beefheart and, later, the Sex Pistols. In fact, it was Tiny’s very uniqueness that interested Ostin. Whether Sinatra himself was a fan is doubtful. But, Frank’s daughter, Nancy Sinatra, was charmed. “I liked Tim very much,” Nancy messaged me as I was writing this. “He was a kind man with a good heart. We had fun together.”

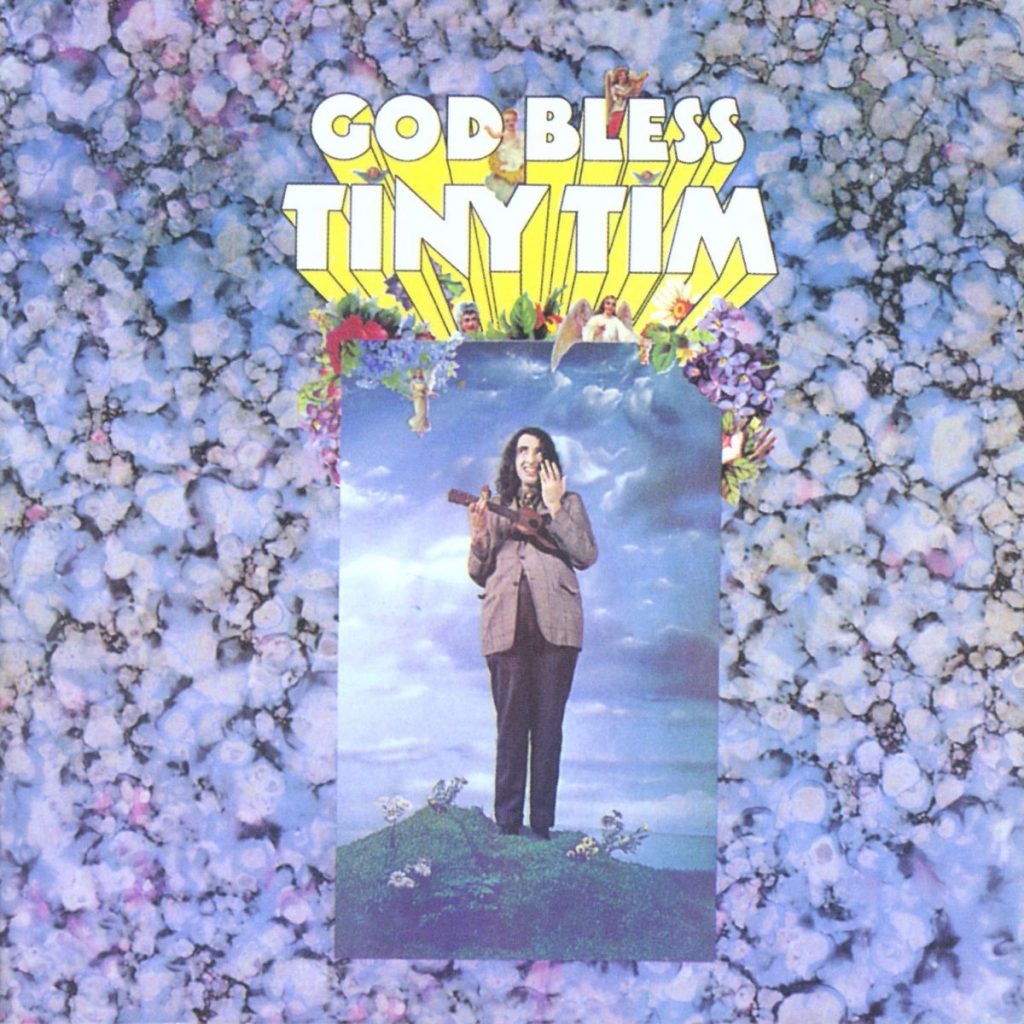

Producer Richard Perry was chosen to helm Tiny’s debut album for Reprise, God Bless Tiny Tim, a beautifully performed and orchestrated affair with flashes of the old, Tin Pan Alley music Tiny loved, fused with contemporary grooves, gender acrobatics (on his male/female duets with himself) and psychedelic embellishments—all buffed to a supreme pop polish. Not to mention, the album contained Tiny’s signature song, “Tip-Toe Thru’ The Tulips,” first made famous by Nick Lucas in 1929. Recalling the full-album experience of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album of several months prior, God Bless Tiny Tim provided a blueprint for Perry’s future, lushly arranged and eclectic productions for Harry Nilsson and Ringo Starr.

A series of appearances on NBC’s Laugh-In couldn’t have been better timed. It was 1968, the most tumultuous year of the decade. On January 22, Tiny Tim made his national television debut. Introduced as “the toast of Greenwich Village,” Tiny projected a kind of knowing innocence. Blowing kisses, singing in his most flamboyant falsetto, with his long curly hair and thrift-shop clothing, Tiny stood in stark contrast to short-haired, tuxedoed hosts Dan Rowan and Dick Martin. It’s easy to see how Tiny might have been embraced by hippies. “Tiny Tim seemed like some sort of flower child under the influence of Rudy Vallee,” wrote Mark Deming in AllMusic. The appearances on Laugh-In propelled Tiny to the upper reaches of the Billboard charts. On July 13, God Bless Tiny Tim peaked at number seven, right between Cream’s Disraeli Gears and Hendrix’s Are You Experienced?; “Tip-Toe” had peaked at number 17 a few weeks earlier. Overnight, Tiny Tim, at long last, was a star. So, now what?

Tiny Tim’s management was quick to get him out on the road to capitalize on his success. Before you know it, Tiny was one of the top-paid performers on the Las Vegas Strip, and by October 1968, he would be performing at the Royal Albert Hall in London. The dizzying rise changed everything and must have started to take a toll on Tiny, who now, behind the scenes, was often uncooperative and combative with his managers and producer Perry. With the debut album still on the charts, Reprise was intent on getting Tiny back into the recording studio to cut a follow-up as quickly as possible. And they did, though, unfortunately, it was not soon enough.

Before the second Reprise album could be released, a series of long-forgotten sessions that Tiny had recorded six years prior, in 1962 when he was Darry Dover, came back to haunt him as the unauthorized album With Love And Kisses From Tiny Tim: Concert In Fairyland. Packaged with a garish, psychedelic cover, it was thrust into the market by the low-budget Bouquet Records. Instead of Richard Perry’s careful production choices, meticulous arrangements by Artie Butler and the excellent Wrecking Crew musicianship heard on God Bless Tiny Tim, here the arrangements were two-dimensional and poorly recorded. On at least one song, the tape was even sped up to make Tiny’s voice sound higher in pitch. Besides the fact that the producers of the album saw fit to add annoying, canned audience applause—not to mention heckling, whistling and laughing—to the studio recordings and demos, Tiny himself had decided to sing some of the songs deliberately out of tune and camped-up others to the point of near-parody.

Justin Martell, author of Eternal Troubadour: The Improbable Life Of Tiny Tim, told me, “Tiny often gave conflicting answers and had inscrutable reasoning for some of his decisions, both personally and professionally. In the case of Concert In Fairyland, he gave two different answers: one, that he had sung off-key in order to ‘spite’ the album’s producers, and, two, that he had been hired to sing terribly as a gimmick to capitalize on a now-forgotten singer called ‘Max The Butcher’ who unironically made off-key recordings and died suddenly when his record got traction as a novelty hit. Either explanation seems entirely plausible. When faced with professional conflicts, especially if he felt he was being mocked, Tiny would cloak passive-aggressive retaliation against those who had upset him behind his projected image of naïveté.”

Notwithstanding a few mildly entertaining moments, Concert In Fairyland was, at the very least, an unwanted distraction that could rob sales from Tiny’s legitimate, Warner Bros. releases. Cease-and-desist orders against Bouquet Records were immediately issued by Warner Bros., but it was too late. The damage had been done. Would fans shell out their hard-earned cash again for the official release, Tiny Tim’s 2nd Album, when it would come out just a month or two later?

Justin Martell continues, “By the time they got around to recording Tiny Tim’s 2nd Album about six months after God Bless Tiny Tim (which was actually still on the Billboard 200 in fall ’68), a lot had happened: Two non-album singles, ‘Bring Back Those Rockabye Baby Days’ and ‘Hello Hello,’ had failed to gain traction on the charts, and Concert In Fairyland had sold 100,000 copies before the injunction had it pulled from circulation, drawing considerable ire from fans who had enjoyed God Bless. (In Tiny’s mind), it was everyone else’s fault; the engineers and Richard Perry had botched the production of the two singles, and Warner Bros. had been too cheap to pay the owners of the Fairyland tapes (one of whom was record exec George Golder, who just happened to be Richard Perry’s father in law) the $25,000 they demanded not to release them.”

When it was issued in November ’68, what fans got with Tiny Tim’s 2nd Album was ostensibly God Bless Tiny Tim Part 2: well-produced, lavish orchestrations, a tight rhythm section and old-timey tunes all edited together into a seamless whole. This time, however, something was missing. Having insisted on more control in the studio and perhaps as a reaction to his over-the-top performances on Concert In Fairyland, Tiny played it straight. Gone were the psychedelic embellishments and contemporary sounds, and gone were the gloriously giddy giggles. Instead, Tiny went for the “professional,” all-round entertainer approach. What was sacrificed was the sustained, unabashed exuberance of God Bless Tiny Tim.

Here, on 2nd Album, Tiny retreats—in his own, signature way, of course—to traditional song stylings. In Tiny’s hands, even contemporary songs like “She’s Just Laughing At Me,” written by the Addrisi Brothers and first recorded in 1967 by the Collage, sound decades old. (Note: Interestingly, that song was also covered by Harry Nilsson, three years before he would also be produced by Richard Perry.) On “She’s Just Laughing At Me,” Tiny sings, “Girls never gave me half a chance, I never got a second glance … Could it be that I have the right to think that she really likes what she sees, or is she just laughing at me?” in a superbly sensitive performance that sounds positively confessional. Oddly, Tom Paxton’s earnest “Can’t Help But Wonder Where I’m Bound” gets one of the goofiest treatments, sung almost entirely in falsetto with particularly comic scatting.

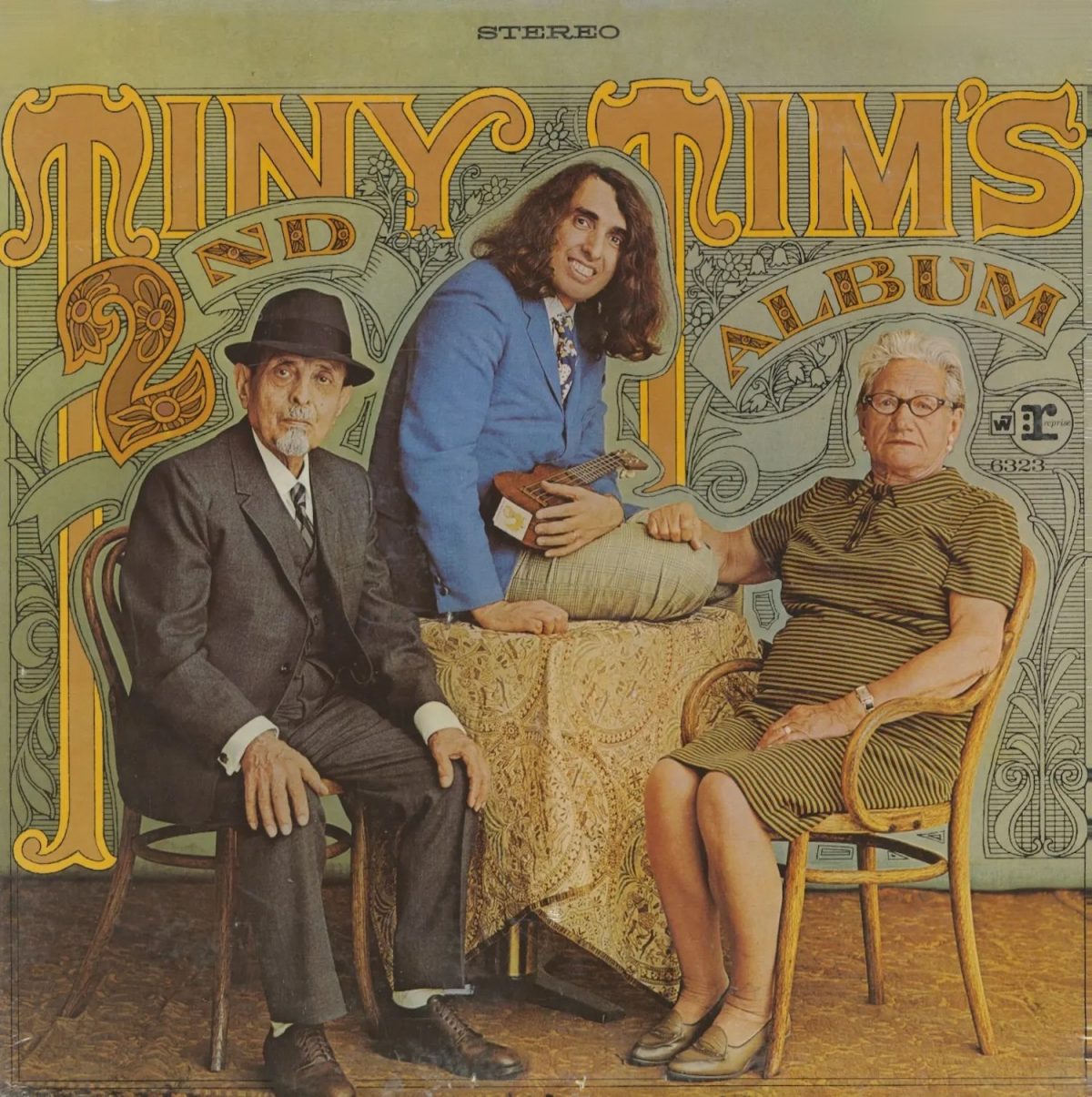

For reasons known only to Tiny, he seemed now to be playing more to the parents of his young fans, instead of to the kids themselves. He barely threw a bone to the hippies who adored him just a few months prior. And, speaking of parents, let’s talk about the cover. As if to alienate teenagers completely and to simultaneously spite and embarrass his own elderly parents, he put them on the front cover of the album. Yes, there they are, Butros and Tillie, looking none too happy, seated at an antique-looking table with a background of faded, sickly green walls. Their baby boy, the son they barely tolerated, now 36, is seated on the table between them, smiling broadly. Did anyone at the Warner Bros. art department tell Tiny or his manager that this cover might turn off some of his fans?

According to Martell, the cover photo was shot at CBS Studios on Broadway, later known as the Ed Sullivan Theater, on the occasion of Tiny’s first appearance on the Sullivan show. The show he had pledged to his unbelieving father that he would one day see his son on. Regardless of the reasoning, the cover was far from compelling, and more importantly, it lacked the magical troubadour image that God Bless Tiny Tim had conveyed so memorably. As the icing on the cake, to make sure his point was made, Tiny verbally, sardonically, thanks his parents for “standing behind him every step of the way on that rocky road to success,” right there on the album itself.

Whatever disappointments aside, there were still a good measure of magical moments on 2nd Album, and it is far from a creative failure. The dreamlike opening, “Come To The Ball,” sets the stage and harkens back to God Bless opener “Welcome To My Dream.” And the closing montage of “I’m Glad I’m A Boy”/“My Hero”/“As Time Goes By” is outrageously cinematic. I can think of no other artist who could have pulled it off. The kind of drama that is captured in the grooves could only have been performed by someone with the deep eccentricities and obsessions of Tiny Tim. For “As Time Goes By,” Tiny sings the rarely used intro verse (“This day and age we’re living in/Gives cause for apprehension/With speed and new invention/And things like third dimension”) that serves as a kind of mission statement, explaining his reasoning for looking to the past. While listening now, I couldn’t help but think of Bryan Ferry’s 1999 rendition of the same song and how Ferry’s fluttering vibrato reminds me of Tiny’s. Ferry may have toned it down a notch, but his heart is firmly in Tiny’s “golden age of Hollywood” realm. Did Ferry ever listen to 2nd Album? If you’re reading this, Bryan, please DM me.

A surprising highlight of 2nd Album is Jerry Lee Lewis’s 1957 hit “Great Balls Of Fire.” Arranged by Richard Perry, this track breaks out of the ’30s and ’40s balladeering and gives Tiny the opportunity to rock. Even Jerry Lee himself was impressed. “I don’t know who that cat is, but he can sure do it,” he told Tiny’s A&R rep Bruce Bissell. He’s right, of course. The track rocks hard and true.

Says Martell, “While the album is certainly true to how Tiny viewed his artistry and features ‘Great Balls Of Fire,’ which Tiny felt was his ‘best recording’ for Reprise, Tiny Tim’s 2nd Album feels like a retreat to a more conservative musical approach and a new-but-befuddling artistic direction. With God Bless, Tiny Tim and his team had released an album that held its own amongst those by Tiny’s contemporaries, but with Tiny Tim’s 2nd Album, he proved too inflexible and lacked the vision to continue on the cutting edge.”

Tiny Tim’s 2nd Album failed to crack the Billboard 200. But, regardless of any shortcomings (real or perceived) or its lack of chart action, it is the work of a true artist, dangerously committed to his desires and true to his own vision. Tiny went to his grave convinced that Concert In Fairyland crushed the chances of 2nd Album, spoiled his relationship with Warner Bros. and derailed his career forever. Producer Perry is in agreement. To others, it can be seen as just another nasty speed bump on “that rocky road to success.” To be fair, sophomore releases—especially ones that follow a massively successful debut—are famously challenging. Every artist knows that public perception is everything in an entertainment career. How Tiny Tim wanted to be perceived is just as much a mystery now as it was then.

Not long after 2nd Album, on a promotional tour for his book of poetry, Beautiful Thoughts, Tiny met, courted and married Miss Vicki—a spectacle that was conducted on The Tonight Show With Johnny Carson and viewed by an estimated 40 million people. It provided another wave of fame and notoriety for Tiny Tim that made him a household name. But all the tabloid headlines in the world couldn’t get him another hit record. He tried. Oh, how he tried.

When I first met and worked with Tiny, he was performing in a minuscule, sparsely attended roadside TraveLodge motel bar in the outskirts of Tampa. His superstardom seemed at the time to be in the very distant past. But, in reality, it was only six years after he had played to his largest audience, an estimated 600,000 people, at the Isle Of Wight Festival in England. Tiny knew from own experience how fleeting fame can be. But even then, and until his passing 20 years later, in 1996, while performing “Tip-Toe Thru’ The Tulips” for the very last time, he was always looking for that followup hit.

In Tampa, we talked and played music all through the night in his room. As his stories unfolded, I had to ask how it felt—those days at the end of the 1960s when he was on top of the world. “It was … won-der-ful!” he would say, seeming just as happy in the present.

© Richard Barone

From the forthcoming book The White Label Promo Preservation Society, Volume 2 (HoZac Books, 2023).

Richard Barone recorded and produced Tiny Tim’s album Rare Moments Vol. 1: I’ve Never Seen A Straight Banana, at age 16. Barone’s latest book, Music + Revolution: Greenwich Village In The 1960s (Backbeat Books, 2022), includes many details of Tiny Tim’s time in the Village. Barone also appears in the documentary Tiny Tim: King For A Day (2020).

Thanks to Justin Martell, Nancy Sinatra and Dion DiMucci.