When he’s on not on the road playing drums with the War On Drugs, Charlie Hall confesses to being a bit of a homebody. As such, he wishes he knew more about the music scene in his adopted hometown of Philadelphia. There was a time when he had reasonably informed opinions about local acts, but the wheels of success have a way of creating distance between artists and the scenes that fostered them. For Hall, that reality is frustrating and a little embarrassing.

“I wish I was a little more plugged in than I am,” he says. “I feel bad because I get asked. But I do think there’s a lot of cool shit happening here—most of which I have no idea about.”

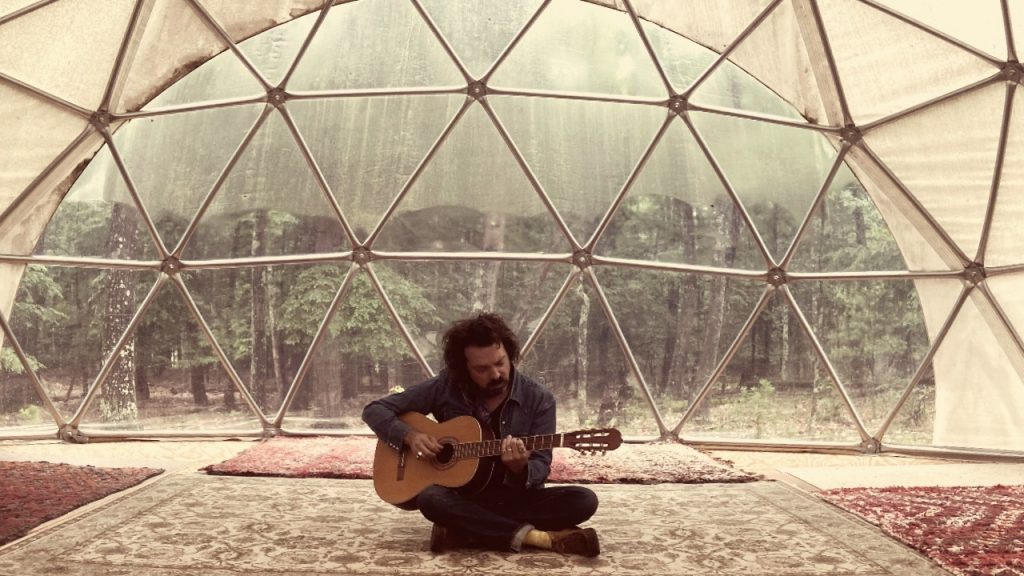

While Hall’s status as a long-standing member of one of the bigger acts in rock may be his most high-profile gig, it certainly doesn’t define him. The multi-instrumentalist, producer, composer and songwriter has backed Tommy Guerrero, Windsor For The Derby, Jens Lekman and others. He also produced last year’s A Philly Special Christmas album, which made some noise on the Billboard charts. And he’s just released his solo debut, Invisible Ink, on co-producer Quinn Lamont Luke’s El Triángulo Records.

Invisible Ink’s nine mostly instrumental tracks are expansive, multi-textured, cinematic and oddly soothing. The album features global contributions from a host of friends, including Chicago’s James Elkington (Tweedy, Steve Gunn), Richmond, Va.’s Brian Jones (Slang, Agents Of Good Roots), Montreal’s Andrew Barr (Barr Brothers, Feist) and Norway-based Chris Walla (Death Cab For Cutie), along with the War On Drugs’ Dave Hartley, Robbie Bennett and Eliza Hardy Jones.

We caught Hall in a nostalgic mood at home in Philadelphia, where he was busy plotting his next move and anticipating the not-so-far-off day when he’ll be back behind the kit for the next War On Drugs album.

How did you find your way to Philadelphia?

I grew up in Connecticut basically, then college in Virginia, where I met my wife. We moved San Francisco and were there for our 20s. I knew about Philadelphia because my brother moved here in the mid-’90s. When I’d come to visit him, I always felt really at home. I was on tour in Japan with Tommy Guerrero when I first moved here. My wife was the catalyst for it. The dotcom thing was crazy; we were two schoolteachers and musicians. She was just like, “This is no way to live the rest of our lives.” If it wasn’t for her, I’d still be sitting in San Francisco eating a burrito.

So you met (Philly scenester) Joey Sweeney through Craigslist. I’m sure that opened a can of worms.

I met fuckin’ Sweeney, who was looking for a drummer. Then I met (late MAGNET senior writer Jonathan) Valania and (former MAGNET writer) Gabe Boylan. Adam (Granduciel) and I moved here at the same time. I met him when he was playing with the Capitol Years. Then he started to put together the Drugs, and he was writing with Kurt (Vile). It was this beautiful thing—everyone was playing in each other’s bands, going to each other’s gigs and propping each other up. I was like, “Man, this place is great.”

Now you get to tour the world with the Drugs.

I have the best job on the planet. I get to play with the best bass player in the universe—getting to lock in with Dave (Hartley). I mean, the whole band is a rhythm section really. It’s the most fun thing imaginable. To have the chance to convey this music to people around the world … being part of that transmission—that’s the thing.

You talk about this overwhelming sense of community you felt in Philly. In some ways, Invisible Ink emulates that. It’s this massive collaboration with people from all over the place.

Yeah, I guess so. I didn’t set out to make something that sounded a certain way. It all started out as kind of challenge—or a threat [laughs]—from Quinn. He said, “You’re coming to my studio in New York. I don’t care of this is a ‘you’ thing. I don’t care if this is a ‘me and you’ thing. I don’t care if this is a ‘me’ thing. You’ve been making records with other people for 25 years. I want to hear what your music sounds like.” I said to myself, “I’m not even sure I want to know my music sounds like.” I went up there sort of sheepishly, without tunes. But I did go up there with all my favorite instruments. And I did go up there with fragments of ideas.

It’s interesting how you approached to the song titles.

Each song is connected to a time in my life—like when I first discovered that open tuning or I first got into minor ninth chords. I just followed the trail, and it was a really solitary exercise at first. But then a friend here or there would ask to hear what I was working on, and they’d be like, “Hey, would it be cool if I put some pedal steel on this?” And be like, “Fuck yeah, it would be cool.” And then it comes back, and it’s like in 3D. That’s how it happened. It was an exercise in generosity and love.

—Hobart Rowland